Decoding the Uncertain: A Comprehensive Guide to VUS Interpretation in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the challenge of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI).

Decoding the Uncertain: A Comprehensive Guide to VUS Interpretation in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the challenge of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI). It covers the foundational genetic landscape of POI, detailing the over 90 associated genes and the high prevalence of VUS findings. The content explores established and emerging methodologies for VUS interpretation, including ACMG/AMP guidelines, functional assays, and advanced computational tools. It addresses critical troubleshooting strategies to optimize classification and minimize clinical ambiguity, and finally, outlines rigorous frameworks for the clinical and functional validation of POI-associated VUS, emphasizing their potential in therapeutic target discovery.

The Genetic Landscape of POI and the Scale of the VUS Challenge

Defining POI and the Critical Role of Genetic Etiology

FAQs on POI and Genetic Research

1. What is Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) and how is it diagnosed?

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) is a clinical condition characterized by the loss of ovarian function before the age of 40 [1] [2]. It is diagnosed based on the following criteria, which align with guidelines from the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) [3] [4]:

- Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea for at least 4 months.

- Elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level (>25 IU/L) on two occasions, more than 4 weeks apart [5] [2].

It is crucial to exclude other causes, such as chromosomal abnormalities, autoimmune diseases, or iatrogenic causes like chemotherapy and radiation [1] [3]. POI is distinct from menopause because ovarian function can be intermittent, and spontaneous ovulation and pregnancy, though rare, are still possible [1] [6].

2. Why is understanding genetic etiology critical in POI research?

A genetic etiology is a major contributing factor in a significant proportion of POI cases. Understanding it is vital for several reasons:

- High Prevalence of Unknown Etiology: In approximately 90% of diagnosed spontaneous POI cases, the underlying cause is unknown [1] [7]. Genetic research aims to solve these idiopathic cases.

- Establishing a Molecular Diagnosis: Identifying a pathogenic variant provides a definitive diagnosis for patients and families, ending a long and uncertain diagnostic odyssey [3].

- Informing Clinical Management: A genetic diagnosis can help assess associated health risks (e.g., for Fragile X premutation or Turner syndrome), guide reproductive planning, and enable cascade testing for relatives [3] [8].

- Elucidating Pathogenic Mechanisms: Discovering novel genes and variants expands our understanding of the fundamental biological processes governing ovarian development and function, including gonadogenesis, meiosis, and folliculogenesis [3].

3. What is a Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) and how should it be interpreted?

A Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) is a genetic variant for which there is currently insufficient evidence to classify it as either pathogenic or benign [9] [8] [10]. Interpretation guidelines are as follows:

- Not Clinically Actionable: A VUS should not be used for clinical decision-making regarding patient management or reproductive choices [9] [8] [10]. Clinical decisions must be based on personal and family history.

- A Spectrum of Suspicion: The VUS category is heterogeneous. Variants can be subjectively categorized on a "temperature" scale from "ice cold" (more likely benign) to "hot" (more likely pathogenic) based on available evidence [9] [10].

- Dynamic Classification: The classification of a VUS can change over time as more evidence accumulates from population databases, functional studies, and published case reports [9] [8]. Most VUSs are eventually reclassified as benign [9].

4. What experimental approaches can help clarify the role of a VUS in POI?

When a VUS is identified in a candidate gene, several experimental strategies can be employed to gather additional evidence:

- Family Segregation Studies: Testing parents and other affected or unaffected family members to see if the variant co-segregates with the disease phenotype. A de novo (new) variant in an affected child or inheritance from an affected parent can support pathogenicity [9] [8] [10].

- Functional Studies (In Vitro or In Vivo): Performing experiments to assess the biological impact of the variant on protein function, such as enzyme activity, protein expression, or subcellular localization. Providing functional evidence (PS3 code per ACMG guidelines) is a powerful method to upgrade a VUS to "Likely Pathogenic" [3] [8].

- Review of Updated Population Data: Periodically re-checking the variant's frequency in large, diverse population databases like gnomAD. A high frequency in healthy populations argues against pathogenicity [9].

- Consultation with a Genetics Professional: An abbreviated or e-consult with a clinical geneticist or molecular geneticist can help triage VUSs and determine the most appropriate next steps [9].

Genetic Landscape of POI: Key Data

Table 1: Summary of Genetic Findings from a Large-Scale POI WES Study (n=1,030) [3]

| Genetic Finding | Number of Cases | Contribution to Cohort | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| P/LP in Known Genes | 193 | 18.7% | Spanning 59 known POI-causative genes |

| Monoallelic Variants | 155 | 15.0% | Single heterozygous P/LP variants |

| Biallelic Variants | 24 | 2.3% | P/LP variants in both copies of a gene |

| Multiple Variants (Multi-het) | 14 | 1.4% | P/LP variants in different genes in one individual |

| Primary Amenorrhea (PA) | |||

| 31 / 120 | 25.8% | Higher frequency of biallelic/multi-het variants | |

| Secondary Amenorrhea (SA) | |||

| 162 / 910 | 17.8% | Mostly monoallelic variants |

Table 2: Categorization of Genes Implicated in POI Pathogenesis [1] [3]

| Functional Category | Example Genes | Primary Role in Ovarian Function |

|---|---|---|

| Meiosis & DNA Repair | HFM1, MSH4, SPIDR, MCM8, MCM9, BRCA2 |

Homologous recombination, DNA double-strand break repair, meiotic progression |

| Folliculogenesis & Ovulation | GDF9, BMP15, NR5A1, FOXL2 |

Follicle development, growth, and maturation; steroidogenesis |

| Gonadogenesis | NR5A1 |

Early ovarian development and formation |

| Metabolic & Mitochondrial | EIF2B2, POLG, ACAD9 |

Cellular energy production, metabolism, and overall oocyte health |

| Autoimmune Regulation | AIRE |

Immune system tolerance, prevention of autoimmune oophoritis |

| Chromosomal & Syndromic | FMR1 (premutation) |

RNA toxicity leading to accelerated follicle depletion |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Genetic POI Research

Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) for Variant Discovery

Objective: To identify rare coding variants associated with POI in a hypothesis-free manner [3] [4].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood of well-phenotyped POI patients and select controls. Ensure informed consent and IRB approval [4].

- Library Preparation & Enrichment: Fragment DNA and prepare sequencing libraries using a kit (e.g., Agilent SureSelect). Hybridize and capture the exonic regions [4].

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on a platform such as Illumina HiSeq2000 to achieve sufficient coverage (e.g., >50x) [4].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Variant Calling: Map sequence reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) and call variants (SNVs, indels).

- Variant Filtering: Filter against population frequency databases (e.g., gnomAD, 1000 Genomes) to remove common variants (MAF > 0.01). Prioritize rare, protein-altering variants (nonsense, frameshift, splice-site, missense) [3] [4].

- Variant Annotation & Prioritization: Use tools like CADD and PolyPhen-2 to predict pathogenicity. Cross-reference with known POI gene panels and perform case-control burden analysis to identify genes with a significant excess of LoF variants [3].

Functional Validation of a VUS via Segregation Analysis

Objective: To determine if a VUS co-segregates with the POI phenotype within a family, providing evidence for or against its pathogenicity [9] [8].

Methodology:

- Family Member Recruitment: Identify and recruit available first- and second-degree relatives of the proband, including both affected and unaffected individuals.

- Genotyping: Perform Sanger sequencing or targeted genotyping for the specific VUS in all recruited family members.

- Segregation Analysis:

- For an Autosomal Dominant Model: The variant should be present in all affected family members and absent in unaffected ones. Penetrance may be incomplete.

- For an Autosomal Recessive Model: The proband should have biallelic variants. Parents are typically heterozygous carriers.

- De novo status, where the variant is present in the proband but absent in both parents, provides strong evidence for pathogenicity [9] [8] [10].

