From Association to Function: A Research Framework for Experimental Validation of Non-Coding Endometriosis Variants

Endometriosis is a complex gynecological disorder with a significant heritable component, for which genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have predominantly identified risk variants in non-coding genomic regions.

From Association to Function: A Research Framework for Experimental Validation of Non-Coding Endometriosis Variants

Abstract

Endometriosis is a complex gynecological disorder with a significant heritable component, for which genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have predominantly identified risk variants in non-coding genomic regions. This creates a critical translational gap between statistical association and biological understanding. This article provides a comprehensive methodological roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to bridge this gap. We synthesize current strategies for identifying and prioritizing non-coding variants, detail state-of-the-art functional genomics and molecular techniques for their experimental validation, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present robust frameworks for validating findings and assessing their clinical potential. By integrating insights from recent GWAS, expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analyses, and non-coding RNA biology, this review serves as a strategic guide for elucidating the mechanistic role of non-coding variants in endometriosis pathogenesis, ultimately paving the way for novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Mapping the Non-Coding Landscape: Prioritizing Endometriosis Risk Variants for Functional Study

Leveraging GWAS Meta-Analyses to Identify Robust Non-Coding Risk Loci

Endometriosis is a common, heritable gynecological disorder estimated to affect 6-10% of women of reproductive age and is a major cause of chronic pelvic pain and infertility [1] [2]. With an estimated heritability of approximately 51%, understanding the genetic architecture of this condition has been a major focus of research [1]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have revolutionized the identification of common genetic variants contributing to endometriosis risk, yet a significant challenge remains: the majority of associated variants reside in non-coding genomic regions [3] [4]. This article examines how GWAS meta-analysis approaches have enabled the discovery of robust non-coding risk loci for endometriosis and outlines experimental frameworks for their functional validation, providing crucial insights for researchers and drug development professionals investigating this complex condition.

GWAS Meta-Analysis: Unlocking Statistical Power for Locus Discovery

The Evolution of Endometriosis GWAS

Initial GWAS for endometriosis conducted in individual populations faced limitations in statistical power to detect variants with modest effects. The pioneering Japanese GWAS identified the first genome-wide significant locus in CDKN2B-AS1 (rs10965235), while the first European-ancestry study revealed an intergenic locus on chromosome 7p15.2 (rs12700667) [5]. However, these early studies highlighted a critical challenge: many genuine associations remained hidden due to insufficient sample sizes and the stringent statistical thresholds required for genome-wide significance [6].

The strategic solution emerged through large-scale meta-analysis, which combines summary statistics from multiple GWAS datasets to dramatically increase sample size and statistical power. This approach proved particularly valuable for endometriosis, where heterogeneous case definitions and phenotypic classifications further complicated genetic discovery [5].

Landmark Meta-Analyses and Key Discoveries

Table 1: Key Endometriosis GWAS Meta-Analyses and Their Discoveries

| Study Description | Sample Size (Cases/Controls) | Ancestries | Novel Loci Identified | Key Genes Implicated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial multi-ancestry meta-analysis [1] | 4,604/9,393 | Japanese and European | 3 | WNT4, GREB1, VEZT |

| Expanded meta-analysis [2] | 17,045/191,596 | European and Japanese | 5 | FN1, CCDC170, ESR1, SYNE1, FSHB |

| Focus on severe disease [5] | 11,506/32,678 | European and Japanese | 2 (Stage III/IV) | FN1, novel 2p14 locus |

The transformative impact of meta-analysis is exemplified by a 2012 study that combined data from Australian, UK, and Japanese cohorts (4,604 cases and 9,393 controls). This analysis not only replicated previously reported associations at 7p15.2 (rs12700667) and 1p36.12 near WNT4 (rs7521902), but also identified three novel loci: 2p25.1 in GREB1 (rs13394619), 12q22 near VEZT (rs10859871), and additional loci when focusing on European cases with more severe disease [1].

A subsequent 2017 meta-analysis representing an approximate five-fold increase in effective sample size (17,045 cases and 191,596 controls) identified five additional novel loci highlighting genes involved in sex steroid hormone pathways: FN1, CCDC170, ESR1, SYNE1, and FSHB [2]. Remarkably, this study demonstrated that 19 independent SNPs together explained up to 5.19% of the variance in endometriosis risk [2].

From Association to Function: Validating Non-Coding Risk Loci

The Challenge of Non-Coding Variants

A critical insight from endometriosis GWAS is that approximately 88% of identified risk SNPs reside in non-coding regions, primarily in intergenic (43%) or intronic (45%) locations [5]. This distribution mirrors patterns observed for other complex traits and presents a fundamental challenge: determining the functional mechanisms by which these variants influence disease risk. The ENCODE project has revealed that approximately 80% of non-coding regions likely possess regulatory functionality, suggesting that non-coding risk variants likely exert their effects through modulating gene expression rather than altering protein structure [5].

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) Mapping

Table 2: Primary Experimental Methods for Validating Non-Coding Risk Loci

| Method | Key Application | Data Sources | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| eQTL Analysis | Links risk variants to gene expression | GTEx database, disease-relevant tissues | Slope (effect size/direction), FDR-adjusted p-value |

| Functional Annotation | Characterizes variant genomic context | Ensembl VEP, chromatin states | Variant location, regulatory marks, conservation |

| Pathway Enrichment | Identifies biological processes | MSigDB, Cancer Hallmarks | Enrichment p-values, false discovery rates |

| LD-based Clumping | Identifies independent signals | 1000 Genomes reference panels | Clump boundaries, index SNPs, r² values |

A powerful strategy for functional validation involves integrating GWAS findings with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data, which reveals how genetic variants influence gene expression in specific tissues. A 2025 study systematically analyzed 465 endometriosis-associated variants across six biologically relevant tissues: uterus, ovary, vagina, sigmoid colon, ileum, and peripheral blood [3]. This approach demonstrated striking tissue-specific regulatory patterns: immune and epithelial signaling genes predominated in intestinal tissues and blood, while reproductive tissues showed enrichment for genes involved in hormonal response, tissue remodeling, and adhesion [3].

The study identified key regulatory genes including MICB, CLDN23, and GATA4, which were consistently linked to critical pathways such as immune evasion, angiogenesis, and proliferative signaling [3]. The slope value (indicating direction and magnitude of regulatory effect) served as a key metric, with even moderate values (±0.5) representing potentially meaningful biological effects in disease-relevant contexts [3].

Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) Clumping for Signal Refinement

LD clumping is an essential bioinformatic method that distinguishes independent association signals from correlated variants. This technique uses the PLINK clumping algorithm to prune SNPs in linkage disequilibrium within a defined genomic window, retaining the variant with the lowest p-value [7]. Critical parameters include:

- clump_kb: Genetic distance window (default = 10,000kb)

- clump_r2: LD threshold (recently changed from 0.01 to 0.001)

- pop: Reference population for LD estimation (EUR, SAS, EAS, AFR, AMR) [7]

This method reduces multiple testing burden by grouping correlated SNPs into "clumps" representing independent signals, significantly enhancing the interpretability of GWAS results [6].

