Hormonal Control of Endometrial Gene Expression: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on how ovarian steroid hormones estradiol and progesterone orchestrate dynamic gene expression programs in the human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle.

Hormonal Control of Endometrial Gene Expression: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on how ovarian steroid hormones estradiol and progesterone orchestrate dynamic gene expression programs in the human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. We explore foundational transcriptomic and epigenetic mechanisms, advanced organoid and single-cell methodologies for studying endometrial biology, challenges in biomarker discovery and personalized medicine applications, and validation approaches through genetic mapping and clinical testing. By integrating insights from recent single-cell RNA sequencing, epigenetic analyses, and endometrial receptivity studies, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a multifaceted understanding of endometrial gene regulation and its implications for treating infertility and endometrial disorders.

Cyclical Transcriptomes and Epigenetic Landscapes: How Hormones Shape Endometrial Gene Expression

Estradiol and Progesterone Signaling Networks in Endometrial Tissue Remodeling

The endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus, undergoes dramatic cyclical remodeling throughout the menstrual cycle in preparation for embryo implantation. This dynamic process is primarily orchestrated by the ovarian steroid hormones estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4), which coordinate complex transcriptional and cellular programs via their respective nuclear receptors [1] [2]. Estrogen dominates the proliferative phase, stimulating endometrial growth and regeneration, while progesterone during the secretory phase promotes glandular secretion and stromal differentiation—a process known as decidualization [2] [3]. The synchronized actions of these hormones ensure the brief period of endometrial receptivity known as the window of implantation (WOI), typically occurring on cycle days 20-24 in humans [4] [2]. Disruption of these precisely coordinated signaling networks underpins various endometrial pathologies, including endometriosis, implantation failure, and endometrial cancer [1] [3]. This review synthesizes current understanding of E2 and P4 signaling mechanisms governing endometrial gene expression and tissue remodeling, providing a foundational context for research on hormonal control of endometrial function.

Molecular Mechanisms of Hormone Receptor Signaling

Estrogen Receptor Signaling Pathways

Estrogen exerts its biological effects primarily through two nuclear receptors, estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ), which are expressed in multiple endometrial cell types including epithelial, stromal, and vascular cells [1]. Both receptors share a common domain structure comprising an N-terminal transcriptional activation function (AF-1) domain, a central DNA-binding domain (DBD), a hinge region, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) that contains the ligand-dependent activation function (AF-2) region [1]. Despite structural similarities, ERα and ERβ demonstrate distinct transcriptional activities and functional roles in the endometrium, with ERα predominantly mediating proliferative responses while ERβ may counterbalance ERα activity [1].

Estrogen signaling occurs through multiple mechanistic pathways. In the classical genomic pathway, ligand-bound ER dimers bind directly to estrogen response elements (EREs) in target gene promoters, recruiting co-regulator complexes to modulate transcription [1]. In non-classical pathways, ERs can tether to other transcription factors such as AP-1 and SP-1 without directly binding DNA. Additionally, membrane-associated receptors including G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) initiate rapid non-genomic signaling by activating secondary messengers and kinase cascades [1]. The expression patterns of these receptors are dynamically regulated throughout the menstrual cycle, with ERα notably downregulated during the implantation window in a progesterone-dependent manner, a change critical for establishing endometrial receptivity [4].

Progesterone Receptor Signaling and Antagonistic Functions

Progesterone signals through two main nuclear receptor isoforms, PRA and PRB, which are transcribed from the same gene but under different promoters [2]. PRB contains an additional 164 N-terminal amino acids and generally functions as a stronger transcriptional activator, while PRA often acts as a dominant-negative repressor of PRB activity [2]. In the human endometrium, both isoforms are expressed during the proliferative phase, but PRA becomes dominant in the early secretory phase, with PRB levels rising again during the mid-secretory phase [2].

Progesterone receptor signaling similarly involves genomic mechanisms where ligand-activated PR complexes bind progesterone response elements (PREs) to regulate target gene transcription [2]. The functional impact of progesterone signaling is highly context-dependent, with P4 generally opposing estrogen-driven proliferation by downregulating ER expression and promoting endometrial differentiation [2] [3]. This antagonistic relationship is crucial for the transition from the proliferative to secretory phase, with aberrant PR signaling or expression linked to impaired decidualization and endometrial receptivity defects [3].

Table 1: Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors in the Endometrium

| Receptor Type | Isoforms | Main Functions in Endometrium | Expression Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen Receptor (ER) | ERα | Mediates epithelial proliferation, regulates implantation-related genes | High in proliferative phase, downregulated in secretory phase |

| ERβ | May counterbalance ERα activity, anti-proliferative effects | Expressed throughout cycle, function less defined | |

| Membrane Estrogen Receptor | GPER | Rapid non-genomic signaling, activates MAPK/PI3K pathways | Expressed in epithelium and stroma |

| Progesterone Receptor (PR) | PRA | Dominant-negative regulator of PRB, important for secretory changes | Dominant in early secretory phase |

| PRB | Strong transcriptional activator, promotes decidualization | Higher in mid-secretory phase |

Quantitative Analysis of Receptor Dynamics

Temporal Expression Patterns During the Menstrual Cycle

Advanced molecular techniques have enabled precise quantification of steroid hormone receptor dynamics throughout endometrial development. A 2020 study investigating endometrial samples from oocyte donors revealed statistically significant variations in both ERα and PR-B expression between day 0 (oocyte retrieval) and day 5 (implantation window) of the cycle [4]. Wilcoxon signed-rank test analysis demonstrated dramatic reductions in both receptors during this critical period, with P-values of P=0.0001 for ER nodal and stromal percentages, and P=0.0001 and P=0.035 for PR nodal and stromal percentages, respectively [4]. These quantitative findings confirm the progesterone-mediated downregulation of steroid receptors essential for acquisition of endometrial receptivity.

Further analysis revealed age-associated differences in ERα expression patterns, with patients under 30 years exhibiting 100% nodal staining on day 0 compared to 90% in women over 30 (P=0.014) [4]. This finding suggests potential molecular mechanisms underlying age-related declines in endometrial receptivity and highlights the importance of considering patient age in both research and clinical applications.

Hormonal Regulation of Receptor Expression

Experimental models have provided additional insights into hormonal cross-talk regulating receptor expression. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies using endometrial cell lines (HEC1A, RL95-2) demonstrated that each steroid hormone receptor targets distinct gene groups, with estrogen treatment resulting in ER binding to 137 target genes in non-receptive HEC1A cells compared to only 35 in receptive RL95-2 cells [2]. Conversely, progesterone treatment generated PR binding to 83 targets in RL95-2 cells versus merely 7 in HEC1A cells, highlighting the cell-type and differentiation state specificity of hormonal signaling [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Changes in Steroid Hormone Receptors During the Implantation Window

| Receptor | Location | Day 0 Expression | Day 5 Expression | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | Nodal | 100% (<30y), 90% (>30y) | Significantly reduced | P=0.0001 |

| Stromal | High | Significantly reduced | P=0.0001 | |

| PR-B | Nodal | High | Significantly reduced | P=0.0001 |

| Stromal | High | Significantly reduced | P=0.035 |

Genomic and Non-Genomic Signaling Networks

Transcriptional Regulation of Endometrial Genes

Estradiol and progesterone coordinate endometrial remodeling through extensive transcriptional networks targeting genes involved in cell adhesion, extracellular matrix organization, immune modulation, and cellular differentiation. Research investigating 382 genes differentially expressed during the implantation window identified direct regulation by steroid hormone receptors through promoter binding [2]. Notably, progesterone signaling through PR isoforms activates genes critical for decidualization, including those encoding extracellular matrix components, growth factors, and immunomodulators [2] [3].

Recent single-cell RNA sequencing analyses have further refined understanding of cell-type-specific transcriptional responses to hormonal signaling. In stromal fibroblasts, progesterone signaling activates genes associated with cytoskeletal remodeling and differentiation, while in epithelial cells it represses pro-inflammatory pathways [3]. Serum response factor (SRF) has been identified as a key transcription factor interacting with hormonal signaling, particularly in regulating cytoskeletal genes during decidualization and suppressing epithelial inflammation [3]. Dysregulation of these transcriptional networks, as observed in endometriosis patients with decreased endometrial SRF expression, contributes to impaired decidualization and infertility [3].

