Signaling Pathway Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy: A Comparative Analysis of Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of signaling pathway inhibitors for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Signaling Pathway Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy: A Comparative Analysis of Efficacy, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of signaling pathway inhibitors for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational science behind major targeted pathways, including BTK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, JAK/STAT, and MAPK, examining their roles in oncogenesis and therapeutic targeting. The content delves into methodological approaches for inhibitor development, from single-target agents to emerging multi-target strategies, and addresses critical challenges including drug resistance, toxicity management, and biomarker-driven patient stratification. Through systematic comparison of inhibitor classes, clinical trial data, and validation frameworks, this review synthesizes key insights to guide future research directions and clinical translation of targeted cancer therapies.

Cellular Signaling Pathways in Oncogenesis: From Basic Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targets

Dysregulation of intracellular signaling pathways is a hallmark of cancer, driving uncontrolled cell proliferation, survival, and metastasis. Four key pathways—BTK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, JAK/STAT, and MAPK—represent critical therapeutic targets in oncology drug development. These pathways function as central communication networks that transduce extracellular signals into cellular responses, regulating fundamental processes including growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. Oncogenic activation of these pathways occurs through various mechanisms including gain-of-function mutations, gene amplifications, and epigenetic alterations. Understanding the comparative architecture, regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic targeting of these pathways provides crucial insights for developing more effective cancer treatments and overcoming drug resistance.

The development of targeted inhibitors against these pathways has revolutionized cancer therapy, moving treatment beyond traditional chemotherapy toward precision medicine approaches. Small molecule inhibitors targeting key nodes within these signaling networks have demonstrated significant clinical efficacy across diverse hematological malignancies and solid tumors. This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of BTK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, JAK/STAT, and MAPK pathway inhibitors, focusing on their mechanisms of action, clinical applications, and experimental evaluation methodologies to inform research and drug development efforts.

BTK Signaling Pathway and Inhibitors

Pathway Biology and Clinical Significance

Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase belonging to the Tec family of kinases that plays an essential role in B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, development, and differentiation [1] [2]. Following BCR stimulation, BTK becomes phosphorylated and activates downstream signaling cascades that promote B-cell proliferation, survival, and metabolic adaptation [2]. The crucial role of BTK in normal B-cell development is highlighted by X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), a primary immunodeficiency disorder caused by mutations in the BTK gene that result in almost no production of mature B cells and premature cell death [1] [2].

In malignant B-cells, BTK mediates proliferative and pro-survival signals through impaired adhesion properties and interaction with the tumor microenvironment [2]. This central role in B-cell malignancies has made BTK an attractive therapeutic target, particularly for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), and Waldenström macroglobulinemia [1]. BTK inhibitors have dramatically changed the treatment landscape for these malignancies, demonstrating significant improvement in progression-free survival and overall survival compared with traditionally used chemoimmunotherapy [1].

Key BTK Inhibitors and Clinical Applications

Ibrutinib, the first-in-class BTK inhibitor, received FDA approval in 2013 for MCL and subsequently in 2014 for CLL, revolutionizing treatment for B-cell malignancies [1] [2]. Ibrutinib covalently and irreversibly binds to the cysteine-481 (C481) residue in the ATP-binding domain of BTK, blocking its ability to phosphorylate substrates and suppressing downstream survival signaling [1]. The RESONATE phase III trial established ibrutinib's efficacy in relapsed/refractory CLL, demonstrating significantly improved progression-free survival (HR = 0.22) and overall survival (HR = 0.43) compared to ofatumumab [1]. Long-term follow-up data confirmed durable responses, with 5-year PFS rates of 70% in previously untreated older CLL patients [1].

Next-generation BTK inhibitors including acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib were developed with enhanced selectivity for BTK to minimize off-target effects associated with ibrutinib [1] [2]. These agents show similar efficacy to ibrutinib but with improved safety profiles, particularly regarding cardiovascular toxicities [2]. Acalabrutinib received FDA approval in 2017 for MCL and later for CLL, while zanubrutinib was approved in 2019 for MCL [1]. Emerging non-covalent BTK inhibitors such as pirtobrutinib represent a promising approach to overcome resistance mediated by C481 mutations through reversible binding at alternative sites [1].

Table 1: Clinically Approved BTK Inhibitors in Oncology

| Inhibitor | Year Approved | Primary Indications | Key Clinical Trial Data | Major Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibrutinib | 2013 (MCL), 2014 (CLL) | CLL, SLL, MCL, WM, MZL, cGVHD | RESONATE: PFS HR=0.22 vs ofatumumab; 5-year PFS 70% in frontline CLL | Atrial fibrillation, bleeding, rash, diarrhea, infections |

| Acalabrutinib | 2017 | CLL, SLL, MCL | ELEVATE-TN: Superior PFS vs chlorambucil+obinutuzumab | Headache, diarrhea, musculoskeletal pain |

| Zanubrutinib | 2019 | MCL, WM | ASPEN: Similar overall response to ibrutinib in WM with improved safety | Neutropenia, upper respiratory infections |

| Tirabrutinib | 2020 (Japan) | Primary CNS lymphoma | - | Rash, neutropenia, lymphopenia |

Resistance Mechanisms and Novel Approaches

Despite the efficacy of BTK inhibitors, approximately 60% of patients treated long-term with covalent BTK inhibitors develop resistance [2]. The most common mechanism involves a cysteine-to-serine substitution at position 481 (C481S) in BTK, which prevents covalent binding of irreversible inhibitors [2]. Additional resistance mechanisms include mutations in downstream signaling molecules such as PLCγ2 and activation of alternative survival pathways [1]. To address these resistance mechanisms, non-covalent BTK inhibitors such as fenebrutinib and ARQ 531 are under investigation and have demonstrated efficacy against C481 mutant clones [2].

Current research focuses on combination therapies that target multiple pathways simultaneously. Clinical trials are exploring BTK inhibitors combined with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (e.g., rituximab, obinutuzumab) or BCL2 inhibitors (e.g., venetoclax) to enhance therapeutic efficacy and potentially achieve treatment-free remission [1] [2]. The synergistic effect of these combinations may address the heterogeneity of B-cell malignancies and reduce the emergence of resistant subclones.

PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway and Inhibitors

Pathway Architecture and Oncogenic Activation

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR (PAM) signaling pathway represents a highly conserved signal transduction network that regulates cell survival, growth, proliferation, and metabolism in response to extracellular stimuli [3]. Growth factor binding to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) or G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) initiates the canonical pathway, leading to activation of class I PI3K which phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) [4] [3]. PIP3 serves as a docking site for Akt and PDK1, leading to Akt phosphorylation and activation. Activated Akt then modulates numerous downstream substrates including mTOR, a master regulator of cell growth and metabolism [3].

The PAM pathway is the most frequently activated signaling pathway in human cancer, with aberrations occurring in approximately 50% of tumors [3]. Oncogenic activation occurs through multiple mechanisms including RTK overactivation, PI3K catalytic subunit (PIK3CA) mutations or amplification, loss of the tumor suppressor PTEN (which dephosphorylates PIP3), and Akt gain-of-function mutations [4] [3]. PIK3CA is the most commonly mutated oncogene across tumor lineages, with hotspot mutations E545K and H1047R driving constitutive pathway activation [3]. The central role of PAM signaling in cancer has made it a prime target for therapeutic intervention.

Table 2: PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway Inhibitors and Their Applications

| Inhibitor Class | Target Specificity | Representative Agents | Key Indications | Major Resistance Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-PI3K inhibitors | All class I PI3K isoforms | Buparlisib, Copanlisib | Breast cancer, lymphoma | RTK feedback activation, PIK3CA mutations |

| Isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors | Specific PI3K isoforms | Alpelisib (p110α), Idelalisib (p110δ) | PIK3CA-mutated breast cancer, CLL | AKT reactivation, additional PIK3CA mutations |

| AKT inhibitors | All AKT isoforms | Ipatasertib, Capivasertib | AKT1-mutated cancers, TNBC | Upstream RTK activation, mTOR feedback |

| mTORC1 inhibitors | mTORC1 complex | Everolimus, Temsirolimus | RCC, breast cancer, NET | mTORC2-mediated AKT activation |

| Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors | PI3K and mTORC1/2 | Dactolisib, Voxtalisib | Various solid tumors | Compensatory pathway activation |

Therapeutic Targeting and Clinical Applications

PI3K pathway inhibitors are categorized based on their specific molecular targets along the signaling cascade [4]. First-generation inhibitors include rapamycin analogs (rapalogs) such as everolimus and temsirolimus that specifically target mTORC1 [4] [3]. These agents demonstrated clinical efficacy in renal cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and hormone receptor-positive breast cancer but have limited activity in other malignancies due to feedback activation of upstream signaling [3]. More recent development has focused on ATP-competitive inhibitors that target both mTORC1 and mTORC2, pan-PI3K inhibitors that inhibit all four class I PI3K isoforms, and isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors [4].

