Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer in Buffalo Embryos: Protocols, Challenges, and Future Directions for Transgenesis

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) for generating transgenic buffalo embryos.

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer in Buffalo Embryos: Protocols, Challenges, and Future Directions for Transgenesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) for generating transgenic buffalo embryos. It explores the foundational principles of sperm biology and gene uptake, details established and novel protocols including DMSO and nanoparticle-based methods, and addresses critical challenges in efficiency and reproducibility. The content also covers advanced validation techniques, from molecular to phenotypic assessment, and discusses the implications of this technology for biomedical research and livestock improvement. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to guide future experimental design and application in this promising field.

Understanding Buffalo Sperm Biology and the Fundamentals of Gene Transfer

The Egyptian river buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) is a crucial livestock species with significant economic and cultural value, contributing substantially to milk and meat production. Global climate change threatens livestock production, particularly in regions like Egypt where heat stress significantly diminishes fertility. This species exhibits distinctive reproductive characteristics, including seasonal patterns in semen quality, sensitivity to thermal stress, and specific molecular responses in spermatozoa and seminal plasma. Recent advances in molecular genetics and reproductive biotechnologies have transformed the understanding and manipulation of buffalo reproduction. This overview details the unique aspects of Egyptian buffalo reproductive biology, with a specific focus on applications for sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) research, providing detailed protocols and resources to support experimental work in this field.

Biological Distinctives of Egyptian Buffalo Reproduction

Seasonal Impact on Semen Quality and Molecular Composition

The reproductive performance of Egyptian buffalo bulls exhibits marked seasonal variation, with optimal function during winter months. A 2025 study comprehensively analyzed semen quality, oxidative stress markers, and seminal extracellular vesicles (SP-EVs) across seasons, revealing significant biological differences [1].

Table 1: Seasonal Impact on Semen Quality and Oxidative Stress Parameters in Egyptian Buffalo Bulls

| Parameter | High-Quality Sperm (HQS) Winter | High-Quality Sperm (HQS) Summer | Low-Quality Sperm (LQS) Winter | Low-Quality Sperm (LQS) Summer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Motility (%) | 79.4 ± 0.65 | 69.9 ± 0.65 | - | - |

| Normal Morphology (%) | 75.5 ± 0.87 | 71.3 ± 0.87 | - | - |

| MDA (nmol/ml) | 0.71 ± 0.25 | 4.76 ± 0.18 | 2.62 ± 1.21 | 1.31 ± 1.67 |

| SOD (U/ml) | 186.7 ± 0.87 | 292.0 ± 3.93 | 191.2 ± 2.88 | - |

| CAT (U/ml) | - | 949.7 ± 15.23 | 459.7 ± 19.04 | - |

| GPx (mU/ml) | - | 77.7 ± 2.15 | 35.5 ± 2.48 | - |

SP-EVs from low-quality semen during winter showed increased expression of surface markers CD9 (91.15%) and CD63 (96.08%), suggesting their potential role as biomarkers for oxidative damage. Conversely, SP-EVs from high-quality semen were smaller and associated with upregulated antioxidant genes (SOD, NFE2L2) and downregulated apoptotic markers (CASP3) [1].

Genetic Architecture of Semen Traits

Genome-wide association studies have identified specific genomic regions associated with semen traits in Egyptian buffalo bulls. The X-chromosome accounts for substantial proportions of genomic variance across multiple semen parameters [2]:

- Ejaculate volume: 4.18%

- Mass motility: 4.59%

- Livability: 5.16%

- Abnormality: 5.19%

- Concentration: 4.31%

These findings highlight the chromosomal importance for male fertility traits and suggest potential candidate genes for spermatogenesis and male fertility within these genomic regions [2].

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) in Egyptian Buffalo

SMGT represents a simplified and cost-effective approach for producing transgenic animals by exploiting the natural ability of sperm cells to bind, internalize, and transport foreign DNA into oocytes during fertilization [3]. This technique is particularly valuable for buffalo transgenesis, which aims to enhance production characteristics like milk yield, growth rate, disease resistance, and reproductive performance [3].

Optimized SMGT Protocol for Egyptian Buffalo

The following protocol was established specifically for Egyptian buffalo sperm, optimizing conditions for transgene integration while maintaining sperm viability and function [3] [4] [5].

Table 2: Optimized SMGT Parameters for Egyptian Buffalo Sperm

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Alternative Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm Concentration | 10×10ⶠcells/ml | - |

| DNA Concentration | 20 µg/ml linearized plasmid | - |

| Transfection Agent | 3% Dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) | ZIF-8 nanoparticles (emerging approach) |

| Incubation Time | 15 minutes | - |

| Incubation Temperature | 4°C | - |

| Plasmid Type | pEGFP-N1 (linearized with AseI) | pEGFP-IRES-Neo (for SCNT) |

| Selection Method | - | G418 (600 µg/mL for 7-14 days for somatic cells) |

Detailed SMGT Methodology

Reagent Preparation

- Prepare sperm-TALP medium: 100 mM NaCl, 3.1 mM KCl, 25.0 mM NaHCO₃, 0.3 mM NaH₂PO₄, 2.16 mM lactate, 2.0 mM CaCl₂, 0.4 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM HEPES, 1.0 mM pyruvate [3].

- Linearize plasmid DNA (pEGFP-N1) using AseI restriction enzyme. Verify complete linearization by agarose gel electrophoresis [3].

- Prepare DMSO stock solution at appropriate concentration to achieve 3% final concentration in sperm-DNA mixture.

Sperm Preparation and Transfection

- Thaw frozen buffalo semen from fertile bulls at 37°C for 40 seconds [3].

- Separate motile spermatozoa using density gradient centrifugation.

- Adjust sperm concentration to 10×10ⶠcells/ml in sperm-TALP medium.

- Combine sperm suspension with linearized DNA (20 µg/ml) and DMSO (3% final concentration).

- Incubate mixture for 15 minutes at 4°C [3].

- Centrifuge at 300×g for 5 minutes to remove unbound DNA.

- Resuspend transfected sperm in appropriate medium for subsequent use in in vitro fertilization.

Validation and Assessment

- Assess sperm viability using one-step eosin-nigrosin staining: live sperm appear white (eosin-impermeable), dead sperm appear pink (eosin-permeable) [3].

- Evaluate transfection efficiency by examining EGFP expression in subsequent embryos using fluorescence microscopy.

Alternative Transgenesis Approaches

While SMGT offers simplicity, other methods have been successfully applied to buffalo transgenesis:

Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT)

- Electroporation proved more efficient (35.5% transfection efficiency) than lipofection methods for transfecting buffalo fetal fibroblasts [6].

- Vector structure significantly influences development, with pEGFP-IRES-Neo yielding higher blastocyst formation rates (21.55%) compared to pEGFP-N1 (16.39%) [6].

- Transgenic cloned buffalo embryos expressed EGFP strongly in testis, fat, kidney, and intestines, with weaker expression in muscle, diaphragm, heart, lung, and spleen [6].

Nanoparticle-Mediated Gene Delivery

- ZIF-8 (zeolitic imidazolate framework-8) nanoparticles show promise as novel vectors for enhancing genetic transfer in SMGT [7].

- ZIF-8 efficiently loads and delivers exogenous DNA into mouse sperm cells, increasing GFP expression in vitro, suggesting potential for buffalo applications [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Buffalo SMGT Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Plasmids | pEGFP-N1, pEGFP-IRES-Neo | Visual tracking of transgene expression; CMV or human elongation factor promoters drive expression |

| Transfection Agents | DMSO (3%), ZIF-8 nanoparticles | Enhance DNA uptake by sperm cells; chemical permeabilization or nano-carrier delivery |

| Assessment Stains | Eosin-nigrosin stain | Differentiate live (white) vs. dead (pink) sperm for viability assessment |

| Culture Media | Sperm-TALP, TCM199 + supplements | Maintain sperm functionality and support in vitro embryo production |

| Selection Agents | G418 (Geneticin) | Antibiotic selection for stably transfected cells (typically 600 µg/mL for 7-14 days) |

| Molecular Biology Tools | AseI restriction enzyme, PCR reagents | Linearize plasmid DNA; verify transgene integration |

| Seminal EV Markers | CD9, CD63 antibodies | Characterize seminal extracellular vesicles as potential fertility biomarkers |

| Dhfr-IN-16 | Dhfr-IN-16, MF:C32H34N4O4S, MW:570.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cyclosporin A acetate-d4 | Cyclosporin A acetate-d4, MF:C64H113N11O13, MW:1248.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