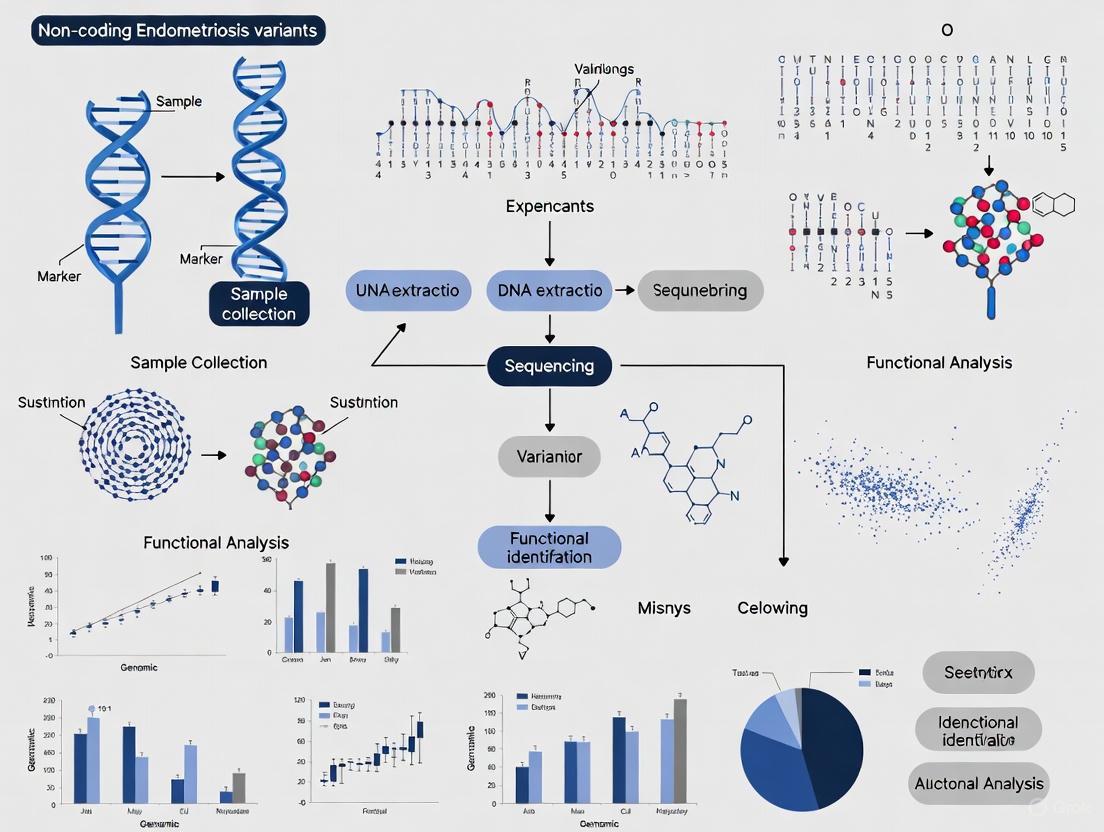

Visualizing the Research Pipeline

Endometriosis Risk Loci Discovery and Validation Workflow

Tissue-Specific Regulatory Mechanisms of Endometriosis Risk Variants

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Endometriosis Genetic Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS Data Repositories | GWAS Catalog [8], NHGRI-EBI Catalog | Variant-disease associations | Curated genome-wide associations, standardized annotations |

| LD Reference Panels | 1000 Genomes Project, OpenGWAS API [7] | Population-specific LD estimation | Super-population panels (EUR, SAS, EAS, AFR, AMR) |

| eQTL Databases | GTEx Portal v8 [3] | Tissue-specific expression regulation | Multi-tissue normalized effect sizes (slopes), FDR values |

| Functional Annotation | Ensembl VEP [3], ENCODE | Variant consequence prediction | Genomic context, regulatory elements, conservation |

| Analysis Tools | PLINK [6], TwoSampleMR [7], STAAR [9] | Statistical genetics analyses | LD clumping, Mendelian randomization, rare variant association |

| Pathway Resources | MSigDB Hallmark Gene Sets, Cancer Hallmarks [3] | Biological interpretation | Curated gene sets, functional enrichment |

Discussion and Future Directions

The integration of large-scale GWAS meta-analyses with functional genomics approaches has fundamentally advanced our understanding of endometriosis genetics. The remarkable consistency observed across diverse populations [5] underscores the robustness of these findings and provides a solid foundation for translational applications. Several critical insights have emerged from these efforts:

First, the tissue-specific nature of regulatory effects necessitates careful selection of biologically relevant tissues for functional studies [3]. The 2025 analysis demonstrated distinct regulatory profiles across reproductive versus intestinal and immune tissues, suggesting different mechanistic pathways may operate in different anatomical contexts.

Second, the stronger genetic effects observed for moderate-to-severe (rAFS Stage III/IV) endometriosis [1] [2] [5] indicate that genetic studies benefit from refined phenotypic classifications. This suggests that different genetic architectures may underlie disease subtypes, with implications for patient stratification in clinical trials and targeted therapies.

For drug development professionals, the identification of non-coding risk loci presents both challenges and opportunities. While these variants do not directly point to druggable protein targets, they illuminate key regulatory pathways and master regulator genes that may represent therapeutic intervention points. The implication of genes involved in sex steroid hormone signaling (ESR1, FSHB, WNT4) [2] and developmental pathways provides a molecular basis for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel treatment strategies.

Future research directions should include expanded multi-omics integration, development of tissue-specific regulatory maps, and functional characterization of candidate causal variants using genome editing technologies. As functional genomics resources continue to expand, particularly for diverse ancestral populations, our ability to interpret non-coding risk loci and translate these findings into clinical applications will accelerate significantly.

Integrating eQTL Data to Link Variants to Target Genes and Tissues

Endometriosis, a chronic inflammatory condition affecting millions globally, is known to have a significant genetic component. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified numerous genetic variants associated with endometriosis risk. However, a critical challenge remains: the majority of these disease-associated variants reside in non-coding regions of the genome, making their functional interpretation and linkage to target genes particularly challenging [3]. This gap hinders the translation of genetic discoveries into actionable biological insights and therapeutic targets.

Expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analysis has emerged as a powerful computational bridge, connecting statistical genetic associations with functional molecular mechanisms. eQTLs are genetic variations associated with the expression levels of specific genes, effectively identifying genomic loci that regulate gene expression [10]. By mapping how genetic variants influence gene expression in specific tissues, eQTL analysis provides a direct mechanistic hypothesis for how non-coding variants might contribute to disease pathogenesis by altering the expression of key genes.

This guide objectively compares the application of different eQTL integration strategies within the context of endometriosis research. We evaluate established and emerging methodologies based on their ability to pinpoint causal genes, resolve tissue-specific effects, and ultimately advance the experimental validation of non-coding variants in this complex disease.

Comparative Analysis of eQTL Integration Methods

The integration of eQTL data with GWAS findings can be approached through various methodologies, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases. The table below provides a structured comparison of the primary strategies used in endometriosis research.

Table 1: Comparison of eQTL Integration Methodologies for Endometriosis Research

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Supporting Data from Endometriosis Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue-Specific eQTL Mapping | Identifies gene-variant associations within specific, disease-relevant tissues (e.g., uterus, ovary) using resources like GTEx [3]. | - Reveals biologically relevant regulatory contexts.- Identifies tissue-specific therapeutic targets.- Uses widely available public data. | - Limited by tissue availability in public banks.- May miss systemic immune or inflammatory effects. | Analysis of 465 endometriosis-associated variants across 6 tissues found distinct regulatory profiles: immune genes in colon/ileum/blood vs. hormonal response genes in reproductive tissues [3]. |

| Mendelian Randomization (MR) with eQTL | Uses eQTLs as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships between gene expression and disease risk [11]. | - Provides evidence for causal inference, not just correlation.- Reduces confounding.- Useful for prioritizing candidate genes. | - Requires strong genetic instruments.- Sensitive to pleiotropy.- Complex interpretation. | A study on breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) integrated MR with GEO data, identifying 13 candidate genes like PTPN12 and GPX3, later validated by functional assays [11]. |

| Single-Cell eQTL Mapping | Maps genetic variants to gene expression within individual cell types from complex tissues (e.g., PBMCs) using scRNA-seq [12]. | - Unprecedented resolution of cell-type-specific regulation.- Identifies effects masked in bulk tissue.- Reveals regulation in rare cell populations. | - Computationally intensive and costly.- Lower statistical power per cell type.- Complex data processing. | A study of human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) in PBMCs identified 3,463 conditionally independent eQTLs, revealing cell-type-specific genetic regulation of retroviral elements linked to autoimmunity [12]. |

| reg-eQTL (Advanced Method) | Incorporates Transcription Factor (TF) effects and TF-SNV interactions into the eQTL model to identify causal trios (SNV, TF, Target Gene) [13]. | - Pinpoints potential causal variants and mechanisms.- Detects low-frequency/weak-effect variants.- Builds mechanistic regulatory networks. | - Method is novel, with limited large-scale application.- Dependent on accurate TF binding annotations. | Application to GTEx data uncovered novel eQTLs and shared regulation across lung, brain, and blood tissues, providing deeper mechanistic insights than traditional methods [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

The integration of eQTL data generates hypotheses that require rigorous experimental validation. The following protocols detail key methodologies cited in comparative studies.

Protocol 1: Functional Validation of Candidate Genes Using Transwell Invasion Assay

This cell-based protocol was used to validate the functional role of eQTL-prioritized genes (PTPN12, YTHDC2, MAPKAPK3, GPX3, RASA3, TSPAN4) in the context of breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) invasion, a relevant model for understanding progression [11].

- Objective: To determine if silencing or overexpressing eQTL-identified genes directly impacts cell invasive capability.

- Materials:

- DCIS cell line.