Isoform-selective inhibitors offer the potential for targeted therapy with reduced toxicity. Idelalisib, a p110δ inhibitor, received approval for relapsed CLL and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, exploiting the predominantly hematopoietic expression of p110δ [3]. Alpelisib, a p110α-specific inhibitor, is approved for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer in combination with endocrine therapy [3]. AKT inhibitors such as capivasertib and ipatasertib have shown promise in clinical trials, particularly in tumors with AKT alterations and triple-negative breast cancer [3].

Experimental Approaches for PI3K Pathway Inhibition

Research continues to address the challenges of therapeutic resistance and toxicity associated with PAM pathway inhibition. Combination strategies targeting parallel or compensatory pathways are under active investigation, including PI3K inhibitors with MEK inhibitors, CDK4/6 inhibitors, or endocrine therapies [3]. Novel therapeutic approaches include PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) that degrade target proteins, and adaptive dosing schedules to manage toxicities while maintaining efficacy [3].

The central role of PI3K signaling in immunology has also prompted investigation of PI3K inhibitors in immuno-oncology combinations. Preclinical models demonstrate that PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ inhibition can enhance antitumor immunity by modulating regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, respectively [3]. Clinical trials are evaluating these combinations to overcome resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway and Inhibitors

Pathway Components and Regulatory Mechanisms

The Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway serves as a primary signaling cascade for numerous cytokines, interferons, growth factors, and hormones [5]. This pathway consists of three main components: ligand-receptor complexes, JAK kinases (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2), and STAT transcription factors (STAT1-6) [6] [5]. Upon ligand binding, receptor-associated JAKs undergo trans-phosphorylation and subsequently phosphorylate STAT proteins. Phosphorylated STATs dimerize and translocate to the nucleus where they regulate transcription of target genes involved in proliferation, inflammation, and immune response [5].

The JAK family proteins contain seven homology domains (JH1-JH7), with JH1 representing the kinase domain and JH2 serving as a pseudokinase domain that regulates kinase activity [6] [5]. JAK3 is primarily expressed in hematopoietic cells and requires the common gamma chain (γc) for signaling, while other JAK family members are more widely expressed [5]. STAT proteins contain SH2 domains that facilitate their recruitment to phosphorylated receptor motifs and mediate dimerization [5]. The JAK/STAT pathway is tightly regulated by multiple mechanisms including suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins, protein inhibitors of activated STATs (PIAS), and protein tyrosine phosphatases [5].

JAK Inhibitors in Clinical Practice

JAK inhibitors are classified into first-generation non-selective inhibitors and second-generation more selective agents [6]. First-generation inhibitors such as tofacitinib and baricitinib inhibit multiple JAK family members and are approved for autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis [6] [7]. Second-generation inhibitors including filgotinib (JAK1-selective) and upadacitinib (JAK1-selective) offer improved specificity to minimize off-target effects [6].

In oncology, ruxolitinib (a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor) is approved for myelofibrosis and polycythemia vera, representing the primary application of JAK inhibitors in hematologic malignancies [6] [5]. Ruxolitinib demonstrates efficacy in reducing splenomegaly and constitutional symptoms in myeloproliferative neoplasms, particularly those driven by the JAK2V617F mutation [6]. Fedratinib, a more selective JAK2 inhibitor, is also approved for myelofibrosis [6]. The development of JAK inhibitors for solid tumors has been more challenging due to pathway complexity and toxicities.

Classification and Binding Mechanisms

JAK inhibitors can be categorized based on their binding mechanisms as reversible (competitive) or irreversible (covalent) inhibitors [6]. Reversible inhibitors include type I inhibitors that bind to the active kinase conformation and compete with ATP, and type II inhibitors that bind to the inactive conformation [6]. Most clinically approved JAK inhibitors are type I ATP-competitive inhibitors. Irreversible JAK inhibitors typically target the unique cysteine residue (Cys909) in JAK3 and form covalent bonds, enhancing selectivity [6]. Ritlecitinib represents an example of an irreversible JAK3 inhibitor currently in clinical development [6].

JAK inhibitors are further characterized by their kinase inhibition profiles, which determine their therapeutic applications and safety considerations. The relative inhibition of different JAK isoforms influences both efficacy and toxicity profiles, with JAK1 inhibition primarily mediating anti-inflammatory effects, JAK2 inhibition associated with hematologic toxicities, and JAK3 inhibition providing more specific immunomodulation [6] [5].

MAPK Signaling Pathway and Inhibitors

Cascade Architecture and Oncogenic Roles

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways represent ubiquitous intracellular signaling networks that regulate diverse cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and stress responses [8]. Four major MAPK family members have been characterized: extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), p38 MAP kinases, and ERK5 [8] [9]. Each MAPK is activated through a three-tiered kinase cascade consisting of MAPK kinase kinases (MAP3Ks) that phosphorylate and activate MAPK kinases (MAP2Ks), which in turn phosphorylate and activate the MAPKs [8].

The ERK1/2 pathway (Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK) is the most extensively studied MAPK cascade and is frequently activated in cancer through mutations in upstream regulators including Ras (KRAS, NRAS) and Raf (BRAF) [8] [9]. This pathway transduces signals from growth factor receptors to regulate gene expression and cell cycle progression. The JNK and p38 pathways primarily respond to cellular stress and inflammatory cytokines, while ERK5 integrates signals from growth factors and stress stimuli [8]. Constitutive activation of MAPK pathways, particularly ERK1/2, has been implicated in the initiation and progression of various cancers, making these pathways attractive therapeutic targets [8].

Targeted Inhibitors in Clinical Use

The development of MAPK pathway inhibitors has progressed significantly, with multiple agents receiving FDA approval [8] [9]. BRAF inhibitors such as vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib are approved for BRAF-mutant melanoma, often in combination with MEK inhibitors to enhance efficacy and prevent resistance [9]. MEK inhibitors (trametinib, cobimetinib, binimetinib) target the downstream kinases MEK1/2 and are used in combination with BRAF inhibitors for BRAF-mutant melanoma and as monotherapy in other malignancies [8] [9].

p38 MAPK inhibitors including SB203580 and BIRB-796 were developed primarily for inflammatory diseases rather than oncology applications [8] [9]. Similarly, JNK inhibitors have faced challenges in clinical development due to toxicity concerns and limited efficacy [8]. The ERK1/2 pathway inhibitors targeting receptor tyrosine kinases upstream of MAPK signaling include gefitinib and erlotinib (EGFR inhibitors), sunitinib (PDGFR, VEGFR, c-Kit inhibitor), and sorafenib (multi-kinase inhibitor) [8].

Table 3: Clinically Utilized MAPK Pathway Inhibitors

| Therapeutic Target | Inhibitor | Primary Indications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF | Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib, Encorafenib | BRAF-mutant melanoma | Resistance development, paradoxical activation in wild-type BRAF |

| MEK1/2 | Trametinib, Cobimetinib, Binimetinib | BRAF-mutant melanoma (with BRAF inhibitors), NSCLC | Ocular toxicities, skin rash, diarrhea |

| EGFR | Gefitinib, Erlotinib | EGFR-mutant NSCLC | Resistance mutations (T790M, C797S) |

| Multi-targeted RTK | Sorafenib, Sunitinib | RCC, HCC, GIST | Broad toxicity profile, off-target effects |

| p38 | SB203580, BIRB-796 | Inflammatory diseases (investigational) | Limited efficacy in clinical trials |

Research Tools and Experimental Applications

MAPK pathway inhibitors serve as valuable research tools for elucidating pathway functions and validating therapeutic targets [8]. Selective inhibitors including U0126 and PD0325901 (MEK1/2 inhibitors), SB203580 (p38 inhibitor), and SP600125 (JNK inhibitor) have been extensively used to dissect the contributions of specific MAPK pathways to cellular responses [8]. These compounds enable researchers to establish causal relationships between pathway activation and biological outcomes through pharmacological inhibition.

Methodologies for evaluating MAPK pathway inhibition typically involve immunoblotting with phosphorylation-state-specific antibodies to quantify changes in pathway activation [8]. Standard experimental protocols include serum starvation followed by stimulation with growth factors or cytokines in the presence or absence of inhibitors, with subsequent analysis of phosphorylated MAPK substrates [8]. These approaches allow researchers to assess inhibitor potency, specificity, and duration of action in cellular models.