- Interpretation: Consistent co-segregation supports a upgrade of the VUS to "Likely Pathogenic," while finding the variant in a clearly unaffected adult relative makes pathogenicity less likely [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Genetic POI Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Agilent SureSelect Kit | Target enrichment for whole-exome sequencing | Captures exonic regions from genomic DNA libraries [4] |

| Illumina Sequencing Platform | High-throughput DNA sequencing | Platforms like HiSeq2000 generate short-read sequence data [4] |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Validation and segregation studies | Confirms variants identified by NGS in proband and family members [4] |

| gnomAD Database | Population frequency filtering | Critical for filtering out common polymorphisms [3] [4] |

| CADD & PolyPhen-2 | In silico pathogenicity prediction | Computational tools to prioritize damaging missense variants [3] [4] |

| ACMG/AMP Guidelines | Variant classification framework | Standardized criteria for classifying variants as P, LP, VUS, LB, or B [9] [3] |

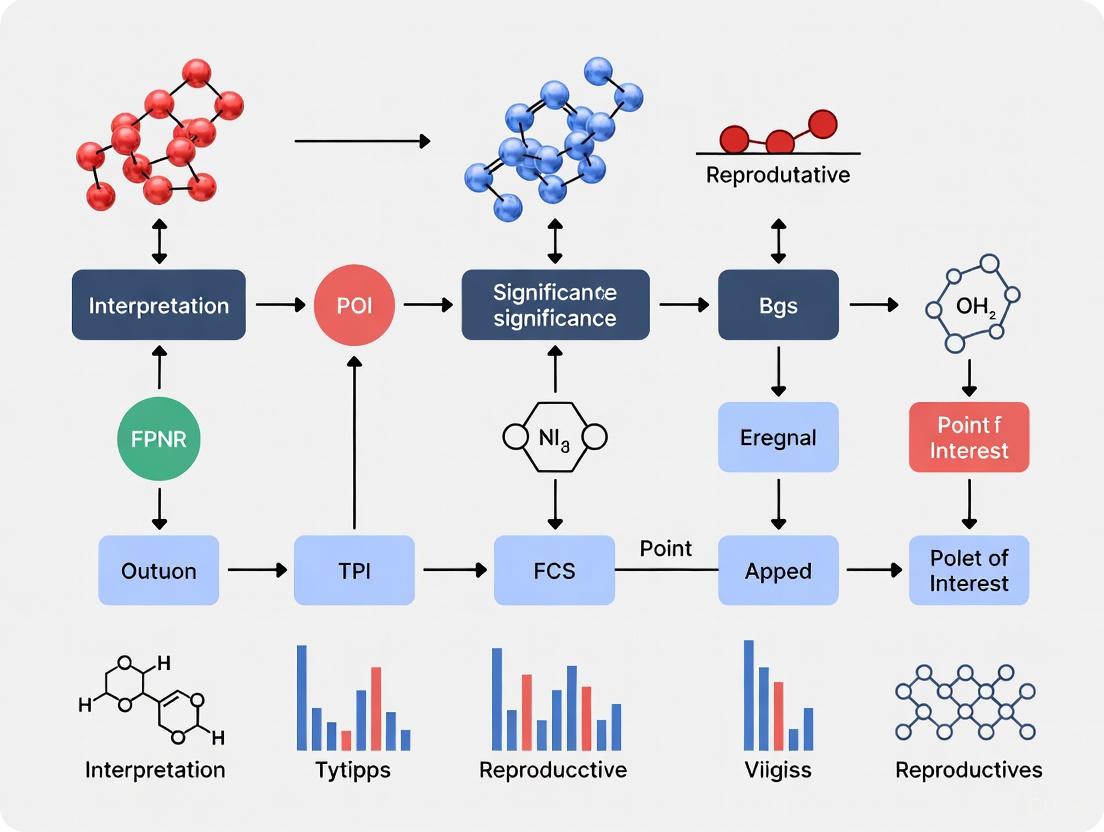

Workflow Diagram: From Patient to VUS Interpretation

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for genetic analysis and VUS interpretation in POI research.

FAQs: Genetic Architecture of POI

Q1: What is the estimated genetic contribution to Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI)? Genetic factors play a pivotal role in POI, contributing to approximately 20-25% of diagnosed cases [11]. A large-scale whole-exome sequencing study of 1,030 patients identified pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in known POI-causative genes in 18.7% of cases, with an additional 4.8% attributed to novel candidate genes, bringing the total genetic contribution to 23.5% [12]. The genetic contribution is significantly higher in patients with primary amenorrhea (25.8%) compared to those with secondary amenorrhea (17.8%) [12].

Q2: How are POI-associated genes functionally categorized? POI-associated genes can be systematically classified based on their biological roles in ovarian development and function. The main categories and their representative genes are summarized in the table below [11] [12] [13]:

Table: Functional Classification of POI-Associated Genes

| Functional Category | Biological Process | Key Representative Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Meiosis & DNA Repair | Homologous recombination, DNA damage repair, meiotic nuclear division | HFM1, SPIDR, BRCA2, MCM8, MCM9, MSH4, SHOC1, SLX4 |

| Ovarian & Follicular Development | Gonadogenesis, folliculogenesis, follicle activation | NOBOX, FIGLA, NR5A1, BMP15, GDF9, FOXL2 |

| Metabolic Pathways | Glycosylation, galactose metabolism | GALT, PMM2 |

| Mitochondrial Function | Mitochondrial metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation | AARS2, CLPP, POLG, TWNK, HADHB, CPT1A |

| Autoimmune Regulation | Immune tolerance, endocrine autoimmunity | AIRE |

| Chromosomal & Syndromic | X-chromosome related, syndromic forms | FMR1 (premutation), Turner Syndrome (45,X) |

Q3: What is the role of mitochondrial genes in POI pathogenesis? Mitochondrial dysfunction is a significant contributor to POI, affecting multiple aspects of ovarian function. Mitochondrial genes play crucial roles in meeting the energy demands of oogenesis and follicle maturation and are also involved in follicular atresia [14]. Key mechanisms include:

- Impaired Mitochondrial Dynamics: Deletion of mitochondrial fusion gene

Mfn2in oocytes leads to impaired oocyte maturation and follicle development, while targeted deletion of the fission geneDrp1reduces oocyte quality [14]. - Metabolic Dysregulation: Recent bioinformatic studies identified 119 mitochondria-related differentially expressed genes (MitoDEGs) in POI, including

Hadhb,Cpt1a,Mrpl12, andMrps7, which were validated in POI models and human granulosa cells [14]. - Oxidative Stress & Apoptosis: Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to changes in metabolic pathways, triggering inflammatory responses, disrupting reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis, and inducing cell apoptosis, ultimately leading to POI development [14].

Troubleshooting Genetic Experiments in POI Research

Challenge: Interpreting Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in POI Genes

Problem: A VUS is identified in a known POI gene during genetic testing, and its clinical significance cannot be determined.

Solution: Implement a multi-step validation protocol to assess VUS pathogenicity.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for VUS Interpretation

| Research Reagent | Specific Function/Application | Example Use Case in POI |

|---|---|---|

| Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit [15] | Whole exome sequencing library construction | Comprehensive variant detection in POI patient cohort |

| SurePrint G3 Human CGH Microarray 4×180 K [16] | Copy Number Variation (CNV) identification | Detection of chromosomal structural abnormalities |

| Custom Capture Design (163 genes) [16] | Targeted NGS of ovarian function-related genes | Focused screening of known and candidate POI genes |

| AlphaFold-predicted model & DynaMut2 [15] | Protein structure prediction and stability analysis | Assessing structural impact of CHEK1 A26G variant |

| DESeq2 R Package [15] | Differential gene expression analysis from RNA-Seq | Identifying mis-regulated pathways in mutant cells |

| rMATS software [15] | Alternative splicing event analysis | Detecting aberrant splicing due to genetic variants |

Experimental Protocol: Functional Validation of VUS

Step 1: Computational Pathogenicity Prediction

- Utilize in silico tools (MutationTaster, PANTHER, PolyPhen-2) for initial pathogenicity assessment [15].

- Perform protein structural analysis using AlphaFold-predicted models and stability change prediction with DynaMut2 (e.g., ΔΔG value of -0.98 kcal/mol for CHEK1 A26G suggests destabilizing effect) [15].

Step 2: In Vitro Functional Studies

- Clone the wild-type and mutant (VUS) allele into mammalian expression vectors with appropriate tags (e.g., HA tags for detection) [15].

- Transfert constructs into suitable cell lines (e.g., 293FT cells for high transfection efficiency) and confirm protein expression and localization via immunofluorescence and Western blotting [15].

- Compare protein expression levels between wild-type and mutant (relative to GAPDH) to assess stability effects [15].

Step 3: Transcriptomic Analysis

- Perform RNA sequencing on cells expressing wild-type versus mutant protein.

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using DESeq2 package (p-value <0.05, FDR <0.05) [15].

- Analyze alternative splicing events using rMATS software (FDR <0.05, inclusion-level difference >5%) [15].

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., GO, KEGG) to identify affected biological processes.

VUS Interpretation Workflow

Challenge: Low Diagnostic Yield in POI Genetic Testing

Problem: Despite comprehensive testing, a significant proportion of POI cases (approximately 70-80%) remain without a definitive genetic diagnosis.