Integrated Signaling in Endometrial Remodeling

The genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways of estradiol and progesterone converge to coordinate the complex process of endometrial remodeling. Estrogen signaling through both nuclear ER and membrane GPER activates growth factor pathways including EGFR, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT, which promote cellular proliferation and survival during the regenerative and proliferative phases [1]. Progesterone signaling subsequently dampens estrogen-driven proliferation while activating differentiation programs through both genomic mechanisms and rapid non-genomic signaling involving secondary messengers.

A critical aspect of this integrated signaling is the regulation of endometrial receptivity markers, including integrins, selectins, and cadherins [4]. Progesterone drives increased expression of integrin αvβ3 in epithelial cells, facilitating embryo attachment, while estrogen regulates E-cadherin expression important for epithelial integrity [4]. The dynamic interplay between these signaling networks ensures proper timing of the implantation window, with dysregulation leading to displaced WOI and implantation failure [5].

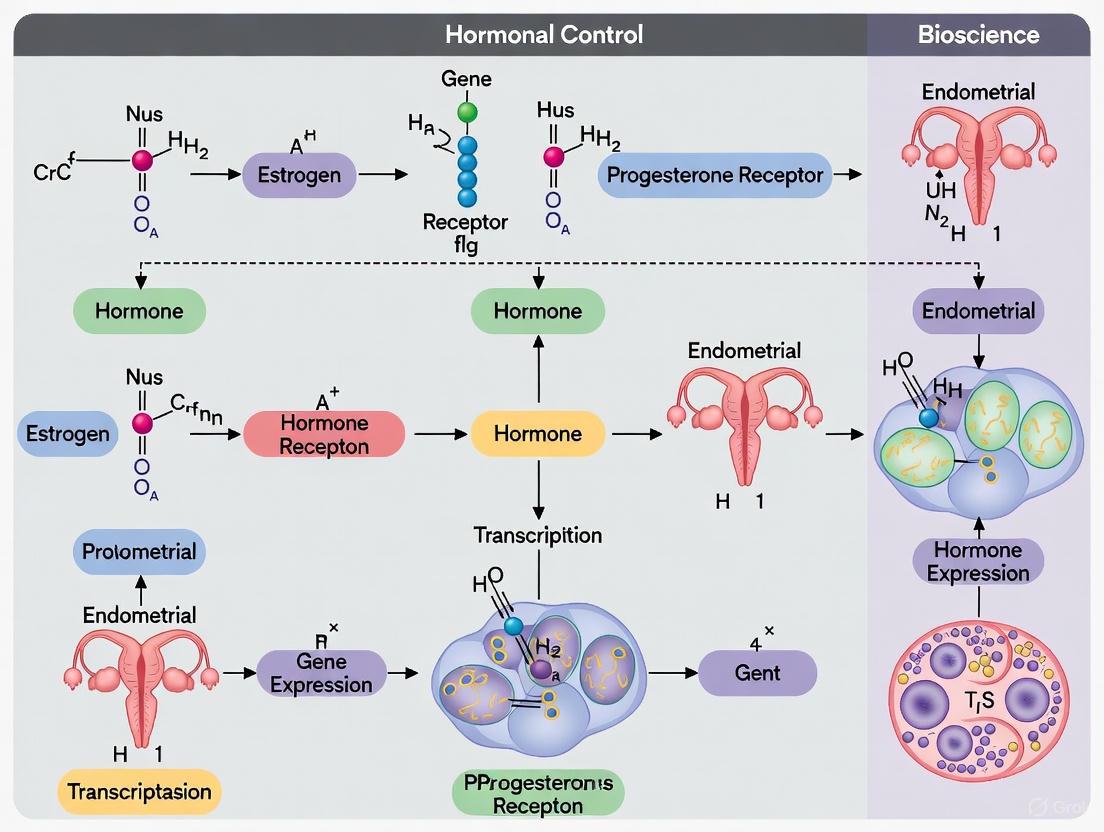

Diagram 1: Estradiol and Progesterone Signaling Networks in Endometrial Cells. This diagram illustrates the complex interplay between genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways activated by E2 and P4 in endometrial cells, highlighting the cross-regulation between receptor systems.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Models for Studying Endometrial Signaling

Various experimental systems have been developed to investigate E2 and P4 signaling in endometrial tissue. Immortalized human endometrial cell lines including HEC1A and RL95-2 provide reproducible models for studying hormone responsiveness, with RL95-2 cells particularly valuable as a model of receptive endometrium due to their enhanced adhesiveness for embryonic cells [2]. Primary endometrial stromal cells (HESCs) maintain critical in vivo characteristics including decidualization capacity in response to hormonal stimulation, making them essential for functional studies [3].

Recent advances in organoid technology have revolutionized endometrial research by enabling long-term expansion of primary epithelial cells that retain tissue-specific functions and hormone responsiveness [6]. Endometrial organoids recapitulate glandular architecture and express appropriate steroid hormone receptors, allowing investigation of epithelial-specific responses in a physiologically relevant context [6]. Microfluidic systems further enhance these models by incorporating mechanical stimuli including uterine peristaltic movement, enabling more accurate simulation of the endometrial microenvironment [6].

Key Methodological Approaches

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by quantitative PCR has been instrumental for identifying direct transcriptional targets of steroid hormone receptors. The standard protocol involves formaldehyde cross-linking of DNA-protein complexes, immunoprecipitation with receptor-specific antibodies (e.g., ERα, ERβ, PR), and quantification of bound genomic sequences [2]. This approach has identified hundreds of ER and PR binding sites in endometrial cells, revealing the extensive genomic networks regulated by these receptors.

For functional validation, RNA interference techniques (siRNA/shRNA) effectively knock down receptor expression in primary HESCs, enabling investigation of downstream consequences on decidualization, cytoskeletal organization, and cell viability [3]. Combined with transcriptomic analyses (RNA-seq), this approach has demonstrated that SRF deficiency in stromal cells disrupts actin cytoskeleton organization and blunts decidualization markers including IGFBP1 and PRL [3].

Immunohistochemistry remains essential for spatial localization of receptors and signaling components in endometrial tissue sections. Quantitative image analysis using software such as ImageJ enables precise measurement of staining intensity and distribution across epithelial and stromal compartments [4] [7]. This technique has demonstrated dynamic changes in ERα and PR expression patterns throughout the menstrual cycle and in pathological conditions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Endometrial Hormone Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | RL95-2 cell line | Receptive endometrium model | Studies of embryo-endometrial dialogue |

| Primary HESCs | Decidualization studies | Stromal fibroblast differentiation | |

| Endometrial organoids | Epithelial function studies | 3D modeling of glandular physiology | |

| Antibodies | Anti-ERα (Clone 4f11) | IHC, ChIP | Detection and localization of ERα |

| Anti-PR (clone 16+SAN27) | IHC, Western blot | Progesterone receptor identification | |

| Anti-SRF | IHC, Functional studies | Transcription factor analysis | |

| Chemical Reagents | 4-hydroxytamoxifen | CreER lineage tracing | Genetic cell fate mapping |

| Estradiol + MPA + cAMP | Decidualization induction | In vitro stromal differentiation | |

| G-1 and G-15 | GPER studies | Specific GPER agonism/antagonism |

Technical Protocols for Key Experiments

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for Steroid Receptor Genomic Binding

The following protocol adapted from Saare et al. (2009) details the procedure for identifying genomic targets of ER and PR in endometrial cell lines [2]:

Cell Culture and Hormone Treatment:

- Culture HEC1A or RL95-2 cells in appropriate media (McCoy 5A for HEC1A, DMEM/F12 for RL95-2) with 10% fetal bovine serum.

- 48 hours before experiments, switch to phenol-red free media with dextran-coated charcoal-treated FBS to eliminate hormone effects.

- Treat cells with 10 nM estradiol (E2) or progesterone (P4) for 45 minutes for ChIP experiments or 3-12 hours for mRNA analysis.

Cross-linking and Cell Lysis:

- Add 1% formaldehyde directly to culture media for 15 minutes at room temperature to cross-link DNA-protein complexes.

- Quench cross-linking with 125 mM glycine for 5 minutes.

- Wash cells twice with ice-cold PBS, harvest by scraping, and pellet by centrifugation.

Chromatin Preparation and Immunoprecipitation:

- Resuspend cell pellets in SDS lysis buffer and incubate on ice for 10 minutes.