- Transwell chambers with Matrigel-coated membranes.

- Procedure:

- Gene Modulation: Perform siRNA-mediated silencing of candidate genes (

PTPN12,YTHDC2,MAPKAPK3) or plasmid-based overexpression (GPX3,RASA3,TSPAN4) in DCIS cells. - Cell Seeding: Seed transfected cells into the upper chamber of the Transwell insert in serum-free medium.

- Induce Invasion: Place complete growth medium (chemoattractant) in the lower chamber and incubate for 24-48 hours.

- Fix and Stain: Remove non-invaded cells from the upper chamber surface. Fix and stain the invaded cells on the lower membrane surface.

- Quantification: Count the stained, invaded cells under a microscope across multiple fields. Compare invasion counts between experimental (silenced/overexpressed) and control groups.

- Gene Modulation: Perform siRNA-mediated silencing of candidate genes (

- Supporting Data: The study confirmed that silencing

PTPN12,YTHDC2, andMAPKAPK3, or overexpressingGPX3,RASA3, andTSPAN4, significantly suppressed DCIS cell invasion, functionally validating their role in progression [11].

Protocol 2: Tissue-Specific eQTL Analysis Pipeline for Endometriosis Variants

This bioinformatics protocol outlines the steps for functionally characterizing endometriosis-associated GWAS variants via eQTL analysis in relevant tissues [3].

- Objective: To identify the target genes and tissues through which endometriosis-associated non-coding variants exert their regulatory effects.

- Materials:

- List of genome-wide significant endometriosis-associated variants (e.g., from GWAS Catalog).

- Tissue-specific eQTL data from GTEx portal (v8).

- Computational resources (R, Python) for data analysis.

- Procedure:

- Variant Curation: Retrieve and filter endometriosis-associated variants (p < 5x10-8) from the GWAS Catalog, ensuring valid rsIDs.

- Functional Annotation: Use the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) to determine the genomic location (intronic, intergenic, etc.) of each variant.

- eQTL Mapping: Cross-reference the variant list with GTEx data across six biologically relevant tissues: uterus, ovary, vagina, sigmoid colon, ileum, and whole blood.

- Filter Significant eQTLs: Retain only variant-gene pairs with a significant false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05.

- Prioritize Candidate Genes: Prioritize genes based on (i) the number of associated variants and (ii) the magnitude of the regulatory effect (slope value from GTEx).

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Input the prioritized gene lists into pathway analysis tools (e.g., MSigDB Hallmark, Cancer Hallmarks) to identify overrepresented biological pathways.

- Supporting Data: Application of this pipeline revealed tissue-specificity; for instance, genes like

MICB,CLDN23, andGATA4were consistently linked to immune evasion, angiogenesis, and proliferative signaling pathways [3].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Regulatory Mechanisms

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate the core workflows and mechanistic relationships described in this guide.

eQTL Integration and Validation Workflow

Diagram Title: Endometriosis eQTL Integration Workflow

reg-eQTL Regulatory Trio Mechanism

Diagram Title: reg-eQTL Trio Mechanism

Successfully linking non-coding variants to target genes requires a suite of specialized data resources, analytical tools, and experimental reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for eQTL-Guided Endometriosis Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GTEx Portal | Data Resource | Provides a public repository of tissue-specific eQTLs from healthy individuals, establishing baseline regulatory landscapes [3]. | Used to map 465 endometriosis GWAS variants, revealing constitutive regulatory effects in uterus, ovary, and blood [3]. |

| Ensembl VEP | Software Tool | Functionally annotates genetic variants, predicting their location and potential impact on genes, a critical first step after GWAS [3]. | Annotated non-coding endometriosis variants, confirming their enrichment in regulatory regions prior to eQTL analysis [3]. |

| GWAS Catalog | Data Resource | A curated collection of all published GWAS and their associated variants, allowing for the systematic retrieval of trait-associated SNPs [3]. | Served as the source for 465 unique, genome-wide significant endometriosis variants for downstream eQTL analysis [3]. |

| reg-eQTL Algorithm | Software Tool | A novel method that incorporates transcription factor effects and interactions to identify causal regulatory trios (SNV, TF, Target Gene) [13]. | Applied to GTEx data, it uncovered novel eQTLs and shared regulatory networks across tissues, offering deeper mechanistic insight [13]. |

| Transwell Invasion Assay | Laboratory Reagent | A standardized in vitro system to quantitatively measure the invasive potential of cells after genetic manipulation [11]. | Provided functional validation that eQTL-prioritized genes (PTPN12, GPX3, etc.) directly influence cellular invasion [11]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq | Technology | Profiles gene expression at the level of individual cells, enabling the discovery of cell-type-specific eQTLs masked in bulk tissue [12]. | Used on PBMCs to map eQTLs for human endogenous retroviruses, revealing cell-type-specific genetic regulation in immunity [12]. |

Endometriosis, a chronic gynecological disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity, affects approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women worldwide and represents a significant challenge in women's health [14] [15]. The disease manifests through heterogeneous symptoms including chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and reduced fertility, often leading to delayed diagnosis of 6-12 years due to the lack of reliable non-invasive diagnostic methods [15] [16]. The gold standard for diagnosis remains laparoscopic surgery, an invasive procedure that underscores the urgent need for molecular biomarkers [17] [18]. Within this context, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—particularly microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)—have emerged as crucial regulators of gene expression in endometriosis pathogenesis, offering promising avenues for diagnostic and therapeutic development [19] [18].

The broader thesis of experimental validation for non-coding endometriosis variants centers on translating ncRNA research into clinical applications. This involves systematic efforts to identify dysregulated ncRNAs, validate their functional roles in disease mechanisms, and develop them into reliable biomarkers or therapeutic targets. Current research indicates that ncRNAs contribute to endometriosis through diverse mechanisms including epigenetic regulation, control of inflammatory responses, cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling [14] [19]. This review comprehensively compares the roles of lncRNAs and miRNAs in endometriosis, providing experimental data, methodological protocols, and analytical frameworks to advance their validation as clinically relevant molecules.

Biogenesis and Functional Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis

miRNA Biogenesis and Regulatory Functions

MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules approximately 22-25 nucleotides in length that function as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression [15]. Their biogenesis begins with RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription of primary miRNA transcripts (pri-miRNAs) in the nucleus [17]. These pri-miRNAs are processed by the microprocessor complex, comprising the RNase III enzyme Drosha and its cofactor DGCR8, to produce precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) of approximately 60-70 nucleotides [18] [20]. Exportin-5 then transports pre-miRNAs to the cytoplasm, where Dicer, another RNase III enzyme, cleaves them into mature miRNA duplexes [17] [20]. The functional strand of this duplex is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which includes Argonaute (AGO2) proteins, and guides the complex to complementary mRNA targets [18] [20]. miRNA binding typically occurs at the 3'-untranslated regions (3'-UTRs) of target mRNAs, resulting in translational repression or mRNA degradation [15] [17]. Individual miRNAs can regulate numerous mRNA targets, with estimates suggesting that miRNAs collectively regulate up to 60% of human genes [16].

lncRNA Biogenesis and Multifunctional Roles

Long non-coding RNAs are defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that lack significant protein-coding potential [14]. The GENCODE project has annotated approximately 17,958 lncRNA genes in the human genome, though some studies suggest the total number may exceed 100,000 [14] [19]. Unlike miRNAs, lncRNAs exhibit complex secondary and tertiary structures that enable diverse molecular functions [14]. They can localize to specific cellular compartments—either nuclear or cytoplasmic—where they employ varied mechanisms of action. In the nucleus, lncRNAs function as epigenetic regulators by recruiting chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci, either in cis (affecting nearby genes) or in trans (affecting distant genes) [14]. They can act as decoys by sequestering transcription factors or chromatin modifiers, thereby preventing their binding to target genes [14]. Additionally, nuclear lncRNAs can influence alternative splicing patterns of pre-mRNAs [14]. In the cytoplasm, lncRNAs participate in post-transcriptional regulation by affecting mRNA stability, modulating translation, or serving as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) that "sponge" miRNAs and prevent them from binding their mRNA targets [14] [19]. This ceRNA function creates intricate regulatory networks between lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs, adding a layer of complexity to gene regulation in endometriosis [14].