Solution: Implement a multi-modal genetic testing approach.

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive Genetic Screening for POI

Step 1: Chromosomal and FMR1 Analysis

- Perform standard karyotyping to identify X-chromosome abnormalities (e.g., Turner Syndrome, Trisomy X) which account for 4-12% of POI cases [11] [16].

- Conduct FMR1 premutation testing for CGG repeat expansions, a common genetic cause of POI [16].

Step 2: Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis

- Utilize array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) with platforms such as SurePrint G3 Human CGH Microarray 4×180K [16].

- Analyze CNVs with minimum resolution of 60 kb along the genome, focusing on known POI critical regions (Xq13.1-Xq21.33 and Xq24-Xq27) [11] [16].

Step 3: Next-Generation Sequencing

- Employ whole-exome sequencing (WES) using capture kits (e.g., Agilent SureSelect) for comprehensive variant detection [12] [15].

- Alternatively, use targeted NGS panels covering known and candidate POI genes (e.g., 163-gene custom capture design) [16].

- Implement rigorous variant filtering: exclude common variants (MAF >0.01 in gnomAD or control databases), focus on loss-of-function and predicted damaging missense variants [12].

Step 4: Data Integration and Analysis

- Integrate findings from multiple genetic tests to identify compound heterozygous or oligogenic contributions.

- Correlate genetic findings with clinical presentation (primary vs. secondary amenorrhea), as genetic contribution differs significantly between these groups [12].

Advanced Research Methodologies

Integrative Bioinformatics Approach for Mitochondrial-Immune Interactions

Background: Mitochondrial dysfunction and immune dysregulation are interconnected in POI pathogenesis, but their interplay remains poorly understood [14].

Experimental Protocol: Identifying Mitochondrial-Related Gene Signatures

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Obtain transcriptomic data from public repositories (NCBI GEO: GSE128240, GSE233743, GSE39501) [14].

- Preprocess expression values using R package "limma" [14].

- Analyze single-cell RNA sequencing data (e.g., GSE200612) to elucidate cell-type specific expression [14].

Step 2: Identification of Mitochondria-Related Differentially Expressed Genes (MitoDEGs)

- Identify DEGs between normal and POI ovarian tissues (p <0.05, |logFC| >1) using "limma" package [14].

- Cross-reference DEGs with mitochondrial gene catalog (MitoCarta 3.0, 1140 genes) to identify MitoDEGs [14].

- Perform functional enrichment analysis (GSEA, GO, KEGG) using "clusterProfiler" package [14].

Step 3: Protein-Protein Interaction and Hub Gene Identification

- Construct PPI networks using STRING database [14].

- Identify hub genes using CytoHubba and MCODE plugins in Cytoscape [14].

- Validate hub genes (e.g.,

Hadhb,Cpt1a,Mrpl12,Mrps7) in POI models and human granulosa cells using RT-qPCR and Western blot [14].

Step 4: Immune Infiltration and Correlation Analysis

- Analyze immune cell infiltration using bioinformatic tools (e.g., Rank-In) [14].

- Perform correlation analysis between hub-MitoDEGs and immune-related genes/cells [14].

- Identify potential therapeutic agents using cMap database [14].

Mitochondrial Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

Research Recommendations and Future Directions

Enhancing VUS Interpretation: Develop POI-specific functional assays to characterize VUS in genes involved in key biological processes like meiosis (HFM1, MCM8, MCM9), mitochondrial function (TWNK, CPT1A), and folliculogenesis (NOBOX, FIGLA) [11] [12] [15].

Exploring Oligogenic Inheritance: Investigate potential oligogenic contributions to POI, where combinations of variants in multiple genes may collectively contribute to the phenotype, potentially explaining cases where single-gene variants show incomplete penetrance [13].

Standardizing Genetic Testing Protocols: Establish consensus guidelines for comprehensive POI genetic testing that includes chromosomal analysis, FMR1 testing, CNV detection, and next-generation sequencing to maximize diagnostic yield [16] [12].

Integrating Multi-Omics Data: Combine genomic data with transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic profiles to identify novel regulatory mechanisms and biomarkers for POI, particularly focusing on mitochondrial-immune interactions [14].

Definition and Core Concepts

What is a Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS)?

A Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) is a genetic variant that has been identified through genetic testing but whose significance to the function or health of an organism is not known [17]. In clinical practice, the term "variant" is favored over "mutation" as it describes an allele without inherently connoting pathogenicity [17].

The interpretation of DNA variants is fundamental to personalized medicine, enabling precise diagnosis and treatment selection [18]. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), and the College of American Pathologists (CAP) have established a standardized five-tier system for classifying variants [19] [17]:

- Pathogenic (P): Well-documented to cause disease, meeting stringent criteria such as evidence from well-established functional studies or identification in multiple unrelated individuals with the disease [17].

- Likely Pathogenic (LP): Strong evidence of being disease-causing but lacking definitive proof, indicating greater than 90% certainty of being pathogenic [19] [17].

- Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS): Unknown or conflicting clinical significance; insufficient evidence to determine if the variant is disease-causing [19] [17].

- Likely Benign (LB): Unlikely to be causative of disease, with more than 90% certainty that the variant is not causative for a disease [17].

- Benign (B): Not disease-causing, usually observed at high frequencies in population databases with strong evidence against pathogenic effect [17].

Figure 1: Variant Classification Workflow Following ACMG/AMP Guidelines

Current Landscape and Quantitative Data

The Burden of VUS in Clinical Practice

Variants of Uncertain Significance represent a significant challenge in genomic medicine. More than 70% of all unique variants in the ClinVar database are labeled as VUS [20]. The rate of VUS identification has grown over time with the increased adoption of genetic testing [20].

Table 1: VUS Reclassification Rates Across Studies

| Study Focus | Sample Size | Reclassification Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multicenter Cancer Study [21] | 2,715 individuals with 3,261 VUS | 8.1% overall | 11.3% of reclassified VUS resulted in clinically actionable findings; 4.6% subsequently changed clinical management |

| Tumor Suppressor Genes [22] | 128 unique VUS | 31.4% reclassified as likely pathogenic using new ClinGen criteria | Highest reclassification rate in STK11 (88.9%) |

| Multi-Institutional Real-World Evidence [23] | VUS across 20 hereditary cancer and cardiovascular genes | 32% of VUS carriers | 99.7% reclassified to Benign/Likely Benign; 0.3% to Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic |

Racial and ethnic disparities exist in VUS reclassification. A multicenter study found that compared to their prevalence in the overall sample, reclassification rates for Black individuals were higher (13.6% vs. 19.0%), whereas the rates for Asian individuals were lower (6.3% vs. 3.5%) [21].

The two-year prevalence of VUS reclassification remained steady between 2014 and 2019, suggesting consistent reinterpretation efforts over time [21].

Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Variant Reclassification Frameworks

Several advanced methodologies have been developed to improve VUS reinterpretation:

Real-World Evidence (RWE) Approach A novel RWE approach integrates de-identified, longitudinal clinical data with variant carriers and non-carriers identified from exome or genome sequence data across large-scale clinicogenomic datasets [23]. This method enables rigorous variant-specific case-control analyses from population data by:

- Compiling phenotypes for established gene-level disease associations from longitudinal medical records

- Applying statistically robust case-control analyses

- Systematically applying RWE to all variants, including previously identified VUS in clinically relevant genes

New ClinGen PP1/PP4 Criteria Recent Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) guidance focuses on cosegregation (PP1) and phenotype-specificity criteria (PP4) based on the observation that phenotype specificity could provide a greater level of pathogenicity evidence [22]. This point-based system assigns:

- Pathogenic evidence: 1 (supporting), 2 (moderate), 4 (strong), and 8 (very strong) points

- Benign evidence: -1 (supporting), -2 (moderate), and -4 (strong) points

- Classification thresholds: ≥10 (pathogenic), 6–9 (likely pathogenic), 0–5 (VUS), -1 to -6 (likely benign), ≤-6 (benign)

Figure 2: Advanced VUS Reclassification Methodologies

Non-Coding Variant Interpretation

Most clinical genetic testing has traditionally focused on protein-coding regions, but non-coding variants play an increasingly recognized role in penetrant disease [24]. Key considerations for non-coding variants include:

- Defining candidate regulatory elements: promoters, enhancers, repressors, splice regions, untranslated regions (UTRs)

- Understanding mechanisms: effects on splicing, transcription, translation, RNA processing and stability, chromatin interactions

- Adapting ACMG/AMP guidelines for non-coding contexts, as current guidelines primarily address protein-coding variants [24]

Non-coding region variants are significantly under-ascertained in clinical variant databases because these regions are often excluded from capture regions or removed during bioinformatic processing [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for VUS Interpretation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Databases | ClinVar, dbSNP, dbVar, gnomAD | Repository for clinically significant variants and population frequencies |

| In Silico Predictors | REVEL, SpliceAI, CADD, SIFT, GERP | Computational prediction of variant impact using AI and statistical methods |

| Automated Interpretation Tools | PathoMAN, VIP-HL | Automate evaluation of ACMG/AMP guideline criteria by integrating diverse data sources |

| Functional Assays | Multiplexed functional assays [20] | High-throughput experimental assessment of variant impact |

| Clinico-Genomic Datasets | Helix Research Network, UK Biobank, All of Us | Large-scale datasets linking genomic and clinical data for RWE approaches |

| Stipuleanoside R2 | Stipuleanoside R2, CAS:96627-72-4, MF:C53H84O23, MW:1089.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-Biotinol | D-Biotinol, CAS:53906-36-8, MF:C10H18N2O2S, MW:230.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What should I do when a VUS is identified in a patient with a strong personal and family history of disease?