- Sonicate chromatin to fragment DNA to 200-1000 bp fragments using a Vibra-Cell ultrasonic processor.

- Dilute lysate 10-fold in ChIP dilution buffer and pre-clear with protein A/G beads for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Incubate supernatant with 2-5 μg of specific antibodies (ERα: D-12, sc-8005; ERβ: H-150, sc-8974; PR: AB-52, sc-810) overnight at 4°C with rotation.

- Precipitate immune complexes with GammaBind Plus Sepharose beads for 2 hours.

- Wash beads sequentially with low salt, high salt, LiCl immune complex wash buffers, and TE buffer.

DNA Recovery and Analysis:

- Elute chromatin from beads with elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3).

- Reverse cross-links by adding 5 M NaCl and incubating at 65°C overnight.

- Treat samples with Proteinase K, purify DNA using silica membrane columns.

- Analyze precipitated DNA by quantitative PCR with primers designed for regions of interest.

Endometrial Stromal Cell Decidualization Protocol

This protocol for in vitro decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells (HESCs) is adapted from recent publications [3]:

Primary HESC Isolation and Culture:

- Obtain endometrial biopsies or collect menstrual effluent by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 minutes.

- Digest minced tissue with 0.2% collagenase type IA in DMEM/F12 for 60-90 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Filter cell suspension through 40 μm and 20 μm sieves sequentially to separate glandular epithelial cells from stromal cells.

- Culture stromal cells in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% amphotericin B at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Decidualization Induction:

- At 80-90% confluence, switch to decidualization medium consisting of phenol-red free DMEM/F12 with 2% charcoal-stripped FBS, 1 μM medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), 0.5 mM 8-bromo-cAMP, and 10 nM 17β-estradiol.

- Refresh decidualization medium every 2-3 days for 6-12 days depending on experimental requirements.

Decidualization Validation:

- Monitor morphological changes from fibroblastic to rounded, epithelioid appearance.

- Measure established decidualization markers by RT-qPCR or ELISA: prolactin (PRL) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGFBP1).

- Assess cytoskeletal reorganization by phalloidin staining for F-actin.

Diagram 2: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps in ChIP methodology for identifying genomic binding sites of steroid hormone receptors in endometrial cells.

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Clinical Implications of Signaling Disruption

Dysregulation of E2 and P4 signaling networks contributes significantly to various endometrial disorders. In endometriosis, aberrant estrogen signaling with concomitant progesterone resistance creates a inflammatory microenvironment characterized by defective decidualization and impaired endometrial receptivity [8] [3]. Single-cell RNA sequencing of endometriosis patient tissues has revealed decreased expression of critical transcription factors including SRF in both epithelial and stromal compartments, associated with cytoskeletal disorganization and blunted decidualization response [3].

Recurrent implantation failure (RIF) represents another condition with disrupted hormonal signaling, often featuring displaced window of implantation (WOI) [5]. Molecular diagnostic approaches including endometrial receptivity analysis (ERA) have identified significant correlations between patient age, number of previous failed embryo transfer cycles, and displaced WOI incidence [5]. Clinical studies demonstrate that personalized embryo transfer (pET) guided by ERA improves pregnancy rates in RIF patients from 49.3% to 62.7% and live birth rates from 40.4% to 52.5% [5].

In polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), metabolic disturbances including hyperinsulinemia synergize with hormonal imbalances to disrupt endometrial function [9]. Insulin resistance alters PI3K/AKT/MAPK signaling pathways, while chronic inflammation and hyperandrogenism interfere with normal estrogen and progesterone receptor signaling, resulting in impaired decidualization and increased pregnancy complications [9].

Therapeutic Targeting of Hormone Signaling Pathways

Understanding endometrial E2 and P4 signaling networks has enabled development of targeted therapeutic approaches. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) including tamoxifen and raloxifene, and selective estrogen receptor downregulators (SERDs) such as fulvestrant, provide tools for manipulating estrogen signaling in endometrial pathologies [1]. For progesterone signaling, selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) offer potential for managing conditions including endometriosis and endometrial hyperplasia.

Emerging computational approaches including quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) models integrate knowledge of hormonal signaling networks to predict treatment responses and optimize therapeutic strategies for endometrial disorders [8]. These models synthesize data on drug pharmacokinetics, receptor binding dynamics, and downstream signaling pathways to simulate patient-specific responses to hormonal manipulations [8].

Novel therapeutic strategies targeting the inflammatory components of endometrial disorders are also under development. Based on findings that SRF deficiency promotes endometrial inflammation and fibrosis, interventions aimed at restoring SRF expression or activity represent promising avenues for treating endometriosis-related infertility [3].

The signaling networks activated by estradiol and progesterone in endometrial tissue represent a sophisticated regulatory system that coordinates cyclical tissue remodeling, endometrial receptivity, and embryo implantation. The integration of genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways, combined with complex cross-talk between receptor systems, enables precise temporal and spatial control of endometrial function. Disruption of these networks underlies significant endometrial pathologies including endometriosis, implantation failure, and endometrial cancer.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the single-cell resolution dynamics of hormonal signaling throughout the menstrual cycle, particularly during critical transitions such as the implantation window. Advanced organoid and microfluidic systems that better recapitulate the endometrial microenvironment will enable more physiologically relevant investigation of hormonal regulation. Additionally, computational modeling approaches integrating multi-omics data will provide unprecedented insights into the systems-level control of endometrial function by steroid hormones.

The continued refinement of our understanding of estradiol and progesterone signaling networks in the endometrium will undoubtedly yield novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for endometrial disorders, ultimately improving reproductive outcomes and women's health.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Phase-Specific Transcriptional Programs

The human endometrium undergoes profound, cyclic remodeling throughout a woman's reproductive life, characterized by sequential phases of proliferation, secretion, and shedding. This dynamic tissue transformation is exquisitely controlled by ovarian hormones—estrogen and progesterone—which regulate complex transcriptional programs to prepare the endometrium for embryo implantation. Understanding the hormonal control of endometrial gene expression at cellular resolution provides critical insights into reproductive success and the pathogenesis of gynecological diseases.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a transformative technology that enables researchers to decipher cellular heterogeneity and characterize phase-specific transcriptional programs within complex tissues. Unlike bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across cell populations, scRNA-seq reveals the unique transcriptomic signatures of individual cells, allowing for the identification of rare cell types, transitional states, and nuanced responses to hormonal cues [10]. This technical guide explores how scRNA-seq is illuminating the molecular mechanisms underlying endometrial physiology and pathology, with particular emphasis on hormonal regulation across the menstrual cycle.

scRNA-seq Technology: Principles and Workflows

Fundamental Technological Principles

Single-cell RNA sequencing technology has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling researchers to profile gene expression at unprecedented resolution. The core principle involves isolating individual cells, converting their RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), amplifying these transcripts, and preparing sequencing libraries that preserve cell-of-origin information through genetic barcoding [10]. Since its conceptual breakthrough in 2009, scRNA-seq has evolved rapidly, with throughput increasing from a few cells to hundreds of thousands of cells per experiment while costs have decreased dramatically [10].

The experimental workflow consists of several critical steps: (1) single-cell isolation and capture, (2) cell lysis, (3) reverse transcription (converting RNA to cDNA), (4) cDNA amplification, and (5) library preparation [10]. Among these, single-cell capture, reverse transcription, and cDNA amplification present the most significant technical challenges. Current high-throughput methods utilize microfluidic-microwell, droplet-based, or in situ barcoding approaches to process thousands of cells simultaneously [10].

A key innovation in scRNA-seq is the incorporation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), which tag each mRNA molecule during reverse transcription. UMIs enable accurate quantification by correcting for PCR amplification biases, thereby enhancing the quantitative nature of scRNA-seq data [10]. The choice between full-length transcript protocols (e.g., Smart-seq2) and 3'-end counting methods (e.g., 10x Genomics) depends on the specific research questions, with the former providing more complete transcript information and the latter enabling higher throughput [11] [10].

Experimental Design Considerations

Designing a robust scRNA-seq experiment requires careful consideration of multiple factors to ensure biologically meaningful results:

Sample Type Selection: Researchers must decide whether to sequence whole cells or nuclei. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) is particularly valuable for tissues difficult to dissociate (e.g., brain, fibrous tissues) or when working with frozen clinical samples, as it minimizes artificial stress responses induced by tissue dissociation [10] [12]. For endometrial studies, snRNA-seq enables the use of valuable biobanked specimens collected throughout the menstrual cycle.