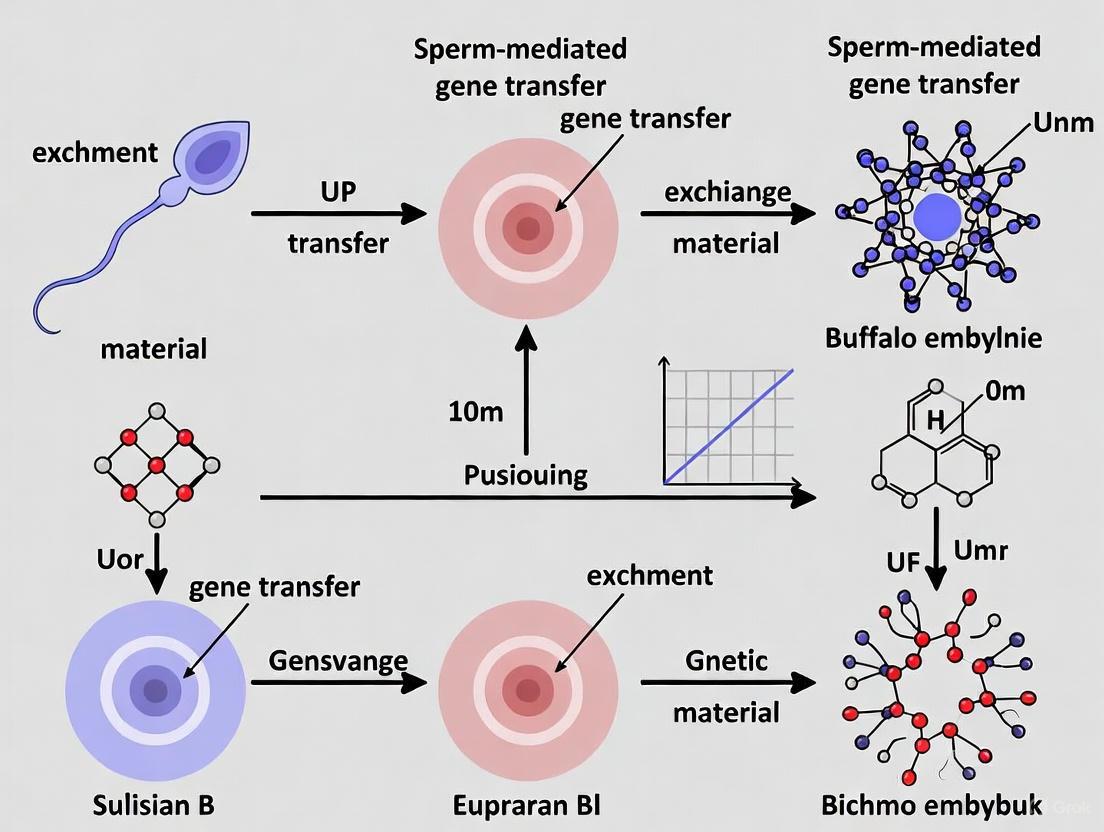

SMGT Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete SMGT workflow for producing transgenic buffalo embryos, from sperm preparation to embryo transfer:

The unique reproductive biology of the Egyptian buffalo, characterized by seasonal fertility patterns, distinct genetic architecture for semen traits, and responsiveness to SMGT approaches, presents both challenges and opportunities for transgenic research. The optimized SMGT protocol detailed here provides a foundation for efficient production of transgenic buffalo embryos, with potential applications for enhancing economically important traits. The incorporation of emerging technologies, including nanoparticle-mediated gene delivery and genomic selection based on seminal traits, promises to further advance the field. Standardized assessment of semen quality, particularly considering seasonal variations and molecular markers such as SP-EVs, remains crucial for successful application of SMGT and other reproductive biotechnologies in this economically significant species.

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) is a transgenic technique that leverages the innate ability of spermatozoa to spontaneously bind to and internalize exogenous DNA and RNA molecules, subsequently transporting this foreign genetic material into an oocyte during fertilization to produce genetically modified animals [8]. Since the creation of the first transgenic mouse using this method in the early 1990s, SMGT has attracted significant interest due to its procedural simplicity compared to other transgenic technologies [9]. The core premise of SMGT utilizes the sperm cell itself as a natural vector for genetic material [8]. For buffalo research, SMGT represents a potentially cost-effective and efficient approach for generating transgenic animals, thereby augmenting their value in biomedical studies and commercial utilization, although the technique requires further refinement to improve its efficiency [7].

Core Mechanisms of SMGT

The process of sperm-mediated gene transfer can be broken down into three distinct, critical steps, each governed by specific molecular interactions.

DNA Binding to the Sperm Cell Surface

The initial step involves the binding of exogenous DNA to the cell membrane of the sperm head. This interaction is not a random event but is instead mediated by specific DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) present on the sperm surface [8]. A significant natural barrier to this process in mammals is an inhibitory factor present in the seminal fluid, which blocks the binding of sperm cells and exogenous DNA by causing DBPs to lose their DNA-binding capability [8]. Therefore, for SMGT to be successful, the seminal fluid must be removed from sperm samples through extensive washing immediately after ejaculation [8]. Research indicates that the binding is also influenced by factors such as sperm concentration, DNA concentration, and the presence of transfecting agents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [4].

Internalization of Foreign DNA

Following surface binding, the exogenous DNA must be internalized into the sperm nucleus. The compact, protamine-bound nature of sperm chromatin was once thought to make this internalization impossible, but numerous studies have confirmed that it occurs [9] [8]. The precise mechanism of internalization is not fully understood, but it is an active process regulated by a network of specific cellular factors [10]. Sperm cells possess an endogenous reverse transcriptase (RT) activity, encoded by LINE-1 retrotransposons, which can reverse-transcribe internalized RNA molecules into cDNA copies. For foreign DNA, it is suggested that a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase first transcribes it into RNA, which is then reverse-transcribed by RT [10]. This process can create multiple cDNA copies, amplifying the foreign genetic information within the sperm population.

Integration and Transport into the Oocyte

The final step involves the integration of the exogenous genetic material into the genome, though this step does not always occur. Internalized DNA or cDNA can be maintained as extrachromosomal, low-copy number sequences [10]. During fertilization, the transfected spermatozoon delivers both its own genome and the foreign genetic material to the oocyte. The exact mechanism of integration into the embryonic genome is complex and can happen at various stages, such as oocyte activation, paternal nucleus decondensation, or during the formation of the pronuclei [8]. The resulting sequences are mosaic distributed in the tissues of the founder animal and can be transmitted to the next generation in a non-Mendelian fashion [10].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of DNA uptake and transport in SMGT:

Optimized SMGT Protocol for Buffalo Embryo Research

This protocol is adapted from a study on Egyptian river buffalo and is designed to optimize the uptake of a linearized plasmid (e.g., pEGFP-N1) by buffalo spermatozoa [4].

Reagent Preparation

- Sperm Washing Medium: Use a commercial semen washing buffer or modified TL-HEPES. Pre-warm to 37°C.

- Transfection Medium: Prepare the basic sperm incubation medium (e.g., modified TL-HEPES). Freshly add Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 3% (v/v) and the linearized plasmid DNA to a final concentration of 20 µg/mL.

- DNA Vector: Linearize the plasmid vector (e.g., pEGFP-N1) using an appropriate restriction enzyme and purify it. Resuspend in TE buffer or nuclease-free water. A concentration of 1 µg/µL is recommended for easy dilution.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Semen Collection and Washing: Collect fresh buffalo semen via artificial vagina. Dilute the semen in 10 mL of pre-warmed washing medium and centrifuge at 750× g for 10 minutes. Carefully aspirate and discard the supernatant, including the seminal plasma layer. Repeat this washing step twice to ensure complete removal of seminal inhibitory factors [8].

- Sperm Concentration Adjustment: After the final wash, resuspend the sperm pellet in transfection medium (without DMSO or DNA). Assess sperm concentration using a hemocytometer and adjust to a final concentration of 1 × 10^7 sperm/mL using the transfection medium [4].

- DNA Transfection Incubation: Add the required volume of the 3% DMSO and 20 µg/mL DNA transfection medium to the sperm suspension. Mix gently by swirling. Incubate the mixture for 15 minutes at 4°C [4].

- Post-Transfection Wash and Assessment: After incubation, centrifuge the sperm-DNA mixture at 750× g for 5 minutes to remove the excess DNA and DMSO. Resuspend the transfected sperm pellet in a clean fertilization medium. Assess sperm quality parameters, including motility and viability, before proceeding to in vitro fertilization (IVF) [11].

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Use the transfected sperm for standard IVF procedures with matured buffalo oocytes. Culture the resulting embryos and screen for transgene integration and expression, for instance, by observing EGFP fluorescence [4].

Key Optimization Parameters

The table below summarizes the critical parameters optimized for efficient SMGT in buffalo sperm, as identified in the foundational study [4].

Table 1: Optimized SMGT Conditions for Buffalo Spermatozoa

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm Concentration | 1 × 10^7 cells/mL | Ensures an optimal cell-to-DNA contact ratio for efficient uptake. |

| DNA Concentration | 20 µg/mL | Provides a saturating yet non-toxic amount of genetic material for binding. |

| Transfecting Agent | 3% DMSO (v/v) | Increases membrane permeability, facilitating DNA internalization [4]. |

| Incubation Time | 15 minutes | Allows sufficient time for DNA binding and uptake while minimizing damage. |

| Incubation Temperature | 4°C | Slows down metabolic activity, potentially reducing DNA degradation and preserving sperm function. |

Advanced SMGT Techniques and Enhancements

While simple incubation with DMSO is effective, several advanced techniques have been developed to significantly improve the efficiency of DNA uptake by sperm cells.

Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery

The use of nanoparticles represents a cutting-edge approach to enhance SMGT. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8), a type of metal-organic framework (MOF), has shown great promise as a vector for exogenous DNA [7]. ZIF-8 can efficiently load and deliver plasmid DNA into mouse sperm cells, resulting in increased transgene expression in vitro [7]. Its unique porous structure protects the DNA and facilitates its entry into sperm cells, offering a potentially more efficient and less damaging alternative to chemical methods.

MBCD-Sperm-Mediated Gene Editing (MBCD-SMGE)

This advanced technique combines SMGT with the CRISPR/Cas9 system for targeted gene editing. Treatment of mouse sperm with Methyl β-Cyclodextrin (MBCD) in a protein-free medium serves two purposes: it removes cholesterol from the sperm membrane, and it increases extracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [12]. This enhances the uptake of the CRISPR/Cas9 system (delivered as a plasmid). The transfected sperm is then used for IVF, leading to the production of targeted mutant blastocysts and offspring with high efficiency, a method known as MBCD-sperm-mediated gene editing (MBCD-SMGE) [12].

Electroporation-Based Delivery

Electroporation is a physical method that uses electrical pulses to create temporary pores in the sperm membrane, allowing for the direct entry of molecules like CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs). This method, known as CRISPR RNP electroporation of zygote (CRISPR-EP), has been standardized in buffalo embryos. Optimal parameters include 20 V/mm, 5 pulses, 3 msec, at 10 hours post-insemination, which increases knockout efficiency without compromising embryonic development [13].

The workflow below illustrates the process of utilizing these advanced gene-editing techniques with sperm:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SMGT Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in SMGT | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A chemical transfection agent that increases sperm cell membrane permeability to exogenous DNA. | Used at 3% concentration in SMGT protocols for buffalo sperm [4]. |

| Methyl β-Cyclodextrin (MBCD) | Removes cholesterol from the sperm membrane, inducing changes that enhance the uptake of large gene-editing constructs. | Key component of the MBCD-SMGE protocol for producing targeted mutant mice [12]. |

| ZIF-8 Nanoparticles | Metal-organic framework nanoparticles that act as protective carriers for DNA, enhancing its delivery into sperm cells. | Demonstrated to efficiently deliver a GFP plasmid into mouse sperm, increasing expression [7]. |

| Linearized Plasmid DNA | The exogenous genetic construct containing the gene of interest and necessary regulatory elements. | pEGFP-N1 plasmid used for optimizing buffalo SMGT; must be linearized for higher efficiency [4]. |

| Electroporation Buffer | A specific, low-conductivity buffer used during electroporation to facilitate efficient electrical pulse delivery and molecule uptake. | Essential for CRISPR-EP methods in buffalo zygotes to deliver RNP complexes [13]. |

| Spns2-IN-1 | Spns2-IN-1|SPNS2 Inhibitor|For Research | Spns2-IN-1 is a potent SPNS2-dependent S1P transport inhibitor (IC50=1.4 µM). For research use only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Lta4H-IN-2 | Lta4H-IN-2, MF:C20H19FN6O2, MW:394.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

SMGT is founded on the core principles of spontaneous DNA binding, active internalization, and subsequent delivery to the oocyte. While the technique faces challenges related to efficiency and reproducibility, optimized protocols involving DMSO and advanced methods using nanoparticles, MBCD, and electroporation are paving the way for more reliable production of transgenic and genome-edited buffalo embryos. The continuous refinement of these protocols holds enormous promise for modeling human diseases, improving desirable traits in livestock, and advancing fundamental research in reproductive biology.

Within the framework of sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) research for the production of transgenic buffalo embryos, the quality of the sperm vector is a paramount determinant of success. Global climate change threatens livestock production, with heat stress being a leading factor diminishing fertility in water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), a species of critical agricultural importance in many regions [1] [14]. This application note synthesizes recent findings on the seasonal variation of buffalo sperm quality and its molecular underpinnings, providing evidence-based protocols to optimize the timing and efficiency of SMGT experiments. A profound understanding of these seasonal impacts is not merely beneficial but essential for standardizing experimental conditions, improving transfection efficiency, and enhancing the overall reproducibility of SMGT protocols in this species.

Comprehensive studies on Egyptian buffalo bulls have quantified the significant degradation of sperm quality during the summer months compared to winter, providing critical baseline data for SMGT experimental planning.

Table 1: Seasonal Comparison of Key Sperm Quality Parameters in Buffalo

| Parameter | Summer Season | Winter Season | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Motility (%) | 69.9 ± 0.65 (HQS)50.4 ± 0.65 (LQS) | 79.4 ± 0.65 (HQS) | P < 0.001 [1] |

| Normal Morphology (%) | 71.3 ± 0.87 (HQS)53.0 ± 0.87 (LQS) | 75.5 ± 0.87 (HQS) | P < 0.001 [1] |

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) - Lipid Peroxidation (nmol/ml) | 4.76 ± 0.18 (HQS)1.31 ± 1.67 (LQS) | 0.71 ± 0.25 (HQS)2.62 ± 1.21 (LQS) | P < 0.05 [1] |

| Antioxidant Enzyme - SOD (U/ml) | 292.0 ± 3.93 (HQS) | 186.7 ± 0.87 (HQS) | P < 0.05 [1] |

The data reveal that semen quality peaks consistently in the winter, with bulls classified as having High-Quality Sperm (HQS) exhibiting superior total motility and normal morphology [1]. Furthermore, the elevated concentrations of Malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of oxidative stress, in LQS (Low-Quality Sperm) semen, particularly during summer, indicate greater molecular damage [1]. Conversely, HQS semen demonstrates a more robust antioxidant defense, with significantly elevated activity of key enzymes like Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), especially during the summer stress period [1]. This biochemical resilience is a key trait for selecting sperm donors for SMGT.

Molecular Mechanisms: Oxidative Stress, Extracellular Vesicles, and Epigenetics

The seasonal variation in sperm quality is driven by molecular and cellular events that have direct implications for the sperm's capacity to internalize and safeguard foreign DNA.

Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defenses

Heat stress disrupts the delicate balance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant capacity in the male reproductive tract. The observed seasonal increase in lipid peroxidation (as measured by MDA) directly damages the sperm plasma membrane, which is critical for the DNA binding and internalization processes fundamental to SMGT [1]. The concomitant upregulation of antioxidant genes (SOD, NFE2L2) and downregulation of apoptotic markers (CASP3) in HQS sperm represents a protective molecular profile that is conducive to sperm viability during gene transfer manipulations [1].

Role of Seminal Plasma Extracellular Vesicles (SP-EVs)

Seminal Plasma Extracellular Vesicles (SP-EVs), including prostasomes and epididymosomes, are nano-sized vesicles crucial for intercellular communication, sperm maturation, and protection [1] [14]. Recent characterizations show that SP-EVs from LQS bulls are larger and exhibit increased expression of surface markers (CD9 and CD63), suggesting an association with oxidative damage pathways [1]. In contrast, SP-EVs from HQS bulls are smaller and carry a cargo that may promote cellular stress tolerance. The cargo of SP-EVs is a critical factor for sperm resilience and should be a consideration in SMGT protocol development.

Signaling Pathway Underlying Seasonal Stress Response

The following diagram summarizes the integrated molecular response to seasonal heat stress in buffalo sperm, highlighting the pathways that differentiate High-Quality Sperm (HQS) from Low-Quality Sperm (LQS).

Implications for Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT)

The foundational SMGT study in Egyptian river buffalo established a protocol for inserting the pEGFP-N1 gene construct into sperm, which is the critical first step for producing transgenic embryos [3] [15] [5]. The seasonal factors discussed herein have a profound impact on the success of each stage of this protocol:

- Sperm-DNA Binding and Internalization: The integrity of the sperm plasma membrane, which is compromised by seasonal oxidative stress (as indicated by high MDA), is crucial for the efficient binding and uptake of exogenous DNA. Using HQS sperm from winter collections likely enhances the ratio of successful gene insertion.

- Sperm Viability and Fertility: The superior post-thaw motility and vitality of winter-collected sperm, as historically noted [16], are essential for withstanding the additional stress of transfection (e.g., DMSO treatment) and for achieving successful fertilization in subsequent in vitro embryo production.

- Quality of Transgenic Embryos: The ultimate success of SMGT is measured by the production of viable, transgenic embryos. Starting with HQS sperm, characterized by lower epigenetic and oxidative damage, provides a higher quality genomic template for development, potentially increasing blastocyst formation rates and transgene expression.

Recommended Protocols for SMGT Experimental Timing and Procedures

Seasonal Sample Collection and Quality Control

- Primary Collection Period: Schedule bulk semen collection for SMGT experiments during the winter months (e.g., November to February in the Northern Hemisphere) to capitalize on peak sperm motility and morphology [1].

