Optimizing SMGT Protocol for Transgenic Pig Production: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a systematic overview of the Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) protocol for generating transgenic pigs, a key technology in biomedical and agricultural research.

Optimizing SMGT Protocol for Transgenic Pig Production: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a systematic overview of the Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) protocol for generating transgenic pigs, a key technology in biomedical and agricultural research. It explores the foundational principles of SMGT, detailing its advantages over traditional methods like pronuclear microinjection. A step-by-step methodological guide is presented, from sperm preparation to embryo transfer, followed by critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance efficiency and reproducibility. The protocol is validated through comparative analysis with other genetic modification techniques and a discussion of regulatory and analytical frameworks for quality control. This guide is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to effectively apply SMGT in creating large animal models for human disease and therapeutic development.

Understanding SMGT: Principles and Advantages in Transgenic Pig Models

Defining Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) is a transgenic technique that utilizes sperm cells as natural vectors to bind, internalize, and deliver exogenous DNA into an oocyte during fertilization, resulting in the production of genetically modified animals [1] [2]. The concept was established in 1989, when it was first demonstrated that exogenous DNA incubated with mouse spermatozoa could be detected in the tissues of born offspring [2]. This discovery prompted extensive research across various species, with the dual aim of clarifying the underlying molecular mechanisms and developing biotechnological applications for generating transgenic animals [2].

SMGT has been successfully applied to produce transgenic pigs, notably for expressing human decay accelerating factor and for introducing multiple reporter genes simultaneously [3] [4]. The technique is recognized for its high efficiency, low cost, and ease of use compared to other methods like pronuclear microinjection, as it does not require embryo handling or expensive equipment [3] [4]. In the context of pig production, SMGT serves as a valuable tool for creating large animal models for medical research, agricultural applications, and xenotransplantation [3] [4].

Mechanism of SMGT

The method capitalizes on the intrinsic ability of spermatozoa to act as natural vectors for foreign genetic material. The process is not random but involves specific interactions and requires careful preparation to overcome natural biological barriers [1].

DNA Binding and Internalization

- Sperm Preparation: Seminal fluid contains an inhibitory factor that blocks the binding of exogenous DNA to sperm cells. Therefore, seminal plasma must be removed from sperm samples through extensive washing immediately after ejaculation [1].

- DNA-Protein Interaction: Exogenous DNA molecules bind to the cell membrane overlying the head of the sperm cell. This binding is mediated by specific DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) present on the sperm surface [1].

- Translocation: Once bound, the DBPs facilitate the translocation of the exogenous DNA into the sperm cell [1].

Post-Fertilization DNA Integration

After the transfected sperm cell penetrates the oocyte, the exogenous DNA must integrate into the embryonic genome. The exact mechanism is not fully defined, but several possibilities have been suggested, including:

- Integration during oocyte activation.

- Integration during sperm nucleus decondensation.

- Integration during the formation of the male and female pronuclei [1].

All proposed mechanisms agree that integration occurs after the sperm cell has entered the oocyte [1].

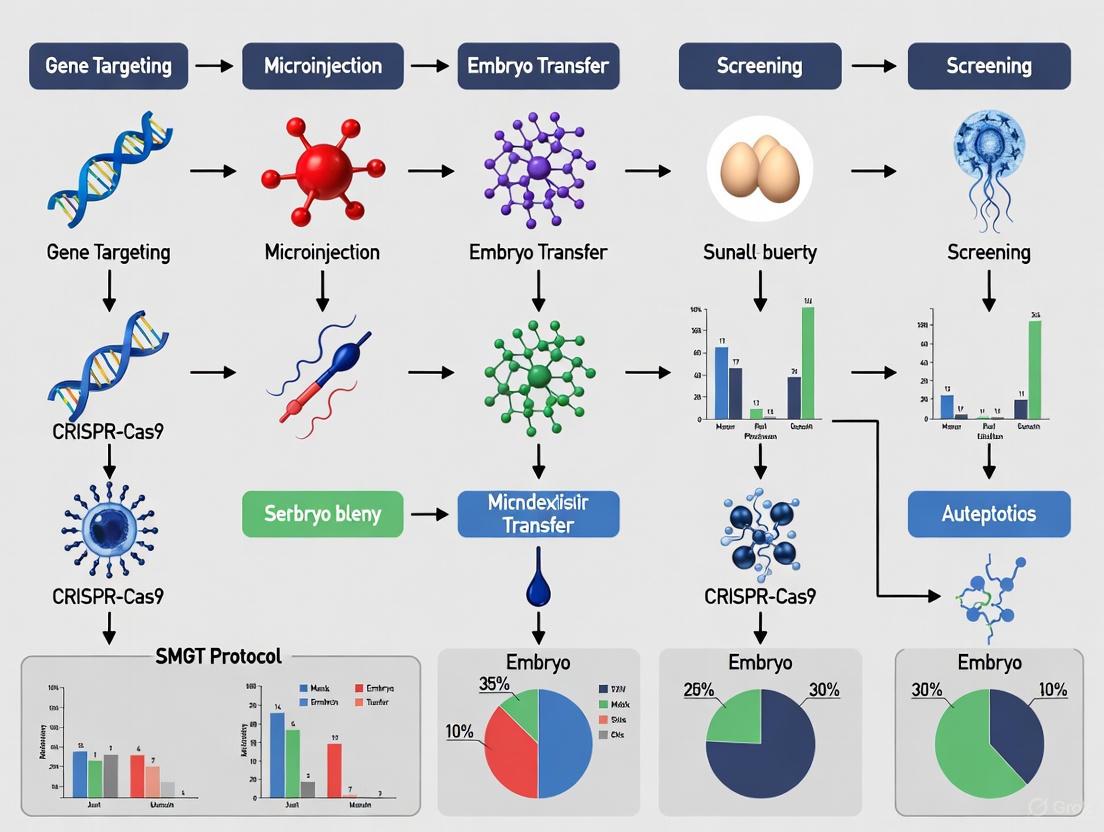

Figure 1: SMGT Workflow for Transgenic Animal Production. This diagram outlines the key steps in the SMGT protocol, from sperm preparation to the generation of a genetically modified animal.

Key Considerations and Controversies

Despite reported successes, SMGT remains a controversial technique and is not yet established as a reliable form of genetic manipulation [1]. The primary source of skepticism stems from the evolutionary implications: if sperm cells readily acted as vectors for exogenous DNA, it could lead to genetic chaos. Biological systems have therefore evolved robust barriers to minimize such occurrences [1].

The main natural barriers identified are:

- Seminal Fluid Inhibitory Factor: A factor present in mammalian seminal fluid that causes DBPs to lose their ability to bind exogenous DNA, thus blocking the first step of the process [1].

- Sperm Endogenous Nuclease Activity: An enzyme activity triggered by the interaction of sperm cells with foreign DNA molecules, likely designed to degrade the foreign genetic material [1].

The existence of these protections suggests that the successful production of transgenic animals via SMGT may represent instances where these natural barriers were overcome in the laboratory setting, which also contributes to the technique's inconsistent experimental outcomes [1].

Applications in Transgenic Pig Production

Within porcine molecular breeding, SMGT offers a straightforward method to introduce new genetic traits. The applications are particularly valuable for biomedical and agricultural research.

Table 1: SMGT Applications and Outcomes in Pig Transgenesis

| Application Area | Specific Example | Reported Outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xenotransplantation | Expression of human decay accelerating factor (hDAF) | Generation of transgenic pig lines [3] | Aims to make pig organs suitable for grafting to humans. |

| Multigene Engineering | Simultaneous introduction of three fluorescent reporter genes (eGFP, EBFB, RFP) | Production of multigene transgenic pigs [4] | Demonstrates capacity for complex genetic modification. |

| Biomedical Research | Creation of large animal models for human diseases | Various transgenic pig models [1] [4] | Pigs are physiologically closer to humans than rodents. |

Quantitative Data and Efficiency

The efficiency of SMGT is a critical factor for its practical application. While it boasts advantages in cost and simplicity, its overall efficiency is often reported as low, though it can vary significantly.

Table 2: SMGT Efficiency and Performance Metrics

| Metric | Reported Value/Range | Context and Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transgenic Efficiency | 5% to 60% | Broad range observed in pig transgenesis [4]. | Lavitrano et al. |

| Transgene Transmission (F0 to F1) | ~25% | Only a quarter of initial studies demonstrated heritability beyond the founder generation [1]. | Smith & Spadafora, 2005 |

| Phenotype Modification Rate | Up to 80% | Frequency of observed phenotype changes in some experiments can be high [1]. | Smith & Spadafora, 2005 |

The low efficiency is primarily attributed to the poor uptake of exogenous DNA by sperm cells, which reduces the number of oocytes fertilized by transfected spermatozoa [1]. Furthermore, for a technique to be considered successful in animal transgenesis, the transgene must be stably transmitted to subsequent generations (F1, F2, etc.), a hurdle that many early claims of SMGT did not clear [1].