A: First, ensure comprehensive phenotyping and detailed family history collection. Consider implementing the new ClinGen PP1/PP4 criteria, which assign higher weight to phenotype specificity [22]. For genes with high locus homogeneity (where only one gene explains the phenotype), this approach can assign up to five points solely from phenotype specificity criteria. Additionally, explore functional assays to gather additional evidence of pathogenicity [20].

Q: How can we reduce the high rate of VUS in clinical testing?

A: Implement systematic approaches including:

- Leverage large-scale real-world evidence: Integrating RWE from clinicogenomic datasets is projected to resolve over 50% of VUS carriers once longitudinal databases are available for approximately 3 million individuals [23].

- Apply updated classification criteria: Use disease-specific guidelines like the new ClinGen PP1/PP4 criteria, which significantly improve reclassification rates for tumor suppressor genes [22].

- Utilize automated interpretation tools: These can help standardize variant assessment, though expert oversight remains crucial, particularly for VUS interpretation [18].

Q: What are the best practices for handling VUS in non-coding regions?

A: For non-coding variants:

- Define regulatory elements relevant to your gene of interest, including promoters, enhancers, and untranslated regions [24].

- Use specialized prediction tools for non-coding variant impact assessment.

- Consider experimental validation of regulatory function when possible.

- Consult emerging guidelines for adapting ACMG/AMP criteria to non-coding regions [24].

Q: How reliable are automated variant interpretation tools for VUS classification?

A: Automated tools demonstrate high accuracy for clearly pathogenic/benign variants but show significant limitations with VUS [18]. While these tools enhance efficiency by automating evidence collection and criteria evaluation, expert oversight is still needed in clinical contexts, particularly for VUS interpretation [18]. Tools vary in their automation approaches, data sources, and criteria implementation, so careful selection and validation are essential.

Q: What is the typical timeframe for VUS reclassification, and how can we facilitate this process?

A: Reclassification timeframes vary significantly. One study found the two-year prevalence of VUS reclassification remained steady between 2014 and 2019 [21]. To facilitate reclassification:

- Participate in data sharing initiatives such as ClinVar to contribute to community knowledge [20].

- Establish laboratory protocols for periodic variant reassessment (e.g., every three years) [22].

- Implement systems to efficiently return reinterpreted genetic test results to patients and providers [21].

- Utilize updated classification criteria as they become available to maximize current knowledge application [22].

Table 1: Reported Prevalence of VUS and Pathogenic Variants in POI Cohort Studies

| Study Cohort Size | Total Cases with P/LP/VUS | Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic (P/LP) Variants | Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 patients | 16/28 (57.1%) | 9/28 (32.1%) causal SNVs/CNVs | 7/28 (25.0%) | First study combining array-CGH and NGS in same POI cohort. | [16] |

| 68 Turkish patients | 4/68 (5.9%) | 1 likely pathogenic variant | 3 VUS in NOBOX, GDF9, STAG3 | First genetic epidemiology study in Türkiye with a 26-gene panel. | [25] |

| 1,030 patients | 193/1030 (18.7%) with P/LP | 195 P/LP variants in 59 genes | 75 VUS functionally evaluated (55 confirmed deleterious) | Large-scale WES study; 38 VUS were upgraded to LP after functional assays. | [26] |

| 500 Chinese patients | 72/500 (14.4%) with P/LP | 61 P/LP variants in 19 genes | Not explicitly quantified | 58/61 (95.1%) of the identified P/LP variants were novel. | [27] |

| 151 Belgian patients | 2/151 (1.3%) with NOBOX variants | 1 pathogenic variant | 1 VUS in NOBOX (c.259C>A) | Highlights discordance between ACMG classification and in vitro functional data. | [28] |

Experimental Protocols for VUS Interpretation

Protocol: Comprehensive Genetic Screening Workflow for POI

Objective: To identify and classify genetic variants, including VUS, in patients with idiopathic Premature Ovarian Insufficiency.

Materials:

- DNA extracted from patient peripheral blood samples.

- Array-CGH platform (e.g., Agilent SurePrint G3 Human CGH Microarray 4x180 K).

- Next-Generation Sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina NextSeq 550).

- Custom-designed gene panels or whole-exome capture kits.

- Bioinformatics analysis software (e.g., Alissa Align&Call, CytoGenomics).

Procedure:

- Patient Selection & DNA Extraction: Select patients meeting diagnostic criteria for POI (amenorrhea for >4 months before age 40 and elevated FSH >25 IU/L). Exclude other known causes (karyotype abnormalities, FMR1 premutation, autoimmune, or iatrogenic causes). Extract high-quality DNA [16].

- Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis:

- Perform array-CGH following manufacturer's protocols.

- Use bioinformatics software to identify CNVs with a minimum resolution of 60 kb.

- Annotate identified CNVs using databases like DECIPHER and ClinGen [16].

- Sequencing Analysis (Targeted Panel or WES):

- Variant Filtering and Annotation:

- Variant Classification:

- Functional Validation (For VUS Upgrade):

- For a subset of VUS, particularly in key biological pathways, proceed with functional assays.

- Example: For VUS in the FSHR gene, use cell culture models transfected with wild-type and mutant plasmids. Assess cell surface expression of the receptor and measure downstream signaling (e.g., cAMP production) in response to FSH stimulation [29].

Figure 1: Genetic Screening and VUS Interpretation Workflow for POI.

Protocol: Functional Assay for VUS in the FSHR Gene

Objective: To determine the functional impact of a VUS in the Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor (FSHR) gene on receptor expression and signaling.

Materials:

- Plasmids containing the common (wild-type) FSHR allele and plasmids with the VUS.

- Cell line suitable for transfection (e.g., HEK293).

- FSH hormone.

- Antibodies for FSHR detection (for surface expression).

- cAMP assay kit (e.g., competitive ELISA or HTRF).

Procedure:

- Cell Transfection: Transfect cells with separate plasmids: wild-type FSHR, each VUS individually, both VUS together (in trans), and an empty vector control [29].

- Cell Surface Expression Analysis:

- Measure the cell surface expression of FSHR using a technique like flow cytometry or immunofluorescence with FSHR-specific antibodies.

- Compare the expression level of the VUS-containing receptors to the wild-type receptor. A marked reduction (e.g., up to 93% as reported) supports a deleterious effect [29].

- cAMP Production Assay:

- Stimulate transfected cells with a saturating concentration of FSH.

- Lyse cells and measure intracellular cAMP production using a commercial assay kit.

- Compare cAMP production in cells expressing VUS to those expressing the wild-type receptor. A significant reduction (e.g., ~50%) indicates impaired downstream signal transduction [29].

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: A significant number of VUS in our POI cohort are in the NOBOX gene, but in silico tools and ACMG criteria classify them as benign or VUS, despite literature suggesting a role in POI. How should we proceed?

- Problem: Discordance between population frequency-based ACMG classification and biological evidence for POI-specific genes.

- Solution:

- Consider Gene-Specific Caveats: Be aware that ACMG criteria like BS1 (allele frequency greater than expected for disorder) and BS2 (observed in a healthy adult) can be problematic for POI. The condition has a prevalence of 1-3.7%, and pathogenic variants can be carried asymptomatically by male relatives, skewing population database frequencies [28].

- Prioritize Functional Evidence: Proceed with functional studies, as was done for NOBOX variants showing nuclear localization impairment and dominant-negative effects, even for some ACMG-classified "benign" variants [28].

