Computational Modeling of Endometrial Dynamics: From Digital Twins to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of computational modeling of the endometrium, a critical frontier in women's health research.

Computational Modeling of Endometrial Dynamics: From Digital Twins to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of computational modeling of the endometrium, a critical frontier in women's health research. We explore the foundational mathematical principles, from phenomenological models capturing hormonal regulation to sophisticated quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) frameworks. The review details the application of diverse methodologies, including machine learning for diagnostic prediction, spatial eco-structural models of the tumor microenvironment, and agent-based simulations. We critically examine the challenges of model validation and optimization, highlighting the synergistic role of 3D organoids as biological validation platforms and the use of AI for refining model parameters. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of model types—from fractional calculus for capturing treatment memory effects to optimal control theory for designing personalized therapy regimens. This synthesis is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage computational power to decode endometrial biology, accelerate therapeutic discovery, and pave the way for personalized medicine in conditions like endometriosis, endometrial cancer, and infertility.

Decoding the Endometrium: Foundational Principles and Mathematical Frameworks

Biological Foundations of Endometrial Dynamics

The human endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus, exhibits remarkable regenerative capacity, undergoing more than 400 cycles of growth, differentiation, and shedding throughout a woman's reproductive life [1]. This dynamic tissue is exquisitely responsive to systemic hormonal cues, primarily 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4), which orchestrate precise morphological and physiological changes across the menstrual cycle [2]. The endometrium consists of two distinct layers: the stratum functionalis (functional layer) that undergoes cyclic changes and is shed during menstruation, and the stratum basalis (basal layer) that remains and facilitates regeneration [1] [2].

Endometrial regeneration involves complex interactions between multiple cell types, including luminal and glandular epithelial cells, stromal cells, vascular endothelium, and immune cells, all embedded within a dynamically remodeling extracellular matrix (ECM) [1]. Recent 3D imaging has revealed that endometrial glands in the basalis layer form a unique rhizome-like network that expands horizontally along the myometrium, with glands vertically emanating into the functionalis layer [1]. This sophisticated architecture supports the endometrium's exceptional regenerative capability, characterized by repeated shedding and subsequent regeneration without scarring [3].

The menstrual cycle progresses through three distinct phases driven by hormonal fluctuations:

- Menstrual phase: Shedding of the functionalis layer when no embryo implants

- Proliferative phase: Estrogen-driven regeneration and growth of the functionalis

- Secretory phase: Progesterone-mediated differentiation to support embryo implantation [2]

These cyclic transformations make the endometrium one of the most dynamically regenerative tissues in the human body, yet this complexity also renders it susceptible to various pathologies when regulatory mechanisms fail.

Endometrial Pathologies and Clinical Challenges

Dysregulation of endometrial dynamics underlies several prevalent diseases that affect millions of women worldwide, often with limited treatment options. The major endometrial pathologies include:

Table 1: Major Endometrial Pathologies and Their Characteristics

| Disease | Key Pathological Feature | Clinical Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Asherman Syndrome | Intrauterine adhesions and scarring following endometrial damage [1] | Infertility, menstrual disturbances, poor response to hormone therapy [4] |

| Thin Endometrium | Inadequate endometrial growth with thickness typically <7mm [4] | Failed embryo implantation, low success rates in assisted reproduction [4] |

| Endometriosis | Presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity [1] | Chronic pain, infertility, inflammation, and altered hormone response [1] |

| Adenomyosis | Endometrial tissue misplaced within the myometrium [1] | Heavy menstrual bleeding, pain, and altered hormone response [1] |

| Endometrial Cancer | Malignant proliferation of endometrial cells, often linked to hormonal imbalances [1] | Hyperproliferation, progression from endometrial hyperplasia [1] |

The etiology of thin endometrium exemplifies the multifactorial nature of endometrial disorders, with proposed causes including Asherman's syndrome, previous intrauterine surgery, pelvic radiation, genetic factors, impaired uterine blood flow, infections, certain medications, and dysfunctional estrogen signaling [4]. A recent single-cell RNA sequencing study further suggested that cellular senescence in stroma and epithelium combined with collagen overdeposition around blood vessels contributes to endometrial thinness [4].

Conventional treatments for endometrial disorders, including hormonal therapies, growth factors, and vasoactive substances, have demonstrated limited and inconsistent efficacy [4]. This therapeutic challenge underscores the critical need for more sophisticated research models that can accurately capture endometrial complexity and enable the development of more effective interventions.

Experimental Models for Studying Endometrial Dynamics

Traditional Research Models and Their Limitations

Endometrial research has historically relied on various model systems, each with distinct advantages and limitations for studying tissue dynamics:

Table 2: Comparison of Endometrial Research Models

| Model System | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Models (rodents, primates) [1] | Replicate entire lesion with all cell types; enable study of regeneration and systemic effects [1] | Costly; significant physiological variations between species; cannot exactly reproduce human disease [1] |

| Tissue Explants [1] | Preserve 3D tissue structure; retain all native cell types and physical interactions [1] | Reduced viability after 24 hours; limited ability to manipulate specific cell types [1] |

| 2D Cell Cultures [1] | Simple, inexpensive; enable high-throughput compound testing [1] | Cannot reproduce tissue architecture or cell-ECM interactions; lack physiological relevance [1] |

| Co-culture Models [1] | Include multiple cell types; study paracrine or direct cell interactions [1] | Do not necessarily replicate tissue structure; extended culture difficult [1] |

While these traditional approaches have yielded valuable insights, their limitations have impeded progress in understanding endometrial disease mechanisms and developing effective treatments. The field has particularly struggled with models that adequately recapitulate the dynamic hormonal responses, complex cell-cell interactions, and 3D tissue architecture characteristic of human endometrium.

Advanced Bioengineering Approaches

Recent advances in bioengineering have generated more sophisticated models that better mimic the endometrial microenvironment:

Endometrial Organoids: These 3D self-organizing structures derived from primary endometrial cells replicate key aspects of endometrial physiology, including epithelial cell polarity, hormone responsiveness, and gene expression profiles of eutopic and ectopic endometrium [1]. They can be established from menstrual flow non-invasively and are amenable to long-term expansion, biobanking, and drug testing [1] [3]. However, current endometriosis organoids typically contain only one cell type and do not fully reproduce interactions between endometrial cells and their microenvironment [1].

Microfluidic Systems: These platforms enable precise control over the cellular microenvironment and can replicate uterine peristaltic movement through controlled fluid flow and shear stresses [1]. They allow for the integration of multiple cell types and environmental factors, though current systems often lack circulation of culture medium and may be limited to endometrial cells only [1].

Bioengineered Scaffolds: Natural and synthetic hydrogel-based scaffolds simulate the physical and biomechanical properties of the native endometrium, maintaining the survival of transplanted stem cells and facilitating endometrial repair [3]. These materials show promise for supporting endometrial regeneration and improving reproductive outcomes.

Computational Modeling Approaches

Mathematical Modeling of Menstrual Cycle Dynamics

Phenomenological-based mathematical models represent a powerful approach for simulating the dynamic changes in endometrial tissue throughout the menstrual cycle. These models connect physiological phenomena with quantitative accuracy, allowing researchers to simulate multiple menstrual cycles and test hypotheses about regulatory mechanisms [2].

A recently developed phenomenological-based model predicts volume changes in the functional layer of the endometrium across menstrual cycle phases by considering changes in endometrial tissue, blood flow through spiral arteries, shedding of endometrial cells, and menstrual blood flow [2]. The model uses estrogen and progesterone dynamics as input variables, with hormone levels taken from a pre-existing validated model [2]. Key aspects of this modeling approach include:

- Tissue Dynamics: Modeling the growth and regression of endometrial tissue in response to hormonal signals

- Vascular Changes: Simulating the development and regression of spiral arteries that supply the functionalis layer

- Shedding Mechanisms: Representing the process of tissue breakdown and menstruation

- Feedback Loops: Incorporating regulatory interactions between hormones, tissue growth, and vascular development

This model successfully simulated endometrial volume and thickness changes that align with experimental data from the literature, providing valuable insights into the interactions between ovarian hormones and endometrial dynamics [2].