Table 1: Comparative Features of miRNAs and lncRNAs in Endometriosis

| Feature | miRNAs | lncRNAs |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 18-25 nucleotides [17] | >200 nucleotides [14] |

| Genomic Abundance | ~2,600 mature miRNAs in humans [15] | ~17,958 annotated genes (possibly >100,000) [14] [19] |

| Primary Functions | Post-transcriptional repression via mRNA degradation/translational inhibition [15] [17] | Epigenetic regulation, transcriptional control, molecular scaffolding, miRNA sponging [14] |

| Mechanisms in Endometriosis | miRNA-mRNA interactions; pathway modulation (PI3K/AKT, MAPK) [19] | Chromatin modification; ceRNA networks; signaling pathway regulation [14] [19] |

| Stability in Circulation | High stability in body fluids [17] | Detectable in serum/plasma [17] |

| Diagnostic Applications | Multi-miRNA panels with AUC up to 0.94 [19] [16] | Emerging biomarkers (e.g., UCA1) [19] |

Figure 1: Biogenesis and Functional Mechanisms of miRNAs and lncRNAs. miRNA processing involves sequential cleavage events in the nucleus and cytoplasm, resulting in mature miRNAs that guide RISC complexes to target mRNAs. lncRNAs are transcribed similarly to mRNAs but undergo different processing and can localize to nuclear or cytoplasmic compartments to perform diverse regulatory functions.

Experimental Approaches for ncRNA Analysis

Genome-Wide Profiling Technologies

Comprehensive analysis of ncRNAs in endometriosis employs high-throughput transcriptomic technologies that enable simultaneous examination of thousands of RNA molecules. For miRNA profiling, the most common approaches include small RNA sequencing and miRNA microarrays [15] [17]. Small RNA sequencing provides the advantage of detecting novel miRNAs and isomiRs (miRNA variants), while microarrays offer a cost-effective solution for focused screening of known miRNAs [17]. In a recent ENDO-miRNA study, researchers performed genome-wide miRNA expression profiling using next-generation sequencing (NGS) of plasma samples from 200 women with chronic pelvic pain, identifying a diagnostic signature for endometriosis [16]. The sequencing was conducted on a Novaseq 6000 platform with approximately 17 million single-end reads per sample, followed by alignment to reference databases using Bowtie and quantification with miRDeep2 [16].

For lncRNA analysis, RNA sequencing represents the primary discovery tool, as it can distinguish between coding and non-coding transcripts based on coding potential calculations [14]. Sun et al. employed this approach to identify 948 differentially expressed lncRNAs in ectopic endometrial tissues compared to paired eutopic endometrial tissues [19]. The experimental workflow typically includes ribosomal RNA depletion to enrich for non-coding transcripts, followed by library preparation and sequencing on platforms such as Illumina [14]. Microarray-based platforms specifically designed for lncRNAs provide an alternative when sequencing capacity is limited, though they are restricted to annotated transcripts [18].

Validation Methodologies

Following initial discovery, candidate ncRNAs require validation using targeted, quantitative methods. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) represents the gold standard for validation due to its sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative nature [17]. For miRNA analysis, this typically involves stem-loop reverse transcription primers that enhance specificity for mature miRNAs, followed by TaqMan or SYBR Green-based detection [17]. When designing qRT-PCR assays for lncRNAs, primers should span exon-exon junctions to minimize genomic DNA amplification [14].

In situ hybridization (ISH) provides spatial context to ncRNA expression patterns, allowing researchers to determine which cell types within heterogeneous endometrial tissues express specific ncRNAs [17]. For circRNA analysis, RNase R treatment is often incorporated to degrade linear RNAs and confirm circular structure [20]. Additional validation approaches include northern blotting for confirming ncRNA size and abundance, and nanostring nCounter technology for multiplexed analysis without amplification bias [17].

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for ncRNA Analysis in Endometriosis

| Method | Key Steps | Applications in Endometriosis | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small RNA Sequencing [16] | 1. RNA extraction from plasma/tissue2. Library prep with QIAseq miRNA Library Kit3. Sequencing on Illumina platform4. Alignment (Bowtie) and quantification (miRDeep2) | Genome-wide miRNA discovery; identification of diagnostic signatures | Detects novel miRNAs; requires bioinformatics expertise |

| RNA Sequencing [14] [19] | 1. rRNA depletion2. cDNA library preparation3. High-throughput sequencing4. Differential expression analysis (DESeq2) | Identification of differentially expressed lncRNAs; pathway analysis | Distinguishes coding/non-coding transcripts; covers entire transcriptome |

| qRT-PCR Validation [17] | 1. RNA extraction (Maxwell RSC system)2. Reverse transcription (stem-loop for miRNA)3. Quantitative PCR with specific primers4. Data normalization (using snoRNAs/snRNAs) | Validation of candidate ncRNAs; independent cohort analysis | Gold standard for validation; requires appropriate normalization |

| In Situ Hybridization [17] | 1. Tissue fixation and sectioning2. Probe design and labeling3. Hybridization and signal detection4. Counterstaining and microscopy | Spatial localization of ncRNAs in endometrial tissues | Preserves tissue architecture; technically challenging |

| Microarray Analysis [15] [18] | 1. RNA extraction and quality control2. Fluorescent labeling3. Hybridization to miRNA/lncRNA arrays4. Scanning and data analysis | Expression profiling of known ncRNAs; cohort comparisons | Cost-effective for focused studies; limited to annotated transcripts |

Signaling Pathways Regulated by ncRNAs in Endometriosis

Non-coding RNAs participate in intricate regulatory networks that control key signaling pathways implicated in endometriosis pathogenesis. Understanding these interactions provides insights into disease mechanisms and reveals potential therapeutic targets.

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, a critical regulator of cell survival and proliferation, is frequently dysregulated in endometriosis through ncRNA-mediated mechanisms [19]. For instance, miR-200b and miR-15a-5p have been identified as negative regulators of this pathway, with their downregulation in endometriotic tissues contributing to enhanced cell survival and proliferation [19]. Conversely, lncRNA DLEU1 has been shown to promote mTOR signaling, creating a balance between miRNA and lncRNA influences on this crucial pathway [21].

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, involved in cell fate determination and proliferation, is similarly modulated by ncRNAs. LncRNA H19, which is upregulated in endometriosis, enhances Wnt signaling by acting as a competitive sponge for let-7 miRNA family members, thereby increasing the expression of their target genes [21]. This mechanism illustrates the complex ceRNA networks wherein lncRNAs sequester miRNAs to prevent them from repressing their mRNA targets. Additionally, lncRNA NEAT1 has been demonstrated to promote endometrial cancer cell proliferation through regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, suggesting similar functions may occur in endometriosis [21].

MAPK signaling pathways, including p38-MAPK and ERK1/2-MAPK, represent additional targets of ncRNA regulation in endometriosis [19]. These pathways transduce extracellular signals that influence cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. LncRNA MEG3-210 has been shown to regulate endometrial stromal cell migration, invasion, and apoptosis through p38 MAPK and PKA/SERCA2 signaling via interaction with Galectin-1 [21]. Similarly, multiple miRNAs have been identified that target components of MAPK signaling cascades, though their specific roles in endometriosis require further characterization.

Figure 2: ncRNA-Regulated Signaling Pathways in Endometriosis. miRNAs (yellow ellipses) and lncRNAs (green ellipses) form complex regulatory networks that modulate key signaling pathways involved in endometriosis pathogenesis. Solid arrows indicate activation or inhibition, while dashed arrows represent sponging interactions in ceRNA networks.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

ncRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers

The strong association between specific ncRNA expression patterns and endometriosis has positioned them as promising candidates for non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers. Blood-based miRNA signatures have demonstrated particularly impressive diagnostic performance. Moustafa et al. identified a 6-miRNA signature (increased miR-125b-5p, miR-150-5p, miR-342-3p, and miR-451a; decreased miR-3613-5p and let-7b) that differentiated endometriosis patients from controls with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.94 [19] [16]. Similarly, the ENDO-miRNA study utilized artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches to develop a blood-based miRNA signature with 96.8% sensitivity, 100% specificity, and an AUC of 98.4% for detecting endometriosis [16]. These performances suggest that miRNA-based tests could potentially replace diagnostic laparoscopy in the future.

LncRNAs show increasing promise as diagnostic biomarkers, though they are at an earlier stage of development. Huang et al. reported that serum levels of lncRNA UCA1 were elevated in patients with ovarian endometriosis and decreased following treatment [19]. Notably, serum UCA1 levels at discharge were significantly lower in patients without recurrence compared to those who experienced disease recurrence, suggesting potential utility as both a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker [19]. Other lncRNAs including H19, MALAT1, and MEG3 have shown differential expression in endometriosis patients versus controls, though their clinical validation requires larger studies [14] [21].

