Machine Learning in Biomarker Discovery: From Data to Clinical Impact

This article provides a comprehensive overview of machine learning (ML) applications in biomarker discovery for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Machine Learning in Biomarker Discovery: From Data to Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of machine learning (ML) applications in biomarker discovery for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational need for ML in analyzing complex omics data, details practical methodological approaches and successful applications, addresses critical challenges like overfitting and data quality, and examines rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current methodologies and real-world case studies, this guide aims to bridge the gap between computational innovation and robust, clinically translatable biomarker development.

The New Frontier: Why Machine Learning is Revolutionizing Biomarker Research

The rapid evolution of high-throughput technologies has generated an unprecedented deluge of biological data, creating both opportunities and challenges for biomarker discovery. Multi-omics strategies, which integrate genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, have revolutionized our approach to understanding complex diseases like cancer [1]. This integrative approach provides a comprehensive view of molecular networks that govern cellular life, enabling the identification of robust biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic decision-making in personalized oncology [1]. The inherent complexity of biological systems means that single-omics approaches often fail to capture the complete picture of disease mechanisms, making multi-omics integration not merely advantageous but essential for meaningful biological inference [1] [2].

The transition from single-omics to multi-omics analysis represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research. Where traditional methods focused on single genes or proteins, multi-omics integration can reveal complex interactions and emergent properties that remain invisible when examining molecular layers in isolation [2]. This holistic perspective is particularly crucial for biomarker discovery, as biomarkers identified through multi-omics strategies demonstrate greater clinical utility and reliability compared to those derived from single-omics approaches [1]. The challenge now lies in developing sophisticated computational frameworks capable of navigating this high-dimensional landscape to extract biologically and clinically meaningful insights.

Analytical Frameworks and Computational Strategies

Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

The integration of diverse omics datasets requires sophisticated computational strategies that can be broadly categorized into three main paradigms: early, intermediate, and late integration [3]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different research contexts and questions.

Early integration involves combining raw data from different omics layers at the beginning of the analytical pipeline. This strategy can capture complex correlations and relationships between different molecular layers but may introduce significant noise and computational challenges [3]. Intermediate integration processes each omics dataset separately initially, then combines them at the feature selection, extraction, or model development stage. This balanced approach maintains the unique characteristics of each data type while enabling the identification of cross-omics patterns [3]. Late integration, also known as vertical integration, analyzes each omics dataset independently and combines the results at the final interpretation stage. This method preserves dataset-specific signals but may miss important inter-omics relationships [3].

The selection of an appropriate integration strategy depends on multiple factors, including research objectives, data characteristics, computational resources, and the specific biological questions under investigation. A comprehensive understanding of the strengths and limitations of each approach is fundamental to effective multi-omics data analysis [3].

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have emerged as powerful tools for multi-omics integration, capable of identifying complex, non-linear patterns within high-dimensional datasets that traditional statistical methods often miss [1] [2]. These approaches have demonstrated particular utility in biomarker discovery, where they can integrate diverse data types including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, imaging, and clinical records [2].

Deep learning architectures, such as those implemented in tools like Flexynesis, provide flexible frameworks for bulk multi-omics data integration [4]. Flexynesis streamlines data processing, feature selection, and hyperparameter tuning while supporting multiple task types including regression, classification, and survival modeling [4]. This flexibility is especially valuable in precision oncology, where accurate decision-making depends on integrating multimodal molecular information [4]. The toolkit's modular design allows researchers to choose from various deep learning architectures or classical machine learning methods through a standardized interface, making advanced computational approaches more accessible to users with varying levels of computational expertise [4].

Beyond conventional ML/DL approaches, genetic programming has shown promise for optimizing multi-omics integration and feature selection. This evolutionary algorithm-based approach can identify robust biomarkers and improve predictive accuracy in survival analysis, as demonstrated in breast cancer research where it achieved a concordance index (C-index) of 67.94 on test data [3]. Similarly, adaptive integration frameworks like MOGLAM and MoAGL-SA employ dynamic graph convolutional networks with feature selection to generate high-quality omic-specific embeddings and identify important biomarkers [3].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method | Cancer Type | Application | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepMO | Breast Cancer | Subtype Classification | 78.2% Accuracy | [3] |

| DeepProg | Liver/Breast Cancer | Survival Prediction | C-index: 0.68-0.80 | [3] |

| Adaptive Multi-omics Framework | Breast Cancer | Survival Analysis | C-index: 67.94 (Test) | [3] |

| SeekInCare | Multiple Cancers | Early Detection | 60.0% Sensitivity, 98.3% Specificity | [5] |

| MOFA+ | Pan-Cancer | Latent Factor Modeling | N/A (Interpretability Focus) | [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery Pipeline

This protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow for biomarker discovery from multi-omics data, incorporating quality control, integration, and validation steps essential for generating clinically relevant findings.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multi-omics datasets (e.g., from TCGA, CPTAC, CCLE)

- High-performance computing infrastructure

- Bioinformatics software packages (e.g., Flexynesis, MOFA+)

- Statistical analysis environment (R, Python)

Procedure:

Data Acquisition and Curation

Quality Control and Preprocessing

- Perform platform-specific quality assessment for each omics dataset

- Apply normalization procedures to address technical variability

- Handle missing values using appropriate imputation methods

- Filter low-quality samples and features with minimal expression/variance

Data Integration and Feature Selection

- Select integration strategy (early, intermediate, or late) based on research question

- Implement dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, UMAP, autoencoders)

- Apply feature selection algorithms to identify informative molecular features

- Utilize genetic programming or ML-based methods for optimized feature selection [3]

Predictive Model Development

- Partition data into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70/15/15 split)

- Train ML/DL models using appropriate architectures (e.g., fully connected networks, graph convolutional networks)

- Optimize hyperparameters through cross-validation

- Regularize models to prevent overfitting

Biomarker Validation and Interpretation

- Evaluate model performance on independent test sets using relevant metrics (AUC, C-index)

- Assess clinical utility through survival analysis or treatment response prediction