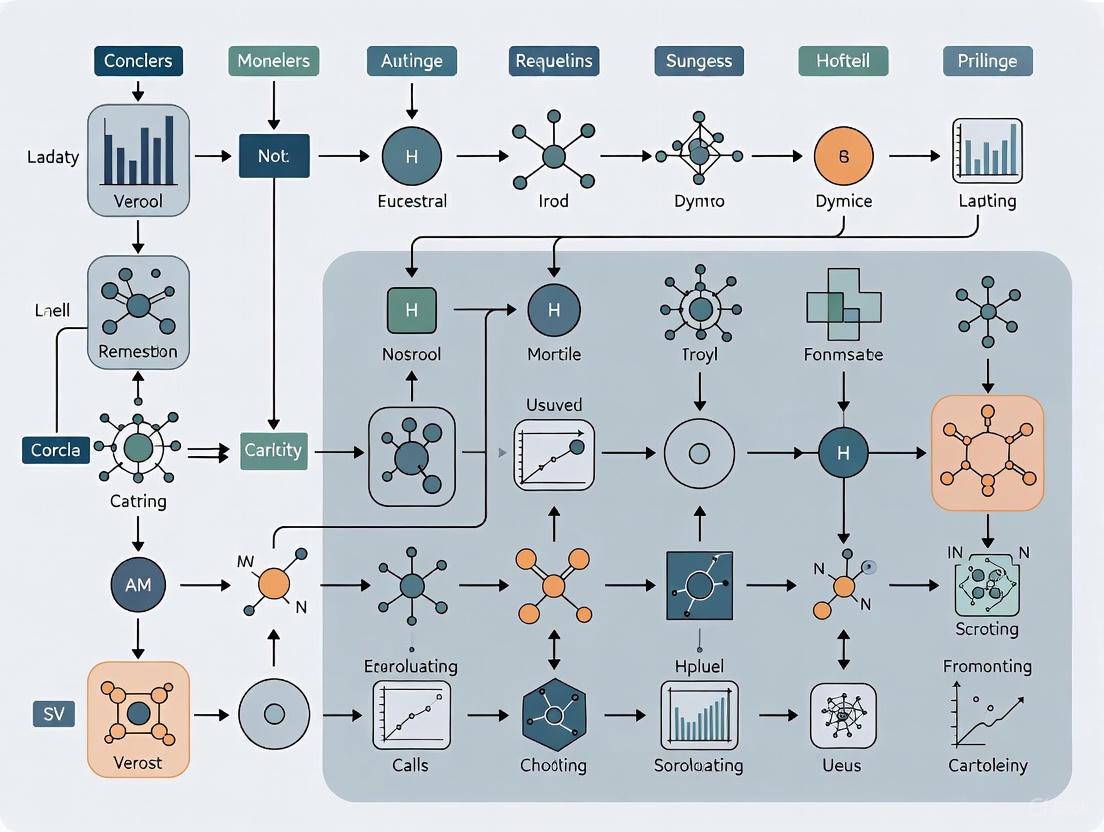

Diagram Title: Menstrual Cycle Computational Model Structure

Comparative Analysis of Computational Modeling Algorithms

In other domains of biological research, comparative studies of computational modeling algorithms have demonstrated the importance of selecting appropriate methods for specific research questions. A recent study comparing protein or peptide modeling algorithms revealed that different approaches have complementary strengths depending on the properties of the target molecule [5].

For hydrophobic peptides, AlphaFold and Threading approaches complemented each other, while for hydrophilic peptides, PEP-FOLD and Homology Modeling showed complementary strengths [5]. PEP-FOLD provided both compact structures and stable dynamics for most peptides, while AlphaFold generated compact structures for most targets [5]. These findings highlight that an integrated approach combining multiple algorithms may yield superior results compared to relying on a single method—a principle that likely applies to endometrial modeling as well.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as particularly valuable for studying structural stability and intramolecular interactions over time. In the peptide modeling study, researchers performed 40 simulations (100 ns each) to determine the stability of structures predicted by different algorithms [5]. Similar approaches could be adapted to study the dynamics of endometrial proteins and signaling molecules involved in menstrual cycle regulation.

Experimental Protocols for Endometrial Research

Protocol: Establishing and Maintaining Endometrial Organoids

Purpose: To create 3D in vitro models that closely mimic endometrial architecture and function for disease modeling and drug testing [1].

Materials:

- Human endometrial tissue samples or menstrual flow collection

- Advanced DMEM/F-12 culture medium

- Essential growth factors (EGF, Noggin, R-spondin)

- Matrigel or other ECM scaffold

- Hormone supplements (estradiol, progesterone)

- Digestion enzymes (collagenase, dispase)

Procedure:

- Tissue Processing: Mechanically mince endometrial tissue samples and digest with collagenase/dispase solution (2 mg/mL) at 37°C for 60-90 minutes [1].

- Cell Isolation: Sequential filtration through 100μm and 40μm strainers to isolate epithelial fragments. Centrifuge at 800×g for 5 minutes.

- Matrix Embedding: Resuspend cell pellets in ice-cold Matrigel and plate as droplets in pre-warmed culture plates. Polymerize at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Organoid Culture: Overlay with complete culture medium containing required growth factors and hormones. Culture at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Medium Refreshment: Change culture medium every 2-3 days, monitoring organoid formation and growth.

- Passaging: For maintenance, dissociate organoids with TrypLE every 7-14 days and replate in fresh Matrigel.

Applications: Disease modeling, drug screening, host-pathogen interaction studies, and personalized medicine approaches [1].

Protocol: Implementing a Phenomenological-Based Mathematical Model

Purpose: To develop a dynamic model predicting endometrial volume changes during the menstrual cycle in response to ovarian hormones [2].

Materials:

- Computational environment (MATLAB, Python, or similar)

- Experimental data for validation (endometrial volume/thickness measurements)

- Hormonal concentration data (estrogen, progesterone)

- Parameter estimation algorithms

Procedure:

- System Definition: Identify key system components—endometrial tissue volume, spiral artery length, menstrual blood flow [2].

- Equation Formulation: Develop differential equations representing growth, regression, and shedding processes based on physiological principles.

- Parameter Estimation: Use literature data and optimization algorithms to estimate model parameters that minimize difference between simulations and experimental data [2].

- Hormonal Inputs: Integrate pre-validated models of estrogen and progesterone dynamics as system inputs [2].

- Model Validation: Compare simulation outputs with independent experimental data for endometrial volume, thickness, and menstrual blood flow [2].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify parameters with greatest influence on system behavior to guide future experimental measurements.

Applications: Testing hypotheses about regulatory mechanisms, predicting pathological conditions, and simulating interventional strategies [2].

Research Reagent Solutions for Endometrial Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Endometrial Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media [1] | Advanced DMEM/F-12, organoid culture media | Support growth and maintenance of endometrial cells and organoids |

| Growth Factors [1] [4] | EGF, Noggin, R-spondin, G-CSF | Promote cell proliferation and differentiation in 2D and 3D culture systems |

| Enzymatic Dissociation [1] | Collagenase, Dispase, TrypLE | Tissue processing and organoid passaging |

| Extracellular Matrices [1] [3] | Matrigel, synthetic hydrogels, HA-based scaffolds | Provide 3D support structure for organoids and tissue engineering |

| Hormonal Supplements [1] [2] | 17β-estradiol, progesterone, selective receptor modulators | Study hormone response and mimic menstrual cycle phases |

| Stem Cell Markers [4] | CD133+, mesenchymal stem cell markers | Isolation and characterization of regenerative cell populations |

| Computational Tools [5] [2] | MATLAB, Python, molecular dynamics software | Implement mathematical models and analyze complex datasets |

Diagram Title: Integrated Endometrial Research Workflow

Future Perspectives and Integrative Approaches

The future of endometrial research lies in developing increasingly sophisticated integrated approaches that combine advanced experimental models with computational methods. Organoid technology, microfluidic systems, and bioengineered scaffolds continue to evolve toward more faithfully recapitulating the native endometrial microenvironment [1] [3]. Similarly, computational models are incorporating more biological detail, including immune cell interactions, spatial organization, and multi-scale regulatory networks.