Comparative Analysis of Pathway Inhibitors

Therapeutic Targeting Strategies Across Pathways

The four signaling pathways discussed employ distinct therapeutic targeting strategies based on their molecular architectures and regulatory mechanisms. BTK inhibitors primarily utilize irreversible covalent binding to achieve sustained target inhibition, leveraging the unique cysteine residue (C481) in BTK's active site [1] [2]. This approach provides prolonged pharmacodynamic effects despite rapid plasma clearance. In contrast, most PI3K/Akt/mTOR, JAK/STAT, and MAPK pathway inhibitors function through reversible, competitive inhibition at ATP-binding sites [6] [4] [3]. The conservation of ATP-binding pockets across kinase families presents challenges for achieving selectivity, which has been addressed through structural biology-guided drug design.

The development of isoform-selective inhibitors represents an important advancement for minimizing off-target toxicities, particularly for the PI3K and JAK families where different isoforms serve distinct physiological functions [6] [3]. Alternative targeting strategies include allosteric inhibitors that bind outside the ATP pocket (e.g., MEK inhibitors), dual inhibitors that simultaneously target multiple pathway components (e.g., PI3K/mTOR inhibitors), and covalent irreversible inhibitors beyond BTK targeting (e.g., JAK3 covalent inhibitors) [6] [8] [4].

Resistance Mechanisms and Combination Approaches

Therapeutic resistance remains a significant challenge across all pathway inhibitors and develops through both shared and pathway-specific mechanisms. Common resistance mechanisms include on-target mutations that impair drug binding (e.g., BTK C481S, EGFR T790M), activation of alternative signaling pathways that bypass inhibition, and feedback loops that reactivate the targeted pathway [1] [2] [3]. The mutation profile varies by pathway, with kinase domain mutations predominating for BTK, EGFR, and ALK inhibitors, while PI3K pathway resistance frequently involves PTEN loss or Akt activation [2] [3].

Combination therapies represent the primary strategy to overcome or prevent resistance. Rational combination approaches include vertical pathway inhibition (targeting multiple nodes within the same pathway), horizontal pathway inhibition (targeting parallel pathways), and integration with non-kinase targeted therapies [1] [3]. Clinical successes include BRAF+MEK inhibitor combinations in melanoma, BTK+BCL2 inhibitor combinations in CLL, and PI3K inhibitor+endocrine therapy in breast cancer [1] [3]. The optimal combination strategies continue to be refined through preclinical models and biomarker-driven clinical trials.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Design

Standardized Assessment of Inhibitor Efficacy

Robust evaluation of signaling pathway inhibitors requires integrated methodological approaches spanning biochemical, cellular, and in vivo models. Standard assessment includes in vitro kinase assays to determine inhibitor potency (IC50 values) and selectivity across kinase panels [8] [9]. Cellular models then evaluate target engagement through immunoblotting of phosphorylated substrates, complemented by functional assays measuring proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle distribution [8].

For immune cell-targeting inhibitors such as BTK and JAK inhibitors, additional functional assays evaluate effects on primary immune cells including B-cell receptor signaling (for BTK inhibitors) or cytokine responses (for JAK inhibitors) [2] [5]. In vivo evaluation typically employs xenograft models for oncology applications and genetically engineered mouse models that recapitulate human diseases [1] [5]. These preclinical models help establish pharmacodynamic biomarkers that can be translated to clinical studies for assessing target inhibition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Signaling Pathway Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phospho-specific antibodies | p-BTK (Y223), p-AKT (S473), p-STAT3 (Y705), p-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204) | Western blot, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry | Validation of specificity, optimization of conditions |

| Selective inhibitors | Ibrutinib (BTK), Alpelisib (PI3Kα), Ruxolitinib (JAK1/2), Trametinib (MEK1/2) | Pathway validation, combination studies | Off-target effects, concentration optimization |

| Recombinant cytokines/growth factors | IL-6, IL-4, B-cell activating factor, EGF | Pathway stimulation assays | Concentration response, timing of stimulation |

| Kinase assay systems | ADP-Glo, mobility shift assays, radioactive filtration assays | Biochemical kinase inhibition profiling | ATP concentration optimization, enzyme linearity |

| Cell line models | Mino, JeKo-1 (MCL), Rec-1 (MCL), Ba/F3 engineered lines | Proliferation, apoptosis, signaling studies | Authentication, mycoplasma testing |

| HMG-CoA Reductase-IN-1 | HMG-CoA Reductase-IN-1, MF:C27H29N3O7, MW:507.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Nlrp3-IN-30 | Nlrp3-IN-30, MF:C19H17F3N4O2, MW:390.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

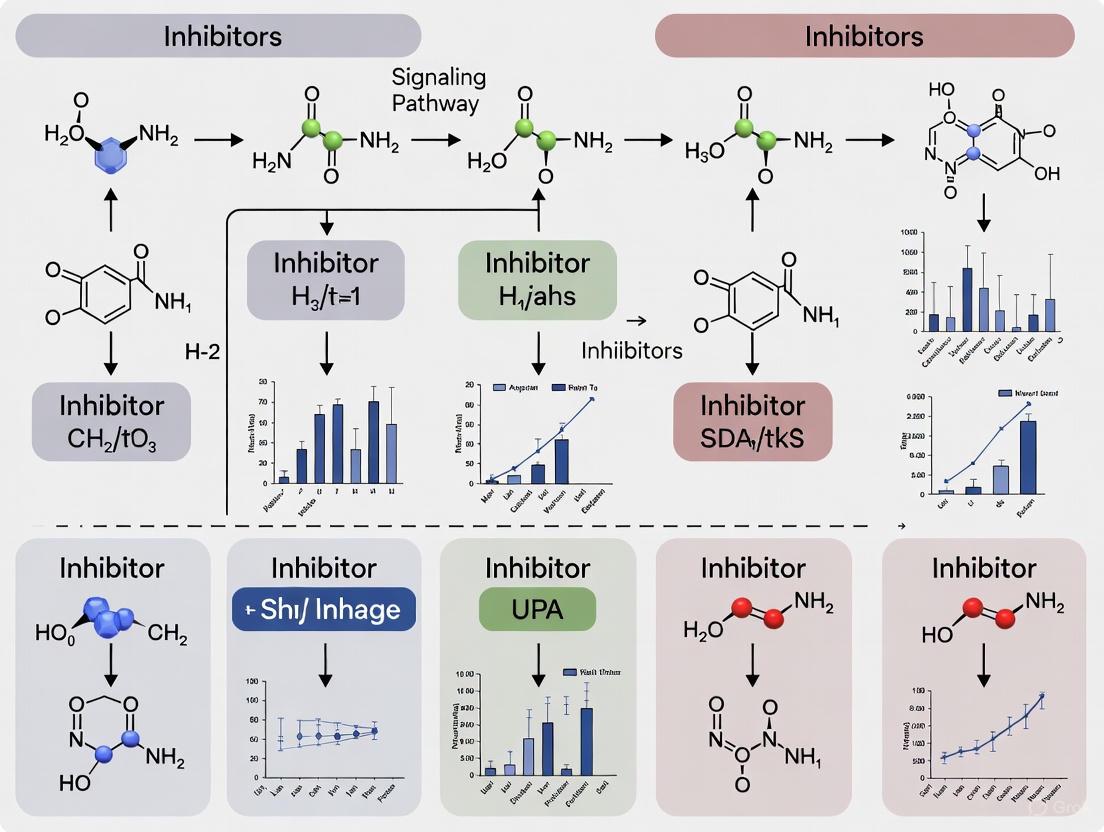

Visualizing Signaling Networks and Experimental Approaches

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental methodologies discussed in this review, created using DOT visualization language.

Diagram 1: BTK Signaling Pathway and Inhibitor Mechanism

Diagram 2: PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway and Inhibition Points

Diagram 3: Experimental Workflow for Pathway Inhibition Studies

The comparative analysis of BTK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, JAK/STAT, and MAPK signaling pathway inhibitors reveals both shared principles and distinct challenges in targeted cancer therapy. While each pathway possesses unique biological functions and therapeutic applications, common themes emerge including the importance of selectivity for minimizing toxicities, the inevitability of resistance mechanisms, and the necessity of rational combination approaches. The continued refinement of these targeted agents depends on deeper understanding of pathway biology, resistance mechanisms, and predictive biomarkers.

Future directions in signaling pathway inhibition include the development of novel therapeutic modalities such as PROTACs that degrade target proteins rather than simply inhibiting them, allosteric inhibitors with improved selectivity profiles, and fourth-generation inhibitors capable of overcoming resistance mutations [2] [3]. Additionally, the integration of pathway inhibitors with immunotherapy represents a promising frontier, particularly for modulating the tumor microenvironment. As our understanding of signaling network complexity grows, so too will our ability to develop more effective, durable, and personalized cancer therapies targeting these fundamental regulatory pathways.

Cancer pathogenesis is driven by a complex interplay of molecular dysregulation mechanisms that enable uncontrolled cell proliferation, evasion of cell death, and metastatic potential. The transition from normal cellular homeostasis to malignant transformation involves three fundamental categories of alterations: genetic mutations that directly change DNA sequence and protein function, gene amplifications that lead to oncogene overexpression, and epigenetic modifications that alter gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence [10] [11]. These mechanisms collectively hijack normal signaling pathways, creating dependencies that can be therapeutically targeted.