Comparative Analysis with Other Transgenic Techniques

In modern pig breeding, SMGT is one of several available techniques. Comparing it with other methods highlights its relative advantages and limitations.

Table 3: SMGT vs. Other Transgenic Techniques in Pigs

| Technique | Key Principle | Relative Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) | Sperm cells bind and internalize exogenous DNA for delivery during fertilization. | 5-60% [4] | Low cost, simple procedure, no embryo handling or specialized equipment needed [3] [4]. | Low and inconsistent DNA uptake, controversy around reliability, presence of natural barriers [1]. |

| Pronuclear Microinjection (PNI) | DNA construct is microinjected into the pronucleus of a fertilized egg. | ~1% [4] | Was the traditional standard method. | Low efficiency, requires many embryos, high operational skill, causes mechanical damage [4]. |

| Cytoplasmic Injection (CI) | DNA transposon systems are injected into the cytoplasm of fertilized eggs. | >8% [4] | Simpler than PNI, less mechanical damage [4]. | Relies on timing of nuclear membrane fusion [4]. |

| Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | Nuclei from genetically modified somatic cells are transferred into enucleated oocytes. | 0.5-1% (for livestock) [4] | Allows for in vitro screening of modified cells before embryo production, enabling more complex edits [4]. | Technically complex, generally low efficiency, concerns about animal health [4]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful SMGT protocol requires specific reagents and materials to facilitate the binding of DNA to sperm and ensure subsequent fertilization and embryo development.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for SMGT Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in SMGT Protocol | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Processed Spermatozoa | The primary biological vector for exogenous DNA. | Semen must be extensively washed to remove inhibitory factors in seminal plasma [1]. |

| Exogenous DNA Construct | The genetic material to be transferred into the embryo. | Can be linear or circular DNA; size and purity can affect efficiency [1] [4]. |

| DNA-Binding Proteins (DBPs) | Mediate the specific binding of DNA to the sperm cell membrane. | Naturally present on sperm head surface; their activity is unlocked by seminal plasma removal [1]. |

| Washing Buffers | To remove seminal plasma and prepare sperm for DNA uptake. | Typically protein-free media to prevent interference with DNA-sperm interaction. |

| Fertilization Media | To support the union of DNA-loaded sperm and oocytes. | Standard in vitro fertilization (IVF) media can be used post-incubation [4]. |

| Embryo Culture Media | To support the development of fertilized embryos post-IVF. | Supports the early-stage transgenic embryos before transfer [4]. |

Sperm-mediated gene transfer represents a conceptually simple and cost-effective alternative to more complex transgenic technologies for the production of genetically modified pigs. While it has proven successful in generating transgenic pig models for biomedical research and agricultural improvement, its path to becoming a reliable, mainstream methodology is hampered by inconsistent efficiency and ongoing controversy regarding its fundamental mechanisms. Future research aimed at better understanding and controlling the interactions between sperm and exogenous DNA, particularly how to consistently overcome natural biological barriers, will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of SMGT in porcine molecular breeding.

The production of transgenic pigs is a cornerstone of biomedical and agricultural research, enabling advancements in xenotransplantation, disease modeling, and livestock improvement. Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) represents a pivotal methodology in the historical development of transgenic technology. First conceptualized as a technique leveraging the innate ability of spermatozoa to internalize exogenous DNA, SMGT provides a simplified and efficient alternative to more complex and equipment-intensive methods like pronuclear microinjection (PNI) and Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) [5]. Its application has evolved from early proof-of-concept studies to a validated protocol for generating pigs with targeted genetic modifications. This document details the application notes and experimental protocols for SMGT, framing it within a broader thesis on its role for transgenic pig production.

Comparative Analysis of Transgenic Techniques

The evolution of pig transgenesis has been driven by several core technologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Table 1 provides a comparative overview of these key methods.

Table 1: Key Techniques for Generating Transgenic Pigs

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Reported Transgenic Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronuclear Microinjection (PNI) | Physical microinjection of DNA construct into a pronucleus of a fertilized egg [5]. | Established history; does not require cell culture. | Low efficiency (~1%); random transgene integration; high mechanical damage; requires specialized equipment [5]. | ~1% (number of transgenic pigs/injected embryos transferred) [5]. |

| Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | Transfer of a nucleus from a genetically modified somatic cell into an enucleated oocyte [6] [5]. | Enables pre-selection of modified cell clones; ensures precise genetic modifications and high transgene positivity rate [6] [5]. | Technically complex; low overall efficiency (0.5-1% for modifying somatic cells); associated with placental and fetal abnormalities [5]. | High positivity rate in offspring due to pre-screening, but low live birth rate per embryo transferred [5]. |

| Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) | Incubation of sperm cells with exogenous DNA, followed by artificial insemination or in vitro fertilization [5]. | Simple procedure; no expensive equipment required; high potential efficiency [5]. | Variable efficiency (5-60%); inconsistency in DNA uptake and integration; potential for mosaicism [5]. | 5% to 60%, highly dependent on protocol optimization [5]. |

SMGT Protocol for Transgenic Pig Production

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for the production of transgenic pigs via SMGT, incorporating best practices and key considerations for researchers.

Reagents and Equipment

Reagents:

- Porcine spermatozoa (fresh or frozen-thawed from a proven boar)

- Exogenous DNA construct (e.g., linearized plasmid, Sleeping Beauty or piggyBac transposon system)

- Sperm wash medium (e.g., Dulbecco's PBS supplemented with BSA)

- Capacitation-inducing agents (e.g., heparin, bicarbonate)

- In vitro fertilization (IVF) medium or artificial insemination medium

- Antibiotics (Penicillin-Streptomycin)

Equipment:

- Standard cell culture incubator (38.5°C, 5% CO₂)

- Benchtop centrifuge

- Laminar flow hood

- Hemocytometer or automated cell counter

- Instrument for artificial insemination or materials for in vitro fertilization

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Sperm Preparation and Washing

- Collect and pool semen from multiple fertile boars. Alternatively, use frozen-thawed semen from a commercial source.

- Wash spermatozoa twice in sperm wash medium by centrifugation at 500 x g for 10 minutes to remove seminal plasma, which contains nucleases that can degrade the exogenous DNA.

- Resuspend the final sperm pellet in a suitable incubation medium to a concentration of 1-5 x 10ⶠsperm/mL.

Step 2: Incubation with Exogenous DNA

- Dilute the purified exogenous DNA construct in the same incubation medium. The optimal final DNA concentration typically ranges from 1 to 10 ng/µL and should be determined empirically.

- Incubate the prepared sperm suspension with the DNA solution for a defined period (e.g., 15 minutes to 2 hours) at 38.5°C. Some protocols include a brief exposure to a mild detergent (e.g., Triton X-100) or lipofectamine to enhance DNA uptake, though this can compromise sperm viability and requires careful optimization.

Step 3: Removal of Unbound DNA

- After incubation, pellet the sperm cells by gentle centrifugation.

- Wash the sperm pellet once with medium to remove any unincorporated, free-floating DNA.

- Resuspend the sperm in pre-warmed IVF medium for immediate use.

Step 4: Fertilization and Embryo Transfer

- Option A: In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Co-incubate the DNA-loaded sperm with in vitro-matured porcine oocytes for 5-6 hours. Subsequently, wash the presumptive zygotes to remove excess sperm and culture them in vitro until the desired stage for embryo transfer.

- Option B: Artificial Insemination (AI): Use the DNA-loaded sperm suspension for surgical or non-surgical artificial insemination of synchronized sows. This method is less common but has been reported [5].

- Transfer the resulting embryos (from IVF) into the oviducts of synchronized surrogate sows. The number of embryos transferred per surrogate should follow standard institutional protocols (e.g., 30-50 embryos per surrogate).

Step 5: Genotyping and Analysis

- After farrowing, collect tissue samples (e.g., ear notch or tail clip) from the piglets.

- Extract genomic DNA and screen for the presence of the transgene using PCR, Southern blot, or other appropriate molecular techniques.

- For positive founders, conduct further analyses to determine transgene copy number, integration site, and expression levels.