- Investigate Oligogenic Models: Consider that the phenotypic expression of a VUS in NOBOX might depend on the presence of variants in other genes (oligogenic inheritance) [28] [27].

FAQ 2: Our diagnostic pipeline has identified a VUS. What are the established pathways for gathering additional evidence to re-classify it?

- Problem: Lack of evidence to resolve a VUS.

- Solution:

- Segregation Analysis: Test first-degree relatives, particularly affected and unaffected females, to see if the variant co-segregates with the POI phenotype. This can provide strong evidence (ACMG codes PP1/BS4) [16] [27].

- Functional Assays: As detailed in Protocol 2.2, perform in vitro experiments to demonstrate a deleterious impact on protein function (e.g., reduced cell surface expression, impaired signaling, altered transcriptional activity). This provides PS3 evidence [29] [26].

- Look for Biallelic or Oligogenic Hits: In recessive disorders, finding a second pathogenic variant in trans (on the other allele) can clarify the pathogenicity of the first VUS. Also, search for potential additional VUS in interacting genes that might have a cumulative effect [27].

FAQ 3: We are designing a genetic study for POI. What is the relative merit of a targeted gene panel versus Whole Exome Sequencing (WES)?

- Problem: Uncertainty in selecting the optimal sequencing strategy.

- Solution:

- Targeted Panels are simpler, more cost-effective, and allow for deep coverage of known POI-associated genes. They are ideal for focused diagnostic screening [29] [25].

- WES is more comprehensive and allows for the discovery of novel candidate genes and oligogenic interactions. It is the preferred tool for research aiming to expand the genetic landscape of POI [26] [30]. The decision should align with the primary goal of the study: routine diagnosis or novel gene discovery.

Key Signaling Pathways & Genetic Networks

Table 2: Key Biological Processes and Associated POI Genes Frequently Harboring VUS

| Biological Process | Description | Example Genes | Challenges with VUS Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meiosis & DNA Repair | Ensures accurate chromosome segregation and genomic integrity in germ cells. | MSH4, MSH5, HFM1, SPIDR, STAG3 | Functional assays are complex; variants may not show overt phenotypes in somatic cells. |

| Folliculogenesis | Regulates the development and activation of ovarian follicles. | NOBOX, FIGLA, GDF9, BMP15 | Genes are ovary-specific, limiting functional study options; strong candidate but often VUS. |

| Hormone Signaling & Receptors | Mediates communication between the pituitary and the ovary. | FSHR, BMPR1A/B, ESR2 | In vitro assays (see Protocol 2.2) are well-established but resource-intensive. |

| Metabolic & Mitochondrial | Provides energy and supports fundamental cellular functions in the oocyte. | PMM2, TWNK, EIF2B2 | Can cause syndromic or isolated POI; phenotype can be variable, complicating classification. |

Figure 2: Genetic Network of POI showing VUS Hotspots.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for POI Genetic Research and VUS Functional Analysis

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) is a clinically heterogeneous condition characterized by the loss of ovarian function before age 40, presenting with menstrual disturbances and elevated Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) levels [31]. The diagnostic landscape has evolved, with recent guidelines indicating that only one elevated FSH measurement (>25 IU/L) is now required for diagnosis, replacing the previous requirement for two separate measurements [5].

Historically, the majority of POI cases were classified as idiopathic due to limited diagnostic capabilities. However, contemporary research reveals a significant shift in this etiological distribution. A comparative analysis of historical (1978-2003) and contemporary (2017-2024) cohorts demonstrates a dramatic reduction in idiopathic cases from 72.1% to 36.9%, coupled with a more than fourfold increase in identifiable iatrogenic causes (from 7.6% to 34.2%) and a doubling of autoimmune cases [31]. This transformation reflects advances in diagnostic precision and changes in patient populations, including improved survival rates for conditions requiring gonadotoxic treatments.

Table: Comparative Analysis of POI Etiology Over Time

| Etiological Category | Historical Cohort (1978-2003) | Contemporary Cohort (2017-2024) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic | 11.6% | 9.9% | Stable |

| Autoimmune | 8.7% | 18.9% | 2.2x increase |

| Iatrogenic | 7.6% | 34.2% | 4.5x increase |

| Idiopathic | 72.1% | 36.9% | 49% decrease |

Understanding Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in POI Research

The Fundamental Nature of VUS

Variants of Uncertain Significance represent genetic changes whose association with disease risk is currently unknown. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG/AMP) defines VUS as variants that "do not fulfill criteria using either pathogenic or benign evidence sets, or the evidence for benign and pathogenic is conflicting" [32]. In the context of POI research, VUS present a significant interpretive challenge that reflects the natural biological heterogeneity of human populations.

Current data from ClinVar indicates that VUS constitute the largest single category of genetic variants (44.6% of all germline variation records), outnumbering both pathogenic and benign variants combined [32]. This distribution underscores that VUS are not an intermediate category between pathogenic and benign variants, but rather represent variants with insufficient or conflicting evidence for classification. The persistence of VUS arises from multiple biological factors including differential penetrance, modifier genes, allele dosage effects, and environmental influences [32].

VUS and POI Heterogeneity

The clinical heterogeneity of POI mirrors the biological complexity of VUS interpretation. POI presents across a spectrum of severity, age of onset, and associated health implications, making straightforward genotype-phenotype correlations challenging. This heterogeneity means that the same genetic variant may manifest differently across individuals due to:

- Penetrance Variation: Some carriers of a POI-associated variant may experience complete ovarian failure while others maintain partial function

- Modifier Genes: Genetic background influences phenotypic expression

- Environmental Interactions: Factors like chemical exposures can modify genetic risk

- Allele Dosage Effects: Haploinsufficiency and gene dosage sensitivity vary by gene

Frequently Asked Questions: VUS Troubleshooting in POI Research

Q1: We've identified a VUS in a POI patient with no family history. How should we proceed with interpretation?

Begin by implementing a network-based gene association approach. Tools like VariantClassifier utilize biological evidence-based networks including protein-protein interaction, co-expression, co-localization, genetic interaction, and common pathways networks to contextualize your VUS [33]. The methodology involves:

- Extract known POI-associated variants and genes from ClinVar

- Map your VUS onto gene-association networks

- Select an informative subnetwork by identifying neighboring nodes of the variant gene

- Extract variants from large-scale data for all genes in the subnetwork

- Apply polygenic risk models to detect groups of synergistically acting variants [33] This approach significantly improves risk prediction accuracy by moving beyond single-variant analysis to consider variant synergies.

Q2: What functional evidence is most valuable for VUS reclassification in POI?

Prioritize evidence that demonstrates biological impact on ovarian function. Key experimental approaches include:

- Protein Degradation Assays: Utilize Targeted Protein Degradation tools to assess the functional impact of VUS. Heterobifunctional small molecule degraders can help determine if the variant affects protein stability or function [34]

- Hormone Response Testing: Evaluate the variant's impact on folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis pathways

- Family Segregation Studies: When possible, track variant inheritance patterns in affected and unaffected relatives

- Population Frequency Analysis: Compare variant frequency in POI cohorts versus control populations

Q3: How can we distinguish between pathogenic variants and VUS in genes with low penetrance for POI?

Low-penetrance genes require a quantitative framework for interpretation. Implement the following strategy:

- Calculate a synergy score using network-based methods that consider variant pairs and groups rather than individual variants in isolation [33]

- Incorporate protective variant analysis alongside pro-disease variants to create a more complete genetic risk profile

- Use polygenic risk scoring that aggregates the effects of multiple variants falling below traditional significance thresholds

- Apply functional validation using induced proximity platforms to assess the biological consequences of specific variants [34]

Q4: Our team found conflicting interpretations of the same VUS in different databases. How should we resolve this?

Conflicting interpretations reflect genuine biological heterogeneity rather than simply database errors. Resolution requires:

- Evidence Weighting: Prioritize functional evidence over computational predictions

- Cohort Specificity: Consider the ethnic and clinical characteristics of the populations in which the variant was observed

- Methodological Review: Evaluate the testing methodologies and classification criteria used by different submitters

- Expert Consultation: Refer to gene-specific variant interpretation committees when available, such as the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT) model [32]

Experimental Protocols for VUS Investigation in POI

Network-Based VUS Prioritization Workflow

The VarClass methodology provides a systematic approach for prioritizing VUS through network-based gene association [33].