- Perform biological interpretation via pathway enrichment and network analysis

- Validate findings in external cohorts when available

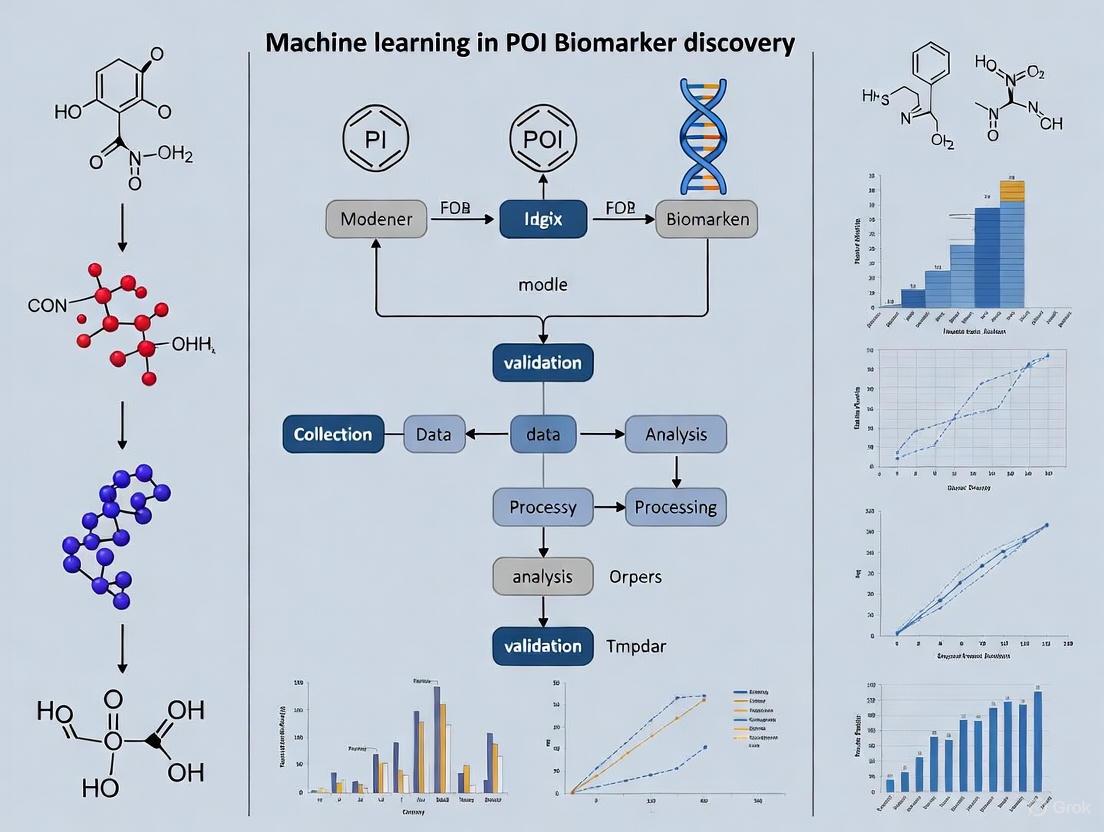

Workflow Visualization

Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive pipeline for biomarker discovery from multi-omics data, highlighting key stages from data collection to clinical application and the three primary integration strategies.

Applications in Precision Oncology

Clinically Validated Multi-Omics Biomarkers

Multi-omics approaches have yielded numerous clinically actionable biomarkers that are transforming precision oncology. These biomarkers operate at different molecular levels and have been validated through large-scale studies and clinical trials.

The tumor mutational burden (TMB), validated in the KEYNOTE-158 trial, has received FDA approval as a predictive biomarker for pembrolizumab treatment across various solid tumors [1]. Similarly, transcriptomic signatures such as Oncotype DX (21-gene) and MammaPrint (70-gene) have demonstrated utility in tailoring adjuvant chemotherapy decisions for breast cancer patients, as evidenced by the TAILORx and MINDACT trials [1]. Proteomic analyses through initiatives like the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) have identified functional subtypes and druggable vulnerabilities in ovarian and breast cancers that were missed by genomic analyses alone [1].

Epigenomic markers also show significant clinical promise. MGMT promoter methylation status serves as a established predictive biomarker for temozolomide response in glioblastoma patients [1]. Furthermore, DNA methylation-based multi-cancer early detection assays, such as the Galleri test, are currently under clinical evaluation and represent the next frontier in cancer screening [1].

Table 2: Clinically Validated Multi-Omics Biomarkers in Oncology

| Biomarker | Omics Layer | Cancer Type | Clinical Application | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMB | Genomics | Multiple Solid Tumors | Immunotherapy Response | FDA-Approved (KEYNOTE-158) |

| Oncotype DX | Transcriptomics | Breast Cancer | Chemotherapy Decision | TAILORx Trial |

| MammaPrint | Transcriptomics | Breast Cancer | Chemotherapy Decision | MINDACT Trial |

| MGMT Methylation | Epigenomics | Glioblastoma | Temozolomide Response | Standard of Care |

| 2-HG | Metabolomics | Glioma | Diagnosis & Mechanistic | Clinical Validation |

| SeekInCare | Multi-Omics | 27 Cancer Types | Early Detection | Retrospective & Prospective Studies [5] |

Blood-Based Multi-Omics Early Detection

Blood-based multi-omics tests represent a promising approach for non-invasive cancer early detection. The SeekInCare test exemplifies this strategy, incorporating multiple genomic and epigenetic hallmarks including copy number aberration, fragment size, end motif, and oncogenic virus detection via shallow whole-genome sequencing of cell-free DNA, combined with seven protein tumor markers from a single blood draw [5].

This multi-omics approach addresses cancer heterogeneity by targeting multiple biological hallmarks simultaneously, overcoming limitations of single-analyte tests. In retrospective validation involving 617 patients with cancer and 580 individuals without cancer across 27 cancer types, SeekInCare achieved 60.0% sensitivity at 98.3% specificity, with an area under the curve of 0.899 [5]. The test demonstrated increasing sensitivity with disease progression: 37.7% at stage I, 50.4% at stage II, 66.7% at stage III, and 78.1% at stage IV [5]. Prospective evaluation in 1,203 individuals receiving the test as a laboratory-developed test further confirmed its performance with 70.0% sensitivity at 95.2% specificity [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Successful navigation of high-dimensional omics landscapes requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table details essential solutions for multi-omics biomarker discovery research.

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Biomarker Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexynesis | Deep Learning Toolkit | Bulk multi-omics integration | Drug response prediction, cancer subtype classification, survival modeling [4] |

| TCGA | Data Repository | Curated multi-omics data | Provides validated datasets for model training and validation [1] |

| CPTAC | Data Repository | Proteogenomic data | Correlates genomic alterations with protein expression [1] |

| MOFA+ | Statistical Tool | Bayesian group factor analysis | Identifies latent factors across omics datasets; interpretable integration [3] |

| DriverDBv4 | Database | Multi-omics driver characterization | Integrates genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data [1] |

| Genetic Programming | Algorithm | Adaptive feature selection | Optimizes multi-omics integration and identifies robust biomarker panels [3] |

| SeekInCare | Analytical Method | Blood-based multi-omics analysis | Multi-cancer early detection using combined genomic and proteomic markers [5] |

| Tunaxanthin | Tunaxanthin, CAS:12738-95-3, MF:C40H56O2, MW:568.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Sinocrassoside C1 | Sinocrassoside C1, MF:C27H30O16, MW:610.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Integration Methodologies

Comparative Analysis of Integration Techniques

The selection of an appropriate integration methodology significantly impacts biomarker discovery outcomes. Different computational approaches offer varying strengths in handling data complexity, scalability, and interpretability.

Deep learning methods excel at capturing non-linear relationships and complex interactions between molecular layers. Tools like Flexynesis provide architectures for both single-task and multi-task learning, enabling simultaneous prediction of multiple clinical endpoints such as drug response, cancer subtype, and survival probability [4]. This multi-task approach is particularly valuable in clinical settings where multiple outcome variables may have missing values for some samples [4].

In contrast, classical machine learning methods like Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, and XGBoost sometimes outperform deep learning approaches, especially with limited sample sizes [4]. These methods often provide greater interpretability through feature importance metrics, facilitating biological validation of discovered biomarkers.

Statistical approaches like MOFA+ employ Bayesian group factor analysis to learn shared low-dimensional representations across omics datasets [3]. These models infer latent factors that capture key sources of variability while using sparsity-promoting priors to distinguish shared from modality-specific signals. This explicit modeling of factor structure typically requires less training data than neural networks and offers enhanced interpretability by linking latent factors to specific molecular features [3].

Cross-Omics Relationship Visualization

Multi-Omics Integration Modalities: This diagram illustrates the three primary computational approaches for multi-omics data integration and their pathways to clinical application in biomarker discovery.

The navigation of high-dimensional omics landscapes represents both a formidable challenge and unprecedented opportunity in biomarker discovery. As multi-omics technologies continue to evolve, generating increasingly complex and voluminous datasets, the development of sophisticated computational frameworks becomes increasingly critical. The integration of machine learning and deep learning approaches with multi-omics data has demonstrated significant potential for identifying robust, clinically actionable biomarkers across diverse cancer types and other complex diseases. Future advancements will likely focus on refining integration methodologies, improving model interpretability, and establishing standardized validation frameworks to ensure the translation of computational discoveries into clinically useful tools that enhance patient care and outcomes.