Replication Strategy: Both technical and biological replicates are essential. Technical replicates (processing the same sample multiple times) measure protocol variability, while biological replicates (different subjects under identical conditions) capture inherent biological variability and ensure reproducibility [12]. For menstrual cycle studies, biological replicates across different phases and multiple donors are crucial.

Fresh vs. Fixed Samples: While fresh samples ideally capture native transcriptional states, fixation permits sample storage and batched processing, which is particularly valuable for clinical samples obtained at unpredictable times or large-scale time-course experiments [12]. Fixed samples minimize batch effects in studies examining multiple menstrual cycle phases.

Cell Throughput and Sequencing Depth: There is an inherent trade-off between the number of cells sequenced, sequencing depth per cell, and the number of samples included. For cell-type-specific expression quantitative trait locus (ct-eQTL) mapping, sequencing more samples with lower coverage per cell increases statistical power more than deep sequencing of fewer samples [13]. This design principle is particularly relevant for population-scale studies of endometrial gene regulation.

Table 1: Key Decisions in scRNA-seq Experimental Design

| Design Factor | Options | Considerations | Endometrial Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Whole cells vs. Nuclei | Nuclei preferable for difficult-to-dissociate tissues or frozen samples; whole cells capture cytoplasmic transcripts | Endometrial biopsies processed immediately (cells) vs. archived frozen samples (nuclei) |

| Replication | Technical vs. Biological | Technical replicates assess protocol noise; biological replicates capture donor variability | Multiple donors per menstrual phase account for interpersonal variation |

| Sample Processing | Fresh vs. Fixed | Fresh: optimal transcriptome preservation; Fixed: enables batching, clinical logistics | Fixed samples allow pooling across multiple cycle phases for direct comparison |

| Sequencing Strategy | High depth (fewer cells) vs. Low depth (more cells) | Low coverage with more cells increases power for population studies | Optimal for detecting rare cell populations in endometrial tissue across cycle phases |

Analysis of Phase-Specific Transcriptional Programs in the Endometrium

scRNA-seq Unravels Menstrual Cycle Dynamics

The application of scRNA-seq to endometrial tissue has revealed remarkable cellular heterogeneity and precise transcriptional changes across the menstrual cycle. A comprehensive analysis of 59,770 cells from normal endometrium identified 13 distinct cell clusters, with specific populations exhibiting phase-dependent expansion and regression [14]. Perivascular CD9+SUSD2+ cells emerged as putative progenitor cells with functions enriched in ossification, stem cell development, and wound healing—processes critical to cyclic endometrial regeneration [14].

Histological analysis demonstrated a significant perivascular expression pattern of CD9+SUSD2+ cells that varied across menstrual cycle phases, with higher abundance during the proliferative phase compared to the secretory phase [14]. This pattern aligns with the estrogen-driven regenerative program that dominates the proliferative phase, preparing the endometrium for potential implantation.

RNA velocity analysis, which predicts future cell states based on spliced and unspliced mRNA ratios, has established trajectory relationships between cell populations across the menstrual cycle [14]. This computational approach can delineate the developmental pathways through which progenitor cells differentiate into specialized endometrial cell types in response to hormonal cues.

Hormonal Regulation of Endometrial Cell Populations

scRNA-seq has enabled unprecedented resolution in mapping hormonal responses across different endometrial cell types. In the proliferative phase, estrogen signaling drives the expansion of epithelial and stromal compartments, with distinct transcriptional programs evident in each cell lineage [14]. During the secretory phase, progesterone signaling activates gene networks that support endometrial receptivity, including those involved in decidualization, nutrient transport, and immunomodulation.

A notable discovery from scRNA-seq is the identification of specialized epithelial subpopulations with unique hormone responsiveness. In adenomyosis patients, researchers identified a distinct "ECM-high epithelial cell" subpopulation that co-expressed both epithelial (EPCAM) and fibroblast (DCN) markers [15]. This hybrid cell population expanded in pathological states and exhibited altered hormonal response patterns, particularly to prolactin signaling [15].

Fibroblast subclusters also demonstrate phase-specific functional specialization. In the normal endometrium, fibroblasts differentiate into decidual stromal cells (ds1 and ds2) and pre-decidual stromal cells (Pre-ds) during the secretory phase, each with distinct transcriptional profiles [15]. The Pre-ds subcluster is characterized by proliferation-related genes (MKI67, TOP2A, CENPF, CDK1, CCNB1), while ds1 and ds2 cells exhibit differentiated phenotypes with unique signaling activities [15].

Table 2: Phase-Specific Endometrial Cell Populations and Their Transcriptional Programs

| Cell Type | Proliferative Phase Signature | Secretory Phase Signature | Putative Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD9+SUSD2+ Perivascular Cells | High abundance; enriched in stem cell development, wound healing | Reduced abundance | Progenitor function, tissue regeneration |

| Epithelial Subpopulations | Proliferation-associated genes; estrogen-responsive genes | Secretory programs; implantation factors | Lumen formation, glandular secretion, embryo attachment |

| Decidual Stromal Cells (ds1) | Low abundance | High DKK1, WNT4; decreased TGFβ and IGF signaling | Differentiated state, stromal remodeling |

| Decidual Stromal Cells (ds2) | Low abundance | High EGR1, IER2, TXNIP; stress response genes | Environmental sensing, stress adaptation |

| Endothelial Cells | Moderate angiogenic activity | Enhanced VEGF signaling, particularly CapECs | Vascular support, nutrient delivery |

Signaling Pathways in Endometrial Homeostasis and Pathology

Cell-Cell Communication Networks

CellChat analysis of scRNA-seq data has revealed intricate cell-cell communication networks that shift across the menstrual cycle. In the normal proliferative phase, signaling pathways that promote cellular proliferation and vascular development dominate, while secretory phase communications emphasize immune modulation and tissue stabilization [14].

In thin endometrium (TE), a condition associated with infertility, these communication networks become disrupted. scRNA-seq of proliferative phase endometrium from TE patients and controls revealed "TE-associated shifts in cell function, manifesting as increased fibrosis and attenuated cell cycle and adipogenic differentiation" [14]. Specifically, collagen signaling pathways showed abnormal over-activation around perivascular CD9+SUSD2+ cells, indicating a disrupted response to endometrial repair in TE, particularly in remodeling of the extracellular matrix [14].

Prolactin Signaling in Endometrial Disorders

scRNA-seq has identified prolactin (PRL) signaling as a key pathway in endometrial pathology. In adenomyosis, a condition characterized by ectopic endometrial tissue in the myometrium, scRNA-seq revealed a distinct epithelial subcluster with enriched PRL receptor (PRLR) expression [15]. This ECM-high epithelial subcluster expanded with disease progression and exhibited exaggerated PRL signaling, which promoted cellular survival and proliferation, contributing to lesion formation [15].

Similarly, scRNA-seq identified a fibroblast subpopulation in adenomyosis patients characterized by strong expression of inflammation-related genes and heightened PRL signaling [15]. PRL treatment of these fibroblasts increased inflammatory cytokine production, establishing a link between hyperactivated PRL signaling and the stromal inflammation characteristic of adenomyosis [15]. These findings were validated in preclinical models, where transgenic overexpression of PRL or pituitary transplantation induced adenomyosis, while PRLR inhibition with the monoclonal antibody HMI-115 ameliorated disease manifestations [15].

Figure 1: Prolactin Signaling Pathway in Adenomyosis. Hyperactivated PRL-PRLR signaling through JAK-STAT pathway drives disease pathogenesis.

Technical Considerations for Endometrial scRNA-seq Studies

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful endometrial scRNA-seq studies. The ideal sample viability should be between 70% and 90%, with intact cell morphology and minimal debris [12]. To achieve this:

Temperature Control: Maintain cold conditions (4°C) during cell extraction to arrest metabolic functions and reduce stress response gene upregulation that can skew data [12]. Endometrial cells held at room temperature rapidly degrade, extruding cellular contents and forming clumps.

Minimize Debris: Filter samples to remove debris, use calcium- and magnesium-free media (e.g., HEPES or Hanks' buffered salt) to prevent aggregation, and optimize centrifugation speeds to avoid over-pelleting [12]. Aggregation should be maintained below 5% for optimal results.