The landscape of targeted cancer therapy has evolved substantially from conventional cytotoxic agents to precision medicines that specifically target these molecular vulnerabilities. This evolution began with the recognition that cancers derived from different tissues often share common driver pathways, and that tumors from the same tissue of origin may harbor distinct molecular alterations requiring different therapeutic approaches [10]. The contemporary paradigm of precision medicine leverages detailed molecular profiling to match patients with targeted therapies based on the specific dysregulation mechanisms present in their tumors, moving beyond histology-based classification to mechanism-driven treatment selection [10].

Comparative Analysis of Dysregulation Mechanisms

Genetic Mutations: Direct Alterations of DNA Sequence

Genetic mutations constitute the most fundamental mechanism of oncogenic transformation, directly altering DNA sequence and consequently protein structure and function. These mutations can range from single nucleotide substitutions to large-scale chromosomal rearrangements, with varying impacts on oncogenic signaling. Gain-of-function mutations in proto-oncogenes (e.g., BRAF V600E) and loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressor genes (e.g., TP53) represent two major categories of driver mutations in cancer [10].

The clinical success of mutation-targeted therapies is exemplified by inhibitors targeting the BCR-ABL fusion protein in chronic myelogenous leukemia (imatinib), BRAF V600E mutations in melanoma (vemurafenib), and EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (lazertinib) [10] [7]. These therapies demonstrate the principle of oncogene addiction, whereby cancer cells become dependent on a single activated oncogenic pathway or protein, creating a therapeutic window that can be exploited with targeted agents [10].

Gene Amplifications: Quantitative Increases in Oncogenic Signaling

Gene amplification represents another fundamental mechanism of oncogenic activation, leading to increased copy number and consequent overexpression of oncogenes. This quantitative increase in gene dosage results in enhanced oncogenic signaling without necessarily altering the protein structure itself. A paradigmatic example is HER2/neu (ERBB2) amplification in breast cancer, where increased gene copy number leads to overexpression of the HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase, driving proliferative signaling through multiple downstream pathways [10] [12].

The development of HER2-targeted therapies including trastuzumab, ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1), and trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) has fundamentally transformed the prognosis for HER2-positive breast cancer patients [12]. These therapies demonstrate that quantitative overexpression of oncogenes represents a clinically actionable vulnerability, with antibody-drug conjugates like T-DXd showing particular promise in managing HER2-positive breast cancer brain metastases due to their enhanced CNS penetration [12].

Epigenetic Modifications: Reversible Regulation of Gene Expression

Epigenetic modifications constitute a third major category of oncogenic dysregulation, involving heritable changes in gene expression that do not alter the underlying DNA sequence. The five principal mechanisms of epigenetic regulation include DNA modification, histone modification, RNA modification, chromatin remodeling, and non-coding RNA regulation [13]. These mechanisms function as an integrated regulatory system that controls chromatin state and accessibility, with enzymes categorized as "writers," "erasers," "readers," and "remodelers" based on their functions [13].

Cancer cells frequently exhibit widespread epigenetic alterations including global DNA hypomethylation with localized hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters, aberrant histone modification patterns, and dysregulated expression of non-coding RNAs [13] [11]. These changes can silence tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes, contributing fundamentally to malignant transformation. The reversibility of epigenetic modifications makes them particularly attractive therapeutic targets, as evidenced by FDA-approved agents targeting DNA methyltransferases (azacytidine, decitabine) and histone deacetylases (vorinostat, romidepsin) [13] [10].

Table 1: Comparative Features of Major Dysregulation Mechanisms in Cancer

| Dysregulation Mechanism | Molecular Basis | Key Examples | Therapeutic Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Mutations | Alteration of DNA sequence leading to functional protein changes | BRAF V600E, TP53, IDH1/2, KRAS | Kinase inhibitors, PARP inhibitors (synthetic lethality) |

| Gene Amplifications | Increased gene copy number leading to protein overexpression | HER2/neu, MYC, EGFR | Monoclonal antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| Epigenetic Modifications | Reversible changes to chromatin structure and accessibility | DNMT3A, EZH2, TET2 | DNMT inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying Dysregulation Mechanisms

In Vitro Models for Inhibitor Screening and Validation

In vitro cancer models provide controlled systems for initial evaluation of therapeutic agents targeting specific dysregulation mechanisms. Cell line models enable detailed investigation of inhibitor effects on molecular pathways, with standardized protocols for assessing target engagement, pathway modulation, and cellular responses. The comparative analysis of CK2 inhibitors CX-4945 and SGC-CK2-2 exemplifies a rigorous in vitro approach for evaluating inhibitor specificity and efficacy [14].

Experimental Protocol: Kinase Inhibitor Profiling in Cancer Cell Lines

Cell Culture Conditions: Maintain human cancer cell lines (e.g., HeLa cervical cancer, MDA-MB-231 breast cancer) in appropriate media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in 5% CO₂ [14].

Inhibitor Treatment: Prepare serial dilutions of kinase inhibitors (e.g., CX-4945, SGC-CK2-2) in DMSO, with final concentrations typically ranging from 0.5-20 μM based on preliminary dose-finding studies. Include DMSO-only controls for normalization [14].

Treatment Duration: Expose cells to inhibitors for 24 hours to assess acute effects on signaling pathways, or for extended periods (72-96 hours) to evaluate effects on cell viability and proliferation [14].

Target Engagement Assessment: Harvest cells and prepare protein lysates for Western blot analysis using phosphospecific antibodies against known substrate phosphorylation sites (e.g., pS129-Akt, pS13-Cdc37 for CK2 inhibition) [14].

Validation of Specificity: Utilize phosphoantibodies recognizing consensus motif sequences (e.g., pS/pT-D-X-E for CK2 substrates) to evaluate global inhibition of target kinase activity and detect potential off-target effects [14].

Functional Assays: Assess cell viability using MTT, MTS, or CellTiter-Glo assays following 72-hour inhibitor treatment to correlate pathway inhibition with functional consequences [14].

This experimental approach enables systematic comparison of inhibitor potency (IC50 determination) and specificity across multiple cell line models, providing critical data for lead optimization and mechanism of action studies.

In Vivo Models for Therapeutic Efficacy Assessment

In vivo models provide essential preclinical data on the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and therapeutic efficacy of targeted agents in physiologically relevant contexts. These models capture the complexity of tumor microenvironment interactions, drug metabolism, and host toxicity that cannot be fully recapitulated in vitro.

Experimental Protocol: Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Therapeutic Studies

Model Establishment: Implant patient-derived tumor fragments or cell suspensions subcutaneously into immunocompromised mice (e.g., NSG mice) to establish PDX models that maintain the molecular characteristics of original tumors [10].

Treatment Initiation: Randomize mice into treatment groups when tumors reach approximately 100-200 mm³, ensuring balanced group assignment based on initial tumor volume [15].

Dosing Regimens: Administer therapeutic agents via appropriate routes (oral gavage for small molecules, intraperitoneal or intravenous injection for biologics) at established maximum tolerated doses or clinically relevant concentrations [15].

Efficacy Monitoring: Measure tumor dimensions 2-3 times weekly using calipers, calculating volume using the formula: V = (length × width²)/2. Monitor body weight as an indicator of treatment toxicity [15].

Endpoint Analysis: Harvest tumors at study endpoint for molecular profiling (Western blot, IHC, RNA-seq) to confirm target modulation and identify potential resistance mechanisms [15].

PDX models have become the gold standard for preclinical therapeutic evaluation due to their preservation of tumor heterogeneity and predictive value for clinical response [10].

Signaling Pathways Commonly Dysregulated in Cancer

Multiple signaling pathways are frequently dysregulated in cancer through mutations, amplifications, or epigenetic mechanisms. Understanding these pathways is essential for developing effective targeted therapies and combination strategies.

Diagram 1: Key Oncogenic Signaling Pathways. This diagram illustrates major signaling pathways frequently dysregulated in cancer through mutations, amplifications, or epigenetic alterations, highlighting potential therapeutic targeting opportunities.

Comparative Efficacy of Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Different Dysregulation Mechanisms

Therapeutic approaches vary significantly based on the specific dysregulation mechanism being targeted. The tables below summarize comparative efficacy data for agents targeting different categories of molecular alterations.