The pursuit of biomarkers—measurable indicators of biological processes, pathological states, or therapeutic responses—faces unprecedented challenges in the era of high-dimensional biology [6]. Conventional statistical methods, including t-tests and ANOVA, which long served as the backbone of biomedical research, are increasingly inadequate for analyzing complex omics datasets [7]. These traditional approaches assume specific data distributions (e.g., normality), struggle with the scale of millions of molecular features, and cannot capture nonlinear relationships inherent in biological systems [7] [8]. The limitations of these methods become critically apparent in biomarker discovery for precision medicine, where researchers must integrate genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and clinical data to identify reproducible signatures [8]. This analytical gap has catalyzed the adoption of machine learning (ML) approaches capable of handling data complexity, heterogeneity, and volume that defy conventional parametric methods [7] [9].

Table 1: Comparison Between Traditional Statistical and Machine Learning Approaches

| Analytical Characteristic | Traditional Statistics | Machine Learning Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Data distribution assumptions | Requires normality assumption | Distribution-free; handles diverse data types |

| Multiple testing correction | Struggles with extreme dimensionality | Embedded regularization and feature selection |

| Nonlinear relationships | Limited capture of complex interactions | Models complex, nonlinear patterns |

| Handling missing data | Often requires complete cases | Multiple imputation and robust handling |

| Integration of multi-omics data | Limited capacity for data fusion | Specialized architectures for multimodal data |

| Model interpretability | High inherent interpretability | Requires explainable AI (XAI) techniques |

Key Limitations of Conventional Statistical Methods

Dimensionality and Multiple Testing Challenges

Conventional statistical methods encounter fundamental limitations when applied to omics-scale data where the number of features (p) vastly exceeds the number of samples (n) [7]. In genome-wide association studies or transcriptomic analyses, researchers must test millions of hypotheses simultaneously, creating a massive multiple testing burden that dramatically reduces statistical power after correction [8]. This p>>n problem renders traditional univariate analyses ineffective for identifying subtle but biologically meaningful signals amidst overwhelming dimensionality [7]. Furthermore, biological heterogeneity introduces additional complexity that conventional methods struggle to accommodate, as they cannot efficiently model the intricate interactions between genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that collectively influence disease risk and treatment response [9].

Distributional and Complexity Constraints

Parametric statistical tests rely on assumptions that are frequently violated in omics data [7]. Gene expression data often exhibits skewness, kurtosis, and outliers that violate normality assumptions, while natural biological processes like gene duplication and selection create complex distributions that defy simple parametric description [7]. Additionally, conventional methods cannot adequately capture the nonlinear relationships and higher-order interactions that characterize complex biological systems, potentially missing critical biomarkers that operate in coordinated networks rather than isolation [8]. The limitations extend beyond analytical considerations to practical implementation, as large omics datasets with potentially millions of features present computational challenges that exceed the capabilities of many conventional statistical packages [7].

Machine Learning Approaches in Biomarker Discovery

Supervised Learning for Predictive Biomarker Identification

Supervised machine learning approaches train models on labeled datasets to classify disease status or predict clinical outcomes based on input features [10] [8]. These methods have demonstrated particular utility in biomarker discovery, where they can integrate diverse data types to identify patterns associated with specific phenotypes. Common supervised algorithms include support vector machines (SVMs), which identify optimal hyperplanes for separating classes in high-dimensional spaces; random forests, ensemble methods that aggregate multiple decision trees for robust classification; and gradient boosting algorithms (XGBoost, LightGBM) that iteratively correct previous prediction errors [8] [11]. These approaches have successfully identified diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers across oncology, infectious diseases, neurological disorders, and autoimmune conditions [8].

Unsupervised Learning for Novel Disease Endotyping

Unsupervised learning methods explore unlabeled datasets to discover inherent structures or novel subgroupings without predefined outcomes [7] [8]. These approaches are invaluable for endotyping—classifying diseases based on underlying biological mechanisms rather than purely clinical symptoms [7]. Techniques include clustering methods (k-means, hierarchical clustering) that group patients with similar molecular profiles, and dimensionality reduction approaches (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP) that project high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional spaces for visualization and pattern recognition [7]. The concept of disease endotyping was first defined in asthma, where transcriptomics revealed immune/inflammatory endotypes with direct implications for targeted treatment strategies [7]. Unsupervised learning often serves as the initial step in bioinformatics pipelines, enabling quality control, outlier detection, and hypothesis generation before applying supervised approaches [7].

Experimental Protocol: ML-Driven Biomarker Discovery for Large-Artery Atherosclerosis

Study Design and Sample Preparation

This protocol outlines a machine learning workflow for biomarker discovery in large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA), adapted from a published study [11]. The study employs a case-control design with ischemic stroke patients exhibiting extracranial LAA (≥50% diameter stenosis) and normal controls (<50% stenosis confirmed by angiography). Participants are excluded for systemic diseases, cancer, or acute illness at recruitment. Blood samples are collected in sodium citrate tubes and processed within one hour of collection (centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C). Plasma aliquots are stored at -80°C until metabolomic analysis. The targeted metabolomics approach uses the Absolute IDQ p180 kit (Biocrates Life Sciences) to quantify 194 endogenous metabolites across multiple compound classes, with analysis performed on a Waters Acquity Xevo TQ-S instrument [11].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolomic Biomarker Discovery

| Research Reagent | Manufacturer/Catalog | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute IDQ p180 kit | Biocrates Life Sciences | Targeted quantification of 194 metabolites from multiple compound classes |

| Sodium citrate blood collection tubes | Various suppliers | Preservation of blood samples for plasma metabolomics |

| Waters Acquity Xevo TQ-S | Waters Corporation | Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry system for metabolite quantification |

| Biocrates MetIDQ software | Biocrates Life Sciences | Data processing and metabolite level determination |

| Pandas Python package | Python Software Foundation | Data preprocessing, manipulation, and analysis |

| scikit-learn Python package | Python Software Foundation | Machine learning algorithms and model implementation |

Data Preprocessing and Machine Learning Workflow

The analytical workflow begins with data preprocessing, including missing data imputation (mean imputation), label encoding for categorical variables, and dataset splitting (80% for training/validation, 20% for external testing) [11]. Three feature sets are evaluated: clinical factors alone, metabolites alone, and combined clinical factors with metabolites. Six machine learning models are implemented and compared: logistic regression (LR), support vector machines (SVM), decision trees, random forests (RF), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), and gradient boosting [11]. Feature selection employs recursive feature elimination with cross-validation to identify the most predictive biomarkers. Models are trained with tenfold cross-validation on the training set, with hyperparameter optimization, before final evaluation on the held-out test set. Performance metrics include area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity [11].

Results and Biomarker Interpretation

In the referenced LAA study, the logistic regression model achieved the best prediction performance with an AUC of 0.92 when incorporating 62 features in the external validation set [11]. The model identified LAA as being predicted by clinical risk factors (body mass index, smoking, medications for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia) and metabolites involved in aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis and lipid metabolism [11]. Importantly, 27 features were consistently selected across five different models, and when used in the logistic regression model alone, achieved an AUC of 0.93, suggesting their robustness as candidate biomarkers [11]. This demonstrates the effectiveness of combining multiple machine learning algorithms with rigorous feature selection for identifying reproducible biomarker signatures with strong predictive power for complex diseases.

Advanced Applications: AI-Assisted Sensor Systems and Multi-Omics Integration

AI-Enhanced Wearable Sensors for Biomarker Monitoring

Emerging technologies combine wearable biosensors with machine learning for continuous biomarker monitoring. Recent research demonstrates an artificial intelligence-assisted wearable microfluidic colorimetric sensor system (AI-WMCS) for rapid, non-invasive detection of key biomarkers in human tears, including vitamin C, H+ (pH), Ca2+, and proteins [12]. The system comprises a flexible microfluidic patch that collects tears and facilitates colorimetric reactions, coupled with a deep learning neural network-based cloud server data analysis system embedded in a smartphone [12]. A multichannel convolutional recurrent neural network (CNN-GRU) corrects errors caused by varying pH and color temperature, achieving determination coefficients (R²) as high as 0.998 for predicting pH and 0.994 for other biomarkers [12]. This integration of physical sensing technology with machine learning enables accurate, simultaneous detection of multiple biomarkers using minimal sample volume (~20 μL), demonstrating the potential for continuous health monitoring.