Current Applications and Outcomes

SMGT has been successfully applied to create multi-transgenic pigs. For instance, one study demonstrated the simultaneous introduction of three fluorescent reporter genes using this technique [5]. In the context of xenotransplantation, SMGT was used to create pig lines expressing the human decay accelerating factor (hDAF), a key protein that helps protect transplanted tissues from complement-mediated rejection [5]. The efficiency of SMGT can be highly variable, with reported transgene positivity rates in offspring ranging from 5% to 60%, underscoring the need for rigorous protocol standardization [5]. The technique's primary advantage lies in its simplicity and accessibility, as it bypasses the need for sophisticated micromanipulation equipment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2 outlines essential reagents and their critical functions in the SMGT workflow, providing a quick reference for laboratory setup.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SMGT

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in SMGT Protocol |

|---|---|

| Sperm Wash Medium | Removes seminal plasma and protects sperm during centrifugation, preventing DNA degradation. |

| Exogenous DNA Construct | Carries the genetic material of interest (e.g., a therapeutic gene or a fluorescent reporter). |

| Transposon Systems (e.g., Sleeping Beauty, piggyBac) | Facilitates more stable and precise integration of the transgene into the host genome, improving expression and reducing positional effects [5]. |

| Capacitation-Inducing Agents | Mimics the natural physiological process that prepares sperm for fertilization, which can also enhance DNA uptake. |

| In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) Medium | Supports the fertilization process and subsequent early embryonic development in vitro. |

| Cdk8-IN-14 | Cdk8-IN-14|CDK8 Inhibitor|For Research Use |

| Icmt-IN-13 | Icmt-IN-13, MF:C21H25ClFNO, MW:361.9 g/mol |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core SMGT workflow and its context within the broader transgenic development pipeline.

SMGT Experimental Workflow

Transgenic Pig Development Pathway

This application note provides a detailed technical comparison of Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) against two established methods—Pronuclear Microinjection (PNI) and Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT)—for the production of transgenic pigs. Framed within broader thesis research on optimizing SMGT protocols, this document summarizes quantitative performance data, outlines detailed experimental methodologies, and identifies essential research reagents. The content is designed to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the most appropriate genetic engineering strategy for their projects.

The generation of transgenic pigs is a critical technology for biomedical research and agricultural science, enabling the study of human diseases, the production of pharmaceutical proteins, and the enhancement of livestock traits [7] [5]. The selection of an optimal gene transfer method is paramount to the success and efficiency of these endeavors. While Pronuclear Microinjection (PNI) and Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) have been foundational techniques, Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) presents a compelling alternative that leverages the natural ability of spermatozoa to internalize and deliver exogenous DNA into the oocyte during fertilization [7] [5]. This document provides a structured comparison of these three key technologies, with a specific focus on their application in transgenic pig production.

Comparative Analysis of Key Techniques

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of PNI, SCNT, and SMGT, highlighting the distinct advantages of the SMGT protocol.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Transgenesis Techniques in Pig Production

| Feature | Pronuclear Microinjection (PNI) | Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Direct microinjection of DNA into the pronucleus of a fertilized oocyte [7] [8] | Transfer of a nucleus from a genetically modified somatic cell into an enucleated oocyte [7] [9] | Use of sperm cells as natural vectors to carry exogenous DNA during fertilization [7] [5] |

| Integration Site | Random [7] | Can be predefined via cell culture screening [9] | Random [5] |

| Typical Efficiency (Transgenic Offspring) | ~1% [5] | High (theoretically 100% from pre-screened cells) [9] | 5% to 60% [5] |

| Key Advantage | Well-established history [10] | Pre-selection of modified cells; potential for gene targeting [7] [9] | No complex equipment or embryo manipulation; high throughput potential [5] |

| Primary Limitation | Low efficiency; random integration; technically demanding [7] [5] | Very low live birth rate (1-3%); epigenetic abnormalities [7] [11] [9] | Instability of DNA-sperm interaction; variable efficiency [5] |

| Technical Skill & Equipment | Requires highly trained personnel and sophisticated micromanipulation equipment [5] [8] | Requires advanced cell culture and micromanipulation skills [7] | Relatively simple; requires standard artificial insemination or in vitro fertilization lab setup [5] |

| Handling of Embryos | Extensive in vitro manipulation of zygotes [7] | Complex in vitro manipulation of oocytes and reconstructed embryos [12] | Minimal; utilizes standard fertilization procedures [5] |

Table 2: Quantitative Data Comparison for Transgenic Pig Production

| Parameter | Pronuclear Microinjection (PNI) | Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transgene Positivity Rate in Offspring | Low (~1%) [5] | Very High (theoretically 100%) [9] | Variable (5-60%) [5] |

| Mosaicism in Founders | High prevalence [9] | Absent (all cells are transgenic) [9] | Can occur [7] |

| Cost and Resource Intensity | High (costly equipment, skilled staff, many embryos needed) [7] [5] | Very High (complex procedures, low overall live birth rate) [7] [9] | Low (minimal specialized equipment or reagents) [5] |

| Developmental Abnormalities | Not typically associated | High (due to incomplete nuclear reprogramming) [7] [11] | Not typically associated |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) in Pigs

Principle: This protocol exploits the innate ability of sperm cells to bind and internalize exogenous DNA, which is then delivered to the oocyte upon fertilization to generate transgenic embryos [5].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sperm Collection and Preparation:

- Collect fresh semen from a boar of known fertility. Alternatively, use frozen-thawed semen from a commercial source.

- Wash spermatozoa twice by centrifugation (800 x g for 10 minutes) in a non-capacitating medium, such as Dulbecco's Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) supplemented with 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) to remove seminal plasma.

- Resuspend the final sperm pellet to a concentration of 1-5 x 10^6 sperm/mL in a defined fertilization medium.

Interaction with Exogenous DNA:

- Incubate the prepared sperm suspension with the linearized, foreign DNA construct (10-100 ng/μL final concentration) for 30-60 minutes at 37°C under 5% CO₂ [5]. To enhance DNA uptake, consider using specific agents like dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or lipofectamine during this step.

- Post-incubation, wash the sperm cells again to remove any unbound DNA.

Fertilization:

- For In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Add the DNA-loaded sperm suspension to in vitro-matured porcine oocytes in fertilization medium. Co-incubate for 6-18 hours at 38.5°C under 5% CO₂ and 5% O₂.

- For Artificial Insemination (AI): The DNA-loaded sperm preparation can be used for direct intrauterine artificial insemination of synchronized sows [5].

Embryo Culture and Transfer:

- For IVF-derived embryos, remove the presumptive zygotes from the fertilization drops, wash to remove excess sperm, and culture in a defined embryo culture medium (e.g., PZM-3) for 5-7 days until the blastocyst stage.

- Select developmentally competent embryos for surgical transfer into synchronized recipient gilts.

Genotyping of Offspring:

- After birth, collect tissue samples (e.g., ear notch or tail clip) from the founder piglets (F0).

- Extract genomic DNA and screen for the presence and integration of the transgene using PCR, Southern blot analysis, or next-generation sequencing.

Protocol for Pronuclear Microinjection (PNI) in Pigs

Principle: A DNA construct is physically injected directly into the larger male pronucleus of a fertilized, one-cell embryo (zygote), leading to random integration into the host genome [7] [13].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Zygote Collection:

- Collect fertilized one-cell embryos (zygotes) from super-ovulated sows or via in vitro fertilization. The pronuclei are often not visible in pig zygotes due to cytoplasmic lipids.

Preparation for Microinjection:

- Centrifuge zygotes at 12,000-15,000 x g for 5-10 minutes to force cytoplasmic organelles to the periphery, making the pronuclei more visible [5].

- Prepare a microinjection needle filled with the DNA solution (1-2 ng/μL in injection buffer, e.g., Tris-EDTA). Place a drop of manipulation medium containing the zygotes on an inverted microscope equipped with micromanipulators.

Microinjection:

- Immobilize a zygote using a holding pipette. Insert the injection pipette through the zona pellucida and the oolemma into the larger male pronucleus.

- Deliver a precise volume of DNA solution (1-2 picoliters) until visible swelling of the pronucleus occurs (~1-2% of its volume). Withdraw the pipette carefully [13].

Embryo Culture and Transfer:

- Wash the injected zygotes and culture them in vitro for 1-3 days to assess viability and initial cleavage. Embryos that develop normally to the 2- to 4-cell stage are selected.

- Surgically transfer viable embryos into the oviduct of a synchronized recipient gilt.

Founder Analysis:

- Screen offspring for transgene integration. Due to frequent mosaicism, analyze tissues from multiple lineages and breed founders to confirm germline transmission [9].