Table: VarClass Pipeline Components

| Step | Process | Tools/Resources | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Input Generation | Extract known disease-associated variants | ClinVar database | Curated list of POI-related genes/variants |

| 2. Network Construction | Build biological evidence-based networks | GeneMANIA | Five network types: PPI, co-expression, co-localization, genetic interaction, pathways |

| 3. VUS Mapping | Place VUS onto constructed networks | Custom scripts | Network positioning of VUS relative to known genes |

| 4. Subnetwork Selection | Identify neighboring nodes of VUS gene | Network analysis tools | Informative subnetwork of biologically related genes |

| 5. Variant Extraction | Extract variants for all subnetwork genes | WES/WGS data | Expanded variant set for risk modeling |

| 6. Risk Modeling | Develop polygenic risk prediction models | Machine learning algorithms | Two models: with and without VUS under investigation |

| 7. Significance Assessment | Evaluate VUS impact on model performance | ROC analysis, IDI measures | Quantitative significance score for VUS |

Protocol Details:

- Begin by querying ClinVar for established POI-associated genes and variants to create a reference set [33]

- Construct comprehensive gene-association networks using GeneMANIA, incorporating multiple evidence types: physical interactions, genetic interactions, pathway sharing, and co-expression [33]

- Map your VUS of interest onto these networks based on their gene locations

- Extract the local subnetwork comprising direct neighbors and connecting nodes of the VUS gene

- Compile all variants within this subnetwork from your cohort data

- Develop two polygenic risk models: Model 1 includes all subnetwork variants; Model 2 excludes the specific VUS under investigation

- Compare model performance using Receiver Operating Characteristic curves and Integrated Discrimination Improvement metrics to quantify the VUS contribution to risk prediction [33]

Targeted Protein Degradation for Functional Validation

VUS Functional Degradation Workflow

Experimental Procedure:

- PROTAC Design: Select appropriate heterobifunctional degraders based on your target protein. Bio-Techne offers various degraders including PROTAC molecules, molecular glues, and TAG degraders [34]

- Cell Line Selection: Choose appropriate ovarian cell lines or create patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) differentiated into ovarian cell types

- Treatment Conditions: Apply degraders at varying concentrations (typically nM to μM range) and time points (hours to days)

- Ternary Complex Validation: Confirm induced proximity using co-immunoprecipitation or proximity-based assays

- Ubiquitination Assay: Detect ubiquitin conjugation to target protein using ubiquitination-specific antibodies or mass spectrometry

- Degradation Monitoring: Measure target protein levels over time via Western blot or Simple Western assays

- Functional Assessment: Evaluate downstream phenotypic consequences including hormone production, folliculogenesis markers, and apoptosis assays

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents for POI VUS Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Protein Degraders | PROTAC molecules, dTAG/aTAG degraders, Molecular glues [34] | Functional validation of VUS impact | Catalytic mode of action, target previously "undruggable" proteins, reversible effects |

| Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Components | E3 Ubiquitin Ligases (VHL, CRBN, SKP2), Cullin-Rbx complexes, Ubiquitination assay kits [34] | Mechanistic studies of VUS effects | Highly active enzymes, neddylated cullins available, compatibility with various substrates |

| Network Analysis Tools | VariantClassifier, GeneMANIA, GEMINI [33] | VUS prioritization and interpretation | Integration of multiple biological networks, synergy detection, handles VUS from WES/WGS |

| POI-Specific Assays | Hormone response assays, folliculogenesis markers, meiotic recombination tests | Functional characterization of ovarian impact | POI-relevant cellular contexts, measures key pathological processes |

| Custom Degrader Services | PROTAC panel builders, degrader building blocks, custom E3 ligase development [34] | Tailored solutions for novel VUS | Target-specific degrader design, access to novel E3 ligase ligands, custom chemistry |

| Huzhangoside D | Huzhangoside D | High-purity Huzhangoside D, a natural saponin for cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Rutarensin | Rutarensin, CAS:119179-04-3, MF:C31H30O16, MW:658.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Analytical Framework for VUS Interpretation

VUS Interpretation Decision Pathway

The evolving etiological spectrum of POI, with its marked shift from idiopathic to identifiable causes, underscores the critical importance of sophisticated VUS interpretation frameworks. The integration of network-based prioritization, functional validation through targeted protein degradation, and clinical correlation creates a powerful pipeline for transforming VUS into clinically actionable findings. As the field advances, this multidisciplinary approach will continue to reduce the proportion of idiopathic POI cases while providing deeper insights into ovarian biology and the complex genetic architecture underlying Premature Ovarian Insufficiency.

Methodological Frameworks and Tools for VUS Interpretation in POI

Foundational Concepts of Variant Classification

What is the fundamental principle of the ACMG/AMP guidelines? The 2015 ACMG/AMP guidelines provide a standardized framework for interpreting sequence variants in genes associated with Mendelian disorders. The core outcome of this process is the classification of each variant into one of five categories based on the weight and combination of evidence applied: Pathogenic (P), Likely Pathogenic (LP), Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS), Likely Benign (LB), or Benign (B) [35] [36]. These classifications use specific terminology to ensure consistency across clinical laboratories.

What defines a Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS)? A VUS is a genomic variant for which there is insufficient or conflicting evidence to conclude whether it is disease-causing (pathogenic) or harmless (benign) [10]. This classification encompasses a wide range of probabilities of pathogenicity, from 10% to 90% [10]. It is critical to note that a VUS is not considered clinically actionable, and clinical management decisions, such as screening or cascade testing of family members, should not be based on this finding alone [10].

Why are gene-specific guideline specifications necessary? The original ACMG/AMP guidelines were designed to be broadly applicable across all Mendelian genes. However, the 2015 publication itself anticipated that "those working in specific disease groups should continue to develop more focused guidance" [36]. To address this, initiatives like the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) have established Variant Curation Expert Panels (VCEPs). These expert panels create and publish detailed, gene-specific specifications for applying the ACMG/AMP criteria, which greatly improves classification consistency and accuracy for that gene-disease pair [37] [38]. For instance, a VCEP for the PALB2 gene advised against using 13 general codes, limited the use of six, and tailored nine others to create a final, optimized guideline [37].

A Step-by-Step Framework for VUS Interpretation in POI Research

The following workflow provides a structured approach for researchers interpreting variants in the context of Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI). It synthesizes the general ACMG/AMP criteria with the gene-specific specification process used by ClinGen VCEPs.

Step 1: Assemble Evidence for the Variant

Gather all available data for the variant, categorizing it into the following evidence types [39]:

- Population Data: Determine the variant's frequency in large population databases like gnomAD. A frequency significantly higher than the disease prevalence is strong evidence against pathogenicity [38].

- Computational and Predictive Data: Use in silico tools to predict the variant's impact on protein function (e.g., conservation, splice site effect).

- Functional Data: Review existing functional studies from the literature. "Well-established" assays that are analytically sound and reflect the biological environment can provide strong evidence [40].

- Case-Level and Clinical Data: Collect segregation data within families, information on de novo occurrence, and the patient's phenotype.

Step 2: Apply and Weight ACMG/AMP Criteria

Map the assembled evidence to the corresponding ACMG/AMP criteria. This is where gene-specific knowledge is critical.

- First, investigate if a ClinGen VCEP or other expert group has published specifications for your POI gene of interest. These specifications define how general criteria should be adapted (e.g., setting a gene-appropriate population frequency threshold for the BS1 criterion) [37] [38].

- Apply the criteria based on these customized rules. For example, the strength of functional evidence (PS3/BS3) can be modified to "Supporting" or "Moderate" based on the validation and performance of a specific assay [40].

Step 3: Combine Criteria for Classification

Follow the ACMG/AMP combining rules to reach a final classification. The table below outlines the general logic for pathogenic classifications. Note that the presence of conflicting evidence (e.g., a pathogenic criterion like PS1 and a benign criterion like BS1) will typically result in a VUS classification [41].

Step 4: Determine the Final Classification and Action

- If the variant classifies as Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic, it can be considered a definitive finding for the purposes of your research, with the understanding that LP variants have a >90% certainty of being disease-causing [36].

- If the variant remains a VUS, it should be prioritized for further study to gather additional evidence, such as functional assays or segregation data from more family members [10].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios (FAQs)

FAQ 1: We have a VUS with strong computational predictions of damage, but it is absent from population databases. Why is it not "Likely Pathogenic"?

This is a common scenario. Computational data (PP3) and absence from population databases (PM2) are typically considered supporting or moderate-level evidence. According to the ACMG/AMP combining rules, these evidence strengths alone are often insufficient to reach a Likely Pathogenic classification, which requires stronger evidence such as de novo occurrence (PS2) or well-established functional data (PS3) [35] [41]. The variant you describe is a classic "hot VUS" that is a high priority for gathering additional evidence, such as segregation or functional data, to enable reclassification [10].