Multi-Omics Integration for Comprehensive Biological Insight

Machine learning enables the integration of diverse data types, moving beyond single-omics approaches to multi-omics integration [8]. This comprehensive approach combines genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, imaging data, and clinical records to provide holistic molecular profiles [8] [9]. Deep learning architectures, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), are well-suited for these complex biomedical data integration tasks [8]. CNNs excel at identifying spatial patterns in imaging data such as histopathology, while RNNs capture temporal dependencies in longitudinal biomarker measurements [8]. The integration of multi-omics data has been shown to improve early Alzheimer's disease diagnosis specificity by 32%, providing a crucial intervention window [9]. This approach facilitates the identification of intricate patterns and interactions among various molecular features that were previously unrecognized using conventional analytical methods.

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Critical Implementation Considerations

Despite their promise, machine learning approaches face several challenges in biomarker discovery. Model interpretability remains a significant hurdle, as many advanced algorithms function as "black boxes," making it difficult to elucidate the biological rationale behind specific predictions [8]. This lack of transparency poses practical barriers to clinical adoption, where trust in predictive models is essential [8]. Additionally, rigorous external validation using independent cohorts is necessary to ensure reproducibility and clinical reliability [8]. Data quality issues, including limited sample sizes, noise, batch effects, and biological heterogeneity, can severely impact model performance, leading to overfitting and reduced generalizability [8]. Ethical and regulatory considerations also influence deployment, as biomarkers used for patient stratification or therapeutic decisions must comply with rigorous FDA standards [8].

Emerging Solutions and Methodological Advances

Several emerging approaches address these implementation challenges. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques provide explanations for predictions that can be explored mechanistically before proceeding to validation studies [7]. The rise of explainable AI improves opportunities for true discovery by enhancing model interpretability [7]. Transfer learning approaches leverage knowledge from related domains to improve performance with limited data, while semi-supervised learning effectively utilizes both labeled and unlabeled data [10]. For regulatory compliance, researchers are developing frameworks that maintain model performance while ensuring transparency and fairness [9]. Future directions include expanding biomarker discovery to rare diseases, incorporating dynamic health indicators, strengthening integrative multi-omics approaches, conducting longitudinal cohort studies, and leveraging edge computing solutions for low-resource settings [9]. These advances promise to enhance personalized treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes through more precise biomarker-driven medicine.

The field of biomarker discovery is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from correlation-based observations to causation-driven mechanistic insights. Biomarkers, defined as measurable indicators of biological processes, pathological states, or responses to therapeutic interventions, are critical components of precision medicine [8]. They facilitate accurate diagnosis, effective risk stratification, continuous disease monitoring, and personalized treatment decisions, particularly for complex diseases such as cancer, severe asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [8] [13] [14]. Traditional biomarker discovery approaches have predominantly focused on single molecular features, such as individual genes or proteins identified through genome-wide association studies. However, these conventional methodologies face significant challenges, including limited reproducibility, high false-positive rates, inadequate predictive accuracy, and an inherent inability to capture the multifaceted biological networks that underpin disease mechanisms [8].

The integration of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) with multi-omics technologies represents a paradigm shift in biomarker research. These advanced computational techniques can analyze large, complex biological datasets—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, imaging data, and clinical records—to identify reliable and clinically useful biomarkers [8]. This approach has enabled the emergence of endotype-based classification, which categorizes disease subtypes based on shared molecular mechanisms rather than solely clinical symptoms [14]. The distinction between phenotypes and endotypes is crucial: while phenotypes represent observable clinical characteristics, endotypes reflect the underlying biological or molecular mechanisms that give rise to these observable traits [14]. For instance, in severe asthma, the "frequent exacerbator" phenotype may result from distinct endotypes such as eosinophilic inflammation or infection-dominated mechanisms, each with different therapeutic implications [13].

This Application Note outlines standardized protocols for biomarker discovery and validation, with particular emphasis on causal machine learning approaches that bridge the gap from correlation to causation, ultimately enabling more precise patient stratification and targeted therapeutic interventions.

Biomarker Classification and Clinical Applications

Biomarkers can be broadly categorized based on their clinical applications and biological characteristics. Understanding these classifications is essential for appropriate biomarker selection, validation, and clinical implementation.

Table 1: Biomarker Types and Their Clinical Applications

| Biomarker Type | Definition | Clinical Utility | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Identifies disease presence or subtype | Disease detection and classification | MicroRNA patterns in colorectal cancer [15] |

| Prognostic | Forecasts disease progression or recurrence | Patient risk stratification | T cell exhaustion markers in cancer immunotherapy [16] |

| Predictive | Estimates treatment efficacy | Therapy selection | PD-L1 expression for immune checkpoint inhibitor response [17] |

| Pharmacodynamic | Measures biological response to treatment | Treatment monitoring and dose optimization | Blood eosinophil counts in COPD for inhaled corticosteroid guidance [14] |

| Functional | Reflects underlying biological mechanisms | Endotype identification and targeted therapy | Biosynthetic gene clusters for antibiotic discovery [8] |

The clinical implementation of biomarkers spans diverse therapeutic areas. In oncology, biomarkers guide immunotherapy approaches, with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis having revolutionized non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treatment [17]. Similarly, in respiratory medicine, biomarkers such as blood eosinophil counts and serum C-reactive protein are progressively being implemented for patient stratification and guidance of targeted therapies for conditions like severe asthma and COPD [13] [14]. The emerging framework of "treatable traits" enhances personalized management by addressing modifiable factors beyond conventional diagnostic boundaries, including comorbidities, psychosocial determinants, and exacerbation triggers [14].

The Correlation Problem in Traditional Biomarker Discovery

Conventional biomarker discovery approaches predominantly rely on correlation-based analyses, which present significant limitations for clinical translation. A systematic review of 90 studies on immune checkpoint inhibitors revealed that despite employing ML or deep learning techniques, none incorporated causal inference [18]. This fundamental methodological flaw has profound implications for the reliability and clinical applicability of identified biomarkers.

Key Limitations of Correlation-Based Approaches

- Confounding Factors: Traditional models often fail to account for key confounding variables. In studies on the gut microbiome and immune checkpoint inhibitors, only 4 out of 27 studies conducted cross-validation, and crucial confounders such as antibiotic use and dietary differences were inadequately controlled [18].

- Immortal Time Bias: Correlation-based analyses can produce dramatically misleading results. For instance, in studying immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and survival, traditional Cox regression yielded a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.37, suggesting a protective effect of irAEs. However, causal ML using target trial emulation revealed a true HR of 1.02—completely overturning the conventional belief [18].

- Spurious Radiomic Associations: Deep learning models based on CT radiomics for predicting ICI responses reported an AUC of ~0.71, but the captured signals largely reflected confounders such as tumor burden and treatment line rather than true drug sensitivity [18].

Statistical Concerns in Biomarker Validation

Biomarker validation must discern associations that occur by chance from those reflecting true biological relationships. Several statistical issues commonly undermine validation studies:

- Within-Subject Correlation: When multiple observations are collected from the same subject, correlated results can inflate type I error rates and produce spurious findings. For example, in a study of microRNA expression in colorectal cancer, 36 miRNAs appeared significantly differentially expressed in unadjusted analyses, but none remained significant after adjustment for within-patient correlation [15].

- Multiplicity: The probability of false discovery increases with each additional test conducted. Biomarker validation studies are particularly sensitive to false positives because the list of potential markers is characteristically extensive [15].

- Selection Bias: Retrospective biomarker studies often suffer from selection bias inherent to observational studies, potentially skewing results and limiting generalizability [15].

Causal Machine Learning: From Correlation to Causation

Causal machine learning represents a paradigm shift in biomarker discovery, integrating causal inference with predictive modeling to distinguish genuine causal relationships from spurious correlations.