Protocol for Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) in Pigs

Principle: The genetic material of an unfertilized oocyte is removed and replaced with the nucleus from a somatic cell that has been genetically modified in culture, resulting in a cloned, transgenic embryo [7] [9].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Genetic Modification of Donor Cells:

- Isolate and culture somatic cells, typically fetal fibroblasts. Transfect these cells with the desired DNA construct using electroporation or lipofection.

- Apply drug selection (e.g., G418 for neomycin resistance) to select stably transfected clones. Expand and validate modified cells for transgene integration and expression via PCR, Southern blot, or other assays [9].

Oocyte Enucleation:

- Collect in vivo- or in vitro-matured oocytes at the Metaphase II (MII) stage. Remove the chromosomal spindle complex (enucleation) using a micropipette under microscopic visualization, often facilitated by fluorescent staining or polarized light microscopy.

Nuclear Transfer:

- Insert a single, genetically modified donor cell (or its nucleus) into the perivitelline space of the enucleated oocyte, directly in contact with the oocyte's cytoplasm.

Fusion and Activation:

- Fuse the donor cell with the enucleated oocyte using electrical pulses or viral fusogens. This fusion event also introduces factors from the oocyte cytoplasm that begin reprogramming the donor nucleus.

- Simultaneously or shortly after fusion, artificially activate the reconstructed oocyte to initiate embryonic development, typically using a combination of chemical agents like ionomycin and 6-DMAP, or specific inhibitors [11].

Embryo Culture and Transfer:

- Culture the successfully activated SCNT embryos in a defined medium for 1-6 days. Monitor development to the blastocyst stage.

- Transfer developmentally competent embryos into the uterus of a synchronized recipient gilt.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transgenic Pig Production

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm Washing Medium | Removes seminal plasma and decapacitation factors to prepare sperm for DNA uptake [5]. | Initial preparation of boar sperm for SMGT. |

| DNA Transfection Reagents | Enhances the binding and internalization of exogenous DNA into sperm cells. | Added during the sperm-DNA co-incubation step in SMGT. |

| Holding and Injection Pipettes | Essential microtools for precise manipulation and injection of zygotes and oocytes. | Used for pronuclear microinjection (PNI) and enucleation/cell transfer in SCNT. |

| Manipulation Medium | A specific culture medium designed to maintain embryo viability outside the incubator during micromanipulation. | Used for all procedures performed on a microscope stage (PNI, SCNT). |

| Fusion/Activation Media | Contains components to induce cell fusion and trigger embryonic development in SCNT embryos. | Applied after donor cell transfer in SCNT to create a reconstructed, activated embryo [11]. |

| Defined Embryo Culture Medium | Supports the in vitro development of embryos from the one-cell stage to the blastocyst. | Used for culturing embryos post-manipulation (all three techniques) before transfer. |

| Drug Selection Agents | Selects for somatic cells that have successfully integrated the transgene during culture. | Added to the media of donor cells in the SCNT workflow to create a pure population of transgenic cells [9]. |

| Lamotrigine-13C2,15N2,d3 | Lamotrigine-13C2,15N2,d3, MF:C9H9Cl2N5, MW:265.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sparfloxacin-d5 | Sparfloxacin-d5 Stable Isotope | Sparfloxacin-d5 (CI-978-d5) is a deuterated bacterial inhibitor for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The choice between SMGT, PNI, and SCNT for generating transgenic pigs depends heavily on the project's specific goals, available resources, and technical expertise. SMGT offers a less technically demanding and potentially high-efficiency alternative that avoids extensive embryo manipulation. PNI remains a direct but inefficient method, while SCNT, despite its complexity and low overall efficiency, provides unparalleled control by allowing for pre-selection of specific genetic modifications. Researchers must weigh these key advantages and limitations carefully to successfully advance their work in porcine transgenesis.

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) presents a powerful methodology for generating transgenic animals, offering a simpler and more efficient alternative to complex techniques like pronuclear microinjection. Within the context of transgenic pig production—a critical field for biomedical applications such as xenotransplantation and disease modeling—SMGT leverages the innate ability of sperm cells to bind and internalize exogenous DNA. This protocol details the core principles and molecular mechanisms governing the spontaneous uptake of foreign DNA by spermatozoa, providing a foundational framework for researchers aiming to utilize SMGT in porcine transgenesis. The ensuing application notes outline a standardized, reproducible experimental workflow based on these principles [14].

Molecular Mechanism of DNA Uptake

The interaction between sperm cells and exogenous DNA is not a casual event but a controlled process mediated by specific ionic interactions and protein-DNA recognition. Understanding this mechanism is paramount for optimizing SMGT efficiency [15] [14].

Key DNA-Binding Proteins

Southwestern blot analysis of sperm head protein extracts has identified specific classes of DNA-binding proteins that act as substrates for exogenous DNA. The major protein classes involved are summarized in Table 1 below [15].

Table 1: Major DNA-Binding Protein Classes in Spermatozoa

| Protein Class (Molecular Weight) | Conservation Across Species | Accessibility in Intact Cells | Postulated Role in DNA Uptake |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~50 kDa | Variable | Not accessible | Potential secondary substrate |

| 30-35 kDa | High | Accessible | Primary DNA receptor |

| <20 kDa (includes protamines) | Variable | Not accessible | Nuclear packaging |

The 30-35 kDa protein class is of particular importance. It is highly conserved among mammalian species and represents the only class of DNA-binding proteins accessible to exogenous DNA in intact, viable sperm cells. Purified 30-35 kDa proteins interact with DNA in vitro, forming discrete protein/DNA complexes as confirmed by band shift assays. This evidence strongly supports their role as the primary receptor for exogenous DNA on the sperm surface [15] [14].

The Process of Uptake and Localization

Epididymal sperm cells spontaneously take up exogenous DNA during a brief incubation period of 15-20 minutes. The DNA is specifically and reversibly localized to the nuclear area of the sperm head. The binding is ionic; it can be competed out by an excess of cold competitor DNA or other polyanions like heparin and dextran sulfate. Conversely, polycations like poly-L-lysine favor DNA uptake. Furthermore, sperm cells show a preference for larger DNA molecules (e.g., 7 kb) over smaller fragments (150-750 bp) [14].

Regulatory Inhibition by Seminal Plasma

A critical factor controlling DNA uptake is the presence of a powerful inhibitory factor in the seminal plasma of mammals. This factor blocks the binding of exogenous DNA to sperm cells and is effective even across species (heterologous inhibition). The 30-35 kDa DNA-binding proteins are the specific target of this inhibition, losing their DNA-binding capability in the presence of the seminal plasma factor. Therefore, for successful SMGT, it is essential to use sperm prepared from epididymides, effectively washed to remove any trace of seminal plasma [15] [14].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential molecular mechanism of exogenous DNA uptake by spermatozoa and its key regulatory point.

Quantitative Data on DNA-Sperm Interaction

The efficiency of DNA uptake is influenced by several physical and molecular factors. The key quantitative parameters characterizing this interaction are consolidated in Table 2 below [14].

Table 2: Key Parameters of Exogenous DNA Uptake by Spermatozoa

| Parameter | Experimental Findings | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Uptake Time Course | 15-20 minutes | Saturation is reached within this timeframe. |

| DNA Size Preference | Preferential uptake of larger molecules (e.g., 7 kb) | Uptake of smaller fragments (150-750 bp) is less efficient. |

| Binding Affinity | Reversible binding | DNA can be displaced by excess competitor DNA or polyanions. |

| Cellular Localization | Specific localization to the nuclear area of sperm head | Determined by autoradiography and fluorescence. |

| Critical Step | Removal of seminal plasma | Seminal plasma contains a potent inhibitory factor. |

Experimental Protocol: DNA Uptake and Validation

This protocol describes the foundational steps for loading exogenous DNA onto porcine spermatozoa for SMGT applications, based on the elucidated core principles.

Sperm Preparation and DNA Binding Assay

Objective: To prepare sperm free of seminal plasma inhibitors and facilitate binding of exogenous plasmid DNA.

Materials:

- Porcine Epididymal Sperm: Collected from cauda epididymides.

- DNA Construct: Plasmid DNA of interest (e.g., for xenotransplantation antigens like GGTA1).

- Wash Buffer: Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS).

- Binding Medium: DPBS supplemented with 6 mg/mL BSA.

- Poly-L-lysine (optional, to enhance uptake).

Procedure:

- Sperm Collection: Mince porcine cauda epididymides in pre-warmed DPBS and filter the suspension through a nylon mesh to remove tissue debris.