- Donor Stratification: Implement a rigorous pre-selection of donor bulls based on semen quality. Classify donors into HQS and LQS categories based on total motility (≥70%) and normal morphology (≥70%) as benchmark values [1].

- Oxidative Stress Assessment: Integrate the measurement of Malondialdehyde (MDA) and Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) in seminal plasma as part of the quality control protocol before proceeding to SMGT. Prefer sperm with low MDA and high TAC.

Detailed SMGT Protocol for Buffalo Sperm

The following workflow and detailed steps are adapted from the first successful SMGT study in Egyptian river buffalo [3] [5].

Step 1: Preparation of Linearized DNA Vector

- Use a pure plasmid construct (e.g., pEGFP-N1 for reporter gene expression).

- Linearize the plasmid using an appropriate restriction enzyme (e.g., AseI) to facilitate genomic integration.

- Confirm linearization via agarose gel electrophoresis. Use a final concentration of 20 µg/ml of linearized DNA for the transfection incubation [3] [5].

Step 2: Buffalo Sperm Preparation

- Thaw frozen semen from a pre-selected HQS donor (winter collection) in a 37°C water bath for 40 seconds.

- Wash sperm by centrifugation (e.g., 300-500 x g for 10 minutes) in Sperm-TALP medium to remove the cryopreservation extender.

- Resuspend the sperm pellet in fresh Sperm-TALP to a final concentration of 10â· sperm/ml [3] [5].

Step 3: Sperm Transfection Incubation

Step 4: Assessment of Transfection Efficiency

- Post-incubation, wash the sperm to remove unbound DNA and DMSO.

- Assess transfection success by screening for the presence of the transgene (e.g., via PCR) or, for reporter genes like EGFP, by visualizing fluorescence under a microscope prior to IVF.

Step 5: In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) and Embryo Culture

- Use the transfected sperm for standard IVF procedures with in vitro-matured buffalo Cumulus-Oocyte Complexes (COCs).

- Culture the resulting embryos and screen for transgenic embryos at the appropriate developmental stages (e.g., blastocyst) [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Buffalo SMGT Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm-TALP Medium | Washing and capacitation of buffalo spermatozoa for IVF and SMGT. | Contains specific ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Cl-) and energy substrates (lactate, pyruvate) to maintain sperm viability and function [3]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Transfection agent to facilitate the uptake of exogenous DNA by sperm cells. | A concentration of 3% (v/v) was identified as optimal for Egyptian buffalo sperm without excessive toxicity [3] [5]. |

| Linearized Plasmid DNA (e.g., pEGFP-N1) | Gene construct for transfer; contains the gene of interest and reporter/selection markers. | Must be linearized (e.g., with AseI). A concentration of 20 µg/ml is used for incubation [3] [5]. |

| Antibiotics (Kanamycin/Neomycin) | Selection pressure for bacterial propagation of the plasmid. | pEGFP-N1 contains a kanamycin/neomycin resistance gene for selection in bacteria [3]. |

| Eosin-Nigrosin Stain | Vital staining to assess sperm membrane integrity and viability after treatments like DMSO exposure. | Live sperm remain white (eosin-impermeable); dead sperm stain pink [3]. |

| CD9 & CD63 Antibodies | Characterization of Seminal Plasma Extracellular Vesicles (SP-EVs) via flow cytometry. | Surface markers used to identify and profile SP-EVs, which are biomarkers for sperm quality [1] [14]. |

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) Assay Kit | Quantification of lipid peroxidation as a key marker of oxidative stress in sperm and seminal plasma. | Critical for quality control and stratification of semen samples into HQS vs LQS [1]. |

| Akt-IN-14 | Akt-IN-14, MF:C22H22BrClF2N4OS, MW:543.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tpa-nac | Tpa-nac, MF:C38H33N3O8S2, MW:723.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of seasonal biology into the experimental design of SMGT is a strategic imperative for enhancing the efficiency of transgenic buffalo production. The compelling data show that winter provides a physiologically optimal window for collecting high-quality sperm vectors with superior motility, morphology, and—most importantly—resilience to oxidative stress. By adopting the detailed protocols for seasonal donor management, sperm quality assessment, and the optimized SMGT transfection conditions outlined in this document, researchers can significantly standardize and improve the outcomes of their experiments. This evidence-based approach ensures that SMGT research in buffaloes progresses on a foundation of rigorous and reproducible science, ultimately contributing to the genetic improvement of this vital livestock species.

Application Notes & Protocols

Within the Context of Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer in Buffalo Embryos

Male infertility is a significant concern in both human medicine and animal reproduction, with approximately 30-50% of cases diagnosed as idiopathic or of unknown origin [17]. Traditional semen analysis according to WHO guidelines has demonstrated limited power to predict individual fertility potential, creating an urgent need for more reliable biomarkers [17]. Within the specific context of buffalo reproduction, where sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) offers promising avenues for genetic improvement, understanding the molecular hallmarks of sperm fertility becomes particularly crucial. Buffaloes present unique reproductive challenges, including seasonal breeding patterns, silent heat, and lower conception rates, which complicate traditional breeding programs [18]. The emergence of advanced omics technologies has revolutionized our comprehension of male fertility by identifying potential infertility biomarkers and reproductive defects at the molecular level [19]. This application note synthesizes current proteomic and transcriptomic findings on sperm fertility markers and provides detailed experimental protocols for their identification and validation, with specific application to buffalo SMGT research.

Comparative Molecular Profiles of High and Low Fertility Sperm

Transcriptomic Signatures

Comparative transcriptomic analyses reveal distinct gene expression patterns between high- and low-fertility sperm across species. In crossbred bulls, spermatozoa from high-fertility individuals contained transcripts for 13,563 genes, with 2,093 unique to high-fertile and 5,454 unique to low-fertile bulls [20]. After normalization, 84 transcripts were unique to high-fertile and 168 to low-fertile bulls, with 176 transcripts upregulated and 209 downregulated in low-fertile bulls [20]. Gene ontology analysis identified that sperm transcripts involved in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway and biological processes such as multicellular organism development, spermatogenesis, and in utero embryonic development were significantly downregulated in low-fertile crossbred bull sperm [20].

In human sperm subpopulations, comparative transcriptome analyses of high (F1) and low (F2) motility sperm identified 82 differentially expressed genes [17]. Notably, CEP128 and CSTPP1 were significantly downregulated in the low-motility F2 fraction, and this downregulation was confirmed at both the RNA and protein levels [17]. These genes are implicated in centrosomal function and sperm structural integrity, providing a molecular explanation for observed functional deficiencies.

Table 1: Key Transcriptomic Biomarkers of Sperm Fertility

| Gene Symbol | Expression in High Fertility | Function | Validation Method | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEP128 | Upregulated | Centrosomal function, sperm motility | qPCR, Western Blot | Human [17] |

| CSTPP1 | Upregulated | Sperm structural integrity | qPCR | Human [17] |

| ZNF706 | Upregulated | Transcriptional regulation | RT-qPCR | Crossbred Bull [20] |

| CRISP2 | Upregulated | Sperm-egg interaction | RT-qPCR | Crossbred Bull [20] |

| TNP2 | Upregulated | Chromatin condensation | RT-qPCR | Crossbred Bull [20] |

| TNP1 | Upregulated | Chromatin packaging | RT-qPCR | Crossbred Bull [20] |

Proteomic Landscapes

Proteomic analyses have identified numerous proteins with differential abundance in high versus low-fertility sperm. In human studies, comprehensive proteomic profiling of sperm from subfertile men (asthenozoospermic and oligoasthenozoospermic) versus normozoospermic controls identified 4,412 proteins, with 1,336 differentially abundant proteins across 70% of samples [21]. In subfertile men, 32 proteins showed lower abundance and 34 showed higher abundance compared to normozoospermic men [21].

Specific protein combinations showed remarkable diagnostic potential. The combination of APCS, APOE, and FLOT1 discriminated subfertile males from normozoospermic controls with an AUC value of 0.95, while combined APOE and FN1 proteins discriminated asthenozoospermic men from controls with an AUC of 1.0 [21]. In the endangered Red Wolf, highly cryo-resilient ejaculates showed significantly higher expression of A1BG, APBB1, KRT1, KRT10, LOC609402 and LOC100685620 proteins in seminal plasma, and significantly reduced expression of RHOA, NUP62, SMYD4, ARHGD1B, CAPG, CSTB, and CFL1 proteins in sperm compared with baseline cryo-resilient samples [22].