Table 2: Comparative Efficacy of Agents Targeting Genetic Mutations and Amplifications

| Therapeutic Class | Specific Agent | Molecular Target | Cancer Type | Efficacy Metrics | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors | Lazertinib | EGFR mutation | NSCLC | PFS: 20.6 months | Third-generation EGFR TKI [7] |

| BRAF Inhibitors | Vemurafenib | BRAF V600E | Melanoma | Response Rate: 48% | Single-agent therapy [10] |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates | Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (T-DXd) | HER2 amplification | Breast Cancer (BCBM) | CNS Progression: HR 0.17 (vs. physician's choice) | HER2-positive with brain metastases [12] |

| CK2 Inhibitors | CX-4945 | CK2 kinase | Various cancers | pS129-Akt IC50: 0.7-0.9 μM | In vitro potency [14] |

| CK2 Inhibitors | SGC-CK2-2 | CK2 kinase | Various cancers | pS129-Akt IC50: 1.3-2.2 μM | Improved specificity, reduced potency [14] |

Table 3: Comparative Efficacy of Agents Targeting Epigenetic Modifications

| Therapeutic Class | Specific Agent | Molecular Target | Cancer Type | Efficacy Metrics | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | Azacytidine | DNA methyltransferases | MDS, AML | Overall Response: ~15-20% | Hematologic malignancies [10] |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Vorinostat | Histone deacetylases | CTCL | Response Rate: ~30% | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [10] |

| EZH2 Inhibitors | Tazemetostat | EZH2 | Lymphoma | Response Rate: 69% (EZH2 mutant) | Relapsed/refractory lymphoma [10] |

| IDH Inhibitors | AG-120 (Ivosidenib) | IDH1 mutation | AML | Complete Response: 30.4% | IDH1-mutant AML [10] |

Table 4: Comparative Efficacy of Androgen Receptor Pathway Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer

| Therapeutic Agent | Molecular Target | Patient Population | 2-Year PFS to mCRPC | PSA ≤0.2 ng/mL (12 weeks) | Time to PSA Nadir (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abiraterone acetate | Androgen synthesis | mHSPC (n=94) | 74.1% | 25.5% | 12.2 |

| Apalutamide | Androgen receptor | mHSPC (n=91) | 81.4% | 44.0% | 7.2 |

| Enzalutamide | Androgen receptor | mHSPC (n=34) | 85.6% | 55.9% | 7.5 |

Data adapted from real-world comparative effectiveness study of ARPIs in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) [16]

Advanced Research Tools and Computational Approaches

Modern cancer research utilizes sophisticated computational approaches to identify synergistic drug combinations and optimize therapeutic strategies. Artificial intelligence and multi-omics integration have transformed drug discovery by enabling prediction of drug interactions and patient-specific therapeutic responses [17].

Diagram 2: Computational Framework for Drug Combination Prediction. This workflow illustrates the integration of multi-omics data through AI approaches to predict synergistic drug combinations and identify predictive biomarkers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Dysregulation Mechanisms

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Inhibitors | CX-4945 (Silmitasertib), SGC-CK2-2 | Target validation, signaling pathway analysis | CX-4945: Broad kinase inhibition; SGC-CK2-2: Enhanced specificity [14] |

| Epigenetic Modulators | Azacytidine, Vorinostat, Tazemetostat | Epigenetic mechanism studies, combination therapy | DNMT inhibition, HDAC inhibition, EZH2 inhibition [13] [10] |

| Phosphospecific Antibodies | pS129-Akt, pS13-Cdc37, pS/pT-D-X-E motif | Target engagement assessment, pathway modulation | Validation in knockout cells, motif-specific recognition [14] |

| Computational Platforms | DeepSynergy, AuDNNsynergy, DrugComboRanker | Drug combination prediction, multi-omics integration | Deep learning architectures, network analysis capabilities [17] |

| Cell Line Models | HeLa, MDA-MB-231, Patient-derived organoids | High-throughput screening, mechanism studies | Well-characterized genetic backgrounds, disease representation [14] |

| Akt-IN-21 | Akt-IN-21, MF:C26H34N2O4, MW:438.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Gli1-IN-1 | Gli1-IN-1|GLI1 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Gli1-IN-1 is a potent GLI1 inhibitor for cancer research. It targets Hedgehog signaling. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The comparative analysis of dysregulation mechanisms in cancer reveals an increasingly sophisticated understanding of oncogenic processes and their therapeutic vulnerabilities. Genetic mutations, amplifications, and epigenetic alterations represent distinct but interconnected mechanisms that can be selectively targeted with specific therapeutic classes. The emerging paradigm in oncology emphasizes mechanism-driven therapy selection based on the specific molecular alterations present in individual tumors, rather than histology alone.

Future progress in cancer therapeutics will likely involve rational combination strategies that simultaneously target multiple dysregulation mechanisms, such as combining epigenetic modifiers with kinase inhibitors or immunotherapy agents. The integration of computational approaches with experimental validation will accelerate the identification of synergistic drug combinations and biomarkers of response. As our understanding of cancer dysregulation mechanisms deepens, so too will our ability to develop precisely targeted, effective therapeutic strategies that improve outcomes for cancer patients across diverse malignancy types.

Growth factor receptors are membrane-bound enzyme-linked receptors that play a pivotal role in cellular signaling, regulating critical processes including proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, and apoptosis [18]. The majority of these receptors are receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which undergo ligand-induced activation and initiate downstream signaling cascades [19] [18]. Understanding the structure-function relationships of these receptors and their effectors is fundamental to developing targeted cancer therapies, as dysregulated signaling drives tumor progression, angiogenesis, and metastasis [20] [19] [21]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major growth factor receptor families, their structural features, and the efficacy of therapeutic inhibitors, framing this within ongoing research on signaling pathway inhibition.

Structural Classification and Activation Mechanisms

Growth factor receptors share a common molecular organization but exhibit distinct structural features that define their activation mechanisms and functional roles [22].

Common Structural Domains

All RTKs contain three fundamental domains: an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain [18]. Ligand binding to the extracellular domain induces receptor dimerization or oligomerization, facilitating trans-autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues within the cytoplasmic domain [19] [18]. This phosphorylation stabilizes the active receptor conformation and creates docking sites for intracellular signaling proteins, initiating downstream signal transduction [19].

Classification of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases

Based on primary amino acid sequences and molecular organization, RTKs are classified into distinct families [22]. The ErbB family (Class I), including the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR/ErbB1) and HER2/ErbB2, plays crucial roles in epithelial cell growth [23]. The insulin and IGF-1 receptors (Class II) are critical for metabolic signaling, while platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFR) and colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) belong to Class III [22]. The vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) constitute a separate class (Type IV) primarily regulating vasculogenesis and angiogenesis [20].

Figure 1: General activation mechanism of receptor tyrosine kinases. Growth factor binding induces receptor dimerization, leading to trans-autophosphorylation and downstream signaling cascade initiation.

Structural Basis of Activation

The conformational transition from inactive to active states is a fundamental aspect of receptor function. For EGFR, biophysical studies in live cells demonstrate that in quiescent cells with low receptor expression (<50,000/cell), receptors exist predominantly as monomers [23]. Ligand binding rapidly induces dimer formation, which then associates with clathrin-coated pits for internalization [23]. In contrast, the orphan receptor ErbB2 exists preformed in aggregates of three to eight molecules and larger clusters, even in the absence of ligand [23]. This pre-association may facilitate rapid signaling upon heterodimerization with other ErbB family members.

Comparative Analysis of Major Growth Factor Receptor Families

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptors (VEGFRs)

The VEGF-VEGFR system is a critical regulator of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, with profound implications for tumor biology [20] [24].

Structural Features and Ligand Diversity

VEGF-A, the predominant pro-angiogenic factor, exists in multiple isoforms (VEGF-A121, VEGF-A145, VEGF-A165, VEGF-A189, VEGF-A206) generated through alternative splicing [20] [24]. These isoforms differ in their heparin-binding affinity and extracellular matrix (ECM) retention capabilities due to variations in their C-terminal domains [24]. For example, VEGF-A121 is freely diffusible, while VEGF-A189 and VEGF-A206 tightly bind heparan sulfate proteoglycans, creating steep concentration gradients that guide patterned vascular growth [24]. VEGF-A165, the most abundant isoform, contains both receptor-binding and heparin-binding domains, enabling balanced distribution and signaling [24].

VEGFRs comprise three main members: VEGFR1 (Flt1), VEGFR2 (KDR/Flk1), and VEGFR3 (Flt4) [20]. VEGFR1 binds VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PIGF with very high affinity (Kd ~2-10 pM for VEGF-A) but exhibits weak kinase activity, potentially functioning as a decoy receptor [20]. VEGFR2 serves as the primary mitogenic signal transducer for VEGF-A (Kd ~1-10 nM) and is essential for physiological and pathological angiogenesis [20] [24]. VEGFR3 primarily regulates lymphangiogenesis and binds VEGF-C and VEGF-D [20].