Emerging therapeutic strategies for endometrial disorders highlight the potential of these integrated approaches. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy, rich in growth factors and cytokines, has shown promise in improving endometrial thickness and receptivity in clinical studies, though standardized protocols are still needed [4]. Stem cell therapies using bone-marrow-derived stem cells (BMDSCs) and adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) have demonstrated ability to restore endometrial function and improve reproductive outcomes in pilot trials [4]. These interventions represent a new frontier in treating conditions like thin endometrium and Asherman's syndrome that have historically proven challenging to manage.

Computational modeling will play an increasingly critical role in optimizing these therapies by predicting treatment outcomes, personalizing intervention strategies, and reducing the need for extensive trial-and-error experimentation. As mathematical models incorporate more biological complexity and are validated against data from advanced experimental systems, they will accelerate the translation of basic research findings into clinical applications, ultimately improving diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for endometrial disorders.

The human endometrium exhibits a remarkable capacity for cyclical regeneration, undergoing monthly phases of growth, differentiation, and shedding in response to ovarian hormone fluctuations. Phenomenological-based modeling has emerged as a powerful computational framework for simulating these dynamic processes by integrating mathematical formalism with physiological understanding. Unlike purely data-driven approaches, phenomenological models maintain a direct connection to underlying biological mechanisms while achieving quantitative accuracy in predicting system behavior [2]. This approach enables researchers to move beyond statistical correlations to capture the causal relationships governing endometrial dynamics.

Within the broader context of computational modeling of endometrial dynamics, phenomenological-based models fill a critical niche between overly simplistic statistical regressions and prohibitively complex mechanistic descriptions. They incorporate key physiological phenomena—including hormonal regulation, tissue growth, vascular changes, and menstrual shedding—into a mathematically tractable framework that can be validated against experimental data [2]. This balance of biological interpretability and computational efficiency makes these models particularly valuable for both basic research and pharmaceutical development, allowing researchers to simulate intervention outcomes and generate testable hypotheses about endometrial function and dysfunction.

Biological Foundation: Endometrial Dynamics and Hormonal Regulation

Endometrial Compartments and Menstrual Cycle Phases

The endometrium consists of two primary layers: the stratum basalis (basal layer) and stratum functionalis (functional layer). The basalis remains relatively stable throughout the menstrual cycle, providing progenitor cells for monthly regeneration. In contrast, the functionalis—comprising approximately two-thirds of the endometrial thickness—undergoes dramatic cyclic changes in response to ovarian hormones [2]. This compartmentalization is fundamental to menstrual function, as the functional layer is selectively shed during menstruation while the basal layer is preserved to support subsequent regeneration [6].

The endometrial cycle progresses through three distinct phases regulated by systemic concentrations of 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4):

- Proliferative Phase: Characterized by estrogen-driven regeneration and growth of the functional layer following menstruation.

- Secretory Phase: Initiated after ovulation, marked by progesterone-induced differentiation and vascular development to support potential implantation.

- Menstrual Phase: Triggered by progesterone withdrawal in the absence of pregnancy, involving tissue breakdown and shedding of the functionalis [2].

Hormonal Regulation and Key Physiological Processes

Ovarian sex steroids directly regulate endometrial transformations through receptor-mediated signaling pathways. Estrogen promotes endometrial proliferation and growth, while progesterone induces secretory differentiation and stabilizes the endometrium. The precise coordination of these hormonal signals ensures proper timing of endometrial receptivity and, in the absence of pregnancy, controlled tissue breakdown [2].

Critical processes incorporated into phenomenological models include:

- Endometrial Tissue Dynamics: Volume changes in the functional layer across cycle phases.

- Vascular Changes: Blood flow modulation through spiral arteries and associated angiogenesis.

- Menstrual Shedding: Controlled breakdown and removal of endometrial tissue.

- Cellular Turnover: Balance between proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [2].

Table 1: Key Hormonal Regulators of Endometrial Dynamics

| Hormone | Primary Source | Major Endometrial Actions | Phase of Dominance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17β-Estradiol (E2) | Ovarian Follicles | Stimulates proliferation & growth | Proliferative Phase |

| Progesterone (P4) | Corpus Luteum | Promotes differentiation & secretory activity | Secretory Phase |

| Gonadotropins (FSH/LH) | Anterior Pituitary | Regulate ovarian steroid production | Throughout Cycle |

Model Development: Mathematical Framework and Implementation

Core Mathematical Structure and State Variables

Phenomenological-based models of endometrial dynamics employ ordinary differential equations to describe the temporal evolution of key state variables in response to hormonal inputs. The core model structure typically tracks multiple interacting components:

- Functional Layer Volume (V_f): Represents the changing volume of the endometrial functionalis throughout the menstrual cycle.

- Spiral Artery Length (L_s): Captures the development and regression of the endometrial vasculature.

- Menstrual Blood Flow (F_m): Quantifies the extent of menstrual fluid loss during shedding.

- Hormonal Inputs (E2, P4): Model inputs derived from validated endocrine models of the ovarian cycle [2].

The general mathematical formulation follows a phenomenological-based semi-physical modeling approach, where differential equations are derived from understanding the underlying physiological phenomena rather than purely first principles or empirical fitting. This ensures parameters maintain biological interpretability while achieving quantitative accuracy [2].

Model Equations and Parameter Estimation

The system dynamics are described through coupled differential equations that capture the dominant phenomena governing endometrial behavior. For the functional layer volume, the rate of change can be expressed as:

dVf/dt = kg·f(E2) - kd·g(P4withdrawal) - ks·h(inflammatoryfactors)

Where:

- k_g represents the growth rate constant stimulated by estrogen

- k_d denotes the degradation rate following progesterone withdrawal

- k_s captures the shedding rate during menstruation

- f, g, h are phenomenological functions describing hormonal and inflammatory effects

Parameter estimation utilizes experimental data from multiple sources, including:

- Endometrial volume and thickness measurements from medical imaging

- Menstrual blood loss quantification

- Histological dating of endometrial biopsies

- Hormone concentration profiles from serum assays [2]

Table 2: Key Parameters in Endometrial Phenomenological Models

| Parameter | Biological Interpretation | Estimation Method | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| k_g | Estrogen-driven growth rate constant | Fit to proliferative phase volume data | 0.1-0.3 dayâ»Â¹ |

| k_d | Progesterone withdrawal degradation constant | Fit to secretory phase regression | 0.05-0.15 dayâ»Â¹ |

| k_s | Menstrual shedding rate constant | Fit to menstrual blood flow measurements | 0.2-0.5 dayâ»Â¹ |

| Ï„ | Hormonal effect time delay | Estimated from histologic dating | 1-3 days |

| E2â‚…â‚€ | Estrogen half-saturation constant | Derived from receptor binding studies | 50-150 pg/mL |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Endometrial Tissue Collection and Processing

Purpose: To obtain quantitative data on endometrial cellular composition and structure for model parameterization and validation.

Materials Required:

- Endometrial biopsy catheter or curette

- Transport medium (Advanced DMEM/F12 with antibiotics)

- Collagenase IV or Liberase digestion enzymes

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Tissue culture plates with Matrigel matrix

- Organoid culture medium supplements (B27, N2, growth factors) [7] [8]

Procedure:

- Obtain endometrial biopsies from consenting participants at specific cycle phases (confirmed by LH surge dating or histology).

- Immediately place tissue samples in cold transport medium and process within 2 hours.

- Mechanically mince tissue followed by enzymatic digestion at 37°C for 60-90 minutes.

- Filter through 100μm strainers to isolate epithelial glands from stromal components.

- Embed digested tissue in Matrigel droplets and overlay with organoid culture medium.

- Culture organoids for 7-14 days, monitoring structural development and hormonal responses [8].

- Analyze organoid morphology, hormone receptor expression, and response to hormonal manipulations.

Validation Metrics:

- Epithelial-to-stromal ratio quantification across cycle phases

- Hormone receptor expression patterns (ER-α, PR)

- Response to estradiol and progesterone exposure

- Secretory product analysis (glycodelin, MMPs) [9] [8]

Hormonal Manipulation and Menstruation Induction Protocol

Purpose: To experimentally validate model predictions regarding hormonal control of menstrual shedding using murine models.