Advanced Causal ML Methodologies

Table 2: Causal Machine Learning Approaches for Biomarker Discovery

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted-BEHRT | Combines transformer architecture with doubly robust estimation | Infers long-term treatment effects from longitudinal data | Temporal treatment response modeling [18] |

| CIMLA | Causal inference using Markov logic networks | Exceptional robustness to confounding in gene regulatory networks | Tumor immune regulation analysis [18] |

| CURE | Leverages large-scale pretraining for treatment effect estimation | ~4% AUC and ~7% precision-recall improvement over traditional methods | Immunotherapy response prediction [18] |

| Causal-stonet | Handles multimodal and incomplete datasets | Effective for big-data immunology research with missing data | Multi-omics integration [18] |

| LiNGAM-based Models | Linear non-Gaussian acyclic model for causal discovery | Directly identifies causative factors (84.84% accuracy with logistic regression) | Mechanistic biomarker identification [18] |

Experimental Protocol: Causal Biomarker Validation Pipeline

Protocol 1: Integrated Workflow for Causal Biomarker Discovery and Validation

Objective: To establish a standardized pipeline for identifying and validating causal biomarkers using multi-omics data and causal machine learning approaches.

Materials:

- Multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics)

- Clinical data and electronic health records

- High-performance computing infrastructure

- Causal ML software packages (CausalML, DoWhy, EconML)

Procedure:

Study Design and Causal Diagram Specification

- Define precise scientific objectives and scope

- Establish explicit subject inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Specify causal diagrams (Directed Acyclic Graphs) mapping hypothesized relationships between biomarkers, clinical variables, and outcomes

- Identify potential confounders, mediators, and colliders

Data Quality Control and Preprocessing

- Apply data type-specific quality metrics (fastQC for NGS data, arrayQualityMetrics for microarray data, pseudoQC for proteomics data) [19]

- Implement variance-stabilizing transformations for omics data

- Address batch effects using ComBat or similar methods

- Handle missing data through appropriate imputation techniques

Causal Feature Selection

- Apply doubly robust feature selection methods

- Implement causal forest algorithms for heterogeneous treatment effect estimation

- Use propensity score matching for observational data balancing

- Conduct sensitivity analyses for unmeasured confounding

Model Training and Validation

- Partition data into discovery (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) sets

- Train multiple causal models (Targeted-BEHRT, CIMLA, CURE)

- Implement cross-validation with strict separation between training and validation sets

- Assess model performance using AUC, precision-recall, and causal effect sizes

Biological Validation and Mechanism Elucidation

- Perform experimental validation using perturbation studies (CRISPR, siRNA)

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis for identified biomarker sets

- Validate in independent cohorts with diverse demographic characteristics

- Assess clinical utility through decision curve analysis

Expected Outcomes: Identification of causally-validated biomarkers with established biological mechanisms and demonstrated clinical utility for patient stratification and treatment selection.

Visualization of Key Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate critical workflows and signaling pathways in causal biomarker discovery, generated using Graphviz DOT language with adherence to the specified color and formatting guidelines.

Diagram 1: Causal Biomarker Discovery Workflow. This diagram outlines the comprehensive pipeline from data collection through clinical implementation of causally-validated biomarkers.

Diagram 2: T-cell Signaling and Checkpoint Inhibition. This diagram illustrates the mechanistic pathway of T-cell exhaustion and immune checkpoint inhibitor function, relevant for predictive biomarkers in cancer immunotherapy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of causal biomarker discovery requires carefully selected research tools and platforms that enable robust data generation and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Causal Biomarker Discovery

| Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-omics Platforms | RNA-seq, LC-MS/MS, NMR spectroscopy | Comprehensive molecular profiling | Platform compatibility, batch effect control [8] [19] |

| Single-cell Technologies | 10X Genomics, CITE-seq, ATAC-seq | Cellular heterogeneity resolution | Sample processing standardization, cell viability [19] |

| Causal ML Software | CausalML, DoWhy, EconML | Causal inference implementation | Algorithmic transparency, validation requirements [18] |

| Data Quality Control | fastQC, arrayQualityMetrics, pseudoQC | Data quality assessment and assurance | Platform-specific metrics, outlier detection [19] |

| Experimental Validation | CRISPR-Cas9, siRNA, organoid models | Functional validation of causal relationships | Physiological relevance, scalability [8] [18] |

| 19-Oxocinobufagin | 19-Oxocinobufagin, MF:C26H32O7, MW:456.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Secologanic acid | Secologanic acid, MF:C16H22O10, MW:374.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Standardized Protocols for Biomarker Validation

Protocol for Multi-omics Data Integration

Objective: To integrate diverse omics datasets for comprehensive biomarker discovery while accounting for technical and biological variability.

Procedure:

Data Normalization

- Apply variance-stabilizing transformation to RNA-seq data

- Perform quantile normalization for proteomics data

- Use probabilistic quotient normalization for metabolomics data

Multi-omics Integration

- Implement early integration using sparse canonical correlation analysis

- Apply intermediate integration via multimodal neural networks

- Conduct late integration through stacked generalization

Causal Network Construction

- Build causal networks using LiNGAM-based approaches

- Validate edge directions through perturbation data

- Annotate networks with functional genomic information

Quality Control Metrics: Assess integration success through cross-omics consistency checks and biological coherence evaluation.

Protocol for Clinical Biomarker Validation

Objective: To validate putative biomarkers in independent clinical cohorts using causal inference approaches.

Procedure:

Cohort Selection

- Define inclusion/exclusion criteria a priori

- Match cases and controls for potential confounders

- Ensure adequate sample size through power calculations

Measurement Standardization

- Establish standard operating procedures for biomarker quantification

- Implement blinding procedures to prevent measurement bias

- Include quality control samples in each batch

Causal Effect Estimation

- Apply propensity score methods for treatment effect estimation

- Use instrumental variable analysis when appropriate

- Conduct sensitivity analyses for unmeasured confounding

Clinical Utility Assessment

- Evaluate reclassification metrics (NRI, IDI)

- Perform decision curve analysis

- Assess cost-effectiveness where applicable

The transition from correlation to causation represents a fundamental evolution in biomarker discovery. By integrating causal machine learning with multi-omics technologies and rigorous validation frameworks, researchers can identify biomarkers with genuine biological mechanisms and enhanced clinical utility. The implementation of standardized protocols, such as those outlined in this Application Note, will accelerate the discovery of causal biomarkers and their translation into clinical practice.

Future directions in causal biomarker discovery include the development of perturbation cell atlases, federated causal learning frameworks that preserve data privacy, and dynamic biomarker monitoring systems that adapt to disease progression and treatment responses. These advancements, coupled with ongoing improvements in causal inference methodologies, promise to transform precision medicine by enabling truly mechanistic patient stratification and targeted therapeutic interventions.

As the field progresses, emphasis must remain on rigorous validation, biological plausibility, and clinical relevance to ensure that causal biomarkers fulfill their promise of improving patient outcomes across diverse disease contexts.

The advent of large-scale public genomic data repositories has revolutionized the field of biomedical research, providing an unprecedented resource for machine learning (ML)-driven biomarker discovery. For researchers focused on protein and immunology (POI) biomarkers, resources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE), and the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) offer complementary data types that can be integrated to uncover novel diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic targets. These repositories provide systematically generated, multi-omics data at a scale that enables the training of robust ML models capable of identifying subtle patterns indicative of disease states, treatment responses, and biological mechanisms. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for effectively leveraging these resources within the context of ML-powered POI biomarker research, facilitating their use by scientists and drug development professionals.