Table 3: Promising ncRNA Biomarkers for Endometriosis Diagnosis

| ncRNA | Expression Pattern | Sample Type | Diagnostic Performance | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-125b-5p | Upregulated | Serum | AUC: 0.92 (as part of 6-miRNA panel) | Moustafa et al. [19] |

| miR-150-5p | Upregulated | Serum | AUC: 0.68-0.92 (individual values) | Moustafa et al. [19] |

| miR-451a | Upregulated | Serum | Part of 6-miRNA signature (AUC: 0.94) | Moustafa et al. [19] |

| let-7b | Downregulated | Serum | Part of 6-miRNA signature (AUC: 0.94) | Moustafa et al. [19] |

| miR-122 | Upregulated | Serum | Sensitivity: 95.6%, Specificity: 91.4% | Maged et al. [19] |

| miR-199a | Upregulated | Serum | Sensitivity: 100%, Specificity: 100% | Maged et al. [19] |

| UCA1 | Upregulated | Serum | Higher in patients, decreased post-treatment | Huang et al. [19] |

| H19 | Upregulated | Tissue | Associated with stromal cell growth via IGF signaling | Ghazal et al. [21] |

Therapeutic Targeting of ncRNAs

Beyond diagnostic applications, ncRNAs represent promising therapeutic targets for endometriosis treatment. Several strategies have emerged for modulating ncRNA activity, including anti-miRNA oligonucleotides (AMOs) that silence overexpressed miRNAs, and miRNA mimics to restore the function of downregulated tumor-suppressor miRNAs [20]. These approaches typically utilize chemically modified nucleotides (e.g., 2'-O-methyl, 2'-O-methoxyethyl, or locked nucleic acid [LNA] modifications) to enhance stability and binding affinity while reducing immunogenicity [22] [20].

For lncRNA targeting, multiple strategies are being explored. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) can be designed to degrade specific lncRNAs [22] [20]. Alternatively, lncRNA promoter-targeting approaches using CRISPR/Cas9 systems or small molecules can transcriptionally suppress lncRNA expression [20]. The efficacy of lncRNA targeting was demonstrated in a study where knockdown of lncRNA PCAT1 suppressed endometriosis stem cell proliferation and invasion by restoring miR-145-mediated regulation of target genes including FASCIN1, SOX2, and SERPINE1 [14].

A significant challenge in therapeutic ncRNA targeting is delivery to specific tissues. Current research focuses on nanoparticle-based delivery systems that protect oligonucleotides from degradation and enhance their accumulation in target tissues [20]. Lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, and exosome-based delivery systems show particular promise for delivering ncRNA-targeting therapeutics to endometrial and endometriotic tissues [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ncRNA Studies in Endometriosis

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Maxwell RSC miRNA Plasma/Serum Kit [16] | Isolation of high-quality RNA from biofluids | Automated extraction reduces variability; maintains miRNA integrity |

| Library Prep Kits | QIAseq miRNA Library Kit (Illumina) [16] | Small RNA sequencing library preparation | Includes unique molecular identifiers for accurate quantification |

| qRT-PCR Assays | TaqMan MicroRNA Assays [17] | Specific detection of mature miRNAs | Stem-loop RT primers enhance specificity for mature miRNAs |

| Normalization Controls | snoRNAs (e.g., RNU44, RNU48) [17] | Reference genes for qRT-PCR data normalization | Stable expression across menstrual cycle and disease states |

| ISH Probes | LNA-modified probes [17] | Spatial localization of ncRNAs in tissues | Enhanced binding affinity and specificity |

| Cell Culture Models | Endometrial stromal cells (ESCs) [19] | Functional validation of ncRNA targets | Primary cells maintain physiological relevance |

| Transfection Reagents | Lipid-based nanoparticles [20] | Delivery of miRNA mimics/inhibitors | Optimized for primary endometrial cells |

| Animal Models | Rodent endometriosis models [14] | In vivo functional studies | Immunocompromised mice for xenograft studies |

| 1,2,4-Trimethoxy-5-nitrobenzene | 1,2,4-Trimethoxy-5-nitrobenzene, CAS:14227-14-6, MF:C9H11NO5, MW:213.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-Nitrodiazoaminobenzene | 4-Nitrodiazoaminobenzene | High-Purity Research Chemical | High-purity 4-Nitrodiazoaminobenzene for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The comprehensive comparison of lncRNA and miRNA studies in endometriosis reveals both distinct and complementary roles for these ncRNA classes in disease pathogenesis. miRNAs function primarily as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression through direct targeting of mRNAs, while lncRNAs employ more diverse mechanisms including chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, and miRNA sponging. From a diagnostic perspective, miRNA signatures currently show superior performance characteristics, with several multi-miRNA panels achieving AUC values >0.9 for detecting endometriosis from blood samples [19] [16]. However, lncRNAs offer unique insights into disease mechanisms and show promise as prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

The experimental validation of non-coding RNA variants in endometriosis continues to face several challenges. The heterogeneity of endometriosis lesions and variations across menstrual cycle phases necessitate careful study design and appropriate normalization strategies [17]. Furthermore, the complex ceRNA networks involving cross-regulation between lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs require sophisticated experimental approaches to disentangle [14]. Future research directions should include larger validation cohorts, standardized protocols for ncRNA quantification, and development of more sophisticated animal models that recapitulate the human disease.

From a therapeutic perspective, ncRNA-based treatments for endometriosis remain in early developmental stages compared to other fields such as oncology. However, the rapid advances in oligonucleotide chemistry and targeted delivery systems provide optimism that ncRNA-targeting therapies may eventually benefit endometriosis patients [22] [20]. The continued integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches, as demonstrated in the ENDO-miRNA study, will likely accelerate the identification of robust ncRNA signatures and therapeutic targets [16]. As these technologies mature and our understanding of ncRNA biology in endometriosis deepens, the translation of ncRNA research into clinical applications represents a promising frontier for improving the diagnosis and management of this challenging condition.

Annotating Functional Potential with Specialized Databases (NCAD, GREEN-DB)

The application of whole genome sequencing (WGS) in clinical diagnostics has revealed that non-coding variants play a significant role in penetrant diseases, including endometriosis [23]. Endometriosis, a chronic, estrogen-dependent inflammatory disorder affecting 10-15% of women of reproductive age, demonstrates a complex genetic architecture where non-coding variants may contribute substantially to disease pathogenesis [24]. Current evidence suggests a polygenic and multifactorial inheritance pattern wherein disease development results from a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental influences [25]. However, the interpretation of non-coding variants remains a significant challenge due to the complex functional regulatory mechanisms of non-coding regions and limitations in available databases and tools [26] [23].

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines have historically focused on coding regions, resulting in under-interpretation of non-coding variants [26]. Among the 43,473 pathogenic variants of high-confidence cataloged by the ClinVar database, only 901 (2.07%) variants have been pinpointed within non-coding regions (excluding canonical splicing variants) [26]. This discrepancy highlights the urgent need for specialized databases and annotation frameworks to decipher the functional potential of non-coding variants in endometriosis and other complex genetic disorders.

Database Architectures and Functional Annotation Mechanisms

NCAD: A Comprehensive Non-Coding Variant Annotation Database

The Non-Coding Variant Annotation Database (NCAD) v1.0 represents a wide-ranging database that provides an intuitive graphical interface for online retrieval and offline annotation of essential evidence required for clinical genetic testing [26]. NCAD amalgamated data from 96 distinct sources, totaling up to 6 TB, categorized into three sections: Variants, Regulatory elements, and Element interactions [26] [23]. This comprehensive platform specifically designed for annotating and interpreting non-coding variants integrates crucial information including population frequencies of 12 diverse populations, 12 prediction scores for variant functionality and pathogenicity, five categories of regulatory elements, four types of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), histone modification, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, and three types of element interactions [26].

Notably, NCAD v1.0 encompasses comprehensive insights into 665,679,194 variants, regulatory elements, and element interaction details, providing vital information to support the genetic diagnosis of non-coding variants [23]. A particular strength is its inclusion of population frequency information for 230,235,698 variants in 20,964 Chinese individuals, addressing population-specific variation that may be relevant in diverse patient populations [23]. The database seamlessly integrates data spanning both GRCh37 and GRCh38 genome versions, enhancing its utility for researchers working with different genomic builds [23].