Downstream Effectors and Functional Outcomes

VEGFR2 activation initiates multiple signaling pathways including PLCγ-PKC-MAPK (promoting proliferation), PI3K-Akt (enhancing survival), and FAK-paxillin (regulating migration) [20]. In pathological conditions like cancer, excessive VEGF signaling promotes tumor angiogenesis, creating immature, leaky vessels that facilitate nutrient delivery and metastasis [20] [21].

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors (EGFR/ErbB Family)

The ErbB receptor family consists of four members: EGFR (ErbB1), HER2 (ErbB2), HER3 (ErbB3), and HER4 (ErbB4) [23].

Activation and Signaling Mechanisms

EGFR activation involves ligand-induced conformational changes that promote dimerization [23]. In living cells studied at physiological temperatures, unliganded EGFR exists primarily as monomers at low expression levels, with dimerization occurring predominantly after EGF binding [23]. This contrasts with HER2, which forms pre-existing aggregates and clusters that may facilitate signaling [23]. ErbB receptors form homo- and heterodimers with distinct signaling properties, with the HER2-HER3 heterodimer being particularly potent in activating oncogenic signaling [23].

Downstream Signaling Pathways

Activated EGFR initiates multiple signaling cascades including:

- RAS-RAF-MAPK pathway: Regulates gene expression and cellular proliferation

- PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway: Promotes cell survival and metabolism

- JAK-STAT pathway: Influences gene transcription and immune responses [18]

Dysregulation of these pathways through EGFR overexpression or activating mutations drives uncontrolled cell growth in multiple cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [19].

Other Significant Growth Factor Receptors

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptors (PDGFR)

PDGFRs belong to Class III RTKs and play crucial roles in connective tissue development and wound healing [22]. PDGFR activation stimulates pathways similar to other RTKs, including MAPK and PI3K-Akt, promoting cell proliferation, survival, and migration [25].

Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors (FGFR)

The FGFR family (FGFR1-4) regulates embryonic development, cell growth, differentiation, and angiogenesis [18]. FGFR signaling involves complex interactions with heparan sulfate proteoglycans that modulate receptor-ligand binding and activation.

Therapeutic Targeting: Comparative Efficacy of Signaling Pathway Inhibitors

Targeted therapies against growth factor receptors primarily include monoclonal antibodies and small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [19]. These agents have revolutionized cancer treatment but exhibit distinct efficacy and safety profiles.

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs)

TKIs are small molecules that inhibit the enzymatic activity of the target protein [19]. They are categorized based on their mechanism of action: ATP-competitive inhibitors (binding the active kinase conformation), inhibitors recognizing inactive conformations, allosteric inhibitors (binding outside the ATP pocket), and covalent inhibitors (forming irreversible bonds) [19].

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

| Category | Mechanism of Action | Example Drugs | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-competitive inhibitors | Bind active conformation of ATP-binding site | Gefitinib, Erlotinib | Reversible binding; specificity varies |

| Inactive conformation binders | Recognize and stabilize inactive kinase conformation | Imatinib | Make activation energetically unfavorable |

| Allosteric inhibitors | Bind outside ATP site, modifying 3D structure | - | Disrupt ATP interaction; high specificity |

| Covalent inhibitors | Form irreversible covalent bonds with kinase | Osimertinib, Afatinib | Prolonged inhibition; potential resistance issues |

Comparative Clinical Efficacy in EGFR-Mutant NSCLC

Recent studies directly compare the efficacy of different TKI-based strategies in resectable EGFR-mutant NSCLC:

Table 2: Comparative Efficacy of Neoadjuvant EGFR-TKI Regimens in Resectable NSCLC

| Parameter | EGFR-TKI Monotherapy (N=20) | EGFR-TKI + Chemotherapy (N=30) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological Complete Response (pCR) | 5.0% (1/20) | 20.0% (6/30) | P=0.22 |

| Major Pathological Response (MPR) | 35.0% (7/20) | 36.7% (11/30) | Not significant |

| 3-Year Recurrence-Free Survival (RFS) | 46.7% | 53.4% | P=0.42 |

| RO Resection Rate | 95% | 96.7% | Not significant |

| Grade ≥3 Adverse Events | 0% | 6% (2/30) | - |

This real-world multicenter retrospective study demonstrated that while combination therapy yielded a higher pCR rate (20.0% vs. 5.0%), the MPR rates and long-term RFS were comparable between groups [26] [27]. The combination therapy group experienced higher toxicity, with 6% of patients reporting grade ≥3 adverse events compared to none in the monotherapy group [26]. These findings suggest that while combination strategies may enhance pathological responses, the optimal regimen must balance efficacy with toxicity, considering individual patient and tumor characteristics [27].

Resistance Mechanisms to Targeted Therapies

Despite initial efficacy, acquired resistance often limits long-term benefits of TKI therapy [19]. Major resistance mechanisms include:

- Target modifications: Point mutations (e.g., T790M in EGFR), amplifications, or deletions altering drug binding [19]

- Bypass signaling: Activation of alternative RTKs or downstream effectors that circumvent inhibited targets [19]

- Phenotypic changes: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, enhanced stemness, and metabolic reprogramming [21]

- Tumor microenvironment interactions: Recruitment of pro-angiogenic bone marrow-derived cells and alternative angiogenesis models like vascular mimicry [21]

Overcoming resistance requires combination therapies targeting parallel pathways and sequential treatment strategies based on molecular profiling at progression [19].

Experimental Methodologies for Evaluating Inhibitor Efficacy

Clinical Trial Design and Endpoints

The comparative study of EGFR-TKI regimens followed rigorous methodological standards [26] [27]. Key elements included:

- Study Population: Patients with pathologically confirmed NSCLC, clinical stage II-III, confirmed EGFR mutations, and receipt of at least 4 weeks of neoadjuvant targeted therapy before planned resection [27]

- Staging Methods: Comprehensive evaluation using enhanced chest CT, PET/CT, and brain MRI within 30 days pre-treatment [27]

- Response Assessment: Imaging evaluation using RECIST 1.1 criteria and pathological assessment of tumor regression according to International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) criteria [27]

- Pathological Evaluation: Continuous sectioning of all lesions with tumor bed calculation based on areas of tumor, necrosis, and fibrosis, evaluated by at least two experienced pathologists at each center [27]

Assessment of Treatment Efficacy

Primary endpoints included major pathological response (MPR), defined as ≤10% viable tumor in resected specimens [26]. Secondary endpoints encompassed pathological complete response (pCR), perioperative adverse events, and long-term survival outcomes including recurrence-free survival (RFS) [26] [27]. Surgical outcomes such as R0 resection rate (complete microscopic resection) and the proportion of minimally invasive procedures were also evaluated [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Growth Factor Receptor Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors | Inhibit enzymatic activity of target kinases | Osimertinib, Gefitinib, Erlotinib (EGFR); Sunitinib, Sorafenib (VEGFR) |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Block ligand-receptor interaction or induce receptor internalization | Bevacizumab (VEGF-A); Cetuximab, Panitumumab (EGFR); Trastuzumab (HER2) |

| Receptor Ligands | Activate receptors for signaling studies | VEGF-A isoforms (121, 165, 189); EGF; PDGF |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detect activated/phosphorylated receptors and signaling proteins | Anti-phospho-EGFR; Anti-phospho-Akt; Anti-phospho-ERK |

| Live Cell Imaging Tools | Study receptor dynamics in real-time | GFP-tagged receptors; Quantum dot conjugates; Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy |

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Process growth factor precursors to mature forms | Furin; ADAMTS3 (for VEGF-C processing) |

| Signal Transduction Assays | Measure pathway activation | MAPK pathway reporters; PI3K activity assays; AKT phosphorylation panels |

| MeOSuc-AAPF-CMK | MeOSuc-AAPF-CMK, MF:C26H35ClN4O7, MW:551.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lacutoclax | Lacutoclax (LP-108)|BCL-2 Inhibitor|RUO | Lacutoclax is a selective BCL-2 inhibitor for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

Figure 2: Key growth factor signaling pathways and therapeutic inhibition points. The diagram illustrates VEGF/VEGFR and EGFR signaling cascades with major downstream effectors, showing points of intervention by monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

The structure-function relationships of growth factor receptors and their downstream effectors reveal sophisticated signaling mechanisms that are precisely regulated in health but frequently dysregulated in disease. Comparative studies of therapeutic inhibitors demonstrate that targeting specificity, resistance mechanisms, and combination approaches significantly influence clinical outcomes. While TKI-based therapies have transformed cancer treatment, emerging challenges including therapeutic resistance and adverse effects necessitate continued research into novel targeting strategies. Future directions include developing allosteric inhibitors, covalent TKIs with improved specificity, and rational combination therapies that address compensatory pathways. The integration of structural biology, live-cell imaging, and clinical translation will further advance targeted therapeutic interventions in precision oncology.