- Washing: Centrifuge the sperm suspension at 500 x g for 10 minutes. Resuspend the sperm pellet in 1 mL of Binding Medium. Repeat this wash step twice to ensure complete removal of seminal plasma components.

- DNA Incubation: Adjust the sperm concentration to 1-5 x 10^7 cells/mL in Binding Medium. Add the plasmid DNA at a final concentration of 1-5 µg/mL. Incubate the mixture for 20 minutes at room temperature or 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Removal of Unbound DNA: Pellet the sperm cells by centrifugation at 500 x g for 10 minutes. Carefully remove the supernatant containing unbound DNA. Wash the pellet once with Binding Medium to remove any residual unbound DNA.

- Validation of Uptake (Optional): Resuspend a small aliquot of the sperm pellet for analysis. DNA binding can be validated using:

- Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) with labeled DNA probes.

- PCR on washed sperm samples to detect the presence of the transgene.

Assessing Sperm DNA Integrity Post-Uptake

Objective: To evaluate the DNA fragmentation index (DFI) of sperm post-DNA uptake, as high DFI can compromise the success of subsequent fertilization and embryo development [16] [17].

Materials:

- Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay Kit

- Flow Cytometer or Fluorescence Microscope

- DPBS

Procedure:

- After the final wash, fix the DNA-loaded sperm cells in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes.

- Permeabilize the cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 in DPBS for 5 minutes on ice.

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions for the TUNEL assay to label DNA strand breaks.

- Analyze the samples by flow cytometry. Calculate the DFI as the percentage of TUNEL-positive sperm in the population.

- Interpretation: A high DFI is inversely correlated with sperm motility, normal morphology, and fertility outcomes in assisted reproductive technologies. Sperm with a DFI > 30% may lead to significantly reduced embryo development rates [17].

The following workflow diagram integrates the core protocol with quality control measures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of SMGT relies on a suite of specific reagents. Table 3 lists critical materials and their functions for DNA uptake experiments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SMGT DNA Uptake Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Porcine Epididymal Sperm | Source of male gametes; must be free of seminal plasma to avoid inhibition of DNA uptake. |

| Plasmid DNA Construct | Exogenous DNA carrying the gene of interest (e.g., for knockout of xenoantigens like GGTA1, CMAH, B4GALNT2 [18]). |

| Binding Medium (BSA) | Provides a protein-rich environment to maintain sperm viability during the DNA incubation step. |

| Poly-L-lysine | Polycation that enhances DNA uptake by strengthening ionic interactions with the sperm surface [14]. |

| Heparin / Dextran Sulfate | Polyanions used as competitive inhibitors in control experiments to confirm specificity of DNA binding [14]. |

| TUNEL Assay Kit | Validates sperm DNA integrity post-uptake; high DFI indicates poor sperm quality and predicts low fertility [17]. |

| PCR Reagents | Molecular validation of transgene association with washed sperm cells. |

| Arginase inhibitor 7 | |

| Sulfasalazine-d3,15N | Sulfasalazine-d3,15N, MF:C18H14N4O5S, MW:402.4 g/mol |

Application Notes in Transgenic Pig Production

The principles outlined herein are directly applicable to modern pig transgenesis for xenotransplantation. Current research employs somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) using genetically engineered fibroblasts as the primary method for generating multi-gene edited pigs. However, SMGT remains a valuable and simpler technique for rapid proof-of-concept studies or introducing less complex genetic modifications [18].

When designing DNA constructs for SMGT, researchers should consider edits that reduce xenograft immunogenicity. Key targets include:

- Knockout of Glycosyltransferases: Inactivation of genes like GGTA1 (α-Gal), CMAH (Neu5Gc), and B4GALNT2 to remove major xenoantigens recognized by human pre-formed antibodies [18].

- Expression of Human Complement Regulators: Incorporation of transgenes like hCD46, hCD55, and hCD59 to protect pig cells from human complement-mediated lysis [18].

Efficiency in producing viable founders depends not only on successful DNA uptake but also on maintaining high sperm quality. Rigorous assessment of sperm motility, morphology, and DNA fragmentation index (DFI) post-uptake is crucial, as these parameters are strongly correlated with successful embryo development and live births [17].

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) represents a pioneering methodology within transgenic pig production research, enabling researchers to overcome fundamental reproductive isolation barriers that traditionally limit genetic exchange between species. This technique leverages the innate capacity of spermatozoa to internalize and deliver foreign DNA into oocytes during fertilization, thereby creating genetically modified embryos. Within the broader context of transgenic livestock development, SMGT provides a relatively efficient and technically accessible approach compared to more complex methods such as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) or pronuclear microinjection. The technique holds particular promise for agricultural biotechnology, pharmaceutical production, and biomedical research, including the development of pig models for human disease and xenotransplantation [19] [20].

Recent advances in genetic engineering have further enhanced SMGT's potential. The development of SynNICE (Synthetic Nucleus Injection into Cell Embryos) technology enables the transfer of megabase-scale human DNA sequences into other species, representing a quantum leap in overcoming reproductive isolation barriers. This approach has successfully demonstrated the delivery of a 1.14 Mb human Y chromosome fragment (AZFa region) into mouse early embryos, establishing a groundbreaking platform for cross-species genetic transfer that could be adapted to porcine systems [21]. The ability to synthesize, assemble, and transfer such large genetic constructs opens new possibilities for creating transgenic pigs with humanized physiological systems for biomedical applications.

Quantitative Comparison of Genetic Transfer Techniques

Transgenic pig production employs multiple technical approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The following table summarizes the key methodologies used to overcome reproductive isolation in pig genetic engineering:

Table 1: Comparison of Genetic Transfer Techniques for Transgenic Pig Production

| Technique | Key Features | Efficiency | Insert Size Capacity | Technical Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) | Uses sperm as natural vector for DNA uptake; can be enhanced with electroporation or magnetic fields | Moderate | Limited (typically plasmid DNA) | Low to Moderate |

| Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | Transfer of somatic nucleus into enucleated oocyte; enables precise genetic modifications | Low to Moderate | Virtually unlimited (whole genome) | High |

| ICSI-Mediated Gene Transfer | Direct injection of DNA with sperm into oocyte | Moderate | Limited (typically plasmid DNA) | High |

| Retroviral Vector Transduction | Uses modified viruses to deliver genes | High | Limited by viral packaging capacity | Moderate |

| SynNICE Technology | Transfer of synthetic megabase-scale DNA via yeast nuclear carriers | Demonstrated in mice; porcine adaptation pending | Very High (megabase scale) | Very High |

The quantitative comparison reveals that SMGT occupies a unique position in the transgenic technology landscape, offering a balance between technical accessibility and practical applicability. While newer approaches like SynNICE technology offer unprecedented capacity for large DNA fragment transfer, SMGT remains particularly valuable for applications requiring routine genetic modifications without specialized equipment [19] [21] [20]. The integration efficiency of SMGT can be significantly enhanced through optimization of DNA uptake conditions, including the use of specific electroporation parameters and the selection of donor boars with higher natural DNA uptake capabilities [19].

SMGT Protocol for Transgenic Pig Production

Critical Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of SMGT requires careful preparation of specific reagents and materials. The following table outlines the essential components of the "Researcher's Toolkit" for SMGT experiments:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SMGT Protocol

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Sperm | DNA vector carrier | Selected boars with high DNA uptake capacity [19] |

| Foreign DNA Construct | Genetic material for transfer | High-quality plasmid DNA with appropriate regulatory elements |

| Electroporation Buffer | Facilitate DNA uptake | Optimized ionic composition with minimal cytotoxicity |

| Transfection Enhancers | Increase membrane permeability | Compounds such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or specific lipids |

| In Vitro Maturation Media | Oocyte preparation | TCM-199 with FSH, LH, EGF, and cysteine [22] |

| Embryo Culture Media | Post-fertilization development | Sequential media supporting early embryonic development |

Detailed Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive SMGT workflow for transgenic pig production:

Step-by-Step Protocol Implementation

Sperm Preparation and DNA Loading

Sperm Collection and Selection: Collect semen from proven donor boars using standard artificial insemination protocols. Select boars with demonstrated high DNA uptake capacity, as significant individual variation exists [19] [20]. Wash sperm samples to remove seminal plasma using a discontinuous density gradient centrifugation system.

DNA Processing and Complex Formation: Prepare high-purity plasmid DNA containing the transgene of interest. For optimal results, linearize the DNA construct and resuspend in TRIS-EDTA buffer at a concentration of 0.1-1.0 μg/μL. The DNA can be pre-incubated with lipofection agents to facilitate membrane passage, though this requires optimization for different sperm batches.