A strategic understanding of the scope, content, and strengths of each repository is fundamental to designing effective biomarker discovery pipelines. The following table summarizes the core characteristics and quantitative data available from each resource.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Public Genomic Data Repositories

| Repository | Primary Focus | Key Data Types | Data Volume (as of 2024/2025) | Primary Applications in Biomarker Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA [20] [21] | Cancer Genomics | RNA-seq, WGS, WES, DNA methylation, CNVs, clinical data | >20,000 cases across 33 cancer types; Multi-modal data per patient | Pan-cancer biomarker identification, prognostic model development, cancer subtype classification |

| ENCODE [22] [23] | Functional Genomics | ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, RNA-seq, Hi-C, CRISPR screens | ~106,000 released datasets; >23,000 functional genomics experiments [22] | Defining regulatory elements, understanding gene regulation mechanisms, prioritizing non-coding variants |

| gnomAD [24] [25] | Population Genetics & Variation | Allele frequencies, constraint metrics, variant co-occurrence, haplotype data | v4: 807,162 individuals; v3.1: 76,156 whole genomes [24] [25] | Filtering benign variants, assessing population-specific allele frequency, estimating genetic prevalence |

Experimental Protocols and Data Access

Protocol 1: Downloading and Preprocessing Multi-omics Data from TCGA

This protocol outlines a streamlined pipeline for downloading TCGA data and reorganizing it for patient-level, multi-omics analysis, which is crucial for building integrated ML models for biomarker discovery.

I. Prerequisites and Setup

- Software Installation: Create a Conda environment with the required packages (Python 3.11.8, Snakemake 7.32.4, pandas, gdc-client) using the provided

TCGADownloadHelper_env.yamlfile [20]. - Folder Structure: Establish a local analysis directory with subfolders:

sample_sheets/manifests,sample_sheets/sample_sheets_prior, andsample_sheets/clinical_data[20].

II. Data Selection and Download

- Access the GDC Data Portal: Navigate to the GDC Data Portal.

- Build a Cart: Use the faceted search to select files of interest (e.g., RNA-seq counts, WES VCFs, clinical data) for a specific cohort (e.g., TCGA-LUAD, TCGA-COAD) [20].

- Export Metadata: Download the

manifest fileandsample sheetfrom the cart, saving them in themanifestsandsample_sheets_priorfolders, respectively. Export the clinical metadata to theclinical_datafolder. - Download Raw Data: Use the GDC Data Transfer Tool with the manifest file to download the selected files. For restricted data, use an NIH access token [20].

III. Data Reorganization and Preprocessing

- Execute Renaming Pipeline: Run the

TCGADownloadHelperSnakemake pipeline or Jupyter Notebook to map the opaque GDC file names to human-readable Case IDs using the sample sheet [20]. - Integrate Clinical Data: Merge the reorganized molecular data files with the clinical metadata using the Case ID as the key.

- Data Formatting for ML: Convert the processed data into a matrix format (e.g., features × samples) suitable for ML input. Perform standard preprocessing steps such as log-transformation for RNA-seq counts, imputation of missing values, and normalization.

Protocol 2: Interrogating Functional Elements with ENCODE Data

This protocol describes how to access and utilize ENCODE data to inform on the potential functional impact of genomic regions identified in biomarker studies.

I. Portal Navigation and Data Selection

- Access the ENCODE Portal: Navigate to https://www.encodeproject.org [22] [23].

- Faceted Search: Use the search interface with predefined facets (e.g.,

Assay type,Biosample,Target of assay) to find relevant datasets. For POI research, key assays include Histone ChIP-seq (H3K27ac for enhancers), ATAC-seq (accessibility), and RNA-seq [22]. - Review Uniform Processing Pipelines: Prioritize datasets that have been processed through ENCODE's uniform pipelines to ensure consistency and quality [22]. Check the File Association Graph on experiment pages for quality metrics [22].

II. Data Access and Visualization

- File Download: Add selected files to the cart. Use the cart's enhanced interface to filter by file properties (e.g.,

file type=bigWigfor coverage tracks) and download via the browser or programmatically using the REST API [22] [23]. - Genome Browser Visualization: Visualize

bigWigorBEDfiles directly in the integrated Valis Genome Browser or the Encyclopaedia Browser to see annotations in a genomic context [22].

III. Integration with Biomarker Lists

- Overlap Analysis: Cross-reference a list of genomic coordinates from your biomarker study (e.g., non-coding variants, differentially accessible regions) with ENCODE annotations to predict functional relevance (e.g., whether a variant falls in an active enhancer in a relevant cell type).

Protocol 3: Annotating and Filtering Variants with gnomAD

This protocol is essential for assessing the population frequency and constraint of genetic variants, a critical step in prioritizing pathogenic biomarkers.

I. Browser-Based Variant Interrogation

- Access the gnomAD Browser: Navigate to https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org.

- Gene-Centric Query: Enter a gene symbol (e.g.,

APOL1) to view a constraint metric summary (pLoF and missense Z-scores) and a table of all variants within the gene [24]. - Variant-Specific Query: Search for a specific variant (e.g.,

17-7043011-C-T) to view its allele frequency across global populations and sub-populations [25]. - Utilize Advanced Features:

- Local Ancestry Inference (LAI): For admixed populations (African/African American, Admixed American), check the "Local Ancestry" tab on the variant page to view ancestry-specific frequencies (LAI-AFR, LAI-EUR, LAI-AMR), which can reveal masked high-frequency alleles [25].

- Variant Co-occurrence: On gene pages for v2 data, check the variant co-occurrence table to see if pairs of rare variants are observed in trans, which can aid in interpreting recessive conditions [24].

II. Programmatic Data Access for ML

- Download Bulk Data: Access the complete VCF files or Hail Tables for gnomAD data from the downloads page [26].

- Annotate Variant Lists: Integrate gnomAD allele frequencies and constraint metrics into your variant annotation pipeline using tools like

bcftoolsor Hail. Filter out common variants (e.g., AF > 0.1%) in any population as likely benign.

Integration for Machine Learning Biomarker Discovery

The power of these repositories is magnified when their data is integrated into a unified ML workflow for POI biomarker discovery.

Workflow Diagram: Integrated ML Pipeline for Biomarker Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of data from the repositories into a cohesive machine learning pipeline.

Application Note: A Case Study in Colon Adenocarcinoma

Recent research exemplifies the power of integrating TCGA data with ML for biomarker discovery. A 2025 study identified a taurine metabolism-related gene signature for prognostic stratification in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) using TCGA data [27]. The workflow involved:

- Data Sourcing: RNA-seq and clinical data for the TCGA-COAD cohort were sourced from the GDC portal [27].

- Unsupervised Clustering: Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) was applied to genes with prognostic significance, identifying two distinct molecular subtypes (C1 and C2) associated with taurine metabolism [27].

- Differential Analysis & Functional Enrichment: Analysis of 199 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between clusters revealed enrichment in extracellular matrix organization and immune activity, suggesting distinct tumor microenvironments [27].

- Predictive Model Building: Using LASSO and multivariate Cox regression, a prognostic model based on nine key genes (

LEP,SERPINA1,ENO2,HSPA1A,GSR,GABRD,TERT,NOTCH3, andMYB) was constructed. The model demonstrated predictive efficacy with AUCs of 0.698, 0.699, and 0.73 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival, respectively [27].