Materials Required:

- Transgenic mouse models with chemogenetic actuators

- Clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) or other chemogenetic ligands

- Hormone pellets (estradiol, progesterone)

- Tissue fixation and processing reagents

- Single-cell RNA sequencing reagents [6]

Procedure:

- Implement hormonal priming in transgenic mice using estradiol and progesterone pellets over 21 days.

- Induce progesterone withdrawal through pellet removal to simulate luteal regression.

- Activate premenstrual differentiation pathways using chemogenetic tools (CNO administration).

- Monitor tissue responses through timed tissue collection at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours post-induction.

- Process tissues for histology, immunohistochemistry, and single-cell spatial transcriptomics.

- Quantify extent of shedding, immune cell infiltration, and vascular changes.

- Compare transcriptional profiles to human endometrial data to validate model relevance [6].

Validation Metrics:

- Percentage of endometrial area shed

- Spatial patterns of fibroblast differentiation

- Immune cell recruitment dynamics

- Vascular permeability and breakdown

- Correlation with human menstrual transcriptomes

Applications in Reproductive Medicine and Drug Development

Modeling Endometrial Responses to Pharmaceutical Interventions

Phenomenological models provide valuable platforms for simulating endometrial responses to therapeutic agents, including hormonal contraceptives, selective receptor modulators, and novel targeted therapies. By incorporating drug-specific parameters (receptor binding affinity, pharmacokinetic profiles, dose-response relationships), these models can predict:

- Endometrial thickness changes during treatment cycles

- Breakthrough bleeding incidence and patterns

- Impact on menstrual cycle regularity

- Tissue-specific versus systemic effects [2] [10]

For endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and endometriosis, customized model variants can incorporate pathological features including androgen sensitivity, inflammatory signaling, and progesterone resistance. This allows in silico testing of treatment strategies before clinical implementation [11] [10].

Integration with Advanced Experimental Systems

The combination of phenomenological modeling with emerging experimental platforms creates powerful synergies for basic research and translational applications:

Organoid Co-culture Systems: Endometrial organoids replicate glandular physiology and hormonal responsiveness in three-dimensional culture. When integrated with computational models, they provide quantitative data on epithelial-stromal interactions, hormone response dynamics, and pharmacological perturbations. Recent advances enable organoid derivation from various patient populations, including those with infertility, endometriosis, or endometrial cancer, facilitating personalized medicine approaches [7] [8].

Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Histology: Deep learning algorithms can automatically segment endometrial tissue compartments, quantifying epithelial and stromal areas with accuracy exceeding 92%. This high-throughput quantification provides robust data for model parameterization and validation across normal and pathological conditions [9].

Figure 1: Iterative Framework for Model Development and Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Endometrial Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organoid Culture Components | Matrigel, B27 supplement, N2 supplement, Noggin, R-spondin-1 | 3D modeling of endometrial gland physiology | [7] [8] |

| Growth Factors & Cytokines | FGF10, HGF, EGF, A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor) | Maintenance and differentiation of endometrial epithelia | [7] [8] |

| Hormonal Reagents | 17β-estradiol, progesterone, RU486 (mifepristone) | Manipulation of endocrine signaling pathways | [2] [6] |

| Molecular Analysis Tools | Single-cell RNA sequencing reagents, spatial transcriptomics platforms | Characterization of cellular heterogeneity and differentiation states | [6] |

| Computational Tools | MATLAB with ode45/fde12 solvers, Python with SciPy, R with deSolve | Numerical simulation of differential equation models | [2] [12] |

Figure 2: Core Hormonal Signaling Pathways Regulating Endometrial Dynamics

Future Directions and Implementation Considerations

The continued development of phenomenological-based models for endometrial dynamics will benefit from integration with emerging technologies and computational approaches. Promising directions include:

Multi-scale Model Integration: Linking endometrial tissue-level models with cellular-level processes (receptor signaling, gene regulation) and organ-level interactions (hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis) will create more comprehensive representations of reproductive physiology. Reduced-order modeling techniques can help manage complexity while maintaining predictive capability [11].

Personalized Medicine Applications: Incorporating patient-specific parameters (hormone profiles, endometrial thickness measurements, genetic variants) can generate individualized model predictions for clinical decision support in infertility treatment and menstrual disorder management.

Advanced Computational Frameworks: Fractional calculus approaches using Caputo derivatives can capture memory effects and non-local interactions in biological systems, potentially improving representation of hysteresis in hormonal responses [12]. Optimal control theory frameworks can leverage these models to design personalized treatment protocols that optimize therapeutic outcomes while minimizing side effects [12].

Figure 3: Personalized Medicine Pipeline Using Endometrial Models

For researchers implementing these approaches, we recommend beginning with established model frameworks [2] and adapting them to specific research questions through iterative refinement with experimental data. The protocols and resources outlined herein provide a foundation for generating quantitative validation datasets, while the computational tools enable simulation of endometrial dynamics under various physiological and experimental conditions.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis is a central regulatory system that controls reproductive function through complex hormonal interactions. Computational modeling of this axis provides a powerful framework for integrating multi-scale biological data, from gene expression to systemic hormone dynamics, to understand both normal reproductive physiology and pathological states. Within endometrial dynamics research, these models are invaluable for investigating disorders such as endometriosis and infertility, and for simulating the effects of pharmacological interventions. The integration of transcriptomic data with mathematical modeling allows researchers to move beyond associative observations to construct mechanistic, predictive models of HPO axis function [13] [14].

Key Quantitative Data from HPO Axis Transcriptomics

Transcriptomic analyses across HPO axis tissues have revealed dynamic gene expression patterns throughout developmental stages and in response to physiological challenges. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in HPO Axis Tissues Across Developmental Stages [13]

| Tissue | Comparison (Weeks) | Number of DEGs | Key Biological Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamus | 15w vs 20w vs 30w vs 68w | 381 | Tissue development, regulation of reproductive hormone biosynthesis |

| Pituitary | 15w vs 20w vs 30w vs 68w | 622 | Regulation of reproductive hormone secretion |

| Ovary | 15w vs 20w vs 30w vs 68w | 1,090 | Ovarian development and function |

| Ovary | 30w vs 15w | 867 | High ovulation capacity-related processes |

Table 2: Hormone and Follicle Changes in Response to Energy Availability [15]

| Parameter | Control Group | Energy-Deprived Group | Re-fed Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg laying rate | Baseline | Significantly decreased | Recovered |

| Ovarian index | Baseline | Significantly decreased | Recovered |

| Small yellow follicles (SYF) | Baseline | Significantly decreased | Recovered |

| Normal hierarchical follicles (NHIE) | Baseline | Significantly decreased | Recovered |

| Estradiol (Eâ‚‚) | Baseline | Decreased | Recovered |

| Luteinizing hormone (LH) | Baseline | Decreased | Recovered |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) | Baseline | Increased (contrasting pattern) | Returned to baseline |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: HPO Axis Transcriptomic Profiling and Analysis

Purpose: To characterize gene expression patterns across hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian tissues at different developmental stages or experimental conditions.

Materials:

- Hy-line brown laying hens (15, 20, 30, and 68 weeks of age) or equivalent model organism

- Trizol RNA extraction reagent

- Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform or equivalent sequencing system

- Primer Script RT reagent Kit for qRT-PCR validation

- Nano Photometer spectrophotometer, Qubit RNA Assay Kit, Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system

Procedure:

- Tissue Collection: Euthanize subjects and immediately extract hypothalamus, pituitary, and ovarian tissues (excluding follicles >2mm diameter). Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C.

- RNA Isolation: Isolate total RNA using Trizol reagent. Assess RNA quality using spectrophotometry (Qubit Fluorometer) and integrity (Agilent Bioanalyzer).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare cDNA libraries and sequence using Illumina platform to generate 125bp paired-end reads.

- Quality Control: Process raw reads to remove adapters, poly-N sequences, and low-quality reads using Perl scripts. Calculate Q20, Q30, and GC content of clean data.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Calculate FPKMs using StringTie. Identify DEGs using edgeR package with thresholds of adjusted p < 0.05, |log fold change| ≥ 1, and FPKM > 1 in at least one group.

- Functional Annotation: Perform GO enrichment analysis using GOseq R package (p < 0.01) and KEGG pathway analysis using KOBAS software (p < 0.05).