DNA Uptake via Electroporation: Mix 10-20 million motile sperm with 5-10 μg of DNA in electroporation buffer. Perform electroporation using optimized parameters: square wave pulses, field strength of 600-800 V/cm, and pulse duration of 1-5 ms [19]. Immediate assessment of sperm viability post-electroporation is critical, as excessive electrical parameters can compromise membrane integrity and fertilization capacity.

Oocyte Preparation and In Vitro Maturation

Oocyte Collection: Obtain ovaries from slaughterhouses and transport to the laboratory in sterile physiological saline at 39°C. Aspirate follicles (3-6 mm diameter) using an 18-gauge needle attached to a 10 mL syringe. Collect oocytes surrounded by a compact, multilayer cumulus cell mass (cumulus-oocyte complexes, COCs) [22].

In Vitro Maturation (IVM): Wash COCs three times in maturation medium (TCM-199 supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 ng/mL EGF, 10 IU/mL FSH, 10 IU/mL LH, and 0.1 mM cysteine). Culture groups of 50-70 COCs in 500 μL maturation medium under mineral oil at 39°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere with saturated humidity for 42-44 hours [22].

Oocyte Assessment and Preparation: After maturation, denude oocytes by gentle pipetting in 1 mg/mL hyaluronidase solution. Select only metaphase II oocytes exhibiting a distinct first polar body for fertilization experiments.

Fertilization and Embryo Transfer

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Co-incubate DNA-loaded sperm (1-2 × 10ⵠsperm/mL) with matured oocytes in fertilization medium for 6-8 hours. Subsequently, remove excess sperm and transfer presumptive zygotes to fresh culture medium.

Embryo Culture and Selection: Culture embryos for 5-6 days until the blastocyst stage. Monitor embryonic development carefully, noting any developmental delays or abnormalities. Screen blastocysts for transgene integration using PCR or other molecular techniques before transfer.

Embryo Transfer: Synchronize recipient gilts or sows hormonally. Surgically transfer 30-50 developing embryos to the oviducts of each recipient on day 1 after estrus detection [19]. Monitor pregnancy status via ultrasound around day 28-35 post-transfer.

Advanced Technical Considerations and SynNICE Integration

Enhancing SMGT Efficiency

Several technical factors critically influence SMGT efficiency. Sperm quality and viability after DNA loading represent the most significant determinants of success. While electroporation enhances DNA uptake, it can simultaneously reduce sperm motility and membrane integrity. Optimization must balance these competing factors through systematic parameter testing. The DNA-sperm incubation conditions (time, temperature, and media composition) also significantly impact internalization efficiency. Some protocols incorporate short-duration, high-intensity electromagnetic pulses to transiently increase membrane permeability without irreversible damage [19].

The selection of donor boars with inherently higher DNA uptake capacity provides another optimization avenue. Research indicates substantial individual variation in this trait, with some boars demonstrating consistently superior performance as DNA vectors [20]. Establishing a screening protocol to identify such individuals can dramatically improve overall SMGT efficiency.

Integration with SynNICE Technology for Complex Genetic Modifications

The emerging SynNICE technology offers a revolutionary approach that could complement traditional SMGT for sophisticated genetic engineering applications. This method involves:

Megabase DNA Assembly: Utilizing yeast homologous recombination systems to assemble megabase-scale human DNA sequences through a hierarchical strategy. This approach successfully assembled the highly repetitive (69.38% repeats) 1.14 Mb human AZFa region [21].

Yeast Nuclear Extraction: Developing techniques to isolate intact yeast nuclei containing the synthetic DNA while preserving chromatin structure. These nuclei can be cryopreserved for up to six months without degradation [21].

Cross-Species Delivery: Microinjecting the purified yeast nuclei into recipient oocytes or early embryos, enabling transfer of extremely large genetic constructs across species boundaries.

For transgenic pig production, SynNICE technology could enable the transfer of entire human gene clusters or regulatory domains to create more sophisticated humanized pig models. This approach shows particular promise for xenotransplantation research, where introducing large segments of human MHC genes could substantially reduce immune rejection barriers [21].

Alternative and Complementary Methods

While SMGT provides distinct advantages, researchers should consider complementary techniques for specific applications:

Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT): This approach involves transferring genetically modified somatic cell nuclei into enucleated oocytes. The protocol includes: (1) preparation of donor cells (typically fetal fibroblasts); (2) enucleation of in vitro-matured oocytes; (3) nuclear transfer; (4) artificial activation of reconstructed embryos; and (5) embryo culture and transfer [22]. SCNT enables precise genetic modifications in the donor cells before nuclear transfer, including gene knockouts using CRISPR/Cas9 systems.

ICSI-Mediated Gene Transfer: Intracytoplasmic sperm injection simultaneously delivers sperm and DNA directly into the oocyte cytoplasm, bypassing membrane barriers. This approach can be combined with SMGT principles by pre-incubating sperm with DNA before injection [19].

Lentiviral Transduction: Using engineered lentiviruses to deliver genetic material offers high transduction efficiency but is limited by insert size constraints and potential safety concerns [19].

SMGT represents a powerful methodology for overcoming reproductive isolation barriers in transgenic pig production, offering a unique combination of technical accessibility and biological efficiency. The protocol detailed in this application note provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing this technology, from sperm preparation and DNA loading to embryo transfer and validation.

The ongoing development of advanced genetic transfer technologies, particularly the groundbreaking SynNICE platform for megabase-scale DNA synthesis and transfer, promises to further expand the possibilities for cross-species genetic engineering. These approaches will enable the creation of increasingly sophisticated porcine models for biomedical research, xenotransplantation, and agricultural innovation.

As the field progresses, the integration of SMGT with these emerging technologies will likely yield increasingly efficient and precise methods for genetic modification, ultimately enhancing our ability to address fundamental biological questions and develop novel therapeutic applications through transgenic animal models.

The Role of SMGT in Modern Molecular Breeding Programs

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) represents a transformative approach in the field of transgenesis, enabling the production of genetically engineered animals by utilizing spermatozoa as vectors for exogenous DNA. This method has emerged as a powerful alternative to conventional techniques like pronuclear microinjection, particularly in large animal models such as pigs. Within modern molecular breeding programs, SMGT facilitates the introduction of desirable traits—including disease resistance, improved feed efficiency, and enhanced production characteristics—in a manner that is both cost-effective and technically accessible [4]. The integration of SMGT into broader genetic improvement strategies is pivotal for advancing agricultural biotechnology, as it overcomes limitations associated with reproductive isolation and the lengthy timelines of traditional breeding [4]. This document details the application notes and experimental protocols for employing SMGT in transgenic pig production, providing researchers with a structured framework to implement this technology effectively.

SMGT Principles and Comparative Advantages

The fundamental principle of SMGT involves the innate capacity of sperm cells to bind, internalize, and transport exogenous DNA into the oocyte during fertilization, thereby facilitating the stable genomic integration of the transgene in the resulting offspring [4] [23]. This process leverages the natural biological functions of sperm, making it a less invasive and more streamlined methodology compared to other assisted reproductive technologies.

The comparative advantages of SMGT are particularly evident when evaluated against other established transgenesis techniques. The following table summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics of SMGT relative to pronuclear microinjection (PNI) and somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT).

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Methods for Producing Transgenic Pigs

| Method | Reported Transgenesis Efficiency | Key Technical Requirements | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMGT | Up to 80% integration rate; ~5-60% overall efficiency [4] [23] | Artificial insemination equipment, standard cell culture facilities | Low cost, technical simplicity, no complex equipment, suitable for multi-gene transfer [4] [23] | Potential variability in DNA uptake, need for optimized sperm preparation |

| Pronuclear Microinjection (PNI) | ~1% (number of transgenic pigs/injected embryos) [4] | Specialized micromanipulators, microinjectors, skilled personnel | Direct introduction of DNA into the pronucleus | Low efficiency, high mechanical damage to embryos, requires many embryos [4] |

| Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | High (due to pre-selection of modified cells) [4] [18] | Cell culture facility, micromanipulation equipment for nuclear transfer | Enables precise gene editing via pre-screened cell lines, high transgene positivity rate [4] [18] | Technically complex, very low overall efficiency, associated health issues in clones [4] |

As illustrated, SMGT offers a unique balance of high efficiency, operational simplicity, and cost-effectiveness, making it exceptionally suitable for large-scale applications in agricultural breeding and biomedical research, such as the generation of multi-transgene pigs for xenotransplantation [23].