This end-to-end analysis demonstrates a reproducible blueprint for using TCGA to derive a clinically actionable biomarker signature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for executing the protocols described in this article.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Data Analysis

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGADownloadHelper [20] | Pipeline (Snakemake/Jupyter) | Simplifies TCGA data download and file renaming | Protocol 1: Automates the mapping of GDC file IDs to human-readable Case IDs, crucial for multi-modal data integration. |

| GDC Data Transfer Tool [20] | Command-line Tool | Bulk download of data from the GDC Portal | Protocol 1: Enables efficient, reliable download of large TCGA datasets specified by a manifest file. |

| ENCODE REST API [23] | Application Programming Interface | Programmatic access to ENCODE metadata and files | Protocol 2: Allows for automated, scripted querying and retrieval of ENCODE data, facilitating reproducible analysis. |

| Valis/Encyclopaedia Browser [22] | Genome Browser | Visualization of genomic data tracks | Protocol 2: Provides an intuitive visual context for ENCODE functional genomics data within the genome. |

| gnomAD Browser [24] | Web Application | Interactive exploration of gnomAD data | Protocol 3: Enables rapid, user-friendly lookup of variant frequencies, constraint scores, and local ancestry data. |

| Hail [26] | Library/Framework (for Python) | Scalable genomic data analysis | Protocol 3: Used for large-scale handling and analysis of gnomAD VCFs or Hail Tables for population-scale analysis. |

| 23-Hydroxylongispinogenin | 23-Hydroxylongispinogenin, CAS:42483-24-9, MF:C30H50O4, MW:474.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Astragaloside VI | Astragaloside VI, MF:C47H78O19, MW:947.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The strategic integration of TCGA, ENCODE, and gnomAD provides a formidable foundation for machine learning-driven biomarker discovery. TCGA offers the disease-specific, multi-omics, and clinical context; ENCODE provides the functional genomic annotation to interpret findings mechanistically; and gnomAD delivers the population genetics framework to prioritize rare, potentially pathogenic variants. By following the detailed protocols and workflows outlined in this article, researchers can systematically navigate these complex resources, extract biologically and clinically relevant signals, and build robust models to identify the next generation of protein and immunology biomarkers. The continuous updates and increasing scale of these repositories promise to further enhance their utility in the years to come.

The ML Toolbox: Practical Algorithms and Real-World Applications in Biomarker Development

The discovery of robust and reproducible biomarkers has been revolutionized by sensitive omics platforms that enable measurement of biological molecules at an unprecedented scale [7]. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a critical tool for analyzing these complex datasets, moving beyond traditional statistical methods that struggle with the scale, multiple testing, and non-linear relationships inherent in high-dimensional biological data [7]. Biomarkers—measurable indicators of biological processes, pathological states, or responses to therapeutic interventions—are crucial for disease diagnosis, prognosis, personalized treatment decisions, and monitoring treatment efficacy in precision medicine [8] [28]. The choice between supervised and unsupervised learning approaches represents a fundamental decision point in biomarker discovery pipelines, with significant implications for study design, analytical methodology, and clinical applicability.

Core Concepts: Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning

Fundamental Differences and Applications

The primary distinction between supervised and unsupervised learning lies in the use of labeled datasets [29]. Supervised learning uses labeled input and output data to train algorithms for classifying data or predicting outcomes, while unsupervised learning algorithms analyze and cluster unlabeled data sets without human intervention to discover hidden patterns [29].

| Characteristic | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Labeled datasets with known outcomes [29] | Unlabeled datasets without predefined outcomes [29] |

| Primary Goals | Predict outcomes for new data; classification and regression [29] | Discover inherent structures; clustering, association, dimensionality reduction [29] |

| Common Algorithms | Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines, Random Forest, XGBoost [8] [11] | K-means clustering, Principal Component Analysis, hierarchical clustering [8] [30] |

| Model Complexity | Relatively simple; calculated using programs like R or Python [29] | Computationally complex; requires powerful tools for large unclassified data [29] |

| Key Applications in Biomarker Research | Disease classification, outcome prediction, treatment response [11] | Patient stratification, disease subtyping, novel biomarker identification [31] [30] |

| Output Validation | Direct accuracy measurement against known labels [29] | Requires human intervention to validate output variables [29] |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The methodological pipeline for biomarker discovery differs significantly between supervised and unsupervised approaches, impacting everything from initial study design to final validation.

Supervised Learning Approaches in Biomarker Discovery

Methodological Framework and Protocols

Supervised learning involves training a model on a labeled dataset where both input data (e.g., gene expression or proteomic measurements) and output data (e.g., disease diagnosis or prognosis) are known [7]. The goal is to learn a mapping from inputs to outputs so the model can make predictions on new, unseen data [7]. This approach is particularly valuable when researchers have well-defined clinical outcomes or diagnostic categories.

Experimental Protocol: Supervised Biomarker Signature Development

Study Design and Cohort Selection

- Precisely define primary and secondary biomedical outcomes

- Establish clear subject inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Perform sample size determination and power analysis

- Implement sample selection and matching methods for confounder matching between cases and controls [19]

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Collect multimodal data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, clinical variables)

- Apply data type-specific quality control metrics (e.g., fastQC for NGS data, arrayQualityMetrics for microarray data) [19]

- Handle missing values (removal or imputation for features with <30% missing values)

- Remove features with zero or small variance

- Apply appropriate transformations (e.g., Box-Cox, variance stabilizing transformations) [19]

Feature Selection and Model Training

- Apply feature selection methods (LASSO, recursive feature elimination) to identify informative biomarkers [11]

- Split data into training/validation (80%) and testing (20%) sets [11]

- Implement multiple algorithms (Logistic Regression, SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost) with cross-validation [11]

- Tune hyperparameters using grid search or Bayesian optimization

Model Validation and Biomarker Confirmation

Case Study: Predicting Large-Artery Atherosclerosis

A study on large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA) demonstrated the effective application of supervised learning for biomarker discovery [11]. Researchers integrated clinical factors and metabolite profiles using six machine learning models, with logistic regression exhibiting the best prediction performance (AUC=0.92 in external validation) [11]. The study identified that combining clinical risk factors (body mass index, smoking, medications for diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia) with metabolites involved in aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis and lipid metabolism provided the most stable predictive model [11]. Notably, 27 features were present across five different models, and using only these shared features in the logistic regression model achieved an AUC of 0.93, highlighting their importance as candidate biomarkers [11].

Unsupervised Learning Approaches in Biomarker Discovery

Methodological Framework and Protocols

Unsupervised learning involves training a model on an unlabeled dataset to uncover patterns or relationships without any prior knowledge or assumptions about the output [7]. This approach is particularly valuable for exploring complex, multimodal datasets without predefined categories or for identifying novel disease subtypes.

Experimental Protocol: Unsupervised Biomarker Discovery

Data Collection and Multimodal Integration

- Collect diverse data modalities (metabolome, microbiome, genetics, advanced imaging, clinical data) [31]

- Perform data transformation to address non-Gaussian distributions (e.g., rank-based inverse normal transformation) [31]

- Correct for covariates (age, sex, ancestry) using multiple linear regression [31]

Cross-Modality Association Network Construction

Module Identification and Biomarker Extraction

Patient Stratification and Clinical Validation

Case Study: Novel Signatures from Multimodal Data

A comprehensive study analyzing 1385 data features from 1253 individuals demonstrated the power of unsupervised learning for identifying novel biomarker signatures [31]. Researchers utilized a combination of unsupervised machine learning methods including cross-modality associations, network analysis, and patient stratification. The approach identified cardiometabolic biomarkers beyond standard clinical measures, with stratification based on these signatures identifying distinct subsets of individuals with similar health statuses [31]. Notably, subset membership was a better predictor for diabetes than established clinical biomarkers such as glucose, insulin resistance, and body mass index [31]. Specific novel biomarkers identified included 1-stearoyl-2-dihomo-linolenoyl-GPC and 1-(1-enyl-palmitoyl)-2-oleoyl-GPC for diabetes, and cinnamoylglycine as a potential biomarker for both gut microbiome health and lean mass percentage [31].

Integrated and Advanced Approaches

Hybrid Methodologies and Causal Inference

Advanced biomarker discovery increasingly integrates both supervised and unsupervised approaches with causal inference methods to enhance biomarker validation and biological interpretation.