FAQ 2: Our functional assay shows a damaging result for a VUS. When can we use this to upgrade the variant?

To use functional data as strong (PS3) evidence for pathogenicity, the assay must be "well-established." [40] This requires:

- Robust Validation: The assay should have been tested with a set of known pathogenic and benign control variants and demonstrated a high ability to distinguish between them.

- Biological Relevance: The assay should reflect the gene's biological function and the disease mechanism (e.g., loss-of-function, dominant negative).

- Technical Rigor: The experiment should include appropriate controls, replicates, and statistical analysis [40]. Without these parameters, the evidence strength may need to be downgraded to moderate (PS3Moderate) or supporting (PS3Supporting). ClinGen VCEPs often provide guidance on which specific assays for a gene meet this bar [40].

FAQ 3: How should we handle a VUS that is found in a patient with a compelling phenotype?

A compelling phenotype can be used as evidence (PP4), but it is usually a supporting-level criterion. Clinical management should be based on the personal and family history, not on the presence of the VUS [10] [41]. In a research context, you can:

- Perform Segregation Analysis: Test other affected and unaffected family members to see if the variant co-segregates with the disease.

- Seek Additional Evidence: Pursue functional studies or look for independent observations of the same variant in other cases.

- Leverage Team Expertise: Discuss the variant in a multi-disciplinary team setting where clinical, genetic, and functional data can be integrated to assess if the VUS can be reclassified [10].

Quantitative Framework for Evidence Integration

The ACMG/AMP guidelines are compatible with a Bayesian statistical framework, which allows for a quantitative interpretation of the evidence strength. The Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) working group of ClinGen has estimated the relative odds of pathogenicity for each evidence level [38]. This framework is useful for understanding the quantitative "weight" behind each criterion you apply.

Table 1: Bayesian Weights of ACMG/AMP Evidence Criteria

| Evidence Strength | Odds of Pathogenicity | Posterior Probability of Pathogenicity* |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting (P) | 2.08 : 1 | ~67.5% |

| Moderate (M) | 4.33 : 1 | ~81.2% |

| Strong (S) | 18.7 : 1 | ~94.9% |

| Very Strong (VS) | 350 : 1 | ~99.7% |

*Assuming a 0.1% prior probability of pathogenicity. Adapted from Tavtigian et al. (2018) as cited in [38].

Table 2: Example Combinations for Pathogenic Classifications

| Pathogenic Criteria Met | Combined Odds (Approx.) | Combined Probability (Approx.) | Final Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Strong (S) + 1 Moderate (M) | 81 : 1 | ~98.8% | Likely Pathogenic |

| 1 Very Strong (VS) | 350 : 1 | ~99.7% | Pathogenic |

| 2 Strong (S) | 350 : 1 | ~99.7% | Pathogenic |

| 1 Strong (S) + 2 Moderate (M) | 350 : 1 | ~99.7% | Pathogenic |

Table 3: Essential Resources for VUS Interpretation

| Resource / Reagent | Function in VUS Analysis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| gnomAD Database | Provides population allele frequency data to assess variant rarity. | Use the filtering allele frequency (FAF) to control for population substructure. Be mindful of adult-onset diseases in this dataset [38]. |

| ClinVar Database | A public archive of reports on genomic variants and their relationship to phenotype. | Helps identify if a VUS has been seen and interpreted by other labs, though interpretations may conflict [37]. |

| ClinGen VCEP Specifications | Gene- and disease-specific rules for applying ACMG/AMP criteria. | Check the ClinGen website for approved specifications for your gene of interest; these override the general guidelines [37] [42]. |

| In Silico Prediction Tools | Computational programs (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen-2) that predict the functional impact of a missense variant. | Results are considered supporting evidence (PP3 for damaging, BP4 for benign). Use a combination of tools for a more reliable prediction [35]. |

| Validated Functional Assays | Laboratory tests (e.g., in vitro, model organisms) that measure the biochemical consequence of a variant. | Must be "well-established" and validated with known controls to be used as strong (PS3/BS3) evidence [40]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Evidence Types

Protocol: Validating a Functional Assay for PS3/BS3 Application Based on the analysis of multiple VCEPs, the following parameters are critical for developing a functional assay that can be used as strong evidence for variant classification [40]:

- Define Disease Mechanism: First, establish the expected molecular effect for pathogenic variants in your gene (e.g., loss-of-function, gain-of-function, dominant negative). The assay must directly measure this specific function.

- Establish a Reference Range: Test a set of at least 10-15 known pathogenic and 10-15 known benign variant controls in your assay. This is essential for validation.

- Set a Quantitative Threshold: Based on the control results, define a clear, statistical threshold that distinguishes pathogenic from benign variants. The assay should have a high sensitivity and specificity (>90% is ideal for strong-level evidence).

- Incorporate Experimental Controls: Each experimental run must include:

- Positive Control: A known pathogenic variant.

- Negative Control: A known benign variant or wild-type.

- Technical Replicates: Perform a minimum of three independent experimental replicates to ensure robustness and reproducibility.

- Document and Publish: Fully document the assay protocol, validation data, and results for the VUS. Publication in a peer-reviewed journal strengthens the evidence.

Protocol: Gathering Segregation Data for PP1 Application

- Identify Family Members: Recruit as many first- and second-degree relatives of the proband as possible, both affected and unaffected.

- Perform Genotyping: Genotype all recruited family members for the VUS.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate a LOD score (logarithm of the odds) if the family structure is sufficiently large. As a rule of thumb, the PP1 criterion can be applied at a supporting strength if the variant is observed to co-segregate with disease in multiple affected family members. The strength can be upgraded to moderate or strong with a statistically significant LOD score [35].

Leveraging Population Genomics Databases (gnomAD, ClinVar) for Allele Frequency Analysis

Within Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) research, a genetic diagnosis is achieved in only 20-25% of cases, leaving a significant portion of patients without a known etiology [16]. The analysis of genetic variants, particularly the interpretation of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS), is therefore a critical component of POI research. Population genomics databases are indispensable tools in this process, enabling researchers to distinguish rare, potentially pathogenic variants from common benign polymorphism.

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for leveraging the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) and ClinVar to address common challenges in POI allele frequency analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

How do I filter variants based on population frequency in gnomAD?

A core task in POI research is filtering out variants that are too common in the general population to be responsible for a rare condition.

- Problem: A researcher needs to filter variants with a population frequency of less than 1% but is unsure which gnomAD field to use and how to interpret the values.

Solution:

- The

AF(Allele Frequency) field in gnomAD is expressed as a proportion, not a percentage [43]. A value of0.01corresponds to 1%. - For a strict filter against common variants, using the

popmax(maximum allele frequency across all specific populations) orAF_popmaxfield is recommended. This helps avoid missing a variant that is common in a specific population but rare globally [43]. - To select for variants with a frequency of <1%, you should filter where

AF_popmax < 0.01.

- The

Example Filtering Logic for a Rare Disease like POI:

Why does a variant have a high population frequency in gnomAD but is also listed as pathogenic in ClinVar?

Encountering a variant described as pathogenic in ClinVar that also has a high allele frequency in gnomAD is a common point of confusion.

- Problem: A putative pathogenic variant in a POI candidate gene (e.g., NOBOX, BMP15) is observed with a high frequency in gnomAD, which contradicts its supposed disease-causing role in a rare condition.

- Solution: This discrepancy is a major red flag and typically indicates one of the following issues [44] [45]:

- Misclassification in ClinVar: The variant's pathogenic classification may be erroneous. Older submissions might not have had access to large population data.

- Benign Founder Variant: The variant could be a benign founder variant that is common in a specific population.

- Reduced Penetrance: The variant might cause disease only in combination with other genetic or environmental factors.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check ClinVar Submissions: On the ClinVar variant page, review the number of submitters and the review status. Conflicts between submitters or a single submitter without expert review (e.g., zero stars) lower confidence in the pathogenic call [46] [45].

- Investigate Population-Specific Frequency: In gnomAD, drill down into the frequency within specific ancestral populations. A variant rare globally but common in one population might be a founder variant.

- Re-evaluate Pathogenicity: Use the ACMG/AMP guidelines. A high population frequency is strong evidence against pathogenicity (BS1 criterion) and should prompt a re-classification of the variant.

How can I integrate gnomAD constraint metrics into my analysis of POI candidate genes?

Not all genes are equally tolerant to genetic variation. gomAD's constraint metrics help identify genes that are intolerant to loss-of-function or missense variation.