Detailed SMGT Protocol for Transgenic Pig Production

This section provides a step-by-step protocol for generating transgenic pigs via SMGT, based on established methodologies with reported success in producing pigs expressing human genes like decay-accelerating factor (hDAF) [23].

Reagent and Material Preparation

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SMGT

| Item | Specification/Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Prepubertal synchronized gilts (e.g., Large White), selected boars [23] | Gilts synchronized with eCG and hCG; boars with proven fertility. |

| Sperm Preparation Medium | Swine Fertilization Medium (SFM) supplemented with BSA (6 mg/mL) [23] | SFM composition: Glucose (11.25 g/L), Sodium Citrate (10 g/L), EDTA (4.7 g/L), etc., pH 7.4. |

| Exogenous DNA Construct | Linearized plasmid DNA (e.g., pX-hDAF) | 0.4 μg per 10^6 sperm cells; linearized via restriction enzyme digestion (e.g., XhoI) to enhance integration [23]. |

| General Lab Equipment | Centrifuge, hemocytometer, water bath, standard artificial insemination supplies. | For sperm washing, counting, and insemination procedures. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram outlines the complete SMGT workflow, from sperm preparation to the genotyping of born piglets.

3.2.1 Sperm Collection and Washing

- Collect semen from trained boars. Remove seminal fluid by washing sperm in pre-warmed SFM supplemented with BSA [23].

- Centrifuge the sample at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 25°C. Aspirate the supernatant, resuspend the sperm pellet, and repeat the centrifugation step at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 17°C [23].

- Resuspend the final sperm pellet in SFM/BSA at room temperature and perform a cell count using a hemocytometer to adjust the concentration for the subsequent incubation step.

3.2.2 Sperm-DNA Incubation

- Dilute the washed sperm cells to a concentration of 1 × 10^9 cells in 120 mL of SFM/BSA maintained at 17°C [23].

- Add the linearized plasmid DNA at a concentration of 0.4 μg per 10^6 sperm cells [23].

- Incubate the sperm-DNA mixture for 2 hours at 17°C. Gently invert the flask every 20 minutes to prevent sperm sedimentation.

- For the final 20 minutes of incubation, bring the mixture to room temperature. Subsequently, heat the mixture at 37°C for 1 minute immediately prior to artificial insemination to enhance fertilization competence [23].

3.2.3 Artificial Insemination and Gestation

- Perform artificial insemination in prepubertal gilts that have been hormonally synchronized. Administration of 1,250 units of eCG followed by 750 units of hCG 60 hours later is a standard protocol [23].

- Inseminate the gilts at approximately 43 hours post-hCG injection using the entire prepared volume of DNA-treated sperm cells (1–1.5 × 10^9 sperm per gilt) [23].

- Allow pregnancy to proceed to term. Monitor the sows regularly throughout the gestation period.

3.2.4 Genotypic and Phenotypic Screening of Offspring

- Following birth, collect tissue samples (e.g., ear notch or blood) from the piglets for genomic DNA extraction.

- Screen for the presence of the transgene using PCR analysis with primers specific to the exogenous gene (e.g., the hDAF minigene) [23]. Confirm integration via Southern blot analysis for more definitive proof of genomic integration.

- For positive founders, assess transgene expression through RT-PCR to detect specific mRNA transcripts and Western blotting or immunohistochemistry to confirm the presence and localization of the expressed protein [23].

Integration with Advanced Genome Editing Technologies

While SMGT is highly effective for introducing transgenes, its potential is magnified when integrated with modern genome editing tools. The emergence of CRISPR/Cas9 and related technologies allows for precise alterations in the pig genome, ranging from target gene knockout (KO) to precise base editing [4] [18]. SMGT can be adapted to deliver not only traditional transgenes but also CRISPR machinery (e.g., Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA) to achieve targeted genetic modifications.

This synergy is particularly powerful for applications like xenotransplantation, where multiplex genetic modifications are required. For instance, the simultaneous knockout of genes encoding for xenoantigens (e.g., GGTA1, CMAH, B4GalNT2) can be combined with the knock-in of human protective genes (e.g., human complement regulatory proteins) to create donor pigs with organs compatible for human transplantation [18]. SMGT provides a viable route for introducing multiple genetic constructs efficiently, as demonstrated by the successful production of multi-gene transgenic pigs using this method [4] [18].

SMGT establishes itself as a cornerstone technology in modern molecular breeding programs, offering a uniquely efficient and accessible pathway for the genetic engineering of pigs. Its demonstrated success in producing stable, multi-transgenic founders, coupled with its potential for integration with precision tools like CRISPR/Cas9, positions SMGT as an indispensable asset for addressing complex challenges in agriculture and biomedicine. The detailed protocols and application notes provided herein serve as a comprehensive guide for researchers aiming to harness this technology. As the field progresses, the continued refinement of SMGT, particularly in enhancing the consistency of DNA uptake and the stability of integration, will further solidify its role in the future of transgenic livestock production.

A Step-by-Step Protocol: Executing SMGT for Pig Transgenesis

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) presents a less technically demanding alternative to methods like somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) for generating genetically modified pigs. This protocol outlines a workflow for producing transgenic offspring using sperm as vectors for exogenous DNA, a technique particularly valuable for biomedical research applications such as xenotransplantation and human disease modeling [18] [24]. The core principle involves introducing a transgene into sperm cells, which subsequently fertilize oocytes to produce genetically modified embryos. This approach can circumvent the need for extensive in vitro manipulation of embryos and the high demand for oocyte donors, which is a significant bottleneck in primate and pig research [24].

The diagram below illustrates the complete SMGT workflow, from sperm preparation to the genotyping of offspring.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and reagents required for the successful implementation of the SMGT protocol.

TABLE 1: Essential Research Reagents for SMGT

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm Source | Acts as the vector for transgene delivery to the oocyte. | Fresh or frozen-thawed porcine sperm [24]. |

| Gene Delivery Vector | Carries the transgene into the sperm cell. | Lentivirus vectors (e.g., carrying EGFP) [24]. |

| Culture Media | Maintains sperm viability during incubation with the transgene. | Standard sperm preparation media. |

| Antibiotics (Optional) | Selects for successfully transfected cells in some protocols. | Puromycin, if vector contains a resistance marker [24]. |

| Primers for PCR | Amplifies specific DNA sequences to detect transgene integration. | Designed for the specific transgene (e.g., EGFP) [24]. |

| Antibodies for Immunofluorescence (IF) | Visualizes transgene-encoded protein expression in cells or tissues. | Anti-GFP antibody to detect EGFP expression [24]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sperm Preparation and Transgene Incubation

This critical first step involves preparing competent sperm cells and loading them with the foreign genetic material.

- Sperm Collection and Washing: Collect semen from a male boar. Dilute the semen in a pre-warmed appropriate buffer (e.g., Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline - DPBS). Centrifuge at 800 x g for 10 minutes to pellet the sperm cells. Remove the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in fresh buffer. Repeat this wash step twice to remove seminal plasma and debris [24].

- Sperm Incubation with Transgene: Resuspend the final sperm pellet in a suitable medium. Add the gene delivery vector (e.g., lentivirus at a titer of ~1.0 × 10^9 TU/mL) to the sperm suspension. A common ratio is 50 µL of concentrated virus diluted to 1 mL with saline [24].

- Incubation Parameters: Incubate the mixture for a predetermined period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) at 37°C to allow for the association of the vector with the sperm cells.

Fertilization and Embryo Transfer

The method of fertilization can be adapted based on laboratory capabilities and regulatory approvals.

- Fertilization Route:

- In Vivo Fertilization (Direct Sperm Transfer): Use the transfected sperm for artificial insemination of a synchronized female pig.

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Co-incubate the transfected sperm with in vitro-matured porcine oocytes. Following fertilization, culture the resulting embryos to a suitable stage (e.g., 2-4 cell stage or blastocyst) [24].

- Embryo Transfer: Surgically transfer the developed embryos into the reproductive tract of a synchronized surrogate sow. The number of embryos transferred depends on the developmental stage and standard practices in porcine embryology [18].

Validation and Genotyping of Offspring

After the birth of offspring, confirm the successful integration and expression of the transgene.

- Tissue Sample Collection: Collect tissue samples (e.g., ear notch, blood) from the piglets for DNA analysis.

- DNA Extraction and PCR: Extract genomic DNA from the samples. Perform Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) using primers specific to the transgene (e.g., EGFP) to confirm its presence in the genome [24].

- Protein Expression Analysis:

- Immunofluorescence (IF): On tissue sections (e.g., testis biopsies), use an antibody against the transgene-encoded protein (e.g., anti-GFP). Fix tissues in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA), embed in paraffin, section, and perform standard IF staining to visualize protein expression [24].