Dissociation Method Selection: Choose enzymatic dissociation protocols specific to endometrial tissue. Commercial enzyme cocktails (e.g., from Miltenyi Biotec) or automated dissociators (gentleMACS Dissociator) can provide reproducible, high-quality single-cell suspensions [12].

For menstrual cycle studies, precise timing of sample collection relative to the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge is essential. Mid-luteal phase samples should be collected on LH days 7-9 for consistent transcriptional profiling [14]. Additionally, careful patient screening is necessary to exclude confounding conditions like endometriosis, leiomyoma, adenomyosis, or polycystic ovary syndrome unless these are the focus of investigation [14].

Computational Analysis Workflow

The computational analysis of endometrial scRNA-seq data typically follows a standardized workflow:

Quality Control and Filtering: Using tools like the Seurat R package, filter out cells with fewer than 1,000 detected genes and less than 10,000 transcripts to remove low-quality cells and debris [14].

Normalization and Variable Feature Selection: Normalize raw counts using the "LogNormalize" method with a scale factor of 10,000, then identify highly variable genes (3,000-4,800 features) for downstream analysis [14].

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) on highly variable genes, then construct shared nearest neighbor graphs using 20-30 principal components. Cell clustering is typically performed at resolution parameters between 0.5-1.0 [14].

Differential Expression and Pathway Analysis: Identify cluster-specific markers using differential expression testing, followed by Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis to determine biological functions of identified clusters [14].

RNA Velocity and Trajectory Inference: Analyze cellular dynamics using scVelo package to predict developmental trajectories and state transitions across menstrual cycle phases [14].

Figure 2: scRNA-seq Workflow for Endometrial Research. Key steps from sample collection to biological validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Endometrial scRNA-seq Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application in Endometrial Research |

|---|---|---|

| Seurat R Package (v5.0.1+) | Single-cell data analysis | Quality control, normalization, clustering, and visualization of endometrial cell populations |

| scVelo Package | RNA velocity analysis | Prediction of cellular trajectories across menstrual cycle phases |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | mRNA molecule barcoding | Accurate transcript quantification by correcting PCR amplification biases |

| 10x Genomics Chromium | High-throughput scRNA-seq | Processing thousands of endometrial cells simultaneously for comprehensive atlas generation |

| Smart-seq2 | Full-length scRNA-seq | Detailed characterization of transcript isoforms in specific endometrial cell types |

| CellChat R Package | Cell-cell communication analysis | Mapping signaling interactions between endometrial cell populations |

| ClusterProfiler (v4.12.2+) | Pathway enrichment analysis | Functional interpretation of phase-specific gene signatures |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting | Cell isolation and enrichment | Separation of specific endometrial populations (e.g., CD9+SUSD2+ cells) for downstream analysis |

| gentleMACS Dissociator | Tissue dissociation | Generation of high-quality single-cell suspensions from endometrial biopsies |

| Mianserin | Mianserin, CAS:24219-97-4, MF:C18H20N2, MW:264.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Phenelzine Sulfate | Phenelzine Sulfate|MAO Inhibitor|CAS 156-51-4 |

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally transformed our understanding of endometrial biology by revealing the phase-specific transcriptional programs underlying the remarkable cyclic regeneration of this tissue. Through the application of scRNA-seq, researchers have identified specialized cell populations, delineated their hormonal regulation, and uncovered pathogenic mechanisms in conditions like thin endometrium and adenomyosis.

The insights gained from these studies highlight the potential of scRNA-seq to advance reproductive medicine by identifying novel therapeutic targets and developing personalized treatment strategies for endometrial disorders. As the technology continues to evolve, with improvements in spatial transcriptomics, multi-omics integration, and computational analysis, we can anticipate even deeper understanding of the intricate hormonal control of endometrial gene expression and its role in reproductive success and disease.

The endometrium, the lining of the uterus, is a quintessential hormone-responsive tissue, undergoing cycles of proliferation, differentiation, and shedding in response to circulating estrogen and progesterone. These dramatic changes are facilitated by precisely orchestrated gene expression programs. Epigenetics—the study of heritable changes in gene function that do not involve changes to the underlying DNA sequence—provides a critical regulatory layer that interprets hormonal signals to control these transcriptional programs [16]. The dynamic and reversible nature of epigenetic mechanisms makes them particularly suited for mediating the cyclic changes in the endometrium. Dysregulation of these processes is increasingly implicated in the pathophysiology of hormone-driven reproductive disorders, including endometriosis, endometrial cancer, and infertility [17] [18]. This review details the core epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—that govern hormonal responses in the endometrium, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Epigenetic Mechanisms and Their Role in Hormone Response

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of a cytosine residue, predominantly within CpG dinucleotides. This modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT3A and DNMT3B establishing de novo methylation patterns and DNMT1 maintaining these patterns during DNA replication [19] [18]. In the context of hormone response, DNA methylation primarily functions to repress gene transcription by preventing transcription factor binding or recruiting proteins that promote chromatin compaction [18].

In the endometrium, global and gene-specific DNA methylation patterns fluctuate across the menstrual cycle, directly influenced by the changing estrogen and progesterone milieu. For instance, promoter hypermethylation can silence genes involved in immunological control and estrogen metabolism, thereby determining the cellular response to hormonal signals [17]. Aberrant DNA methylation is a hallmark of endometrial pathologies; in endometriosis, hypermethylation of genes like HOXA10 disrupts endometrial receptivity, while in endometrial cancer, distinct methylation signatures can predict prognosis and response to therapy [20] [17].

Histone Modifications

Histone modifications are post-translational alterations—including acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation—to the N-terminal tails of histone proteins. These modifications influence chromatin structure by altering the electrostatic charge of histones or creating binding platforms for other proteins. Specific marks are associated with transcriptional activation or repression; for example, H3K27ac and H3K4me3 are robust markers of active promoters and enhancers, while H3K27me3 is linked to transcriptional silencing [21] [22].

During endometrial decidualization, a process driven by progesterone, genome-wide increases in H3K27ac and H3K4me3 are observed at the promoter regions of genes critical for insulin signaling and glucose uptake, facilitating their up-regulation [21]. This demonstrates how histone modifications directly mediate the transcriptional output of hormonal signaling. The balance between histone acetylation and deacetylation, governed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and deacetylases (HDACs), is particularly important for maintaining the open chromatin state required for the expression of hormone-responsive genes.

Non-Coding RNAs (ncRNAs)

Non-coding RNAs are functional RNA molecules that regulate gene expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels without being translated into proteins. The two most studied classes in the context of hormonal response are microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). miRNAs typically bind to the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs, leading to their degradation or translational repression. lncRNAs employ diverse mechanisms, including chromatin modification, transcriptional interference, and serving as molecular "sponges" for miRNAs [23].

In the endometrium, specific ncRNAs are differentially expressed during the window of implantation, a period of peak progesterone response. For example, miR-30b, miR-30d, and miR-494 are involved in establishing endometrial receptivity by fine-tuning the expression of genes critical for embryo implantation [23]. In endometriosis, dysregulated ncRNA expression profiles contribute to disease progression by promoting inflammation, cellular proliferation, and hormone resistance [18]. The presence of stable ncRNAs in bodily fluids like endometrial fluid also highlights their potential as non-invasive biomarkers for endometrial function and disease [23].

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Modifications in Endometrial Hormone Response

| Mechanism | Key Enzymes/Effectors | Functional Outcome | Role in Endometrial Hormone Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, TET proteins | Transcriptional repression, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation | Cyclic, hormone-driven silencing of genes involved in receptivity and inflammation; aberrant patterns in endometriosis and cancer [19] [17] |

| Histone Modifications | HATs, HDACs, KMTs, KDMs | Altered chromatin accessibility (e.g., H3K27ac=active; H3K27me3=repressed) | Genome-wide H3K27ac/H3K4me3 increases during decidualization; mediates progesterone-driven gene expression [21] [22] |

| Non-Coding RNAs | miRNAs (e.g., miR-30b, miR-494), lncRNAs | Post-transcriptional regulation, chromatin remodeling, molecular decoys | Fine-tune gene expression for embryo implantation; dysregulated in endometriosis; potential diagnostic biomarkers [23] [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Epigenetic Analysis

Analyzing DNA Methylation

Bisulfite Sequencing is the gold-standard method for base-resolution mapping of 5-methylcytosine (5mC). The protocol relies on the selective deamination of unmethylated cytosines to uracils by sodium bisulfite treatment, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [24].