- Problem: A researcher identifies a rare missense variant in a novel gene in a POI patient and wants to assess the gene's overall relevance to disease.

- Solution: Use gnomAD's loss-of-function observed/expected (oe) constraint score and the missense Z-score.

- A low LoF oe score (significantly < 0.35) indicates that the gene has fewer loss-of-function variants than expected, suggesting purifying selection and that it is likely essential—a hallmark of disease-associated genes [44].

- A high missense Z-score indicates intolerance to missense variation.

- Application: A gene with a low LoF constraint score is a stronger candidate for harboring pathogenic variants contributing to POI. For example, if your novel gene has an LoF oe score of 0.1 (pLI = 1.0), this strengthens the case that the rare variant you found may be deleterious.

What is the best way to resolve conflicting interpretations in ClinVar for a VUS in a POI gene?

It is common to find VUS with conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity in ClinVar.

- Problem: A FIGLA variant is listed as a VUS in your internal analysis, and ClinVar shows two submissions: one as "Likely pathogenic" and another as "Uncertain significance."

- Solution:

- Examine the Evidence: On the ClinVar VCV page, expand each submission to see the submitter's name, the date of last evaluation, and the evidence cited [46].

- Prioritize Expert-Reviewed Submissions: Favor submissions from reputable labs or consortia that provide detailed evidence and have a high review status (e.g., multiple stars) [46].

- Cross-reference with Population Data: Check the variant's frequency in gnomAD. If it is completely absent or very rare (

AF_popmax < 0.0001), it remains a candidate. If it is common, it is likely benign. - Use Parsing Tools: Leverage pipelines that parse ClinVar data to flag "conflicted" variants systematically, defined as those with both pathogenic and benign assertions [45].

Database Comparison & Key Metrics

Table 1: Core Features of gnomAD and ClinVar for POI Research

| Feature | gnomAD | ClinVar |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Catalog of population allele frequencies from control cohorts [44] | Archive of genotype-phenotype relationships and clinical interpretations [47] |

| Key Data Provided | Allele frequencies (global, per-population), constraint scores (pLI, missense Z), genotype quality metrics [44] | Pathogenicity assertions (Pathogenic, VUS, Benign), submitter information, review status, reported phenotypes [46] |

| Role in VUS Interpretation | Provides quantitative evidence to filter out common variants and assess gene intolerance [44] | Provides qualitative evidence from clinical testing and research, highlighting (in)consistency in interpretation [45] |

| Critical Field for POI | popmax AF (for filtering common variants); pLI (for gene-level candidacy) |

Review Status (to gauge confidence in an assertion); Conflicted flag (to identify discordance) [46] [45] |

Table 2: Essential gnomAD Metrics for Filtering in POI Research

| Metric | Description | Interpretation in POI Context |

|---|---|---|

| AF_popmax | The highest allele frequency observed in any specific population within gnomAD [43]. | Primary filter to remove common variants. Use AF_popmax < 0.01 (1%) for a rare disease like POI. |

| pLI | Probability of being loss-of-function intolerant. Range 0-1 [44]. | A high pLI (≥ 0.9) suggests the gene is sensitive to LoF variants, strengthening a candidate gene. |

| Filters | PASS vs. various failure codes (e.g., for sequencing artifacts) [48]. | Prioritize variants with a PASS filter status to avoid technical false positives. |

Experimental Protocol: Integrated Allele Frequency Workflow

This protocol outlines a standard methodology for leveraging gnomAD and ClinVar in the analysis of sequencing data from a POI cohort, as used in recent studies [16].

1. Input Data: VCF file from Next-Generation Sequencing (Whole Exome or Whole Genome) of POI patients [16].

2. Annotation: Annotate variants using a pipeline (e.g., VEP, SnpEff) that includes population frequency data from gnomAD and clinical interpretations from ClinVar.

3. Initial Filtering:

* Remove variants that do not have a PASS quality filter.

* Remove variants with a gnomAD AF_popmax > 0.01.

* Retain only exonic and splice-site variants.

4. Prioritization & Triage:

* Check remaining variants against ClinVar. Prioritize those with established Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic interpretations.

* For variants not in ClinVar or listed as VUS, analyze the gene-level constraint in gnomAD. Prioritize variants in genes with high pLI scores.

* For VUS, manually review the evidence on the ClinVar VCV page, paying close attention to conflicted status and review stars [46] [45].

5. Validation: Confirm prioritized variants (especially indels and CNVs) using an orthogonal method such as Sanger sequencing or array-CGH [16].

Integrated gnomAD and ClinVar Analysis Workflow for POI VUS Interpretation

Table 3: Essential Resources for Population Genomics in POI Research

| Resource / Reagent | Function in Analysis | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| gnomAD Browser | Primary interface for querying population allele frequencies and constraint scores [44]. | Use v2.1.1 for GRCh37 and v3.1.2 for GRCh38. Be mindful of sample overlap between versions [44]. |

| ClinVar VCV Page | Displays all data aggregated for a single variant, including submissions and review status [46]. | Critical for investigating conflicting interpretations and assessing the evidence behind a classification. |

| Custom Gene Panel | A targeted list of genes known or suspected to be involved in ovarian function [16]. | The 2025 POI study used a panel of 163 genes. Focuses analysis and increases depth of coverage. |

| ACMG/AMP Guidelines | A standardized framework for classifying variants based on evidence from population data, computational predictions, and functional data [49]. | Provides the criteria (e.g., PM2, BS1) for assigning Pathogenic, VUS, or Benign labels. |

| Variant Normalization Tool (e.g., vt normalize) | Standardizes variant representation to ensure consistent matching and annotation across databases [45]. | Prevents errors caused by non-minimal or left-aligned representations of complex variants. |

Frequently Asked Questions for POI Research

FAQ 1: Which in silico tools are most recommended for interpreting VUS in POI genes?

No single tool is perfect, and performance can vary. However, some tools consistently demonstrate high accuracy. For researchers beginning their analysis, a combination of the following tools is recommended:

- High-Performance Ensemble Tools: REVEL, BayesDel, and MutPred2 are meta-predictors that aggregate outputs from multiple other tools, often leading to more robust predictions [50] [51]. A 2025 study on CHD genes found BayesDel to be the most accurate score-based tool overall [51].

- Emerging AI-Based Tools: AlphaMissense shows significant promise. It is an AI model trained on human and primate variant population frequency databases and has been shown to outperform many established tools in initial validations [50] [51]. In a study on a CHEK1 VUS in POI, AlphaMissense provided a high pathogenicity score (0.754), which supported further investigation [15].

- Commonly Used Tools: SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and CADD are widely used and integrated into many analysis pipelines. A 2025 benchmark found SIFT to be the most sensitive tool for categorically classifying pathogenic variants in a specific gene family [51].

Table 1: Summary of Key In Silico Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Key Principle | Strengths in POI Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| REVEL [50] | Ensemble/Meta-predictor | Random forest classifier integrating scores from multiple tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, etc.) | High performance in benchmarking studies; useful for a broad range of variants. |

| AlphaMissense [50] [15] | AI/Deep Learning | Fine-tuned from AlphaFold; uses protein structure and evolutionary context. | High accuracy for rare variants; provides genome-wide predictions. |

| BayesDel [50] [51] | Ensemble/Meta-predictor | Native Bayes classifier trained on ClinVar and HGMD data (without allele frequency). | Identified as a top-performing tool for predicting pathogenicity in specific gene families. |

| MutPred2 [50] | Machine Learning | Deep neural network incorporating protein structural and functional data. | Provides hypotheses on molecular mechanisms of pathogenicity. |

| CADD [50] | Heuristic/Integration | Integrates diverse annotations but not trained on a specific disease variant set. | Widely used; can predict pathogenicity of variants not seen in training sets. |

| SIFT [51] | Sequence Homology-Based | Predicts effect based on sequence conservation across species. | High sensitivity; useful for initial filtering of deleterious variants. |

FAQ 2: I have conflicting predictions from different tools for my POI-related VUS. How should I proceed?

Conflicting predictions are common and highlight the need for a structured, multi-step approach.

- Consensus Check: Use a tool that generates a consensus from multiple predictors, such as REVEL or BayesDel [50]. A higher number of tools agreeing on a prediction increases confidence.

- Gene-Specific Validation: Be aware that tool performance can be gene-specific. A tool's overall high accuracy does not guarantee equal performance for all genes [50]. Consult the literature to see if validation has been performed for your gene of interest (e.g., a 2023 large-scale POI study identified genes where specific biological processes like meiosis are enriched) [26].