Table 2: Proteomic Biomarkers of Sperm Fertility and Cryo-Resilience

| Protein Symbol | Association With | Biological Function | Species | Diagnostic Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE | Asthenozoospermia | Lipid metabolism | Human [21] | AUC=1.0 with FN1 for asthenozoospermia |

| FN1 | Asthenozoospermia | Extracellular matrix organization | Human [21] | AUC=1.0 with APOE for asthenozoospermia |

| APCS | Subfertility | Innate immune response | Human [21] | Part of panel (AUC=0.95) for subfertility |

| FLOT1 | Subfertility | Membrane trafficking | Human [21] | Part of panel (AUC=0.95) for subfertility |

| RUVBL1 | Oligoasthenozoospermia | Chromatin remodeling | Human [21] | AUC=0.93 with TFKC for oligoasthenozoospermia |

| KRT1, KRT10 | High Cryo-resilience | Structural integrity | Red Wolf [22] | Biomarkers of freeze tolerance |

Species-Specific Molecular Mechanisms

Integrative omics studies indicate that species-dependent molecular mechanisms govern male fertility [23]. Pathway enrichment analyses reveal that in bull spermatozoa, below-normal fertility is associated with enrichment in gamete production and protein biogenesis-associated pathways, while in boar spermatozoa, mitochondrial-associated metabolic pathways are enriched in normal fertility sperm [23]. This suggests that below-normal fertility in bulls may be determined by aberrant regulation of protein synthesis during spermatogenesis, whereas the modulation of reactive oxygen species generation to maintain capacitation and the acrosome reaction governs boar sperm fertility [23]. These species-specific differences highlight the importance of validating molecular biomarkers within target species, particularly in buffalo SMGT research.

Molecular and Functional Signatures of High vs. Low Fertility Sperm

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Biomarker Identification

Protocol 1: Sperm RNA Isolation and Transcriptomic Analysis

Purpose: To isolate high-quality RNA from sperm for transcriptomic profiling of fertility biomarkers.

Reagents and Equipment:

- PureSperm density gradient (Nidacon International AB) [21]

- TRIzol reagent (Ambion, Thermo Fisher Scientific) [20]

- Nanodrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) [20]

- NEB Magnetic mRNA Isolation Kit (Illumina) [20]

- NEB ultra II RNA library prep kit (Illumina) [20]

- Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencing system [20]

Procedure:

- Purify sperm using discontinuous Percoll gradient (90-45%) to eliminate contaminating somatic cells [20].

- Isolate total RNA from frozen sperm using TRIzol reagent according to manufacturer's instructions with modifications for sperm cells [20].

- Assess RNA quality and quantity using NanoDrop spectrophotometer; accept samples with 260/280 ratio of 1.7-2.0 [20].

- Enrich mRNA using NEB Magnetic mRNA Isolation Kit [20].

- Prepare transcriptome library using NEB ultra II RNA library prep kit [20].

- Sequence using Illumina NextSeq 500 paired-end technology [20].

- For validation, synthesize cDNA using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit with oligo(dT) and random hexamers [20].

- Perform quantitative PCR (qPCR) for candidate genes using appropriate reference genes for normalization.

Buffalo-Specific Modifications: For buffalo SMGT studies, include transfection with marker genes (e.g., EGFP) during protocol optimization. Use pEGFP-N1 vector propagated in DH5α competent E. coli with kanamycin/neomycin selection [3].

Protocol 2: Sperm Proteomic Profiling via LC-MS/MS

Purpose: To identify and quantify differentially abundant proteins in sperm with high and low fertility potential.

Reagents and Equipment:

- PureSperm density gradient (Nidacon International AB) [21]

- Lysis Buffer [4% SDS, 100 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6, 0.1 M DTT] [21]

- Microcon-centrifugal filter units (MRCF0R030, Merck-Millipore) [21]

- Trypsin (sequencing grade)

- C18 Stage Tips [21]

- Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry system (e.g., Q-Exactive HF, Thermo Fisher) [21]

Procedure:

- Purify sperm cells using discontinuous PureSperm density gradient to eliminate somatic cells, round cells, and leukocytes [21].

- Lyse sperm samples in Lysis Buffer and incubate at 95°C for 5 minutes [21].

- Sonicate samples on ice (10 times, 10 seconds each at 20 joules) [21].

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes and collect supernatant [21].

- Perform filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) using Microcon-centrifugal filter units [21].

- Digest proteins with trypsin (1:100 ratio) overnight at 37°C [21].

- Desalt and concentrate peptides using C18 Stage Tips [21].

- Analyze peptides by LC-MS/MS using appropriate gradients and settings [21].

- Process raw data using bioinformatics pipelines (MaxQuant, Perseus) for protein identification and quantification.

Buffalo-Specific Modifications: For buffalo sperm proteomics in SMGT applications, compare protein profiles before and after transfection procedures. Focus on membrane proteins involved in DNA uptake and proteins relevant to fertilization competence.

Protocol 3: Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer in Buffalo

Purpose: To transfer exogenous DNA into buffalo sperm for production of transgenic embryos.

Reagents and Equipment:

- pEGFP-N1 vector (BD Biosciences) [3] [6]

- Electroporation system [6]

- Dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) [3]

- Sperm-TALP medium [3]

- c-TYH medium with MBCD (for murine studies, adapt for buffalo) [12]

Procedure:

- Prepare linearized plasmid DNA (e.g., pEGFP-N1) using appropriate restriction enzymes [3].

- Thaw frozen buffalo semen at 37°C for 40 seconds [3].

- Incubate sperm solution (concentration 10^7/ml) with 3% DMSO and 20 µg/ml linearized DNA for 15 minutes at 4°C [3].

- Alternative: Use electroporation for transfection with established parameters for buffalo fetal fibroblasts [6].

- Assess transfection efficiency by EGFP expression using fluorescence microscopy [6].

- Use transfected sperm for in vitro fertilization of buffalo oocytes [3].

- Culture embryos and assess development to blastocyst stage [6].

- Validate transgene integration by Southern blot and microsatellite analysis [6].

Optimization Notes: Electroporation demonstrated higher transfection efficiency (35.5%) compared to Lipofectamine-LTX (11.7%) and X-tremeGENE (25.4%) in buffalo fetal fibroblasts [6]. The vector structure also significantly affects efficiency, with pEGFP-IRES-Neo generating more EGFP-positive colonies and higher blastocyst development rates compared to pEGFP-N1 [6].

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Sperm Molecular Profiling and SMGT

| Reagent/Solution | Application | Function | Example Product/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PureSperm Density Gradient | Sperm purification | Eliminates somatic cells and debris | PureSperm (Nidacon International AB) [21] |

| TRIzol Reagent | RNA isolation | Maintains RNA integrity during extraction | Ambion TRIzol (Thermo Fisher) [20] |

| FASP Kit | Proteomic sample prep | Filter-aided sample preparation | Microcon-centrifugal filter units [21] |

| pEGFP-N1 Vector | Transfection marker | Visual assessment of transfection efficiency | BD Biosciences #6085-1 [3] |

| MBCD | Sperm membrane manipulation | Cholesterol removal for enhanced DNA uptake | Methyl β-cyclodextrin [12] |

| DMSO | SMGT transfection | Membrane permeabilization for DNA uptake | Dimethyl sulphoxide [3] |

| c-TYH Medium | Sperm incubation | Defined medium for sperm manipulation | Choi-Toyoda-Yokoyama-Hosi medium [12] |

| Brca2-rad51-IN-1 | Brca2-rad51-IN-1, MF:C13H7BrF3N3O, MW:358.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| AChE-IN-42 | AChE-IN-42, MF:C35H43NO5, MW:557.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of proteomic and transcriptomic analyses has revealed distinct molecular hallmarks of high and low fertility sperm, including specific genes (CEP128, CSTPP1, ZNF706, CRISP2) and proteins (APOE, FN1, APCS, FLOT1) that show promise as fertility biomarkers. These molecular signatures are associated with critical sperm functions including energy metabolism, structural integrity, and fertilization capacity. Within the context of buffalo SMGT research, these molecular insights provide valuable criteria for selecting high-quality sperm for gene transfer experiments and for assessing the functional competence of transfected sperm. The experimental protocols detailed herein provide comprehensive methodologies for identifying, validating, and applying these molecular biomarkers in both basic research and applied biotechnology settings. As SMGT technologies continue to evolve in buffalo genetic improvement programs, the integration of these molecular assessments will enhance the efficiency and reproducibility of transgenic buffalo production, ultimately supporting enhanced genetic selection and breeding outcomes.

The Role of Seminal Plasma Extracellular Vesicles in Sperm Function and Gene Transfer

Seminal Plasma Extracellular Vesicles (SP-EVs) are nano-sized, lipid bilayer-enclosed vesicles secreted by the male reproductive tract, including the testis, epididymis, and accessory sex glands [24]. These vesicles facilitate critical intercellular communication by transporting bioactive molecules such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to sperm cells, thereby influencing sperm maturation, motility, capacitation, and fertilization potential [25] [26]. In the context of buffalo reproduction, SP-EVs have emerged as pivotal mediators of sperm function and promising tools for advancing sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) strategies. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for investigating SP-EVs, framed within a broader thesis on sperm-mediated gene transfer in buffalo embryo research.