Pathway Cross-talk and Compensatory Mechanisms in Tumor Survival

Targeted therapies against specific oncogenic signaling pathways often achieve limited long-term success in oncology due to the remarkable adaptability of cancer cells. This review examines the fundamental mechanisms by which tumors evade pathway inhibition through cross-talk and compensatory signaling, with a focus on combination strategies designed to overcome therapeutic resistance. We analyze experimental data from preclinical and clinical studies targeting key oncogenic pathways, including KRAS, MEK, and receptor tyrosine kinases, providing a comparative assessment of monotherapy versus combination approaches. The synthesized evidence underscores that co-inhibition of primary and compensatory pathways represents a promising strategy to enhance therapeutic efficacy and overcome adaptive resistance in multiple cancer types.

Cancer cells exploit the inherent redundancy and interconnectivity of signaling networks to survive therapeutic insult. When a primary oncogenic driver is targeted, tumors frequently activate alternative or parallel pathways to maintain proliferation and survival signals. This adaptive resistance occurs through multiple mechanisms, including feedback loop activation, bypass signaling, and pathway rewiring. The clinical manifestation of these phenomena is often an initial response followed by disease progression, as observed with many targeted therapies. Understanding these dynamic network interactions is crucial for designing effective long-term treatment strategies that preempt or overcome resistance.

Key Compensatory Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence

KRAS-MEK-ERK Pathway and RTK Feedback

The KRAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling cascade represents a critical oncogenic pathway with well-documented compensatory mechanisms. MEK inhibitors initially suppress ERK phosphorylation and cell proliferation in KRAS-mutant cancers, but this inhibition triggers rapid adaptive resistance through multiple feedback loops.

Experimental Protocol: Researchers treated multiple KRAS-mutant NSCLC cell lines (A549-G12S, H460-Q61H, SK-LU-1-G12D, SW900-G12V) with the MEK inhibitor trametinib for varying durations (3-10 days). Cell proliferation was assessed via MTT assay, apoptosis by flow cytometry with YO-PRO-1/PI staining, cell cycle distribution by propidium iodide staining, and invasion capacity through Transwell assays. Signaling changes were monitored via Western blotting for phosphorylated ERK and AKT. Transcriptomic analysis identified upregulated pathways following sustained MEK inhibition [28].

Table 1: Adaptive Resistance to MEK Inhibition in KRAS-Mutant NSCLC Models

| Cell Line | KRAS Mutation | Short-term Effect (3 days) | ERK Rebound | AKT Activation | Resistance Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | G12S | Growth inhibition | Yes | Yes | 5-10 days |

| H460 | Q61H | Growth inhibition | Yes | Yes | 5-10 days |

| SK-LU-1 | G12D | Growth inhibition | Yes | Yes | 5-10 days |

| SW900 | G12V | Growth inhibition | Yes | Yes | 5-10 days |

| H23 | G12C | Growth inhibition | Moderate | No | >10 days |

Transcriptomic analysis revealed that prolonged trametinib treatment (10 days) significantly upregulated genes in the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway and angiogenesis-related pathways, indicating broad activation of compensatory survival signals. This feedback activation was mediated through multiple receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), creating a biological rationale for combined MEK and RTK inhibition [28].

Clinical Validation of Combination Therapy

The mechanistic understanding of RTK-mediated compensation led to a clinical trial (NCT04967079) evaluating trametinib (MEK inhibitor) plus anlotinib (pan-RTK inhibitor) in advanced non-G12C KRAS-mutant NSCLC patients.

Experimental Protocol: This phase I study enrolled 33 patients with advanced KRAS-mutant NSCLC. Phase Ia (13 patients) established the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) through a 3+3 dose escalation design. Phase Ib (20 patients) further evaluated efficacy and safety at the RP2D. Patients received trametinib (2mg) plus anlotinib (8mg) orally once daily in 21-day cycles. Primary endpoints included objective response rate (ORR) and progression-free survival (PFS). Secondary endpoints included disease control rate (DCR), overall survival (OS), and safety profile. Response assessment followed RECIST 1.1 criteria with CT scans every 6 weeks [28].

Table 2: Clinical Outcomes of MEK/RTK Co-inhibition in KRAS-Mutant NSCLC

| Parameter | Phase Ia (n=13) | Phase Ib (n=20) | Combined (n=33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Response Rate | 69.2% | 65.0% | 66.7% |

| Disease Control Rate | 92.0% | 100.0% | 97.0% |

| Median PFS (months) | 6.9 | 11.5 | 9.2 |

| Median OS (months) | Not reached | 15.5 | Not reached |

| Adverse Events ≥G3 | 23% | 35% | 30% |

The combination therapy demonstrated significantly improved outcomes compared to historical controls of MEK inhibitor monotherapy, which typically shows ORRs of 10-20% in KRAS-mutant NSCLC. The clinical validation of this combination approach effectively demonstrates that preemptive targeting of compensatory mechanisms can enhance therapeutic efficacy [28].

Metabolic Reprogramming as a Compensatory Survival Mechanism

EGFR/Akt-Driven Warburg Effect in Colorectal Cancer

Beyond direct signaling pathway cross-talk, cancer cells employ metabolic reprogramming as a compensatory survival mechanism. In colorectal cancer (CRC), EGFR/Akt signaling promotes the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) through upregulation of hexokinase II (HKII), creating dual pro-survival advantages.

Experimental Protocol: Investigations into the EGFR/Akt/HKII axis involved treating CRC cell lines with xanthohumol, a natural compound that inhibits EGFR phosphorylation. Subsequent Western blot analyses demonstrated downstream Akt and HKII inhibition. Glycolytic rate was measured via extracellular acidification rate, and apoptosis was assessed by Annexin V staining and cytochrome c release. HKII overexpression rescue experiments confirmed the specific role of this metabolic enzyme in compensatory survival [29].

Table 3: Metabolic Adaptations as Compensatory Survival Mechanisms

| Cancer Type | Primary Pathway | Metabolic Adaptation | Key Enzymes/Transporters | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | EGFR/Akt | Aerobic glycolysis | Hexokinase II (HKII) | Enhanced ATP production, apoptosis resistance |

| Various Cancers | Angiogenesis inhibition | Altered energy metabolism | ABCG2 transporter | Chemotherapy efflux, resistance |

| SDH-mutated Cancers | Succinate accumulation | Pseudohypoxia signaling | SUCNR1 receptor | Angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis |

The mitochondrial binding of HKII not only enhances glycolytic flux but also inhibits apoptosis by closing mitochondrial permeability transition pores and preventing cytochrome c release. This dual function represents a sophisticated compensatory mechanism that links metabolic reprogramming with apoptotic resistance [29].

Succinate Receptor Signaling in Tumor Microenvironment

Metabolite sensing through G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) represents another dimension of compensatory signaling. The succinate receptor SUCNR1 (GPR91) activates in response to accumulated succinate, particularly in tumors with succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) mutations.

Experimental Protocol: Studies evaluating SUCNR1 signaling employed succinate stimulation in SDH-mutated cancer cells, followed by Western blot analysis of PI3K-Akt-HIF-1α pathway activation. Invasion and migration were assessed via Boyden chamber assays. Macrophage polarization was evaluated through flow cytometry analysis of surface markers and cytokine secretion profiles after succinate exposure [30].

SUCNR1 activation drives tumor progression through multiple mechanisms: directly promoting cancer cell invasion via PI3K-Akt-HIF-1α signaling, inducing angiogenesis through ERK1/2-STAT3-VEGF activation in gastric cancer, and polarizing tumor-associated macrophages toward an M2 phenotype that secretes pro-migratory cytokines like IL-6. This exemplifies how metabolic byproducts can activate compensatory signaling pathways that support tumor survival under stress conditions [30].

Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Compensatory Mechanisms

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Studying Pathway Cross-talk

| Research Reagent | Specific Example | Research Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEK Inhibitors | Trametinib | Blockade of KRAS downstream signaling | Identified RTK feedback activation |

| Pan-RTK Inhibitors | Anlotinib | Multi-target RTK inhibition | Demonstrated efficacy of MEK/RTK co-inhibition |

| MERTK Inhibitors | UNC2025 | Selective MERTK tyrosine kinase inhibition | Suppressed pro-survival signaling in leukemia |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Xanthohumol | Natural compound targeting EGFR/Akt/HKII axis | Established link between signaling and metabolic reprogramming |

| GPCR Agonists/Antagonists | Succinate (SUCNR1 agonist) | SUCNR1 pathway activation | Revealed metabolite sensing in tumor microenvironment |

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Compensatory Mechanisms

KRAS-MEK-ERK Pathway and RTK Feedback

Metabolic Reprogramming Cross-talk

Discussion and Clinical Implications

The compiled evidence demonstrates that cancer cells employ diverse compensatory mechanisms when confronted with targeted pathway inhibition. These include vertical feedback within the same pathway (ERK rebound after MEK inhibition), horizontal activation of parallel pathways (PI3K-AKT activation following MEK inhibition), and metabolic reprogramming (Warburg effect enhancement through EGFR/Akt/HKII). Successful therapeutic strategies must therefore anticipate and preempt these adaptive responses through rational combination therapies.