- Workflow for Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS):

- DNA Extraction & Fragmentation: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA and fragment it by sonication or enzymatic digestion.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite. This converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines are protected.

- Library Preparation & Amplification: Build a sequencing library from the converted DNA. During subsequent PCR amplification, uracils are amplified as thymines.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the library on a platform such as Illumina.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map sequenced reads to a reference genome. The methylation level at each cytosine is calculated as the percentage of reads reporting a cytosine (vs. thymine) at that position [24].

For cost-effective analyses focused on CpG-rich regions, Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) uses a restriction enzyme (e.g., MspI) to digest and size-select for genomic regions with high CpG density, reducing the required sequencing depth [24].

WGBS/RRBS Experimental Flow

Profiling Histone Modifications

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is the primary method for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites [21] [22].

- Workflow for ChIP-seq:

- Cross-Linking: Treat cells with formaldehyde to covalently link proteins (including histones) to DNA.

- Chromatin Shearing: Use sonication or enzymatic digestion to break the cross-linked chromatin into small fragments (200–600 bp).

- Immunoprecipitation (IP): Incubate the chromatin with a highly specific antibody against the histone modification of interest (e.g., anti-H3K27ac). The antibody-enriched chromatin complexes are pulled down.

- Reverse Cross-Linking & Purification: Heat the IP sample to break the protein-DNA bonds and purify the immunoprecipitated DNA fragments.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Construct a sequencing library from the purified DNA and sequence it.

- Data Analysis: Map the sequenced reads to the reference genome and identify regions with significant enrichment (peaks) compared to a control input sample, indicating the locations of the specific histone mark [21].

Novel techniques like CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN offer advantages over ChIP-seq, including higher resolution, lower background noise, and compatibility with low cell numbers, making them suitable for clinical samples [22] [24].

Investigating Non-Coding RNAs

RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) is a powerful, unbiased method for discovering and quantifying all ncRNAs expressed in a sample.

- Workflow for ncRNA RNA-seq:

- Total RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA, preserving the small RNA fraction.

- Library Preparation: For miRNA analysis, this typically involves size-selection of small RNAs, followed by adapter ligation and reverse transcription. For lncRNA analysis, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion is often performed to enrich for other RNA species.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the libraries.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map reads to the genome, quantify expression levels, and identify differentially expressed known and novel ncRNAs. Target prediction algorithms and pathway analysis are then used to infer biological functions [23].

Table 2: Key Methodologies in Epigenetic Research

| Method | Target | Resolution | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS [24] | 5-methylcytosine | Base-pair | Gold standard; comprehensive genome coverage | High cost; cannot distinguish 5mC from 5hmC |

| RRBS [24] | CpG-rich regions | Base-pair | Cost-effective; focused on regulatory regions | Incomplete genome coverage; sequence bias |

| ChIP-seq [21] [22] | Histone modifications, TFs | ~200 bp | Genome-wide binding/ modification profiles | Requires high-quality antibodies; high cell input |

| CUT&Tag [22] | Histone modifications, TFs | Single-cell | Low background; works with low cell numbers | Still a relatively new technique |

| RNA-seq [23] | ncRNAs (miRNA, lncRNA) | Single transcript | Discovery and quantification in one assay | Complex bioinformatics; high depth needed for rare transcripts |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Epigenetic Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite [24] | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil | Essential pre-treatment for BS-seq, WGBS, and RRBS to determine methylation status. |

| MspI Restriction Enzyme [24] | Cuts at CCGG sites regardless of methylation | Used in RRBS to digest and enrich for CpG-rich genomic regions. |

| Anti-H3K27ac Antibody [21] | Specifically binds to H3K27ac epitope | Immunoprecipitation step in ChIP-seq to pull down DNA associated with active enhancers and promoters. |

| Formaldehyde [22] | Reversible cross-linking of proteins to DNA | Fixation step in ChIP-seq to preserve in vivo protein-DNA interactions. |

| DNMT Inhibitors (e.g., Decitabine) [19] [22] | Inhibits DNA methyltransferases | Experimental tool to demethylate DNA and study the functional consequences of loss of methylation. |

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Vorinostat) [19] [22] | Inhibits histone deacetylases | Experimental tool to increase global histone acetylation and study its effect on gene expression. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Epigenetic Editors [19] | Targeted epigenetic modification | dCas9 fused to DNMT3A (for methylation) or p300 (for acetylation) allows precise editing of specific loci. |

| Phenglutarimid | Phenglutarimid, CAS:1156-05-4, MF:C17H24N2O2, MW:288.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| S3QEL-2 | S3QEL-2, MF:C19H25N5, MW:323.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

The following diagram integrates the core epigenetic mechanisms into a conceptual pathway of hormonal signaling in the endometrium, illustrating how estrogen and progesterone signals are transduced into epigenetic and transcriptional changes.

Hormonal Regulation via Epigenetics

The window of implantation (WOI) represents a critical, transient period of endometrial maturation during which the uterine lining becomes receptive to embryonic implantation. This period, generally occurring between days 19-21 of a typical 28-day menstrual cycle, is characterized by a specific molecular signature that enables the trophectoderm of the blastocyst to attach to endometrial epithelial cells and subsequently invade the endometrial stroma [25]. The clinical significance of accurately identifying the WOI is profound, as suboptimal endometrial receptivity and altered embryo-endometrial crosstalk account for approximately two-thirds of human implantation failures [26].

Molecular assessment of endometrial receptivity has revealed that a significant proportion of women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART) exhibit displaced WOI. Recent large-scale studies demonstrate that approximately 34.18% (771/2256) of subfertile patients show WOI displacement, with 25.0% presenting with pre-receptive endometrium and 9.2% with post-receptive endometrium at the expected receptivity timeframe [27]. The precision of embryo transfer timing relative to the WOI significantly impacts ART outcomes, with transfers deviating more than 12 hours from the optimal window showing substantially reduced pregnancy rates (23.08% vs 44.35%, p < 0.001) and approximately twofold increase in pregnancy loss [27]. These findings underscore the critical importance of precise WOI determination for successful embryo implantation and pregnancy establishment.

Molecular Biomarkers of Endometrial Receptivity

Transcriptomic Signatures

The molecular basis of endometrial receptivity is characterized by complex gene expression patterns that transform the endometrium into a receptive state. Transcriptomic analyses have identified specific gene signatures that reliably predict receptivity status across different patient populations and cycle types. Several molecular tests have been developed based on these signatures, each utilizing distinct biomarker panels and technological platforms.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Endometrial Receptivity Testing Platforms

| Test Name | Technology Platform | Biomarker Number | Reported Accuracy | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER Map [27] | High-throughput RT-qPCR | Not specified | Significant improvement in pregnancy rates (p<0.001) | Identifies WOI displacement in 34.18% of subfertile patients |

| rsERT [28] | RNA-Sequencing | 175 genes | 98.4% (cross-validation) | Improved pregnancy rates in RIF patients (50.0% vs 23.7%) |

| beREADY [29] | TAC-seq | 72 genes (57 biomarkers + 11 WOI genes + 4 housekeepers) | 98.8% (cross-validation) | Detected displaced WOI in 15.9% of RIF patients vs 1.8% in fertile women |

| ERA [30] | Microarray | 238 genes | Established clinical utility | One of the first clinical transcriptomic tests for receptivity |

The molecular signature of receptivity involves coordinated expression changes across multiple gene families. Key functional categories include:

- Morphogenesis Factors: Genes involved in tissue remodeling and structural preparation for implantation

- Immunomodulators: Factors that establish maternal immune tolerance to the semi-allogeneic embryo

- Cell Adhesion Molecules: Mediators of embryo-endometrial attachment and interaction

- Transcription Factors: Regulators that coordinate the receptivity network

- Metabolic Pathway Genes: Enzymes supporting the bioenergetic demands of implantation [27] [30]

Recent research has revealed that the WOI timeframe exhibits considerable individual variability, with receptive endometria detected as early as 2.5 days after progesterone administration (P4 + 2.5) and up to 8 days after progesterone (P4 + 8) in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) cycles [27]. This variability highlights the limitations of standardized progesterone protocols and supports the need for personalized receptivity assessment.