SP-EVs in Buffalo Sperm Function: Key Quantitative Findings

Research in buffalo bulls has revealed significant correlations between SP-EV characteristics, molecular cargo, and sperm quality parameters. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Seasonal Impact on Sperm Quality and Oxidative Stress Markers in Egyptian Buffalo Bulls (Adapted from [1])

| Parameter | High-Quality Sperm (HQS) - Winter | High-Quality Sperm (HQS) - Summer | Low-Quality Sperm (LQS) - Winter | Low-Quality Sperm (LQS) - Summer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Motility (%) | 79.4 ± 0.65 | 69.9 ± 0.65 | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| Normal Morphology (%) | 75.5 ± 0.87 | 71.3 ± 0.87 | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| MDA (nmol/ml) | 0.71 ± 0.25 | 4.76 ± 0.18 | 2.62 ± 1.21 | 1.31 ± 1.67 |

| SOD Activity (U/ml) | 186.7 ± 0.87 | 292.0 ± 3.93 | 191.2 ± 2.88 | Not Reported |

| SP-EV CD63 Expression (%) | Lower | Not Reported | 96.08 | Not Reported |

Table 2: Proteomic and Functional Differences in SP-EVs from Buffalo Bulls of Distinct Fertility [27] [28]

| Characteristic | High Fertile (HF) Bulls | Low Fertile (LF) Bulls | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SP-EV Size | Smaller mean diameter [1] | Larger mean diameter [1] | Smaller EVs in HQS associated with better quality |

| Proteome Profile | 1,862 proteins identified [28] | 1,807 proteins identified [28] | Cargo reflects functional state |

| Differential Proteins | 87 highly abundant proteins (e.g., Protein disulfide-isomerase A4, Gelsolin) [28] | Different protein abundance patterns | Proteins involved in sperm-oocyte fusion, acrosome reaction |

| Key Pathways | Nucleosome assembly, DNA binding [28] | Altered metabolic and signaling pathways | Essential for enhancing sperm fertilizing capacity |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation and Purification of SP-EVs from Buffalo Semen

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in recent buffalo studies [27] [28] [29].

Principle: SP-EVs are isolated from seminal plasma using sequential centrifugation to remove cells and debris, followed by ultracentrifugation to pellet vesicles. Further purification is achieved via density gradient centrifugation to isolate a pure exosome population.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Iodixanol density gradient solution

- Ultracentrifuge with fixed-angle or swinging-bucket rotor

- Polycarbonate ultracentrifuge bottles/tubes

Procedure:

- Semen Collection and Seminal Plasma Separation: Collect buffalo semen using an artificial vagina. Transport to the lab at 37°C.

- Centrifuge the fresh semen at 1,520 × g for 15 minutes at 37°C to separate spermatozoa.

- Collect the supernatant (seminal plasma) and centrifuge it again at 850 × g for 5 minutes to remove any remaining cells or debris. Aliquot and store seminal plasma at -80°C if not used immediately.

- Differential Ultracentrifugation: Thaw seminal plasma on ice if frozen. Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 1 hour at 4°C to pellet large vesicles and apoptotic bodies. Retain the supernatant.

- Transfer the supernatant to polycarbonate ultracentrifuge tubes. Ultracentrifuge at 120,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C to pellet SP-EVs.

- Discard the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in a small volume of PBS.

- Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation (Purification): Layer the resuspended SP-EV pellet onto a pre-formed iodixanol density gradient (e.g., 5-40%).

- Ultracentrifuge the gradient at 120,000 × g for 16-18 hours at 4°C.

- Carefully collect the fractions containing SP-EVs (typically between 1.13-1.19 g/mL density). Dilute the collected fractions with PBS and ultracentrifuge again at 120,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C to pellet the purified SP-EVs.

- Resuspend the final SP-EV pellet in PBS. Aliquot and store at -80°C.

Quality Control: Characterize isolated SP-EVs using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for size/concentration, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphology, and Western Blotting for exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, TSG101, Alix) [27] [29].

Protocol 2: Incubation of Sperm with SP-EVs for Functional Enhancement

This protocol describes how to use isolated SP-EVs to improve sperm function, a key step for pre-treating sperm before SMGT.

Principle: Co-incubating sperm with SP-EVs from high-fertility bulls can transfer bioactive molecules that enhance sperm motility, viability, and fertilizing capacity.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Purified SP-EVs from high-fertility buffalo bulls

- Capacitation medium (e.g., Sp-TALP)

- Sperm counting chamber

Procedure:

- Sperm Preparation: Collect and evaluate fresh semen from a buffalo bull. Wash sperm by centrifugation in a suitable buffer to remove native seminal plasma.

- Co-incubation: Resuspend the sperm pellet (at a concentration of 10-20 × 10^6 sperm/mL) in capacitation medium.

- Add purified SP-EVs to the sperm suspension. The optimal concentration must be determined empirically; a starting point is 5-20 µg of SP-EV protein per 10^6 sperm [29].

- Incubate the sperm-SP-EV mixture for 45-90 minutes at 37°C under 5% CO₂.

- Post-Incubation Analysis: After incubation, assess sperm motility, viability, and other functional parameters (e.g., capacitation status, oxidative stress levels) and compare with a control sample (sperm incubated without SP-EVs).

Protocol 3: Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) Assisted by Membrane Perturbation

This protocol is adapted from principles used in murine MBCD-SMGT studies [30] and buffalo SMGT research [4], outlining a strategy to enhance foreign DNA uptake by sperm for gene transfer.

Principle: Treating sperm with cholesterol-depleting agents like Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin (MBCD) increases membrane fluidity and permeability, facilitating the uptake of exogenous DNA constructs. This treated sperm can then be used for in vitro fertilization (IVF) to produce transgenic embryos.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Sperm washing medium

- Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin (MBCD)

- Foreign DNA construct (e.g., pEGFP-N1, linearized and purified)

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) system for buffalo

Procedure:

- Sperm Preparation: Wash fresh buffalo sperm to remove seminal plasma.

- MBCD Treatment and DNA Uptake: Resuspend sperm at a concentration of 10^7 cells/mL in a medium containing a low concentration of MBCD (e.g., 0.75-2 mM) and the foreign DNA (e.g., 20 µg/mL) [4] [30].

- Incubate the mixture for 15-30 minutes at 4°C to facilitate DNA uptake without inducing excessive acrosome reaction.

- Sperm Washing: Post-incubation, wash the sperm twice by gentle centrifugation to remove excess MBCD and unbound DNA.

- In Vitro Fertilization: Use the transfected sperm for standard buffalo IVF procedures with matured oocytes.

- Validation: Screen resulting embryos for transgene integration using PCR, fluorescence (if using a reporter like GFP), or other molecular techniques.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

SP-EVs mediate their effects on sperm function through the delivery of cargo that modulates key signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms by which SP-EVs influence sperm function and facilitate gene transfer.

Diagram 1: Mechanism of SP-EV mediated sperm regulation and gene transfer. SP-EVs deliver functional cargo to sperm cells, modulating key pathways that enhance sperm function and facilitate exogenous DNA uptake for SMGT.

The molecular cargo of SP-EVs, including specific proteins and non-coding RNAs, regulates essential sperm functions through defined pathways, as detailed below.

Antioxidant Defense: SP-EVs from high-fertility buffalo bulls show elevated activity of antioxidant enzymes like Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT), and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx), which protect sperm from oxidative damage, particularly under heat stress in summer [1]. The NFE2L2-mediated pathway is a key regulator of this antioxidant response.

Capacitation and Acrosome Reaction: Proteins within SP-EVs, such as Gelsolin, are crucial for regulating the acrosome reaction [28]. Signaling pathways like cAMP and calcium signaling are modulated by EV cargo, preparing sperm for fertilization while preventing premature capacitation [27].

Sperm-Oocyte Interaction: Key proteins enriched in SP-EVs from fertile bulls, including Protein disulfide-isomerase A4, are directly implicated in the processes of sperm-zona pellucida binding and sperm-oocyte fusion [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for SP-EV and SMGT Research

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Size Exclusion Columns (e.g., qEV from Izon Science) | Isolation of SP-EVs | Gel-filtration columns that separate vesicles from contaminants based on size, preserving vesicle integrity and function [29]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-based Precipitation Kits | Isolation of SP-EVs | Kits that use water-excluding polymers to precipitate EVs out of solution; fast and suitable for processing large sample volumes [29]. |

| Antibodies against CD9, CD63, TSG101, Alix | Characterization of SP-EVs | Specific surface and intra-vesicular protein markers used in Western Blotting to confirm the identity and purity of isolated exosomes [1] [27]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) | Characterization of SP-EVs | Instrument that measures the size distribution and concentration of particles in a solution by tracking the Brownian motion of individual vesicles [27] [28]. |

| Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin (MBCD) | Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer | Cholesterol-depleting agent that increases sperm membrane permeability to facilitate the uptake of large exogenous molecules like DNA plasmids [30]. |

| Density Gradient Medium (e.g., Iodixanol) | Purification of SP-EVs | Used in ultracentrifugation to create a density barrier for the isolation of highly pure EV subpopulations away from contaminating proteins [27] [29]. |

| Hdac-IN-58 | HDAC-IN-58|Potent HDAC Inhibitor|For Research Use | HDAC-IN-58 is a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor for cancer and disease research. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

| proMMP-9 selective inhibitor-1 | proMMP-9 selective inhibitor-1, MF:C21H25FN4O2, MW:384.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Established and Novel SMGT Protocols for Buffalo Embryo Production

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) presents a promising technique for the production of transgenic livestock. This document outlines a standardized, optimized protocol for SMGT specific to Egyptian river buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). The procedure is the result of a systematic investigation to identify the optimal conditions for inserting the pEGFP-N1 gene construct into buffalo sperm, forming a critical first step in generating transgenic buffalo embryos [4] [15]. This protocol is designed to be a foundational methodology for a broader thesis on the application of assisted reproductive technologies in buffalo.