- Network Analysis: Construct protein-protein interaction networks using STRING database (confidence score ≥ 0.7) and visualize with Cytoscape.

- Validation: Validate RNA-seq results using qRT-PCR with appropriate statistical analysis [13].

Protocol 2: Computational Modeling of HPO Axis Dynamics

Purpose: To develop mathematical models that simulate HPO axis hormone dynamics and their perturbation in pathological states or therapeutic interventions.

Materials:

- Transcriptomic datasets from HPO axis tissues

- Hormone measurement data (Eâ‚‚, Pâ‚„, LH, FSH, GnRH)

- Mathematical modeling software (MATLAB, R, Python with appropriate libraries)

- Clinical or experimental data for model validation

Procedure:

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate modeling framework based on research question:

Data Integration: Incorporate transcriptomic data on key regulatory genes (e.g., GnRHR, CGA, steroidogenic enzymes) and hormone measurements.

Model Parameterization: Estimate parameters using experimental data. For ion channel models, conduct sensitivity analysis to identify key parameters (e.g., K⺠current conductances and time constants) [16].

Model Implementation:

- Implement differential equations representing hormone synthesis, secretion, and feedback loops

- Incorporate spatial relationships (e.g., hypothalamus-pituitary-ovary communication)

- Include temporal dynamics (pulsatile secretion, menstrual cycle variations)

Model Validation: Compare model predictions with independent experimental data not used in parameter estimation.

Simulation Experiments: Use validated model to simulate:

Sensitivity Analysis: Identify key model parameters and potential intervention targets through global sensitivity analysis [16] [14].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

HPO Axis Regulatory Network

HPO Modeling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HPO Axis Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA from HPO tissues | Trizol RNA extraction reagent |

| Sequencing Platforms | Transcriptome profiling | Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Validation of RNA-seq results | Primer Script RT reagent Kit |

| Hormone Assay Kits | Quantification of reproductive hormones | Estradiol (Eâ‚‚), progesterone (Pâ‚„), LH, FSH assays |

| Cell Culture Systems | In vitro models of HPO axis components | Primary pituitary cells, ovarian granulosa cells |

| Mathematical Software | Computational modeling and simulation | MATLAB, R, Python with specialized libraries |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Analysis of transcriptomic data | edgeR, GOseq, KOBAS, STRING database |

| Visualization Tools | Network and pathway visualization | Cytoscape, Graphviz |

| Niridazole | Niridazole, CAS:61-57-4, MF:C6H6N4O3S, MW:214.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pongamol | Pongamol HPLC|CAS 484-33-3|Research Chemical |

Key Regulatory Genes and Ion Channels in HPO Function

Analysis of HPO axis transcriptomes has identified critical genes and signaling components that enable computational modeling of axis dynamics:

Steroidogenic Pathway Genes: PGR, HSD3B2, CYP17A1, CYP11A1, CYP21A2, STS, and CYP19A1 represent core components of steroid hormone biosynthesis identified through PPI network analysis [13].

Novel Regulatory Factors: ROCK2, TBP, GTF2H2, GTF2B, DHCR24, DHCR7, FDFT1, LSS, SQLE, MSMO1, CYP51A1, and PANK3 represent newly identified regulatory genes that expand our understanding of HPO axis control mechanisms [13].

Ion Channels in Uterine Excitability: KCNQ and hERG potassium channels contribute to the malleability of uterine action potentials, enabling the transition between plateau-like and long-lasting bursting-type APs as critical for parturition timing [16].

Energy-Responsive Genes: Energy deprivation downregulates genes related to energy and appetite-regulated neurotransmitter receptors and neuropeptides in the hypothalamus, subsequently inhibiting GnRH secretion and downstream pituitary-ovarian function [15].

Applications in Endometrial Dynamics Research

Computational models of the HPO axis provide critical insights for endometrial dynamics research, particularly in understanding and treating endometriosis. Three primary modeling approaches have been employed:

Regression and Machine Learning Models: These data-driven approaches enable non-surgical diagnosis of endometriosis by identifying associations between patient symptoms, characteristics, and medical history with disease presence, though they lack mechanistic insight [14].

Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) Models: These mechanism-based models predict therapy delivery and effects on ovarian function, incorporating patient attributes, drug properties, and endogenous molecules that affect treatment response [14].

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Models: These comprehensive models incorporate detailed biological mechanisms, including synthesis, transport, and interactions between components throughout the HPO axis, enabling prediction of system-wide responses to hormonal therapies and other interventions [14].

The integration of HPO axis transcriptomics with these computational approaches provides a powerful framework for advancing our understanding of endometrial dynamics in both health and disease states.

Computational modeling has emerged as a powerful methodology for understanding the complex dynamics of endometrial tissues, which undergo vast changes each month during a person's reproductive years to prepare for potential pregnancy. Diseases of the endometrium, including endometriosis, adenomyosis, endometrial cancer, and Asherman syndrome, affect a significant portion of the population, yet efficient treatments remain limited due to the complexity of these conditions [1]. The endometrium consists of multiple cell types—including luminal epithelial cells, glandular epithelial cells, stromal cells, and immune cells—whose proportions and interactions change throughout the menstrual cycle in response to ovarian sex hormones [1]. This biological complexity necessitates sophisticated computational approaches that can capture spatial and temporal dynamics, cell-cell interactions, and hormonal regulation.

The field employs three primary computational frameworks—Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs), Partial Differential Equations (PDEs), and Agent-Based Models (ABMs)—each offering distinct advantages for different research questions. ODEs model system-wide changes over time, PDEs incorporate spatial dynamics, and ABMs simulate individual cell behaviors and interactions. These approaches are not mutually exclusive; hybrid models that combine elements from multiple frameworks often provide the most comprehensive insights into endometrial function and dysfunction. As research progresses, these computational methods are increasingly integrated with experimental data from novel model systems, including endometrial organoids and microfluidic devices, creating a more robust framework for understanding endometrial diseases and developing targeted therapies [1].

Theoretical Foundations of Computational Frameworks

Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs)

2.1.1 Fundamental Principles and Applications Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) are mathematical equations that describe the evolution of a system over time through functions of one independent variable and their derivatives. In the context of endometrial research, ODEs typically model population dynamics of different cell types or concentration changes of hormones and signaling molecules. These models are particularly valuable for capturing the temporal aspects of the menstrual cycle, where hormone levels (estrogen, progesterone) fluctuate in a regular pattern, driving cellular changes in the endometrial tissue [14]. The core strength of ODE modeling lies in its ability to provide a system-level perspective on dynamics that are homogeneous across space, making it ideal for understanding overall trends and equilibrium states in biological systems.

ODE models in endometrial research often take the form of compartmental models, where different biological states (e.g., proliferative, secretory, menstrual phases) are represented as distinct compartments with transition rates between them. These models can incorporate the effects of hormonal therapies by modifying transition parameters or adding terms that represent drug interactions. For instance, pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) models use ODEs to predict how drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted in the body, and how they subsequently affect endometrial tissue [14]. This approach has been valuable for optimizing hormonal therapies for endometriosis and other estrogen-associated conditions while minimizing adverse events.

2.1.2 Mathematical Formulation A typical system of ODEs for modeling endometrial dynamics might take the form:

dx/dt = f(x, t, θ)

where x represents a vector of state variables (e.g., concentrations of hormones, numbers of specific cell types), t represents time, and θ represents parameters that govern the system dynamics (e.g., rate constants, production rates, degradation rates). For example, a simple model of estrogen (E) and progesterone (P) interactions might be represented as:

dE/dt = αE - βE · E - γEP · E · P dP/dt = αP - βP · P - γPE · P · E

where α terms represent production rates, β terms represent degradation rates, and γ terms represent interaction coefficients between the hormones.

Partial Differential Equations (PDEs)

2.2.1 Spatial Dynamics in Endometrial Modeling Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) extend the concept of ODEs by incorporating spatial dimensions, making them particularly valuable for modeling how endometrial properties vary not only over time but also across physical space. While ODEs assume well-mixed, homogeneous systems, PDEs can capture heterogeneities in cell distribution, nutrient gradients, and hormone diffusion that are characteristic of real endometrial tissue [17]. This spatial component is crucial for understanding phenomena such as the formation of endometrial lesions in endometriosis, the invasion of endometrial tissue into the myometrium in adenomyosis, and the spatial progression of endometrial cancer.