GREEN-DB: A Framework for Regulatory Variant Annotation

GREEN-DB (Genomic Regulatory Elements ENcyclopedia Database) presents a comprehensive framework for the prioritization of non-coding regulatory variants that integrates information about regulatory regions with prediction scores and HPO-based prioritization [27]. The database comprises a collection of approximately 2.4 million regulatory elements annotated with controlled gene(s), tissue(s) and associated phenotype(s) where available [27]. This framework addresses the critical challenge of programmatic annotation of regulatory variants and their respective target gene(s), which has been lacking despite the increasing adoption of WGS over whole-exome sequencing (WES) in disease studies [27].

The GREEN-DB framework incorporates several innovative features, including a variation constraint metric for regulatory regions. This analysis revealed that constrained regulatory regions associate with disease-associated genes and essential genes from mouse knock-outs, providing valuable prioritization criteria [27]. Additionally, the developers conducted a comprehensive evaluation of 19 non-coding impact prediction scores, providing evidence-based suggestions for variant prioritization within their framework [27]. The accompanying annotation tool, GREEN-VARAN, processes standard variant call format (VCF) files and generates comprehensive annotations of non-coding variants, ranking them from Level 1 to Level 4 based on supporting evidence [27].

Table 1: Core Database Architectures and Annotation Capabilities

| Feature | NCAD | GREEN-DB |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Non-coding variant annotation and interpretation | Regulatory variant annotation and prioritization |

| Data Sources | 96 distinct sources [26] | 16 primary sources plus additional functional datasets [27] |

| Variant Coverage | 665,679,194 variants [23] | Framework for analyzing variants in ~2.4M regulatory elements [27] |

| Population Data | 12 diverse populations, including 20,964 Chinese individuals [23] | Integrated gnomAD allele frequency data [27] |

| Prediction Scores | 12 scores for variant functionality and pathogenicity [26] | Evaluation of 19 non-coding impact prediction scores [27] |

| Regulatory Elements | 5 categories of regulatory elements, 4 types of ncRNAs [26] | Comprehensive collection of regulatory elements with gene/tissue annotations [27] |

| Genome Builds | GRCh37 and GRCh38 [23] | GRCh38 (with GRCh37 conversion available) [27] |

Performance Comparison in Non-Coding Variant Interpretation

Benchmarking Methodologies for Database Performance

Evaluating the performance of non-coding variant annotation databases requires specialized benchmarking approaches. A comprehensive review of tools for interpreting human non-coding variants established rigorous inclusion criteria, requiring tools to be freely available, accept VCF files as input, and be fully accessible with all additional datasets necessary for running the tool [28]. Performance assessment typically involves metrics such as the number of variants annotated, computational time, specificity (TN/[TN + FP]), precision (TP/[TP + FP]), sensitivity (TP/[TP + FN]), and accuracy ([TP + TN]/[TP + TN + FP + FN]) [28].

For benchmarking non-coding variant databases, researchers often employ a set of manually curated known pathogenic and benign NCVs from resources like ncVarDB, which includes 721 certainly pathogenic and 7,228 certainly benign NCVs spread over the whole human genome [28]. The computational resources required by the tools can be evaluated by merging known variant sets with variants from reference samples, such as the Han Chinese ancestry sample (HG005-NA24631) from the Genome In A Bottle (GIAB) project [28]. This approach allows comprehensive assessment of both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency.

Experimental Performance Data

Independent performance assessments reveal strengths and limitations of existing non-coding variant interpretation methods. A comprehensive evaluation of 24 computational methods for predicting the effects of variants in human non-coding sequences found that all tested methods performed differently under various conditions, indicating varying strengths and weaknesses under different scenarios [29]. Importantly, the performance of existing methods was acceptable for rare germline variants from ClinVar with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.4481–0.8033 but poor for rare somatic variants from COSMIC (AUROC = 0.4984–0.7131), common regulatory variants from curated eQTL data (AUROC = 0.4837–0.6472), and disease-associated common variants from curated GWAS (AUROC = 0.4766–0.5188) [29].

In the specific context of GREEN-DB, evaluation demonstrated that the database could capture previously published disease-associated non-coding variants. The GREEN-VARAN tool successfully mapped 40 out of 45 validated non-coding variants to the correct gene and classified 32 of these variants as likely to impact gene expression [26]. This performance highlights the potential of specialized databases to improve annotation accuracy for regulatory variants.

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Non-Coding Variant Interpretation

| Performance Metric | NCAD Performance | GREEN-DB Performance | Industry Benchmark (24 Tools) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rare Germline Variants (AUROC) | Not explicitly reported | Not explicitly reported | 0.4481–0.8033 [29] |

| Rare Somatic Variants (AUROC) | Not explicitly reported | Not explicitly reported | 0.4984–0.7131 [29] |

| Regulatory Variant Mapping | Not explicitly reported | 40/45 validated variants correctly mapped [26] | Not available |

| Impact Prediction Accuracy | Not explicitly reported | 32/45 variants classified as impact likely [26] | Not available |

| Computational Efficiency | Not explicitly reported | Not explicitly reported | Varies significantly by tool [28] |

Application in Endometriosis Research: Experimental Validation Protocols

In Silico Analysis of Estrogen-Related Genes in Endometriosis

The application of specialized non-coding annotation databases in endometriosis research follows structured experimental protocols. A recent study investigating the potential contribution of missense Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in the ESR1 (Estrogen Receptor 1) and GREB1 (Growth Regulation by Estrogen in Breast Cancer 1) genes to endometriosis pathogenesis employed a comprehensive in silico bioinformatics approach [25]. The methodology included retrieval of protein sequences and missense variants from NCBI and dbSNP databases, interaction analysis using STRING and GeneMANIA tools, and functional impact prediction using six bioinformatics tools: SIFT, PolyPhen-2, PROVEAN, PANTHER, SNPs&GO, and PredictSNP [25].

This experimental protocol identified ESR1 as a central node in estrogen signaling, with strong predicted interactions with GREB1 and other hormone-regulated genes. Several SNPs in both genes were consistently classified as deleterious across all predictive tools [25]. Disease enrichment analysis further linked these genes to endometriosis, as well as to other estrogen-responsive conditions such as breast and ovarian cancers [25]. This approach demonstrates how non-coding annotation databases can prioritize variants for functional validation in endometriosis research.

Workflow for Non-Coding Variant Analysis in Endometriosis

Diagram 1: Non-coding Variant Analysis Workflow for Endometriosis Research. This workflow illustrates the pipeline from whole genome sequencing data to experimental validation, highlighting the critical role of specialized databases in variant annotation and prioritization.

Signaling Pathways in Endometriosis Pathogenesis

Diagram 2: Signaling Pathways in Endometriosis Pathogenesis. This diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways involved in endometriosis, highlighting how genetic variants in estrogen-related genes like ESR1 and GREB1 influence cellular processes that drive disease development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Non-Coding Variant Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Endometriosis Research |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Comprehensive variant detection throughout the genome | Identification of coding and non-coding variants in endometriosis patients [28] |

| NCAD Database | Non-coding variant annotation and interpretation | Functional annotation of regulatory variants in estrogen signaling pathways [26] [23] |

| GREEN-DB & GREEN-VARAN | Regulatory variant prioritization and annotation | HPO-based ranking of candidate regulatory variants in endometriosis cohorts [27] |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction network analysis | Mapping interactions between estrogen receptor genes and regulatory partners [25] |

| VEP (Variant Effect Predictor) | Genomic region mapping and variant consequence prediction | Categorization of non-coding variants by genomic context (UTR, intronic, intergenic) [28] |

| ncVarDB | Benchmarking set of known non-coding variants | Validation of prediction accuracy for endometriosis-associated non-coding variants [28] |

| HPO (Human Phenotype Ontology) | Standardized vocabulary for phenotypic abnormalities | Linking endometriosis clinical presentations to potential non-coding variants [27] |

The interpretation of non-coding variants represents both a challenge and opportunity in endometriosis research. Specialized databases like NCAD and GREEN-DB provide complementary approaches to addressing this challenge. NCAD offers comprehensive variant-centric annotation with extensive population frequency data, while GREEN-DB provides a regulatory element-focused framework with integrated prioritization capabilities [26] [23] [27]. The integration of these databases into structured experimental workflows enables researchers to move from variant identification to functional hypothesis generation, ultimately accelerating the discovery of regulatory mechanisms in endometriosis pathogenesis.

As the field advances, the combination of comprehensive database annotation with experimental validation will be essential to unravel the complex genetic architecture of endometriosis. The convergence of improved annotation databases, advanced computational prediction tools, and high-throughput functional validation technologies promises to enhance our understanding of how non-coding variants contribute to endometriosis risk and progression, potentially identifying new therapeutic targets for this debilitating condition.

Endometriosis, a chronic inflammatory disorder driven by estrogen signaling, affects approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women globally yet often suffers from diagnostic delays spanning up to 11 years between symptom onset and formal diagnosis [30]. While genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous genetic variants associated with advanced-stage disease, the genetic underpinnings of early-stage endometriosis remain poorly understood, creating significant barriers to timely intervention [30]. Emerging research now reveals a sophisticated interplay between ancient genetic regulatory variants and modern environmental exposures in shaping disease susceptibility. This paradigm shift proposes that endometriosis risk emerges not merely from genetic or environmental factors in isolation, but from their complex interaction—specifically, between regulatory DNA sequences inherited from ancient hominin ancestors and contemporary endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) pervasive in modern environments [30] [31].

The validation of non-coding variants presents particular challenges, as over 90% of disease-associated variants identified in GWAS reside outside protein-coding regions [32] [33]. These regulatory elements—including promoters, enhancers, and non-coding RNAs—orchestrate the temporal and tissue-specific expression of genes, meaning variants can potentially dysregulate gene networks critical to disease pathogenesis without altering protein structure [32]. This review systematically compares experimental approaches for validating non-coding variants within the specific context of endometriosis, providing researchers with methodological insights for exploring gene-environment interactions (GEIs) in this complex disorder.

Experimental Landscape for Non-Coding Variant Validation

Current Status of Validation Approaches

The field of non-coding variant validation has developed multifaceted experimental strategies to bridge the gap between statistical associations and biological mechanisms. A comprehensive systematic review examining 309 validated non-coding variants across 130 human diseases revealed distinct patterns in experimental validation approaches [33]. The distribution of these validation methods provides crucial benchmarking data for researchers designing endometriosis studies.

Table 1: Experimental Methods for Validating Non-Coding GWAS Variants

| Validation Method | Application Frequency | Primary Utility in Endometriosis Research |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Analysis | 272 studies | Quantifying expression changes in endometriosis lesions versus normal endometrium |

| Transcription Factor Binding Assays | 175 studies | Determining allele-specific effects on TF binding affinity at regulatory variants |

| Reporter Assays (Luciferase, etc.) | 171 studies | Functional characterization of regulatory element activity across alleles |

| In Vivo Animal Models | 104 studies | Modeling systemic impacts of variants in physiological context |

| Genome Editing (CRISPR, etc.) | 96 studies | Precise manipulation of candidate variants to establish causality |

| Chromatin Interaction Analysis | 33 studies | Mapping physical connections between variants and target gene promoters |

The same systematic review found that validated non-coding variants predominantly operate through cis-regulatory elements (70%), with the remainder functioning through promoters (22%) or non-coding RNAs (8%) [33]. This distribution highlights the importance of prioritizing enhancer-associated variants in endometriosis research.

Specialized Methodologies for Gene-Environment Interactions

Investigating GEIs requires specialized approaches that transcend conventional GWAS methodologies. Recent advancements include information-theoretic metrics such as k-way interaction information (KWII) and total correlation information (TCI), which enable visualization and interpretation of complex interactions between multiple genetic and environmental variables [34]. These approaches help overcome the challenges of high-dimensionality in SNP data and combinatorial explosion in interaction testing.

For well-powered analyses, newer statistical frameworks conceptually aligned with Mendelian randomization have been developed [35]. These approaches screen for interactions across the genome by testing differences between marginal genetic effects (from standard GWAS) and main genetic effects (from models incorporating environmental factors). This method improves detection power for variants whose effects are modified by environmental exposures such as EDCs [35].

Case Study: Ancient Variants and Modern Pollutants in Endometriosis

Experimental Design and Workflow

A groundbreaking study investigating the intersection of ancient hominin genetic contributions and modern environmental pollutants in endometriosis provides an exemplary model for integrative experimental design [30] [31]. The research employed a dual-phase systematic literature review to identify genes implicated in both endometriosis pathophysiology and endocrine-disrupting chemical sensitivity, ultimately selecting five genes (IL-6, CNR1, IDO1, TACR3, and KISS1R) based on tissue expression patterns, pathway involvement, and EDC reactivity [30].

The experimental workflow incorporated whole-genome sequencing data from the Genomics England 100,000 Genomes Project, analyzing nineteen females with clinically confirmed endometriosis against matched controls [30]. The methodology specifically focused on regulatory regions—introns, upstream/downstream sequences, and untranslated regions—rather than coding regions, reflecting the understanding that environmental pollutants are more likely to affect gene expression than protein structure [30].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for identifying ancient regulatory variants interacting with modern pollutants. WGS: Whole Genome Sequencing; LD: Linkage Disequilibrium; EDC: Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals.

Key Findings and Variant Characterization

The investigation identified six regulatory variants significantly enriched in the endometriosis cohort compared to matched controls and the general Genomics England population [30]. Particularly noteworthy were co-localized IL-6 variants rs2069840 and rs34880821, located at a Neandertal-derived methylation site, which demonstrated strong linkage disequilibrium and potential for immune dysregulation [30]. Variants in CNR1 and IDO1, some of Denisovan origin, also showed significant associations, with several overlapping EDC-responsive regulatory regions [30].

Table 2: Validated Regulatory Variants in Endometriosis and Their Characteristics

| Gene | Representative Variant | Ancient Origin | Regulatory Mechanism | EDC Interaction Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | rs2069840, rs34880821 | Neandertal | Methylation site altering immune response | High - overlaps EDC-responsive region |

| CNR1 | rs806372 | Denisovan | Transcriptional regulation of endocannabinoid signaling | Moderate - pathway susceptible to disruption |

| CNR1 | rs76129761 | Denisovan | Transcriptional regulation | Moderate - pathway susceptible to disruption |

| IDO1 | Not specified | Denisovan | Immune tolerance modulation | High - inflammatory pathway disruption |

| TACR3 | Not specified | Not specified | Neuroendocrine signaling | Potential via hormonal disruption |

| KISS1R | Not specified | Not specified | Gonadotropin regulation | Potential via hormonal disruption |

Statistical analyses employed χ² goodness-of-fit tests with Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction to account for multiple hypothesis testing while maintaining statistical power [30]. Linkage disequilibrium analysis further confirmed non-random clustering of specific variants within the endometriosis cohort, with pairwise LD values (D' and r²) calculated using data from the 1000 Genomes Project across multiple populations [30].

Advanced Techniques for Mechanistic Validation

Transcription Factor Binding Disruption Assays

Non-coding variants can exert functional effects by altering transcription factor (TF)-DNA recognition, leading to gene dysregulation [32]. Several high-throughput methods have been developed to quantify how non-coding variants impact TF binding affinities:

SNP-SELEX represents a particularly powerful approach that evaluates differential binding of hundreds of human TFs across thousands of SNP variants simultaneously [32]. The method involves synthesizing an oligonucleotide pool containing 40 base pair genomic DNA fragments centered on SNPs with flanking regions for PCR amplification and barcoding. After expressing and purifying TFs, researchers perform multiple rounds of enrichment followed by sequencing, enabling measurement of hundreds of millions of TF-DNA interactions in a single experiment [32].

Binding Energy Topography by Sequencing (BET-seq) represents another advanced methodology that estimates Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔG) for over one million DNA sequences in parallel at high energetic resolution [32]. This approach can detect binding energy changes as small as ~0.5 kcal/mol between flanking regions, providing exceptional sensitivity for quantifying the functional impact of non-coding variants.

Functional Genomic and Epigenomic Approaches

Beyond TF binding, comprehensive variant validation requires multiple orthogonal methods:

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs) enable high-throughput functional screening of thousands of regulatory elements and their variants simultaneously [32]. These assays typically clone oligonucleotide libraries containing candidate regulatory sequences into vectors upstream of a minimal promoter and reporter gene, then transfer them into relevant cell types to quantify allele-specific effects on transcriptional activity.

Chromatin Conformation Capture Techniques (such as Hi-C and ChIA-PET) map physical interactions between non-coding regulatory elements and their target gene promoters, determining whether variants disrupt three-dimensional chromatin architecture [32]. This approach is particularly relevant for endometriosis research, as many disease-associated variants may affect gene regulation through distal enhancer elements.