Experimental Objectives and Workflow

The primary objective of this protocol is to provide a reliable method for producing transgenic buffalo embryos using SMGT. The process involves treating sperm with exogenous DNA under specific conditions, followed by in vitro fertilization (IVF) to generate embryos that can be assessed for transgene integration.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of the standardized SMGT protocol:

Key Reagents and Materials

The following table details the essential research reagent solutions and materials required to execute this protocol successfully.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| pEGFP-N1 Plasmid | The desired gene construct used as a reporter; must be linearized prior to use [4]. |

| Dimethyl Sulphoxide (DMSO) | A transfecting agent that enhances the uptake of exogenous DNA by sperm cells [4] [7]. |

| Buffalo Sperm | Collected from donor bulls and processed to achieve a concentration of 10â· cells/ml [4]. |

| Electrolyte-Free Medium | Used for sperm incubation; can improve exogenous DNA uptake and maintain sperm motility and viability [31]. |

Optimized Protocol Parameters

The study identified optimal conditions by testing variables including plasmid DNA concentration, sperm concentration, DMSO concentration, and transfection time. The summarized optimal and tested values are presented in the table below.

Table 2: Summary of Optimized SMGT Parameters for Egyptian River Buffalo

| Parameter | Tested Conditions | Optimal Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA Concentration | Varied concentrations | 20 µg/ml of linearized pEGFP-N1 [4] |

| Sperm Concentration | Varied concentrations | 10â· cells/ml [4] |

| DMSO Concentration | Varied concentrations | 3% (v/v) [4] |

| Incubation Time | Varied durations | 15 minutes [4] |

| Incubation Temperature | - | 4°C [4] |

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

Sperm Preparation and Incubation

- Sperm Collection and Washing: Collect semen from a donor buffalo bull. Process the semen using a standard swim-up or density gradient centrifugation method to select for motile, viable sperm.

- Sperm Concentration Adjustment: Resuspend the processed sperm in an appropriate electrolyte-free medium to a final concentration of 10â· cells/ml [4].

- Complex Preparation: In the incubation medium, prepare the transfection complex containing the linearized pEGFP-N1 plasmid at a final concentration of 20 µg/ml and 3% (v/v) DMSO [4].

- Incubation: Add the prepared sperm suspension to the DNA-DMSO complex. Incubate the mixture for 15 minutes at 4°C [4].

- Post-Incubation Washing: After incubation, centrifuge the sperm sample to remove the medium containing the DNA-DMSO complex. Resuspend the sperm pellet in a clean, protein-supplemented fertilization medium in preparation for IVF.

Embryo Production and Validation

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Use the treated sperm for the in vitro fertilization of in vitro-matured buffalo oocytes (cumulus-oocyte complexes, COCs) [4].

- Embryo Culture: Culture the presumed zygotes in a suitable embryo culture medium, such as tissue culture medium (TCM199), under standard conditions (38.5°C, 5% CO2 in humidified air) [4].

- Assessment of Transgenesis: Examine the resulting embryos for the expression of the EGFP reporter gene using fluorescence microscopy. The presence of green fluorescence indicates successful transfection and transgene expression [4].

Critical Experimental Considerations

The success of this protocol hinges on adhering to the specified parameters. Deviations in DMSO concentration, incubation time, or temperature can significantly reduce transfection efficiency. Furthermore, the use of linearized, rather than circular, plasmid DNA is recommended for improved integration efficiency [4]. Researchers should note that while this protocol optimizes the production of transgenic embryos, the subsequent steps of embryo transfer and production of live transgenic offspring are complex and require additional specialized procedures, such as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) as an alternative strategy [6].

The relationship between the core SMGT protocol and its context within a broader research project is illustrated below, highlighting its role as a foundational technique.

Within the context of advancing sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) for the production of transgenic buffalo, the optimization of chemical facilitators is a critical step. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a polar aprotic solvent, has proven instrumental in enhancing the uptake of exogenous DNA by spermatozoa. This application note details the systematic optimization of DMSO for this purpose, providing a definitive protocol for its use in buffalo SMGT experiments. The content is framed within a broader thesis on buffalo embryo research, where the primary goal is to enhance the efficiency of transgenesis for improving production traits such as disease resistance, growth, and lactation performance. The protocols and data presented herein are designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in reproductive biotechnology and transgenic animal production.

DMSO Concentration Optimization for SMGT

The efficacy and cytotoxicity of DMSO are concentration-dependent. Therefore, identifying the optimal concentration that maximizes DNA uptake while minimizing adverse effects on sperm viability and subsequent embryonic development is paramount. The data below summarize key findings from empirical studies on buffalo somatic cells and spermatozoa.

Table 1: Cytotoxicity and Epigenetic Effects of DMSO on Buffalo Cells

| DMSO Concentration (%) | Exposure Duration | Effect on Cell Viability | Effect on DNA Methylation | Recommended Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | 24 hours | Minimal to no effect | No significant change | Safe for long-term exposure |

| 1% | 48 hours | Reduced viability after 48h | Increased mRNA expression of DNMT3A | Use with caution, monitor exposure |

| 2% | 48 hours | Substantial adverse effect | Significant increase in DNA methylation | Epigenotoxic, not recommended |

| 3% | 15 minutes | Minimal reduction in vitality | Not assessed in sperm | Optimal for sperm transfection |

| 4% | 24 hours | Substantial adverse effect | Hyper-methylation | Toxic, avoid use |

Table 2: Optimized DMSO Parameters for SMGT in Buffalo

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Sperm Concentration | 10 x 10^7 cells/mL | High DNA binding efficiency |

| Plasmid DNA Concentration | 20 µg/mL of linearized DNA | Successful transgene integration into the host genome |

| DMSO Concentration | 3% (v/v) | Maximum transfection efficiency with minimal sperm toxicity |

| Incubation Time | 15 minutes | Sufficient for DNA uptake |

| Incubation Temperature | 4°C | Preserves sperm vitality while facilitating DNA internalization |

Based on the synthesized data, a DMSO concentration of 3% is recommended for the transfection of buffalo spermatozoa. This concentration was empirically determined to be the most effective for enhancing the insertion of a desired gene construct (pEGFP-N1) without significantly compromising sperm vitality during a short incubation period [3]. Higher concentrations, such as 4%, induce substantial cytotoxicity and epigenotoxic effects, including increased global DNA methylation in buffalo fibroblast cells, which could compromise embryonic development [32].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for SMGT Using DMSO

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for employing DMSO as a chemical facilitator in SMGT for the production of transgenic buffalo embryos.

Reagent Preparation

- DMSO Solution: Prepare a 3% (v/v) solution of high-purity, sterile DMSO in a suitable sperm incubation medium (e.g., sperm-TALP).

- DNA Construct: Linearize the plasmid DNA (e.g., pEGFP-N1) using an appropriate restriction enzyme. Purify the linearized DNA and resuspend it in TE buffer or nuclease-free water. Determine the concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer.

- Sperm Preparation Medium: Use a modified Tyrode's medium, such as sperm-TALP, supplemented with bovine serum albumin (BSA) [3].

Sperm Transfection Procedure

- Sperm Thawing and Washing: Thaw frozen buffalo semen from a fertile bull in a 37°C water bath for 40 seconds. Layer the thawed semen onto a density gradient or wash via centrifugation in sperm-TALP medium to separate motile spermatozoa and remove the cryopreservation extender.

- Sperm Concentration Adjustment: Adjust the concentration of the motile sperm fraction to 10 x 10^7 cells/mL using fresh sperm-TALP medium.

- Incubation Mixture Preparation: In a sterile microcentrifuge tube, combine the following in order:

- Sperm suspension (10 x 10^7 cells/mL)

- Linearized plasmid DNA to a final concentration of 20 µg/mL

- DMSO to a final concentration of 3% (v/v)

- Transfection Incubation: Gently mix the solution by flicking the tube. Incubate the mixture for 15 minutes at 4°C [3].

- Washing: After incubation, centrifuge the sperm-DNA-DMSO mixture to pellet the sperm cells. Gently wash the pellet twice with fresh sperm-TALP medium to remove excess DMSO and unbound DNA.