- Flow Cytometry: For cells in suspension, such as sperm or blood cells, analyze for fluorescence (if using a reporter like EGFP) or stain with specific antibodies for analysis by flow cytometry.

- Functional Sperm Analysis (For Founder Males): For male offspring, assess the functionality and transgene carriage of their sperm.

- Sperm Motility and Integrity: Evaluate sperm motility, acrosomal integrity, and mitochondrial membrane potential to ensure the genetic modification does not adversely affect sperm function. Studies show transgenic sperm can have similar freezing and recovery rates to wild-type sperm [24].

- Transmission to F1 Generation: Breed the transgenic founder males to wild-type females to confirm germline transmission and generate heterozygous F1 offspring, thereby establishing a stable transgenic line [24].

Quantitative Data and Analysis

The table below summarizes key parameters for validating successful transgenic offspring.

TABLE 2: Key Validation Parameters for Transgenic Offspring

| Analysis Method | Parameter Measured | Expected Outcome in Positive Founders |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | Presence of transgene DNA in genome | Amplification of a DNA fragment of expected size. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Transgene copy number | Quantification of integrated transgene copies relative to a reference gene. |

| Immunofluorescence (IF) | Spatial expression of transgene protein | Detection of specific fluorescence signal in target tissues/cells. |

| Western Blot | Expression level of transgene protein | Presence of a protein band at the expected molecular weight. |

| Sperm Motility Analysis | Sperm functionality post-modification | Motility rates comparable to wild-type sperm [24]. |

| Histology | Tissue morphology and development | Normal tissue architecture in testis and other organs [24]. |

In the specialized field of transgenic pig production via sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT), the initial processing of semen is a critical determinant of experimental success. The removal of seminal plasma (SP) and the subsequent washing of spermatozoa are not merely preparatory steps but are foundational procedures that significantly influence the efficiency of exogenous DNA uptake, the viability of sperm during preservation, and ultimately, the rate of transgenesis. This protocol details the rationale and methods for seminal plasma removal, framed within the context of an optimized SMGT workflow for pig models. Evidence from recent studies indicates that the deliberate removal of seminal plasma prior to liquid storage of boar spermatozoa enhances their fertilizing ability, leading to higher fertility rates and a greater number of implanted embryos [25]. Furthermore, the presence of seminal plasma during storage can modulate the sperm's ability to undergo crucial processes like capacitation and acrosomal exocytosis, which are vital for successful fertilization post-genetic modification [26]. This document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols to ensure reproducibility and high yield in SMGT experiments.

The Rationale: Why Remove Seminal Plasma?

Seminal plasma, a complex mixture of secretions from the male accessory glands, plays a paradoxical role in assisted reproductive technologies. While it is essential for sperm function in vivo, its prolonged presence in vitro can be detrimental.

- Elimination of Decapacitation Factors: SP contains factors that stabilize the sperm membrane and prevent premature capacitation. While beneficial in the male reproductive tract, these factors can hinder essential processes for SMGT, such as the sperm's responsiveness to in vitro capacitation and its ability to bind and internalize exogenous DNA [25] [27]. Their removal is therefore a strategic step to "prime" the sperm for genetic manipulation.

- Reduction of Oxidative Stress: Semen contains dead spermatozoa, leukocytes, and cellular debris that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS induce oxidative stress, leading to sperm DNA fragmentation, lipid peroxidation of the plasma membrane, and loss of motility [27] [28]. Washing sperm removes these contaminants, thereby preserving sperm genomic integrity and functional competence—a non-negotiable prerequisite for producing viable transgenic embryos.

- Improved Sperm Preservation: For medium-term liquid storage of sperm, which is often required in SMGT protocols, the removal of SP has been shown to be beneficial. Studies in boars demonstrate that sperm stored in the absence of SP for 72 hours present greater resistance to acrosomal damage and maintain higher viability [25]. This improved preservation directly translates to better reproductive performance, as evidenced by significantly higher fertility rates and numbers of implanted embryos in gilts inseminated with SP-free sperm doses [25].

- Facilitation of Exogenous DNA Uptake: In SMGT, spermatozoa act as vectors for foreign DNA. The presence of SP can interfere with the binding and internalization of this DNA. Washing sperm free of SP is thus a critical first step in ensuring efficient gene transfer, a practice successfully employed in the production of hDAF transgenic pigs where SP removal was a key part of the protocol [23].

Table 1: Impact of Seminal Plasma Removal on Sperm Quality and Function

| Parameter | Effect of Seminal Plasma Removal | Significance for SMGT |

|---|---|---|

| Acrosome Integrity | Significantly higher after 72h storage [25] | Better sperm function and oocyte penetration. |

| In Vivo Fertility | Higher fertility rate (63.27% vs 38.57%) and number of implanted embryos (13.71 vs 7.16) [25] | Increased efficiency in generating transgenic offspring. |

| Responsiveness to Capacitation | Maintained or improved [25] [26] | Prepares sperm for fertilization and potentially for DNA uptake. |

| Oxidative Damage | Reduced by removing sources of ROS [27] | Protects sperm DNA integrity, crucial for accurate transgenesis. |

The following table consolidates key quantitative findings from relevant studies on seminal plasma removal, providing a solid evidence base for protocol development.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Seminal Plasma Removal in Different Species and Preservation Conditions

| Species | Storage Condition | Key Findings with SP Removal | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boar | Liquid storage (17°C, 72h) | - Lower acrosome damage (12.87% vs 16.38%)- Higher fertility rate (63.27% vs 38.57%)- More implanted embryos (13.71 vs 7.16) | [25] |

| Boar | Liquid storage (17°C, 48-72h) | Reduced sperm ability to undergo in vitro capacitation and acrosomal exocytosis, involving Ca2+ and Tyr phosphorylation of GSK3α/β. | [26] |

| Ram (Epididymal) | Cooling (5°C, 48h) | Better sperm motility, viability, and mitochondrial activity when stored without SP. Final SP supplementation was beneficial. | [29] |

| Ram (Ejaculated) | Cooling (5°C, 48h) | SP withdrawal impaired sperm function (increased apoptosis, decreased mitochondrial activity). Final SP supplementation was beneficial. | [29] |

| Human (IUI) | Preparation for Insemination | Sperm washing followed by swim-up or density gradient increased motility and normal morphology rates post-processing. | [30] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Sperm Washing by Centrifugation for SMGT

This is a fundamental method for efficiently removing seminal plasma and concentrating spermatozoa, suitable as an initial step in SMGT workflows [23] [28].

Key Reagents:

- Collection Buffer: Swine Fertilization Medium (SFM) or Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS).

- Supplement: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, 6 mg/mL) or synthetic serum substitute.

Detailed Methodology:

- Semen Collection and Dilution: Collect boar semen via the gloved-hand technique. Dilute the raw semen (sperm-rich fraction is preferred) with pre-warmed (37°C) SFM/BSA buffer at a ratio of 1:2 (semen:buffer) [23].

- First Centrifugation: Transfer the diluted semen to a 50 mL conical tube. Centrifuge at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 25°C [23].

- Supernatant Removal: Carefully aspirate and discard the supernatant, which contains the seminal plasma and diluted constituents.

- Second Centrifugation: Resuspend the resulting sperm pellet in fresh SFM/BSA buffer. Centrifuge again at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 17°C [23].

- Final Resuspension: Discard the supernatant and resuspend the final cleaned sperm pellet in an appropriate volume of extender (e.g., Beltsville Thawing Solution - BTS) for liquid storage, or in DNA uptake medium for immediate use in SMGT.

- Quality Assessment: Count sperm concentration using a hemocytometer and assess motility and viability post-wash.

Protocol 2: Sperm Washing Followed by DNA Incubation for SMGT

This protocol, adapted from successful transgenic pig production studies, integrates the washing step directly with the initial phase of gene transfer [23].

Key Reagents:

- As in Protocol 1, plus linearized plasmid DNA (e.g., 0.4 μg per 10^6 sperm).

Detailed Methodology:

- Sperm Washing: Perform steps 1-4 from Protocol 1 to obtain a washed sperm pellet free of seminal plasma.

- Sperm Counting: Resuspend the pellet in SFM/BSA and perform an accurate sperm count.

- DNA Incubation: Dilute the washed sperm cells to a concentration of ~1-1.5 × 10^9 sperm in a total volume of 120 mL SFM/BSA. Add the linearized plasmid DNA and incubate for 2 hours at 17°C. Invert the flask gently every 20 minutes to prevent sedimentation [23].