Beyond Gene-Level Expression: Splicing and Isoform Variations

Emerging evidence indicates that transcript isoform-level and RNA splicing variations provide an additional layer of regulation in endometrial receptivity that is not detectable through conventional gene-level expression analysis. A 2025 study integrating large endometrial transcriptomic datasets (n=206) identified significant RNA splicing and transcript isoform-level changes across the menstrual cycle and in endometriosis [31].

Notably, when comparing mid-proliferative (MP) and mid-secretory (MS) phases, transcript-level analyses revealed that 24.5% of genes with differential transcript usage (DTU) and 27.0% of genes with differential splicing (DS) would not have been detected by gene-level expression analysis alone [31]. These splicing-specific changes affect biologically meaningful pathways including hormone regulation and cell growth, providing new insights into the molecular complexity of endometrial receptivity.

In endometriosis cases, specific splicing alterations have been identified, including decreased exon 4-skipping in the ZNF217 gene (ΔPSI = -6.4%), which is involved in estrogen receptor α-mediated signal transduction [31]. This finding demonstrates how genetic regulation of splicing may contribute to endometriosis-related implantation failure, potentially opening new avenues for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Methodological Approaches for Transcriptomic Analysis

Experimental Workflow for Endometrial Receptivity Assessment

The standard protocol for endometrial receptivity assessment involves a coordinated process from sample collection through computational analysis. The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for transcriptomic profiling of endometrial receptivity:

Sample Collection and Processing Protocols

Patient Selection and Endometrial Biopsy:

- Timing: Endometrial biopsies are typically performed during the mid-secretory phase (LH+7 in natural cycles or P+5 in hormone replacement cycles) [28]

- Validation: Timing should be corroborated with histological evaluation using Noyes' criteria and/or LH peak measurements [29] [32]

- Exclusion Criteria: Standard protocols exclude patients with endometrial pathologies (polyps, adhesions, endometritis), hydrosalpinx, endocrine disorders, or active infections [32]

RNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Extraction Method: Use of commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kits) following manufacturer's protocol [32]

- Quality Assessment: RNA integrity evaluation using Agilent Bioanalyzer; concentration measurement via NanoDrop spectrophotometer [33]

- Inclusion Threshold: Samples must meet minimum RNA quality standards (e.g., RIN > 7) for reliable transcriptomic analysis

Sequencing and Computational Analysis

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- rRNA Depletion: Ribosomal RNA removal from total RNA to enrich for mRNA transcripts

- Library Construction: Strand-specific library preparation using fragmented mRNA [33]

- Sequencing Platforms: Various platforms including BGISEQ, Illumina, or other high-throughput systems generating typically 6 Gb of data per sample [33]

Bioinformatic Processing:

- Quality Control: FastQC, Trim Galore, or Cutadapt for raw read quality assessment and adapter trimming

- Alignment and Quantification: STAR alignment to reference genome followed by gene-level quantification using StringTie and RSEM [33]

- Normalization: Expression level normalization using FPKM and TPM metrics for cross-sample comparison

Differential Expression Analysis:

- Statistical Methods: DESeq2 package in R for identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with FDR < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5 [33]

- Enrichment Analysis: Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment using clusterProfiler package to identify biological processes associated with receptivity [33]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Endometrial Receptivity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kits, RNA-easy isolation reagent (Vazyme) | Total RNA isolation from endometrial tissue | Ensure RNA integrity (RIN >7) for reliable sequencing |

| Library Prep Kits | Strand-specific library preparation kits | Construction of sequencing libraries | rRNA depletion crucial for transcriptome coverage |

| Sequencing Platforms | BGISEQ, Illumina platforms | High-throughput transcriptome sequencing | Typically generate ~6 Gb data per sample [33] |

| Computational Tools | FastQC, Trim Galore, Cutadapt, STAR, DESeq2, clusterProfiler | Quality control, alignment, differential expression, and pathway analysis | R/Bioconductor environment standard for analysis |

| Reference Datasets | GEO datasets (GSE111974, GSE71331, GSE58144, GSE106602) [32] | Validation and meta-analysis | Enable cross-study validation and biomarker discovery |

| Sacubitril sodium | Sacubitril sodium, CAS:149690-05-1, MF:C24H28NNaO5, MW:433.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Scrip | Scrip, CAS:94162-23-9, MF:C54H77N13O9, MW:1052.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Molecular Heterogeneity and Clinical Subtypes

Recurrent Implantation Failure Subtypes

Recent research has revealed that recurrent implantation failure (RIF) exhibits distinct molecular subtypes with different underlying pathophysiologies. A 2025 multi-omics study identified two biologically distinct endometrial subtypes of RIF:

- Immune-Driven Subtype (RIF-I): Characterized by enrichment of immune and inflammatory pathways (IL-17 and TNF signaling, p < 0.01) with increased infiltration of effector immune cells [32]

- Metabolic-Driven Subtype (RIF-M): Marked by dysregulation of oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid metabolism, steroid hormone biosynthesis, and altered expression of the circadian clock gene PER1 [32]

These subtypes demonstrate the heterogeneous nature of RIF pathogenesis and highlight the potential for personalized therapeutic approaches. The MetaRIF classifier developed to distinguish these subtypes achieved high accuracy in independent validation cohorts (AUC: 0.94 and 0.85) [32].

Endometrial-Embryo Cross-Talk Mechanisms

Successful implantation requires sophisticated bi-directional communication between the endometrium and embryo during the WOI. The following diagram illustrates key molecular mechanisms governing this cross-talk:

Key molecular players in this cross-talk include:

- Cytokines and Growth Factors: LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor) promotes decidualization, pinopod expression, and trophoblast differentiation [25]; HB-EGF (heparin-binding epidermal growth-like factor) triggers initial communication between blastocyst and endometrium [25]

- Adhesion Molecules: Integrins (particularly β3 integrin) and selectins facilitate strong connection between blastocyst and endometrium during adhesion [25]

- Extracellular Vesicles: Bi-directional exchange of extracellular vesicles between endometrial cells and embryo facilitates synchronous molecular programming [26]

- Imm Modulators: HLA-G expressed by invading trophoblasts modulates cytokine secretion to maintain local immunosuppressive state [25]

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances in understanding the molecular signature of endometrial receptivity, several challenges remain in translating these findings to clinical practice:

- Technical Standardization: Variability in sampling techniques, RNA processing methods, and computational pipelines across centers [26]

- Spatial Heterogeneity: Current sampling from single endometrial sites may not capture molecular patterns across potential implantation sites [26]

- Dynamic Monitoring: Static molecular assessments fail to capture the temporal dynamics of receptivity establishment [26]

- Clinical Validation: Need for larger randomized controlled trials to validate the efficacy of personalized embryo transfer based on molecular receptivity testing [28]

Future research directions focus on integrating multi-omics approaches (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to develop more comprehensive receptivity signatures [30], utilizing single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to resolve cellular heterogeneity [33], and developing non-invasive diagnostic methods using uterine fluid or exosomal biomarkers [30]. Artificial intelligence-driven models show particular promise, with some machine learning approaches already achieving AUC > 0.9 in predicting receptivity status [30].

The continued elucidation of molecular mechanisms governing endometrial receptivity will enable more precise personalization of fertility treatments, potentially transforming outcomes for patients experiencing implantation failure and advancing the field of reproductive medicine.

Decidualization, the transformation of endometrial stromal cells (ESCs) into specialized decidual stromal cells (DSCs), represents a pivotal genomic reprogramming event essential for embryo implantation and the establishment of pregnancy. This process is a fundamental component of the hormonal control of endometrial gene expression, driven primarily by the postovulatory rise in progesterone levels and local cyclic AMP (cAMP) production [34] [35]. Occurring in species with invasive hemochorial placentae, decidualization enables the endometrium to acquire a receptive phenotype, preventing immunological rejection of the semi-allogeneic embryo and fostering its development [36] [37]. The profound genetic, epigenetic, and proteomic changes during this transition are orchestrated by a complex hormonal cascade, culminating in the brief window of implantation (WOI) [29]. Disruptions in this meticulously regulated process are implicated in significant reproductive disorders, including recurrent implantation failure (RIF), recurrent pregnancy loss, and endometriosis [36] [32] [35]. This review examines the molecular mechanisms, metabolic reprogramming, and experimental methodologies underlying decidualization, framing them within the broader context of hormonal regulation of endometrial gene expression.