PDE models of endometrial dynamics typically involve reaction-diffusion equations, where "reaction" terms represent local interactions and transformations (similar to ODE terms), while "diffusion" terms represent the spatial movement or spreading of substances or cells. For instance, a PDE might model how inflammatory cytokines diffuse through endometrial tissue, creating spatial gradients that influence immune cell recruitment and activation. Similarly, PDEs can capture the spatial dynamics of angiogenesis—the formation of new blood vessels—which is critical for both normal endometrial regeneration and pathological processes in endometrial diseases [18].

2.2.2 Mathematical Framework A general reaction-diffusion equation for modeling spatial dynamics in the endometrium might take the form:

∂u/∂t = D · ∇²u + f(u, x, t)

where u(x,t) represents the concentration of a substance or density of cells at position x and time t, D is the diffusion coefficient, ∇² is the Laplace operator representing diffusion, and f(u,x,t) represents local reactions or interactions. For modeling multiple interacting species (e.g., different cell types, hormones, nutrients), a system of coupled PDEs would be used:

∂ui/∂t = Di · ∇²ui + fi(u1, u2, ..., u_n, x, t)

where i = 1,...,n for n different species.

Agent-Based Models (ABMs)

2.3.1 Individual-Based Modeling of Cellular Behavior Agent-Based Models (ABMs) represent a fundamentally different approach from equation-based models, focusing on the behaviors and interactions of individual entities (agents) rather than population-level averages. In the context of endometrial research, agents typically represent individual cells (epithelial cells, stromal cells, immune cells) or cellular components that collectively give rise to tissue-level phenomena [19]. Each agent follows a set of rules that dictate its behavior, such as proliferation, differentiation, migration, or death, often in response to local environmental cues or interactions with neighboring agents. This "bottom-up" approach is particularly powerful for capturing emergent phenomena—system-level behaviors that arise from numerous local interactions but cannot be easily predicted from individual agent rules alone.

ABMs are exceptionally well-suited for modeling the heterogeneity inherent in endometrial systems, where individual cells may have different genetic profiles, receptor expressions, or behavioral tendencies. For example, in endometriosis, ABMs can simulate how individual endometrial cells with varying capacities for invasion and survival might establish lesions in ectopic locations [1]. Similarly, ABMs can capture the complex feedback between different cell types in the endometrial microenvironment, such as the paracrine signaling between epithelial and stromal cells that is crucial for normal endometrial function and often disrupted in disease states.

2.3.2 Formal Agent-Based Modeling Structure A typical ABM for endometrial dynamics can be formally described by:

ABM = (A, E, R, S)

where:

- A = {a1, a2, ..., a_n} represents the set of agents (cells)

- E represents the environment (tissue structure, chemical gradients)

- R = {r1, r2, ..., r_m} represents the behavioral rules for agents

- S represents the scheduling scheme for agent activation

Each agent ai has a state si that might include its cell type, position, age, receptor expression, and other relevant attributes. The behavioral rules R determine how agents update their states based on their current state, the states of neighboring agents, and environmental conditions. For example, a simple rule for an endometrial stromal cell might be:

IF (estrogenlevel > threshold) AND (spaceavailable) THEN probabilityofdivision = 0.1 END IF

Comparative Analysis of Computational Frameworks

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of ODE, PDE, and ABM Frameworks

| Characteristic | ODE Models | PDE Models | Agent-Based Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representation Scale | Population-level, homogeneous | Population-level, spatially continuous | Individual-level, discrete |

| Spatial Resolution | None (well-mixed assumption) | Continuous space | Discrete space (lattice or continuous) |

| Mathematical Foundation | Systems of differential equations | Partial differential equations | Rule-based computational algorithms |

| Computational Demand | Generally low | Moderate to high | High to very high |

| Handling of Heterogeneity | Limited (requires population subdivisions) | Through continuous spatial variation | Natural handling of individual variation |

| Emergent Behavior Capture | Limited | Moderate through pattern formation | Strong (key feature of methodology) |

| Typical Applications in Endometrial Research | Hormone dynamics, pharmacokinetics | Tumor shape, invasion patterns, gradient formation | Cell-cell interactions, lesion formation, tissue organization |

| Data Requirements | Aggregate time-series data | Spatiotemporal data | Individual behavior and interaction data |

| Implementation Complexity | Low to moderate | Moderate to high | High (programming intensive) |

| Analytical Tractability | High (analytical solutions sometimes possible) | Moderate (analytical solutions rare) | Low (primarily computational) |

Table 2: Applications of Computational Frameworks to Specific Endometrial Diseases

| Endometrial Disease | ODE Applications | PDE Applications | ABM Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endometriosis | Hormone therapy response, inflammatory cytokine dynamics | Spatial spread of lesions, diffusion of inflammatory mediators | Cell migration and adhesion in ectopic sites, immune cell interactions |

| Adenomyosis | Hormonal regulation of invasion | Pattern of myometrial invasion | Epithelial-stromal interactions in invasion process |

| Endometrial Cancer | Tumor growth kinetics, drug pharmacodynamics | Tumor shape evolution, angiogenesis patterns | Heterogeneous cell populations, clonal evolution, drug resistance emergence |

| Asherman Syndrome | Regeneration dynamics post-injury | Spatial pattern of fibrosis | Stem cell recruitment and differentiation during repair |

The choice between ODE, PDE, and ABM frameworks depends heavily on the specific research question, available data, and computational resources. ODE models offer mathematical elegance and computational efficiency for system-level questions where spatial heterogeneity can be reasonably neglected. They are particularly valuable for modeling hormonal regulation throughout the menstrual cycle and predicting patient responses to hormonal therapies [14]. The formalized nature of ODEs makes them amenable to mathematical analysis techniques such as stability analysis and bifurcation theory, which can provide deep insights into system dynamics.

PDE models bridge the gap between ODEs and ABMs by incorporating spatial dynamics while maintaining a continuous mathematical framework. They are ideal for investigating phenomena where spatial patterns and gradients play crucial roles, such as the formation of endometrial tissue boundaries, the invasion of endometrial cells into adjacent tissues, and the spatial distribution of drug delivery [17]. However, PDEs become computationally challenging for complex geometries and multiple interacting species, often requiring sophisticated numerical methods for solution.

ABMs excel at capturing the heterogeneity, adaptive behaviors, and emergent phenomena that characterize complex biological systems like the endometrium. Their strength lies in representing individual cells with distinct properties and behaviors, allowing for natural modeling of cellular decision-making processes, cell-cell interactions, and the evolution of population heterogeneity [19] [20]. This makes ABMs particularly valuable for studying the initiation and progression of endometrial diseases, where the interactions between different cell types and microenvironments drive pathological processes. The primary limitations of ABMs are their computational demands—especially for large numbers of agents—and the challenge of deriving general analytical insights from computational simulations.

Integrated Protocols for Endometrial Research

Protocol 1: Developing an ODE Model for Menstrual Cycle Regulation

Objective: To create a quantitative ODE model that captures the hormonal interactions regulating the menstrual cycle and predict how perturbations in these interactions contribute to endometrial diseases.

Background: The menstrual cycle is governed by complex feedback interactions between hormones from the hypothalamus, pituitary, and ovaries, which in turn regulate the endometrial cycle. Dysregulation of this system underpins many endometrial disorders, making mathematical modeling a valuable tool for understanding both normal and pathological states [14].