Addressing Bias and Enhancing Generalizability

An important consideration in biomarker discovery is addressing potential biases in machine learning algorithms. Recent research has highlighted sex-based bias in ML models, showing that stratifying data according to sex improves prediction accuracy for clinical biomarkers including triglycerides, BMI, waist circumference, and systolic blood pressure [28]. For predictions within 10% error, the top performing models for waist circumference, albuminuria, BMI, blood glucose and systolic blood pressure showed males scoring higher than females, highlighting the importance of considering biological sex in biomarker discovery pipelines [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Biomarker Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Omics Profiling Platforms | Absolute IDQ p180 kit (Biocrates) [11] | Targeted metabolomics analysis quantifying 194 endogenous metabolites from 5 compound classes |

| Biobanking Supplies | Sodium citrate tubes, polypropylene tubes [11] | Standardized blood collection and plasma storage at -80°C for reproducible metabolomic measurements |

| Quality Control Software | fastQC/FQC [19], arrayQualityMetrics [19], pseudoQC, MeTaQuaC, Normalyzer [19] | Data type-specific quality metrics for NGS, microarray, proteomics, and metabolomics data |

| Data Processing Tools | Pandas, NumPy, scikit-learn [11] | Python-based data preprocessing, feature selection, and machine learning implementation |

| Visualization Packages | Matplotlib, Seaborn [11] | Creation of publication-quality figures including PCA plots, t-SNE visualizations, and correlation matrices |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | SciPy, TableOne [11] | Statistical testing and cohort characterization for clinical and biomarker data |

| Network Analysis Software | Graphical Lasso implementation [31] | Construction of sparse Markov networks for identifying key biomarkers within functional modules |

| Validation Resources | Independent longitudinal cohorts [31] | Confirmation of biomarker stability and predictive performance over time |

| 1,1,1,1-Kestohexaose | 1,1,1,1-Kestohexaose, MF:C36H62O31, MW:990.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Chrysogine | 2-(1-Hydroxyethyl)-4(3H)-quinazolinone | High-purity 2-(1-Hydroxyethyl)-4(3H)-quinazolinone for research. Explore its applications in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The choice between supervised and unsupervised learning in biomarker discovery depends on multiple factors including research objectives, data characteristics, and available clinical annotations. Supervised learning approaches are ideal when researchers have well-defined clinical endpoints or diagnostic categories and aim to develop predictive models for classification or outcome prediction [29] [11]. In contrast, unsupervised methods are particularly valuable for exploratory analysis of complex multimodal datasets, identification of novel disease subtypes or endotypes, and discovery of previously unrecognized biomarker patterns [31] [30].

Emerging trends in the field include the integration of both approaches in hybrid pipelines, where unsupervised learning identifies novel patient subgroups or biomarker patterns that subsequently inform supervised model development [32]. Additionally, the incorporation of causal inference methods like Mendelian randomization strengthens the biological validation of discovered biomarkers [32]. As multimodal data collection becomes increasingly comprehensive and complex, the strategic selection and integration of machine learning approaches will continue to drive advances in biomarker discovery, ultimately enhancing personalized medicine through improved diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection.

Application Notes

In the field of machine learning-driven biomarker discovery, the selection of an appropriate algorithm is critical for identifying robust, biologically relevant signatures from high-dimensional data. This document outlines the practical application, performance, and protocols for four core algorithms: Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Support Vector Machine (SVM). These algorithms facilitate the transition from vast omics datasets to a concise set of potential biomarkers for diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive purposes.

The comparative performance of these algorithms, as evidenced by recent research, is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Core Algorithms in Biomarker Discovery

| Algorithm | Reported AUC | Key Strengths | Common Feature Selection Methods | Exemplary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression (LR) | 0.92–0.93 [11] | Highly interpretable, provides odds ratios, less prone to overfitting with regularization. | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Bagged Logistic Regression (BLESS) [33] | Predicting Large-Artery Atherosclerosis (LAA) from clinical and metabolomic data [11]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | 0.809–0.91 [11] [34] | Robust to outliers and non-linear data, intrinsic variable importance ranking. | Boruta, Permutation Importance, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [34] | Classifying carotid artery plaques; stable biomarker identification framework [11] [34]. |

| XGBoost | >0.90 [35] | High accuracy, handles missing data, effective for complex interactions. | Embedded feature importance, Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithms (e.g., MEvA-X) [36] | Ovarian cancer diagnosis; precision nutrition and weight loss prediction [36] [35]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 0.98 (Accuracy) [37] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, versatile kernels for non-linear separation. | RFE (SVM-RFE), Network-constrained regularization (CNet-SVM) [37] [38] | Identifying racial disparity biomarkers in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) [37]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Biomarker Discovery Using Logistic Regression with RFE

Application: This protocol is ideal for creating interpretable models where understanding the specific contribution of each biomarker is crucial. It has been successfully used to predict Large-Artery Atherosclerosis (LAA) by integrating clinical factors and metabolite profiles [11].

- Step 1: Data Preprocessing. Handle missing values using mean imputation. Encode categorical variables (e.g., smoking status, medication use) as dummy variables. Split the dataset into training/validation (80%) and external testing (20%) sets [11].

- Step 2: Feature Selection with RFE. Use Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) on the training set. The LR model is trained, and the least important features are pruned iteratively. Cross-validation determines the optimal number of features.

- Step 3: Model Training. Train a final Logistic Regression model on the entire training set using the optimal features identified in Step 2. Use regularization (e.g., L1 or L2) to enhance model generalization.

- Step 4: Model Evaluation. Validate the model on the held-out external test set. Evaluate performance using Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), with an AUC >0.9 indicating an excellent diagnostic biomarker [39]. Calculate sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.

Protocol 2: Stable Biomarker Identification with Random Forest and Boruta

Application: This protocol is suited for discovering stable and robust biomarkers from high-dimensional omics data (transcriptomics, metabolomics) where complex, non-linear relationships are suspected. A power analysis framework can be integrated for future study design [34].

- Step 1: Nested Cross-Validation Setup. Implement a nested cross-validation to ensure unbiased performance estimation and feature selection. The outer loop is for testing (e.g., 75:25 split), and the inner loop is for hyperparameter tuning and feature selection on the training fold [34].

- Step 2: Stable Feature Selection with Boruta. Within the inner loop, run the Boruta algorithm for multiple iterations (e.g., 100). Boruta creates "shadow" features by shuffling real data and compares their importance to real features to decide significance. Features selected in >90% of iterations are considered high-stringency (HS) stable biomarkers [34].

- Step 3: Model Training and Power Analysis. Train a final Random Forest model using the stable features. The out-of-bag (OOB) error is used for internal validation. Use the identified stable features and their effect sizes to perform a power analysis for estimating sample sizes required for future validation studies [34].

Protocol 3: Advanced Biomarker Optimization with XGBoost and Evolutionary Algorithms

Application: This protocol is designed for highly complex datasets with severe class imbalance and a very low samples-to-features ratio. It is effective for finding a small set of non-redundant biomarkers while optimizing multiple, conflicting objectives (e.g., high accuracy and model simplicity) [36].

- Step 1: Data Preparation and Imbalance Handling. Prepare the dataset (e.g., gene expression, clinical questionnaires). Address class imbalance using techniques such as SMOTE or assigning higher weights to the minority class during model training.

- Step 2: Multi-Objective Evolutionary Optimization. Employ a framework like MEvA-X, which combines a multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithm (EA) with XGBoost. The EA simultaneously optimizes XGBoost's hyperparameters and performs feature selection. It evolves a population of models towards a "Pareto frontier" that balances objectives like AUC and the number of features [36].

- Step 3: Solution Selection and Validation. From the set of Pareto-optimal solutions, select one or multiple models based on the desired trade-off between performance and complexity. Validate the chosen model(s) on a hold-out test set, reporting metrics like AUC and balanced accuracy.

Protocol 4: Network-Constrained Biomarker Discovery with SVM-RFE

Application: This protocol goes beyond identifying individual biomarkers to discover functionally connected sub-networks of biomarkers. It is particularly powerful for elucidating the synergistic role of genes in complex diseases like cancer [38].

- Step 1: Integration of Prior Biological Knowledge. Collect a prior gene interaction network from databases like STRING or BioGRID. Integrate this network with the gene expression dataset.

- Step 2: Network-Constrained Feature Elimination. Implement the Connected Network-constrained SVM (CNet-SVM). The SVM optimization includes a penalty term that encourages the selection of features that are connected in the prior network. The Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) process is guided by this constraint, progressively eliminating genes that are isolated from the main connected component [38].