Diagram 2: Mechanisms through which non-coding variants influence disease pathogenesis. TF: Transcription Factor.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GEI Studies in Endometriosis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | Genomics England 100,000 Genomes Project, GWAS Catalog | Access to large-scale genomic data with clinical phenotypes |

| Epigenomic Annotation | ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics | Chromatin states, TF binding sites, histone modifications |

| Functional Prediction | SNP2TFBS, atSNP, motifbreakR | In silico prediction of variant effects on TF binding |

| Population Genetics | 1000 Genomes Project, gnomAD | Allele frequencies across populations, LD reference |

| Experimental Validation | BET-seq, SNP-SELEX, CASCADE | High-throughput measurement of variant effects |

| EDC Exposure Assessment | Environmental contaminant screening assays | Quantifying pollutant levels in biological samples |

| Nickel potassium fluoride | Nickel potassium fluoride, CAS:13845-06-2, MF:F3KNi, MW:154.787 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Hydroxymethylaminopyrine | 3-Hydroxymethylaminopyrine, CAS:13097-17-1, MF:C13H17N3O2, MW:247.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

These resources collectively enable a comprehensive approach to validating non-coding variants in endometriosis, from initial computational predictions through high-throughput experimental confirmation to functional characterization in disease-relevant models.

The investigation of gene-environment interactions in endometriosis represents a paradigm shift from focusing exclusively on genetic or environmental risk factors toward understanding their complex interplay. The discovery that ancient hominin-derived regulatory variants interact with modern environmental pollutants provides a novel perspective on disease susceptibility, suggesting that genetic legacies from our evolutionary past may confer vulnerability to contemporary environmental exposures [30] [31].

For researchers pursuing this emerging field, success requires integrating diverse methodologies—from population genetic analyses that identify signatures of ancient introgression to molecular assays that quantify how variants alter regulatory element function in the presence of environmental contaminants. The experimental frameworks and validation approaches detailed in this review provide a roadmap for systematically investigating these complex relationships, with potential applications not only in endometriosis but across numerous complex traits where gene-environment interactions remain incompletely characterized.

As the field advances, key challenges include developing more sophisticated in vitro models that recapitulate the tissue microenvironment of endometriosis lesions, incorporating broader exposomic data beyond EDCs, and advancing multi-omic integration approaches that can simultaneously capture genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, and environmental contributions to disease pathogenesis. The ongoing development of increasingly powerful functional genomics tools promises to accelerate this progress, potentially unlocking new opportunities for early detection, prevention, and targeted intervention in this complex disorder.

A Toolkit for Functional Validation: From In Silico to In Vivo Models

Endometrial stromal cells (ESCs) are not merely structural components of the endometrium; they are functionally integral to the pathophysiology of endometriosis, particularly in the context of non-coding RNA research. These cells undergo a complex process known as decidualization, which is critically impaired in endometriosis, contributing to the progesterone resistance that characterizes the disease [36]. The establishment of physiologically relevant in vitro models of ESCs has become paramount for investigating the functional consequences of non-coding genetic variants identified through genome-wide association studies. Recent advances in three-dimensional (3D) culture systems have enabled researchers to more accurately model the stromal-epithelial interactions and extracellular matrix dynamics that occur in vivo, providing unprecedented opportunities to dissect the molecular mechanisms by which non-coding variants influence gene regulatory networks in endometriosis [37] [38]. This guide objectively compares the current landscape of endometrial stromal cell culture models, their experimental applications, and their specific utility for validating the functional impact of non-coding variants in endometriosis research.

Comparison of Endometrial Stromal Cell Culture Models

The choice of in vitro model significantly influences the physiological relevance and translational potential of research findings. The following table compares the primary stromal cell culture systems used in endometriosis research.

Table 1: Comparison of Endometrial Stromal Cell Culture Models for Functional Assays

| Model Type | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations | Primary Applications in Endometriosis Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Monolayer Cultures | - Plastic-adherent primary cells or immortalized lines- Grown in flat, two-dimensional format [38] | - Technical simplicity and low cost- High reproducibility and scalability- Suitable for high-throughput screening- Easy genetic manipulation (e.g., transfection) [39] | - Loss of native 3D architecture and cell polarity- Altered cell-ECM interactions- May not fully recapitulate in vivo signaling pathways [38] | - Initial functional validation of non-coding variants [40]- siRNA/CRISPR screens- Migration and invasion assays [39] |

| 3D Organoid Co-Cultures | - 3D microstructures incorporating epithelial and stromal components [37] [41]- Embedded in ECM scaffolds like Matrigel [41] | - Preserves native tissue architecture and cell heterogeneity- Enables study of stromal-epithelial crosstalk- Recapitulates hormone response and secretory function [36] [37] | - Technically challenging and higher cost- Longer culture establishment time- Variable success rates between patient samples [41] | - Modeling stromal-epithelial interactions in endometriotic lesions [37]- Studying the endometriotic niche and microenvironment [38] |

| Endometrial Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (eMSC) | - Perivascular origin (CD140b+/CD146+/SUSD2+) [42]- Self-renewing, clonogenic population | - Can be isolated from endometrial tissue or menstrual effluent (MenSC) [42]- High proliferative capacity- Potential role in endometriosis pathogenesis | - Require specific marker isolation- Phenotypic stability in long-term culture requires optimization | - Investigating origins and recurrence of endometriosis [42]- Disease modeling from patient-specific cells |

| 2,3,5,6-Tetrachloropyridine-4-thiol | 2,3,5,6-Tetrachloropyridine-4-thiol, CAS:10351-06-1, MF:C5HCl4NS, MW:248.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Spiro[4.4]nonan-1-one | Spiro[4.4]nonan-1-one|CAS 14727-58-3|Supplier | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocols for Key Functional Assays

Protocol: Cell Viability and Proliferation Assay (Cell Counting Kit-8)

The CCK-8 assay provides a quantitative measure of stromal cell viability and proliferation, which is crucial for assessing the impact of genetic manipulations on cell growth.

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed human endometrial stromal cells (hEnSCs) in a 96-well plate at a density of 1-5 x 10³ cells per well in 100 µL of complete medium. Include blank wells (medium only) for background subtraction [39].

- Experimental Treatment: After cell attachment, introduce the experimental conditions. This may include:

- CCK-8 Incubation: At designated time points (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours), add 10 µL of CCK-8 solution directly to each well.

- Absorbance Measurement: Incubate the plate at 37°C for 1-4 hours. Measure the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The amount of formazan dye generated is proportional to the number of viable cells.

- Data Analysis: Subtract the background absorbance (blank wells). Normalize data to the control group and present as mean ± standard deviation from at least three independent experiments.

Protocol: Colony Formation Assay

This assay evaluates the clonogenic potential of stromal cells, reflecting their capacity for sustained growth and proliferation—a key characteristic in disease pathogenesis.

Detailed Methodology:

- Low-Density Seeding: Seed transfected or treated hEnSCs in 6-well plates at a very low density (200-500 cells per well) to allow isolated colony formation [39].

- Culture Period: Culture the cells for 10-14 days, refreshing the medium every 3-4 days.

- Fixation and Staining: Once macroscopic colonies are visible, carefully aspirate the medium. Wash with PBS, then fix the colonies with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15-20 minutes. Stain with 0.1% crystal violet solution for 30 minutes.

- Colony Counting: Gently rinse the plate with water to remove excess stain. Air-dry the plate and count the number of colonies (typically defined as clusters >50 cells) manually or using automated colony counting software.

Protocol: Scratch Wound Healing Assay

The scratch assay is a simple and effective method to assess the migratory capacity of endometrial stromal cells, a property relevant to the establishment of endometriotic lesions.

Detailed Methodology:

- Confluent Monolayer Preparation: Seed hEnSCs in a 12-well or 24-well plate to achieve 90-100% confluency within 24-48 hours.

- Scratch Creation: Use a sterile 200 µL pipette tip to create a uniform, straight "scratch" through the cell monolayer. Gently wash the well with PBS to remove dislodged cells.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Add fresh, serum-free or low-serum medium. Immediately capture images of the scratch at time zero at predefined points along the scratch using an inverted microscope. Capture images at the same locations at regular intervals (e.g., 12, 24 hours).

- Quantification: Measure the change in the scratch width (wound area) over time using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ). Calculate the percentage of wound closure relative to the initial scratch area.

Signaling Pathways in Endometrial Stromal Cells

Research has identified key signaling pathways that are dysregulated in endometriosis and can be studied using the described in vitro models. The diagram below illustrates the MAPK/AP-1 and HOXA11-AS associated pathways.