Materials and Reagents:

- Hormone concentration data: Time-series measurements of LH, FSH, estrogen, and progesterone

- Parameter estimation software: Packages such as MONOLIX, NONMEM, or MATLAB's parameter estimation tools

- ODE solver: Computational software with numerical ODE solving capabilities (MATLAB, R, Python with SciPy)

- Validation data: Clinical outcomes or experimental data not used in model development

Procedure:

- System Definition and Schematic Development

- Identify key system components: hypothalamic (GnRH), pituitary (LH, FSH), ovarian (estrogen, progesterone), and endometrial response elements

- Develop a conceptual diagram of interactions, noting stimulatory and inhibitory relationships

- Define system boundaries and time scale (typically one complete menstrual cycle)

Mathematical Formulation

- Translate conceptual diagram into a system of ODEs

- For each hormone, create a differential equation with production and clearance terms

- Incorporate feedback interactions using Hill functions or other nonlinear terms

- Example equation for estrogen dynamics: dE/dt = kLH·LH·(1 - E/KE) - δE·E - kP·P·E

Parameter Estimation

- Compile experimental data for hormone levels throughout the cycle

- Use maximum likelihood estimation or Bayesian methods to estimate unknown parameters

- Perform identifiability analysis to determine which parameters can be reliably estimated from available data

Model Validation

- Compare model predictions to clinical observations not used in parameter estimation

- Test model's ability to predict responses to interventions (e.g., hormone administration)

- Assess qualitative behaviors (e.g., emergence of periodic oscillations)

Experimental Applications

- Simulate hormonal perturbations corresponding to specific endometrial diseases

- Predict outcomes of therapeutic interventions

- Identify potential therapeutic targets through sensitivity analysis

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If model fails to exhibit cyclical behavior, review feedback loop structure and parameter ranges

- If parameter estimates have high uncertainty, consider structural identifiability analysis and additional data requirements

- If model validation fails, reassess model structure rather than just adjusting parameters

Protocol 2: Implementing an ABM for Endometriosis Lesion Development

Objective: To develop an agent-based model that simulates the establishment and growth of endometrial lesions in ectopic locations, capturing key cellular behaviors and interactions.

Background: Endometriosis involves the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, with complex interactions between endometrial cells, immune cells, and the local microenvironment. ABMs are ideal for capturing the heterogeneity and spatial organization of these processes [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cellular behavior data: Measurements of endometrial cell migration, adhesion, proliferation, and apoptosis rates

- Interaction data: Information on paracrine signaling between endometrial, immune, and stromal cells

- ABM platform: Specialized software such as NetLogo, Repast, or custom code in Python/Java

- Visualization tools: Capabilities for visualizing agent distributions and behaviors over time

Procedure:

- Agent Definition and Classification

- Define agent types: endometrial epithelial cells, stromal cells, immune cells (macrophages, T-cells)

- Specify agent attributes: position, cell type, state (migratory/proliferative/apoptotic), receptor expression, secretion profiles

- Establish initial conditions: number and distribution of each agent type

Rule Specification

- Develop behavioral rules for each agent type based on experimental evidence

- Example rule for endometrial cell migration: IF (chemokinegradient > threshold) AND (notincontactwithstromalcells) THEN movetowardhigher_concentration END IF

- Implement rules for cell division, death, and differentiation

- Define rules for secretion of and response to signaling molecules

Environment Setup

- Create spatial environment representing peritoneal cavity or other ectopic site

- Initialize chemical fields for relevant signaling molecules (cytokines, growth factors)

- Set up boundary conditions and spatial constraints

Model Execution and Data Collection

- Implement scheduling algorithm for agent activation (synchronous vs. asynchronous)

- Run simulations for sufficient time to observe lesion development

- Collect quantitative data on lesion size, cellular composition, spatial organization

Model Validation and Analysis

- Compare simulation results with histological observations of endometriosis lesions

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify most influential parameters

- Test model predictions through targeted experiments

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If simulation results lack biological realism, review and refine agent behavioral rules

- If computational demands are excessive, consider implementing more efficient spatial data structures

- If results are overly sensitive to small parameter changes, examine parameter ranges and model stability

Protocol 3: Hybrid PDE-ABM Approach for Endometrial Cancer Invasion

Objective: To develop a hybrid model that combines PDEs for diffusive signaling molecules with ABMs for individual cancer cells, capturing both the biochemical microenvironment and cellular heterogeneity in endometrial cancer invasion.

Background: Endometrial cancer progression involves both the dynamics of individual cancer cells with heterogeneous properties and the spatial distribution of signaling molecules in the tumor microenvironment. A hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both modeling paradigms to capture these multi-scale processes [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cellular imaging data: Time-lapse microscopy of cancer cell migration and proliferation

- Biochemical assay data: Measurements of growth factor and cytokine diffusion and degradation

- Computational framework: Hybrid modeling environment such as Chaste, PhysiCell, or custom MATLAB/Python code

- High-performance computing resources: For computationally intensive multi-scale simulations

Procedure:

- Model Scope and Scale Definition

- Define the spatial domain (e.g., tissue section with tumor-normal boundary)

- Specify time scale relevant to invasion process (days to weeks)

- Identify key processes to model at each scale:

- Cellular scale: division, migration, death

- Molecular scale: growth factor diffusion, degradation, cellular uptake

PDE Component Implementation

- Formulate reaction-diffusion equations for key signaling molecules (e.g., EGF, TGF-β)

- Implement numerical solver for PDEs (finite difference or finite element method)

- Set initial conditions and boundary conditions for chemical fields

ABM Component Implementation

- Define cancer cell agents with attributes: position, cell cycle status, receptor expression

- Implement behavioral rules that depend on local chemical concentrations

- Example: probabilityofdivision = f([GF], oxygen_tension)

Coupling Methodology

- Establish how ABM agents influence PDE fields (e.g., cells consume nutrients, produce signals)

- Implement how PDE solutions influence agent behaviors (e.g., chemotaxis along gradients)

- Ensure temporal synchronization between ABM and PDE components

Simulation, Analysis, and Experimental Integration

- Execute coupled simulations with appropriate numerical parameters

- Quantify invasion metrics: invasion depth, tumor shape, spatial heterogeneity

- Compare predictions with experimental models of endometrial cancer invasion

- Use model to test hypothetical treatment strategies targeting specific pathways

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If numerical instabilities occur, check time step sizes and spatial discretization

- If coupling between scales produces unrealistic behaviors, verify consistency of units and parameter magnitudes

- If computational demands limit exploration, consider simplifying less critical model aspects while preserving core dynamics

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Endometrial Modeling

| Category | Specific Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use in Endometrial Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Models | Endometrial organoids | 3D in vitro culture systems that mimic endometrial architecture and function | Studying gland formation, hormone response, disease modeling [1] |

| Primary endometrial cells | Epithelial and stromal cells isolated from endometrial tissue | Investigating cell-type-specific behaviors in controlled environments | |

| Microfluidic systems | Devices for culturing cells under controlled fluid flow and mechanical stimuli | Modeling menstrual shedding, embryo implantation, drug transport [1] | |

| Computational Frameworks | AgentTorch | Framework for large-scale agent-based modeling | Creating population-scale simulations of endometrial disease spread [21] |

| Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) | Hybrid framework combining mechanistic models with machine learning | Enhancing traditional models with data-driven components for improved prediction [22] | |

| MATLAB, Python with SciPy | General-purpose platforms for numerical computation and ODE/PDE solving | Implementing custom models of endometrial dynamics | |

| Data Sources | Clinical hormone measurements | Time-series data on hormone levels throughout menstrual cycle | Parameterizing and validating ODE models of menstrual cycle regulation [14] |

| Histopathological images | Spatial data on tissue architecture and cellular distribution | Parameterizing and validating spatial models (PDEs, ABMs) | |

| 'Omics datasets | Transcriptomic, proteomic, and genomic data from endometrial samples | Informing model structure and parameter ranges based on molecular profiles |

Visualizing Computational Framework Integration

Computational Framework Integration

The diagram illustrates how different computational frameworks integrate to model endometrial biological systems. ODE, PDE, and ABM approaches each capture distinct aspects of endometrial dynamics, which can be combined in hybrid models to generate predictions and insights. These model outputs then undergo experimental validation, which in turn refines our understanding of the biological system and improves the computational models.

Framework Selection Workflow

This workflow diagram guides researchers in selecting appropriate computational frameworks based on their specific research questions. Temporal dynamics questions typically suit ODE approaches, spatial pattern questions align with PDE frameworks, cellular heterogeneity questions benefit from ABM approaches, and multi-scale questions often require hybrid methodologies. Example applications illustrate how each framework addresses specific endometrial research challenges.

The field of computational modeling in endometrial research is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends likely to shape future investigations. Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) represent a promising framework that combines mechanistic models with machine learning, offering a balance between interpretability and predictive power [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for leveraging the growing availability of large-scale endometrial datasets while maintaining connection to biological mechanisms. Similarly, multi-scale modeling approaches that integrate molecular, cellular, tissue, and organism-level processes will provide more comprehensive understanding of endometrial diseases across biological scales.

The integration of high-resolution experimental data with computational models is another critical direction. Advanced imaging techniques, single-cell omics technologies, and detailed temporal monitoring of endometrial responses are generating rich datasets that can inform and validate increasingly sophisticated models. For instance, organoid technology and microfluidic systems provide unprecedented opportunities for generating quantitative data on endometrial cell behaviors under controlled conditions [1]. These experimental advances enable the development of more biologically grounded computational models that can make accurate predictions about endometrial function and therapeutic responses.

In conclusion, ODE, PDE, and ABM frameworks each offer distinct strengths for investigating different aspects of endometrial dynamics. ODEs provide efficient modeling of temporal processes like hormonal regulation, PDEs capture essential spatial dynamics of tissue organization and invasion, and ABMs excel at representing cellular heterogeneity and emergent behaviors. The integration of these approaches into hybrid models, combined with high-quality experimental data and emerging computational techniques, promises to advance our understanding of endometrial biology and accelerate the development of improved diagnostics and therapies for endometrial diseases. As these computational approaches become more accessible and widely adopted, they will play an increasingly central role in endometrial research, ultimately contributing to better health outcomes for people affected by endometrial conditions.

The human endometrium represents a paradigm of dynamic tissue remodeling, undergoing approximately 400-500 cycles of growth, differentiation, and shedding throughout a woman's reproductive life [23]. This remarkable regenerative capacity, driven by estrogen and progesterone fluctuations, necessitates sophisticated research approaches that bridge molecular mechanisms with tissue-level phenomena. Computational modeling integrated with advanced experimental systems now enables researchers to decode the complex hormonal signaling, cellular hierarchy, and spatial relationships that govern endometrial function in both physiological and pathological contexts [23] [24].

The endometrial regenerative program is orchestrated by tissue-resident stem/progenitor cells, primarily located within the basalis layer [23]. These cells demonstrate self-renewal and multilineage differentiation capabilities that sustain epithelial and stromal homeostasis after menstruation, parturition, or injury. Emerging evidence indicates that dysregulation of these endometrial stem/progenitor cells contributes to various clinical disorders including menstrual abnormalities, infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, endometriosis, and endometrial cancer [23]. This application note outlines integrated computational and experimental protocols for investigating endometrial dynamics across biological scales, with particular emphasis on hormone-responsive mechanisms, cell-cell communication networks, and translational applications in reproductive medicine.

Computational Modeling of Endometrial Cell Population Dynamics

Theoretical Foundation and Model Specification

Computational models employing ordinary differential equations (ODEs) provide powerful tools for quantifying how endometrial epithelial and stromal cell populations respond to hormonal and cytokine stimuli. These models simulate temporal changes in cell proliferation and death rates based on specific microenvironmental conditions [24].

Protocol: ODE-Based Modeling of Hormone-Driven Cell Proliferation

- Objective: To simulate the dynamics of endometrial epithelial organoid size and stromal cell density in response to hormone and cytokine exposure.

- Model Inputs: Experimentally measured rates of epithelial organoid formation and stromal cell proliferation across multiple hormone/cytokine conditions.

- Model Calibration: Parameter estimation using previously published experimental datasets from 3D co-culture platforms containing primary human endometrial epithelial organoids and endometrial stromal cells.

- Implementation:

- Formulate ODEs describing population changes for each cell type

- Incorporate terms for hormone- and cytokine-dependent proliferation

- Include cell death/apoptosis terms influenced by microenvironmental factors

- Calibrate using experimental data from mono- and co-culture systems

- Validation: Compare simulated cell densities with experimental measurements across different donor samples and culture conditions.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Endometrial Cell Population Modeling

| Parameter | Description | Units | Estimation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ïmax | Maximum proliferation rate | dayâ»Â¹ | Curve fitting to experimental data |

| KH | Hormone concentration for half-maximal effect | nM | Dose-response experiments |

| δ | Basal cell death rate | dayâ»Â¹ | Time-course measurements |

| αi,j | Cell-cell interaction coefficient | - | Co-culture vs mono-culture comparison |

| D | Molecular diffusion coefficient | μm²/s | Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) |

Spatial Modeling of Molecular Diffusion

Beyond population-level dynamics, partial differential equation (PDE)-based models simulate the spatial distribution and diffusion of signaling molecules within 3D endometrial cultures, accounting for cellular uptake and degradation processes.

Protocol: PDE-Based Diffusion Modeling

- Objective: To simulate molecular gradient formation and spatial heterogeneity in 3D endometrial culture systems.

- Model Inputs: Cell density predictions from ODE models; physical dimensions of 3D culture system; molecular properties of cytokines/hormones.

- Implementation:

- Formulate diffusion equations with uptake terms proportional to local cell density

- Set boundary conditions reflecting culture system geometry

- Solve numerically using finite element methods

- Application: Identify culture conditions where molecular gradients may create heterogeneous microenvironments affecting experimental outcomes.

Computational modeling workflow integrating cell population and spatial diffusion models.

Experimental Systems for Model Validation

3D Endometrial Organoid Culture and Analysis

Three-dimensional organoid cultures replicate endometrial architecture and function more accurately than traditional 2D systems, providing essential experimental platforms for validating computational predictions [23] [7].

Protocol: Establishment of Endometrial Cancer Organoids in Peptide Hydrogels

- Objective: To generate patient-derived endometrial cancer organoids that retain key tumor characteristics for drug screening and disease modeling.

- Materials:

- RFC self-assembling peptide (Ac-Arg-Leu-Asp-Ile-Lys-Val-Glu-Phe-Cys-Arg-Leu-Asp-Ile-Lys-Val-Glu-Phe-Cys-CONHâ‚‚) at 10 mg/mL stock concentration

- Advanced DMEM/F12 culture medium

- Growth factor supplements (B27, N2, EGF, FGF10, FGF2, R-spondin 1, Noggin)

- Small molecule inhibitors (A83-01, SB202190, Y-27632)

- Primary endometrial cancer tissue or cell lines

- Methods:

- Prepare RFC hydrogel by mixing 0.6 mL of 10 mg/mL RFC stock with 0.4 mL PBS to achieve 6 mg/mL final concentration

- Allow mixture to stabilize for 5 minutes at room temperature

- Embed dissociated endometrial cells in hydrogel at appropriate density

- Overlay with complete endometrial organoid culture medium

- Culture at 37°C with 5% CO₂, refreshing medium every 2-3 days

- Passage organoids every 7-14 days based on growth rate

- Validation: Confirm retention of tumor characteristics including proliferative activity, gene expression profiles, and drug resistance patterns [7].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Endometrial Organoid Culture

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Medium | Advanced DMEM/F12 with HEPES and L-Glutamine | Nutrient support | Provides stable pH environment for 3D culture |

| Supplements | B27, N2, N-Acetylcysteine, Nicotinamide | Enhanced cell viability | Critical for stem cell maintenance |

| Growth Factors | EGF, FGF10, FGF2, R-spondin 1, Noggin | Proliferation and differentiation signaling | Concentrations must be optimized for endometrial tissue |

| Small Molecules | A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor), SB202190 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Pathway modulation | Y-27632 especially important during passaging |

| Scaffold Matrix | RFC self-assembling peptide | 3D structural support | Concentration affects mechanical properties |

Spatial Profiling of Endometrial Tumor Microenvironment

Understanding cellular spatial relationships within the endometrial tumor microenvironment enables more accurate computational model development and provides insights into disease mechanisms [25].

Protocol: Imaging Mass Cytometry for Spatial Eco-Structural Analysis

- Objective: To quantify frequency, spatial distribution, and intercellular crosstalk of immune and stromal cell populations in endometrial cancer specimens at single-cell resolution.

- Materials:

- Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) endometrial tissue sections (4 μm thickness)

- Metal-conjugated antibodies (MaxPar X8 Antibody Labelling Kit)

- Antibody panel targeting: lymphocytes (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45, CD20), epithelial cells (E-cadherin, pancytokeratin), myeloid cells (CD11c, CD163), endothelial cells (CD31), stromal cells, cytokines, and immune checkpoints