- Viability Assessment (Optional but Recommended): Assess sperm vitality post-transfection using the one-step eosin-nigrosin staining technique. A small aliquot of transfected sperm is mixed with eosin-nigrosin stain, smeared on a slide, and examined under a microscope. Live spermatozoa remain white (eosin-impermeable), while dead spermatozoa appear pink [3].

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) and Embryo Production

- Oocyte Collection and Maturation: Collect buffalo cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) from abattoir-sourced ovaries. Aspirate follicles (2–8 mm in diameter) and select intact COCs for in vitro maturation (IVM) in TCM-199 medium supplemented with hormones (e.g., FSH, eCG) and 10% fetal calf serum for 22–24 hours at 38.5°C under 5% CO₂ [3].

- Fertilization: Use the transfected and washed spermatozoa for in vitro fertilization of the matured oocytes. Co-incubate sperm and oocytes in fertilization medium for approximately 18 hours.

- Embryo Culture: Following fertilization, wash the presumptive zygotes to remove attached sperm and cumulus cells. Culture the embryos in a sequential medium system. Assess the success of transgene integration by examining resulting embryos for the expression of the reporter gene (e.g., EGFP) under a fluorescence microscope [3].

Diagram 1: SMGT experimental workflow for transgenic buffalo embryo production.

Mechanism of Action: How DMSO Enhances DNA Uptake

DMSO facilitates DNA uptake through a combination of biophysical and biomolecular mechanisms:

- Membrane Fluidity and Permeability: DMSO interacts with phospholipid bilayers, increasing membrane fluidity. This transiently enhances the permeability of the sperm plasma membrane and nuclear envelope, allowing exogenous DNA molecules to cross more readily into the cell and nucleus [33].

- DNA Structure Modulation: Biophysical studies show that DMSO moderately decreases the bending persistence length of DNA, making it more flexible. At concentrations up to 20%, DMSO compacts DNA conformations, which may facilitate the packaging of foreign DNA within the sperm nucleus [34] [35].

- Nuclear Membrane Disruption: DMSO may act on the nuclear membrane, potentially creating temporary pores or disrupting its structure, which aids the internalization of DNA into the sperm nucleus, a key barrier in SMGT [3].

Diagram 2: Multimodal mechanism of DMSO-enhanced DNA uptake in sperm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DMSO-Mediated SMGT

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in SMGT | Exemplar Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Chemical facilitator; increases membrane permeability and DNA flexibility. | Use high-purity, sterile cell culture grade. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. |

| pEGFP-N1 Plasmid | Reporter gene construct; allows for visual screening of successful transgene integration. | Contains enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and kanamycin/neomycin resistance. |

| Sperm-TALP Medium | A defined medium for sperm capacitation, washing, and incubation during transfection. | Supports sperm viability during the DMSO exposure step. |

| Restriction Enzyme | Linearizes plasmid DNA for more efficient integration into the host genome. | e.g., AseI for pEGFP-N1; selection depends on plasmid map. |

| Eosin-Nigrosin Stain | Vital stain for assessing sperm viability post-transfection; distinguishes live/dead cells. | Quality control step to ensure transfection has not severely compromised sperm function. |

| Insecticidal agent 4 | Insecticidal agent 4, MF:C21H14Cl2F4N4O2, MW:501.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hsd17B13-IN-19 | Hsd17B13-IN-19|HSD17B13 Inhibitor|For Research | Hsd17B13-IN-19 is a potent small molecule inhibitor targeting HSD17B13 for liver disease research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Critical Considerations and Best Practices

- Cytotoxicity and Epigenotoxicity: While 3% DMSO is effective for short-term sperm transfection, be aware that even low concentrations (e.g., 0.1%) can induce large-scale transcriptomic and epigenomic changes in other cell types, including massive alterations in microRNA expression and DNA methylation patterns [33]. In buffalo fibroblasts, 2% DMSO increased DNA methylation and expression of DNMT3A [32]. These findings underscore the importance of strict concentration control and minimal exposure time.

- Solvent Purity: Always use high-purity, sterile DMSO designated for cell culture. Lower grades may contain impurities that are toxic to cells.

- Dilution Control: When adding DMSO to aqueous solutions, ensure it is mixed thoroughly but gently to avoid localized high concentrations that could damage cells.

- Quality Control: Always include appropriate controls, such as sperm incubated with DMSO but no DNA (to assess DMSO effects alone) and sperm incubated with DNA but no DMSO (to establish baseline transfection efficiency).

The application of advanced delivery systems, specifically Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanoparticles and lipid-based transfection reagents, represents a transformative approach for sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) in buffalo embryo research. Buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) are economically vital livestock, particularly in tropical regions, yet their productivity remains constrained by inherent reproductive challenges including low conception rates, seasonal anestrus, and genetic improvement limitations [36] [18]. Traditional SMGT techniques in buffaloes have relied on methods like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to facilitate exogenous DNA uptake by sperm cells, but these approaches yield inadequate DNA uptake rates and limited transgenic offspring success [4]. The unique reproductive physiology of buffaloes—characterized by inconsistent estrus expression and prolonged calving intervals—demands more efficient genetic engineering technologies to enable faster genetic progress [18].

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), particularly ZIF-8 nanoparticles, offer a promising solution to these challenges due to their porous structure, biocompatibility, and pH-responsive release properties [7]. Concurrently, lipid nanoparticle (LNP) technology has emerged as a robust platform for nucleic acid delivery, with recent demonstrations that ZIF-8 encapsulation can significantly enhance LNP transfection efficiency [37]. This application note details protocols and experimental data for leveraging these advanced delivery systems within the context of buffalo SMGT research, providing researchers with practical methodologies to overcome longstanding barriers in buffalo transgenesis.

Technical Specifications and Performance Data

Quantitative Performance of Advanced Delivery Systems

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Delivery Systems for Nucleic Acid Delivery

| Delivery System | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8 Nanoparticles | Plasmid DNA delivery to mouse sperm cells | Efficient DNA loading and delivery; Increased GFP expression in vitro | Porous structure; pH-responsive release; Low zinc ion toxicity | [7] |

| ZIF-8 encapsulated mRNA-LNPs | mRNA delivery to HEK-293 and HCT-116 cells | 3-fold (HEK-293) and 8-fold (HCT-116) increase in transfection efficiency at 48 hours | Enhanced protein expression; Protected nucleic acid integrity | [37] |

| Traditional DMSO/DNA Complex | SMGT in Egyptian river buffalo | Successful transgenic embryo production with specific parameters | Simplicity; Cost-effectiveness | [4] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 RNP Electroporation | Genome editing in buffalo zygotes | High knockout efficiency without altering embryonic developmental potential | Reduced mosaicism; Increased biallelic mutations | [38] |

Table 2: ZIF-8 Synthesis and Characterization Parameters

| Parameter | Specification | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Method | Room temperature self-assembly | Zinc nitrate and 2-methylimidazole solutions combined with stirring for 30 min, then 24 h [7] |

| Structural Characterization | FTIR peaks: 400-4000 cmâ»Â¹; XRD pattern confirmation | Confirmed zeolitic topology with 145° M-IM-M angle [7] |

| Size Distribution | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter determination under Brownian motion [7] |

| Morphology | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Regular, porous structures consistent with MOF architecture [7] |

| Sterilization | Filtration through 0.22-µm filter | Performed before incubation with sperm cells [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ZIF-8 and LNP-Based SMGT Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) | Metal precursor for ZIF-8 synthesis | 585mg dissolved in 4ml deionized water as per standard protocol [7] |

| 2-Methylimidazole | Organic linker for ZIF-8 framework | 35.11g dissolved in 40ml deionized water; molar ratio critical for porosity [7] |

| pEGFP-N1 Plasmid | Reporter gene for transfection efficiency assessment | Linearized form used at 20 µg/ml for SMGT experiments [4] |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Traditional transfection agent; comparative control | Used at 3% concentration in sperm-DNA incubation [4] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex | Genome editing in zygotes | Combined with electroporation for efficient knockout [38] |

| Puromycin | Selection antibiotic for transgenic cells | Optimal concentration: 1.5 µg/mL for buffalo fetal fibroblast selection [39] |

| RIP1 kinase inhibitor 7 | RIP1 kinase inhibitor 7, MF:C20H20FN3O, MW:337.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Doxifluridine-d3 | Doxifluridine-d3, MF:C9H11FN2O5, MW:249.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: ZIF-8 Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization

Principle: ZIF-8 nanoparticles are synthesized through self-assembly of zinc metal ions with 2-methylimidazole organic linkers, creating a porous structure ideal for nucleic acid encapsulation [7].

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 585 mg of Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O in 4 ml of deionized water. In a separate container, dissolve 35.11 g of 2-methylimidazole in 40 ml of deionized water.

- Mixing and Reaction: Combine the zinc nitrate solution with the 2-methylimidazole solution while stirring gently at room temperature. The solution will turn milky immediately upon mixing.

- Completion: Continue stirring the reaction mixture for 24 hours to ensure complete framework formation.