Molecular Mechanisms and Genomic Reprogramming

Hormonal Signaling and Transcriptional Regulation

The initiation and progression of decidualization are governed by a well-defined hormonal sequence. Following ovulation, progesterone binding to its receptor (PGR) activates downstream signaling cascades, including the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, which are critical for the expression of decidualization markers [34] [35]. Concurrently, local cAMP accumulation acts as a potent intracellular second messenger, synergizing with progesterone to drive the differentiation of fibroblast-like ESCs into rounded, secretory epithelioid DSCs [34] [37].

Key transcription factors, including HAND2, CEBPB, and EGR1, are upregulated during this process and execute the genomic reprogramming necessary for the decidual phenotype [35]. HAND2, a downstream effector of stromal progesterone signaling, is particularly crucial as it suppresses epithelial cell proliferation via fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), facilitating appropriate endometrial remodeling [35]. Recent research has highlighted the role of epigenetic regulators in this process. Menin, a subunit of the H3K4 methyltransferase complex, facilitates histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) at promoters of genes essential for decidualization, such as SFRP2 and DKK1 (negative regulators of the WNT pathway) [35]. Reduced Menin expression in the endometrial stroma of RIF patients is associated with impaired decidualization and aberrant WNT signaling activation, underscoring the importance of epigenetic regulation in endometrial receptivity [35].

Oxidative Stress Resistance

Decidualizing stromal cells must tolerate high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammation associated with cellular reprogramming and deep placentation [36]. Successful decidualization involves the activation of robust antioxidant defense mechanisms. Key molecular players, including SLC40A1 and GPX4, coordinate iron balance and mitigate lipid peroxidation, thereby conferring cellular resilience to oxidative stress [36]. The resistance to oxidative stress is a hallmark of strong, progesterone-driven decidualization in certain eutherian mammals, creating a specialized maternal-fetal interface that supports pregnancy establishment [36].

Table 1: Key Molecular Regulators of Decidualization

| Regulator | Function | Mechanism of Action | Associated Reproductive Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menin (MEN1) | Epigenetic regulator | Catalyzes H3K4me3; represses WNT pathway via SFRP2/DKK1 | Recurrent Implantation Failure (RIF) [35] |

| HAND2 | Transcription factor | Suppresses epithelial proliferation via FGFs; stromal progesterone effector | Impaired endometrial receptivity [35] |

| SLC40A1 | Iron transporter | Coordinates iron balance to mitigate oxidative stress | Impaired decidualization [36] |

| GPX4 | Antioxidant enzyme | Reduces lipid peroxidation; confers oxidative stress resistance | Early pregnancy loss [36] |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter | Mediates glucose uptake; upregulated by progesterone/PI3K-AKT | Decidualization deficiency in hyperinsulinemia/PCOS [34] |

Metabolic Reprogramming in Decidualization

Glucose Metabolism and the Warburg Effect

Decidualization is an energy-intensive process accompanied by significant metabolic reprogramming [34] [37]. Differentiating stromal cells exhibit characteristics of the Warburg effect, preferentially producing lactate from glucose via glycolysis even under normoxic conditions, rather than through oxidative phosphorylation [34]. This shift to glycolysis provides rapidly available energy and biomass to meet the high demands of cellular differentiation and function.

Glucose uptake, mediated by glucose transporters (GLUTs), is the critical first step in this metabolic shift. Among the GLUT family members expressed in the human endometrium, GLUT1 (SLC2A1) is dynamically regulated during the menstrual cycle, showing significant upregulation in the mid-secretory phase that is further enhanced during decidualization [34]. Progesterone facilitates GLUT1 expression through PGR binding and downstream activation of IRS2, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT pathways [34]. Epigenetic modifications, such as histone H3 lysine-27 acetylation (H3K27ac), have also been implicated in GLUT1 upregulation [34]. Conversely, miR-140-5p downregulates GLUT1, leading to reduced glucose uptake, impaired decidualization, and increased apoptosis [34]. Other transporters, including GLUT3, GLUT4, GLUT8, and SGLT1, also contribute to glucose homeostasis in the endometrium, with dysregulation linked to reproductive pathologies such as PCOS and RIF [34].

Once inside the cell, glucose is metabolized through glycolysis, and key enzymes in this pathway are critically involved in decidualization:

- Hexokinase 2 (HK2): The first rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis, HK2 expression is upregulated during decidualization, stimulating glucose uptake and lactate production. Its downregulation via miR-6887-3p suppresses glycolysis and impairs decidualization [34].

- Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK1): This enzyme catalyzes the conversion of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP). Steroid receptor coactivator-2 (SRC-2) accelerates glycolytic flux by inducing PFKFB3, which allosterically activates PFK1. FBP accumulation in DSCs promotes decidualization, trophoblast invasion, and maternal-fetal tolerance [34].

Table 2: Glucose Metabolism in Decidualization

| Metabolic Component | Role in Decidualization | Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| GLUT1 | Primary glucose uptake transporter; expression increases during decidualization | Upregulated by progesterone, PI3K/AKT, H3K27ac; downregulated by miR-140-5p [34] |

| HK2 | Commits glucose to glycolysis; increased activity supports Warburg effect | Downregulated by miR-6887-3p; knockdown impairs decidualization [34] |

| PFK1/PFKFB3 | Rate-limiting step glycolysis; FBP accumulation promotes implantation | Activated by SRC-2 via PFKFB3 induction [34] |

| Warburg Effect | Metabolic shift to glycolysis for rapid ATP and biomass production | Characterized by enhanced extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) [34] [37] |

Metabolic Heterogeneity and Alternative Energy Pathways

Beyond glucose metabolism, decidualization involves reprogramming of amino acid and sphingolipid metabolism [37]. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revealed significant metabolic heterogeneity among decidual cells, with subpopulations exhibiting distinct metabolic activities correlating with differentiation maturity and cellular function [37]. For instance, decidual cells with high metabolic activity demonstrate greater cellular communication potential [37]. Lipids provide essential energy and raw materials for stromal-decidual transformation, and disruption of sphingolipid metabolism can lead to uterine vascular bed instability and impaired decidualization [37]. This metabolic heterogeneity underscores the complexity of energy management during endometrial reprogramming.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Decidualization Models

The gold standard for studying human decidualization in vitro involves isolating and differentiating primary human endometrial stromal cells (hESCs). The following protocol details a typical experimental setup for inducing and validating decidualization:

Protocol: In Vitro Decidualization of Primary hESCs

- Cell Culture: Primary hESCs are isolated from endometrial biopsies obtained during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. Cells are cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 10% charcoal-striped fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

- Decidualization Induction: Upon reaching 70-80% confluence, cells are treated with a decidualization cocktail. A standard formulation includes:

- 1 μM Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) or other progestin.

- 0.5 mM cAMP analog (e.g., 8-Br-cAMP).

- 10 nM Estradiol (E2). The medium containing the decidualization stimuli is replaced every 2-3 days for 6-12 days to achieve full differentiation [35].

- Functional Validation: Successful decidualization is confirmed by morphological and molecular markers:

- Morphological Change: Differentiating cells transition from elongated, fibroblastic shapes to larger, rounded epithelioid shapes with expanded cytoplasm. F-actin staining (e.g., with phalloidin) can visualize this cytoskeletal reorganization [35].

- Molecular Markers: The most widely used markers are the secreted products:

- Prolactin (PRL): Secreted levels measured by ELISA in the culture supernatant. A significant increase (often 10-100 fold) is observed in successfully decidualized cells [35].

- Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-1 (IGFBP-1): mRNA expression measured by qRT-PCR and/or protein levels by Western Blot or immunofluorescence [35].

- Proliferation Assay: Decidualization is associated with a switch from proliferation to differentiation. Assays like EdU incorporation or CCK-8 should show reduced proliferation in decidualized cells compared to undifferentiated controls [35].

Advanced Models and Omics Technologies

- Genetic Manipulation: Lentivirus-mediated knockdown (e.g., of MEN1) or overexpression is used to investigate gene function. Transfected cells are selected with antibiotics (e.g., puromycin) prior to decidualization induction [35].

- Assembloids: To study stromal-epithelial communication, researchers co-culture decidualizing stromal cells with endometrial epithelial organoids. These 3D models, or "assembloids," better recapitulate the tissue microenvironment and allow for the study of paracrine signaling, such as the HAND2-FGFs-FGFR axis [35].