The clinical data supporting MEK/RTK co-inhibition in KRAS-mutant NSCLC provides a paradigm for targeting pathway cross-talk, demonstrating significantly improved response rates and progression-free survival compared to historical monotherapy outcomes. Similarly, targeting both signaling and metabolic adaptations, as seen in colorectal cancer models, represents a promising approach for overcoming therapeutic resistance.

Future research directions should focus on identifying predictive biomarkers for specific compensatory mechanisms, allowing personalized combination therapy selection. Additionally, temporal sequencing of targeted therapies to anticipate and intercept resistance evolution may further enhance durable response rates. The continued elucidation of cancer pathway interconnectivity will undoubtedly reveal new therapeutic vulnerabilities and combination strategies to improve patient outcomes.

The evolution of cancer therapy represents a fundamental shift from broad cytotoxic approaches to highly specific molecular interventions. Traditional chemotherapy, characterized by its non-selective mechanism of action on rapidly dividing cells, often resulted in significant toxicity to healthy tissues and variable efficacy. The contemporary era of precision medicine is founded on directly targeting specific molecular alterations that drive cancer pathogenesis, enabled by sophisticated diagnostic technologies that guide therapeutic decision-making [31].

This transition began with early observations of the immune system's role in tumor regression, dating back to the 1700s with documented cases of tumor suppression following erysipelas infections. William Coley's development of Coley's toxins in the late 19th century represented one of the first systematic attempts to harness the immune system against cancer [31]. The modern targeted therapy revolution accelerated with several key developments: the discovery of monoclonal antibodies in 1975, the introduction of imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) targeting BCR-ABL1, and the clinical success of trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer [31]. These milestones established that targeting specific oncogenic drivers could produce dramatic clinical responses with improved therapeutic indices compared to conventional chemotherapy.

The Diagnostic Foundation: Technological Enablers of Precision Medicine

The advancement of targeted therapies is inextricably linked to parallel innovations in molecular diagnostics that enable identification of specific therapeutic targets. Accurate detection of genetic alterations, expression patterns, and protein biomarkers is essential for appropriate patient stratification and treatment selection.

Comparative Performance of Molecular Detection Technologies

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PCR-Based Diagnostic Technologies

| Technology | Detection Principle | Quantification Method | Optimal Use Case | Sensitivity in Low Target Scenarios | Tolerance to Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional PCR | Endpoint amplification | Semi-quantitative (gel electrophoresis) | Target detection in high-concentration samples | Low | Low |

| RT-qPCR | Fluorescence detection during amplification | Relative quantification (Ct values vs. standard curve) | Viral load monitoring, gene expression analysis | Moderate | Moderate |

| Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) | Partitioning and endpoint detection | Absolute quantification (Poisson statistics) | Minimal residual disease, low viral load detection, sequence variants | High | High |

| RT-LAMP | Isothermal amplification with multiple primers | Visual color change or turbidity | Point-of-care testing, resource-limited settings | Variable | High |

Recent technological comparisons reveal distinct performance characteristics across detection platforms. For SARS-CoV-2 detection, RT-qPCR using the CDC protocol demonstrated high accuracy as a diagnostic standard, while RT-LAMP showed lower sensitivity but offered advantages in procedural simplicity [32]. In tuberculosis diagnostics, ddPCR exhibited superior discriminant capacity for extrapulmonary tuberculosis compared to qPCR, with area under the ROC curve values of 0.97 versus 0.94 respectively [33].

For minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring in chronic myeloid leukemia, ddPCR provides absolute quantification of BCR-ABL1 transcripts with reduced variability compared to RT-qPCR. However, this comes with a tradeoff: ddPCR demonstrated a lower proportion of deep molecular responses and required a cutoff of three BCR-ABL1 copies per duplicate to maintain a low false-positive rate (4%) [34]. In acute leukemia diagnostics, RT-qPCR has demonstrated higher sensitivity compared to Nested-PCR for detecting fusion transcripts like RUNX1::RUNX1T1, CBFB::MYH11, and BCR::ABL1 at diagnosis [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Targeted Therapy Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase Kits | High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Enables RNA biomarker analysis and expression studies |

| PCR Master Mixes | Platinum SuperFi II PCR Master Mix, GoTaq Probe qPCR System | Amplification of target sequences with high fidelity | Provides optimized buffer conditions and polymerase for specific PCR applications |

| DNA Polymerases | Pfu polymerase, Taq polymerase | PCR amplification with varying fidelity requirements | Pfu offers proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) for high-fidelity amplification |

| RNA Extraction Kits | QIAmp Viral RNA Kit, TRIzol Reagent | Nucleic acid isolation from clinical samples | Provides high-purity RNA for downstream molecular applications |

| Fluorescent Probes | Hydrolysis probes (TaqMan), DNA binding dyes (SYBR Green) | Real-time detection of amplification products | Enables quantification and detection of specific targets in qPCR and ddPCR |

| Digital PCR Reagents | Droplet generation oil, supermixes | Partitioning and amplification for absolute quantification | Facilitates digital PCR workflow for highly sensitive detection |

| Ala-Ala-Pro-pNA | Ala-Ala-Pro-pNA, MF:C17H23N5O5, MW:377.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dyrk2-IN-1 | Dyrk2-IN-1, MF:C29H31FN8O2S, MW:574.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Key Signaling Pathways and Their Inhibitors

Targeted therapies function through precise intervention in dysregulated signaling networks that govern cellular proliferation, survival, and death. The following diagram illustrates major pathways currently targeted in precision oncology:

The EGFR signaling pathway represents one of the most successfully targeted oncogenic drivers, particularly in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Current first-line approaches for EGFR-mutant NSCLC include osimertinib as a single agent, osimertinib plus chemotherapy, or amivantamab (a bispecific antibody) plus lazertinib [36]. Resistance mechanisms remain a challenge, spurring development of next-generation agents like SYS6010, a novel EGFR-targeting antibody-drug conjugate showing promise in tumors resistant to available treatments [36].

The KRAS pathway, once considered "undruggable," has witnessed remarkable progress with the development of G12C-specific inhibitors (sotorasib, adagrasib). Research is now advancing beyond G12C to target other KRAS mutations, including G12D inhibitors (zoldonrasib/RMC-9805) and pan-KRAS inhibitors (AMG410) that target all KRAS mutation types while sparing wild-type KRAS signaling [36].

Experimental Workflows for Therapeutic Assessment

The development and evaluation of targeted therapies requires standardized methodologies to assess both compound efficacy and accompanying diagnostic approaches. The following diagram outlines a representative workflow for evaluating signaling pathway inhibitors:

Protocol: RT-ddPCR for Low-Abundance Transcript Detection

The accurate quantification of low-abundance targets is essential for monitoring minimal residual disease and assessing targeted therapy response. The following protocol is adapted from SARS-CoV-2 research but demonstrates principles applicable to oncology biomarkers [37]:

Sample Preparation:

- Obtain RNA from patient samples (blood, tissue, or other relevant biospecimens) using commercial extraction kits (e.g., QIAmp Viral RNA Kit)

- Quantify RNA using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop2000) and standardize concentration to 20 ng/μL

- Assess RNA quality using 260/280 nm ratio; samples with ratios between 1.8-2.0 are considered high purity

Reverse Transcription:

- Perform cDNA synthesis using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit

- Use 20 μL RNA template per reaction

- Conduct reverse transcription in a thermal cycler with the following conditions: 10 minutes at 25°C, 120 minutes at 37°C, 5 minutes at 85°C

Droplet Digital PCR:

- Prepare reaction mix containing:

- 10 μL ddPCR Supermix

- 1 μL multiplexed primer/probe sets (targeting genes of interest and reference genes)

- 5 μL cDNA template

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL final volume

- Generate droplets using droplet generator

- Transfer droplets to a 96-well PCR plate and seal

- Perform PCR amplification with the following conditions:

- 95°C for 10 minutes (enzyme activation)

- 40 cycles of: 94°C for 30 seconds (denaturation) and 60°C for 60 seconds (annealing/extension)

- 98°C for 10 minutes (enzyme deactivation)

- Read plate on droplet reader and analyze using Poisson statistics for absolute quantification

This protocol's key advantage is its ability to detect sequence mismatches through differential fluorescence amplitude, providing insights into tumor evolution and heterogeneity [37].

Protocol: Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis for Therapy Monitoring

Liquid biopsy approaches using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) have transformed monitoring of targeted therapy response and resistance emergence:

Sample Collection and Processing: