Toward Global Standards: A Comprehensive Framework for Standardizing Sperm Epigenetic Protocols in Clinical and Research Laboratories

The critical role of sperm epigenetics in male fertility, embryonic development, and transgenerational health is now undisputed.

Toward Global Standards: A Comprehensive Framework for Standardizing Sperm Epigenetic Protocols in Clinical and Research Laboratories

Abstract

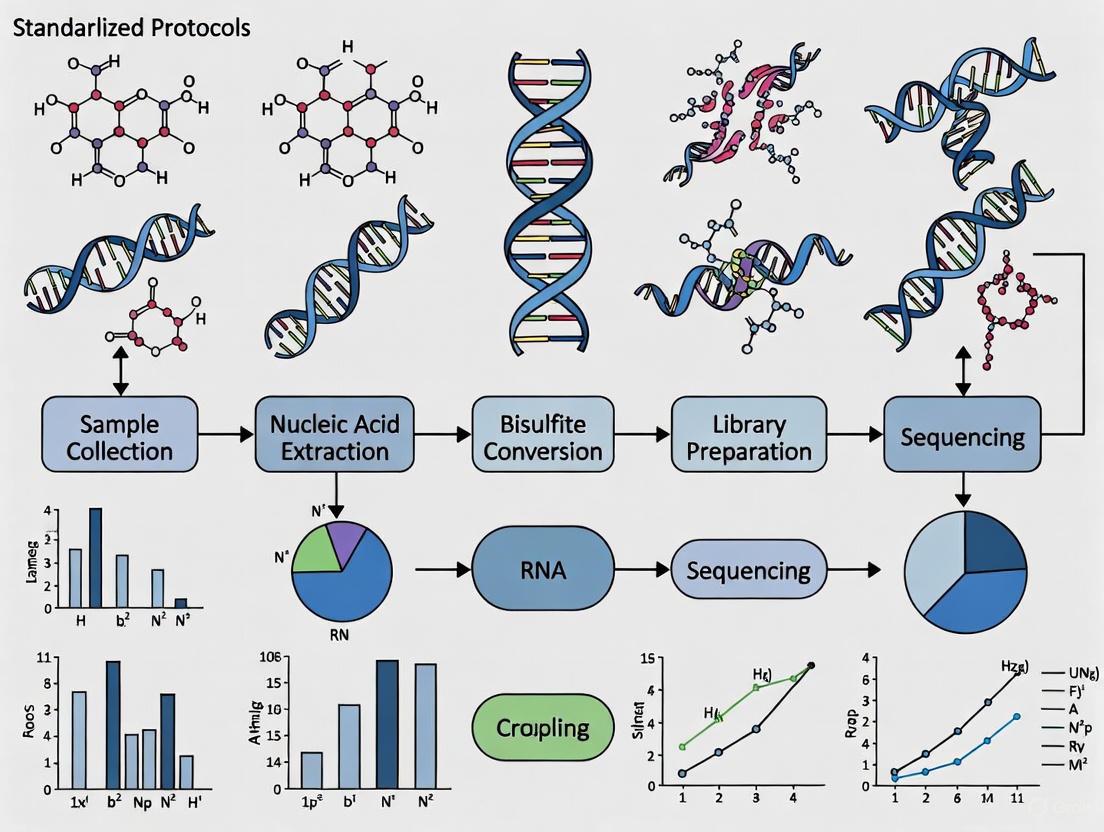

The critical role of sperm epigenetics in male fertility, embryonic development, and transgenerational health is now undisputed. However, the translation of this knowledge into clinical practice is hampered by a lack of standardized laboratory protocols. This article addresses the urgent need for harmonization by exploring the foundational principles of sperm epigenetics, proposing robust methodological pipelines for DNA methylation and sncRNA analysis, outlining strategies for troubleshooting and quality control, and establishing frameworks for multi-center validation. By providing a detailed roadmap, this work aims to bridge the gap between cutting-edge research and reliable, reproducible clinical diagnostics, ultimately improving patient care and advancing the field of reproductive medicine.

The Sperm Epigenome: Decoding its Role in Fertility and Transgenerational Inheritance

FAQ: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

FAQ 1: What are the core epigenetic mechanisms regulating spermatogenesis? Spermatogenesis is precisely controlled by at least three key epigenetic mechanisms: DNA methylation, histone modifications, and small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs). These mechanisms work synergistically to control gene expression without altering the DNA sequence, ensuring the successful development of spermatogonial stem cells into mature spermatozoa. Their proper function is critical for male fertility, and dysfunction is strongly linked to infertility [1] [2].

FAQ 2: How does DNA methylation dynamically change during spermatogenesis? DNA methylation undergoes waves of erasure and re-establishment. In mouse Primordial Germ Cells (PGCs), global DNA demethylation occurs around embryonic days 8.5 to 13.5, reducing 5mC levels to about 16.3%. De novo methylation is then re-established from E13.5 to birth. After birth, methylation levels generally increase during the transition from undifferentiated to differentiating spermatogonia, with some demethylation occurring in preleptotene spermatocytes before reaching high levels in pachytene spermatocytes [1].

FAQ 3: What are the primary functions of sperm-borne sncRNAs? Sperm-borne sncRNAs, including miRNAs, piRNAs, and tsRNAs, are no longer seen as mere byproducts. They are now recognized as crucial carriers of epigenetic information. Upon fertilization, they can influence early embryonic gene expression and are implicated in the transgenerational inheritance of paternally acquired traits, especially those influenced by environmental factors [3].

FAQ 4: Why is histone modification so important during spermiogenesis? Histone modifications are essential for the dramatic chromatin remodeling that occurs as round spermatids mature. Key modifications, such as the hyperacetylation of lysine residues on histone H4, facilitate the critical replacement of histones with protamines. This exchange is necessary for achieving the extreme nuclear compaction and DNA silencing required for producing functional sperm [4] [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: Inconsistent DNA Methylation Results in Sperm Samples

- Problem: High variability in bisulfite sequencing data from patient sperm samples.

- Solution:

- Standardized Cell Purity: Ensure pure sperm cell populations by using rigorous somatic cell lysis protocols before DNA extraction. Contamination by somatic cells (e.g., white blood cells) with different methylomes is a major confounder.

- Controlled Bisulfite Conversion: Implement a quality control step post-conversion using control oligonucleotides with known methylation status to confirm complete and non-degradative conversion.

- Batch Effect Correction: Process cases and controls in the same experimental batch. Include internal control samples (e.g., a reference sperm DNA sample) in each batch to allow for technical normalization during bioinformatic analysis [5].

Issue 2: Low Yield of sncRNAs from Mature Sperm

- Problem: Difficulty in extracting sufficient quantity and quality of sncRNAs from mature spermatozoa due to highly compacted chromatin and low cytoplasmic content.

- Solution:

- Optimized Lysis: Use a lysis buffer containing strong denaturants and reducing agents to effectively disrupt the dense, disulfide-bonded sperm nucleus and release nucleoprotein-complexed RNAs.

- DNase Treatment: Perform rigorous on-column DNase digestion to remove the vast excess of genomic DNA, which can co-purify and interfere with downstream RNA sequencing library preparation.

- Spike-in Controls: Use synthetic RNA spike-ins (e.g., from other species) during the extraction process to monitor technical efficiency and potential bias in RNA recovery [3].

Issue 3: Failure to Detect Specific Histone Modifications in Testicular Tissue

- Problem: Weak or non-specific signals in Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays for histone marks in testis samples.

- Solution:

- Antibody Validation: Use antibodies validated for ChIP-specificity in testicular tissue. Check cited literature for which antibodies have been successfully used in spermatogenic cells.

- Cross-linking Optimization: Titrate formaldehyde concentration and cross-linking time. Over-cross-linking can mask epitopes, especially in highly compacted sperm chromatin.

- Chromatin Shearing: Optimize sonication conditions to achieve fragments between 200-500 bp. The unique chromatin landscape in spermatogenic cells may require more intensive sonication than somatic cells [2].

Data Presentation: Key Epigenetic Regulators and Alterations in Male Infertility

Table 1: DNA Methylation/Demethylation Enzymes and Their Roles in Spermatogenesis

| Enzyme/Protein | Function | Consequence of Loss-of-Function in Models |

|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methyltransferase | Apoptosis of germline stem cells; Hypogonadism and meiotic arrest [1] |

| DNMT3A | De novo methyltransferase | Abnormal spermatogonial function [1] |

| DNMT3C | De novo methyltransferase | Severe defect in DSB repair and homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis [1] |

| TET1 | DNA demethylation | Fertile, but mice show a progressive decline in spermatogonia numbers [1] [4] |

Table 2: Genes with Aberrant Sperm DNA Methylation Linked to Male Infertility

| Condition | Gene Name | Methylation Status | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo-/Astheno-/ Teratozoospermia | MEST | Hypermethylation | Hydrolase activity [4] |

| DAZL | Hypermethylation | Germ cell development and differentiation [4] | |

| H19 | Hypomethylation | Imprinted gene; affects sperm concentration and motility [4] | |

| GNAS | Hypomethylation | G-protein alpha subunit [4] | |

| Non-Obstructive Azoospermia (NOA) | SOX30 | Hypermethylation | Transcription factor critical for spermatogenesis [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Human Sperm using MeDIP-Seq This protocol is based on the method used to identify epigenetic biomarkers for male infertility and FSH therapy responsiveness [6].

- Sperm Collection and DNA Extraction: Collect semen samples after 2-5 days of sexual abstinence. Purify sperm cells using a discontinuous density gradient to remove somatic cells and debris. Extract genomic DNA using a column-based kit designed for sperm cells, which often have highly cross-linked chromatin.

- DNA Fragmentation and Quality Control: Fragment the purified DNA by sonication to an average size of 200-500 bp. Verify the fragment size distribution using a bioanalyzer.

- Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP): Denature the fragmented DNA to generate single strands. Incubate with an antibody specific for 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Capture the antibody-DNA complexes using magnetic beads coated with protein A/G. Wash the beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound DNA.

- Elution and Library Preparation: Elute the immunoprecipitated methylated DNA from the beads. Prepare a next-generation sequencing library from this enriched DNA, as well as from an input DNA control (non-immunoprecipitated).

- Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis: Perform high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Illumina). Align sequences to the reference genome and use bioinformatic tools to identify Differential Methylated Regions (DMRs) between case and control samples.

Protocol 2: Investigating sncRNA Transfer via Epididymosomes This protocol helps study the post-testicular maturation of sperm sncRNA payload [3].

- Epididymosome Isolation: Dissect the caput and cauda regions of the epididymis from a model organism (e.g., mouse). Flush the luminal content or mince the tissue in a physiological buffer. Isolate epididymosomes by sequential ultracentrifugation (e.g., 10,000 x g to remove cell debris, followed by 100,000 x g to pellet vesicles).

- Sperm Collection: Collect testicular sperm from the seminiferous tubules (lacking epididymal modifications) and caput/cauda epididymal sperm.

- In Vitro Co-incubation: Incubate testicular sperm with isolated caput epididymosomes in a suitable culture medium for several hours at 34-37°C under 5% CO₂.

- RNA Extraction and Analysis: Extract total RNA from sperm before and after co-incubation. Analyze changes in the sncRNA profile using techniques like small RNA-Seq or RT-qPCR for specific sncRNAs (e.g., miRNAs, tsRNAs).

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Epigenetic Regulation of Spermatogenesis

Sperm sncRNA Acquisition Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Sperm Epigenetics Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Analysis | Bisulfite Conversion Kit, Anti-5mC Antibody, DNMT/TET Antibodies | Converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils for sequencing; Enriches methylated DNA for MeDIP; Confirms protein expression and localization via WB/IHC. |

| Histone Modification Analysis | Antibodies for H3K4me3, H3K9me3, H3K27me3, Acetyl-H4 | Key for ChIP assays to map activating/repressive histone marks genome-wide in spermatogenic cells. |

| sncRNA Analysis | Small RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit, miRNA/tsRNA Inhibitors/Mimics | Enables profiling of sperm sncRNA populations; Used for functional validation of sncRNA roles in germ cells or early embryos. |

| Cell Isolation & Culture | Percoll/Density Gradient Media, Collagenase/DNase I, SSC Culture Media | Purifies viable sperm populations; Isolates testicular cells for primary culture; Supports in vitro self-renewal and differentiation of SSCs. |

| BMY-43748 | BMY-43748, MF:C20H17F3N4O3, MW:418.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NCX899 | NCX899|NO-Releasing Enalapril Derivative | NCX899 is a nitric oxide (NO)-donating ACE inhibitor for hypertension research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Epigenetic dysregulation is increasingly recognized as a pivotal factor in male infertility, with DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling playing critical roles in spermatogenesis and early embryonic development [1]. The standardization of experimental protocols across laboratories is essential for generating reproducible and clinically meaningful data. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides, detailed methodologies, and reagent solutions to address the common challenges researchers face when investigating sperm epigenetics, thereby supporting the broader research objective of harmonizing analytical approaches in this rapidly advancing field.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Sperm Epigenetics

1. What is the clinical evidence linking DNA methylation to male infertility? Comparative analyses of testicular biopsies from patients with non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) have revealed differential expression profiles of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) compared to patients with normal spermatogenesis [1]. This dysfunction in the enzymes that establish and maintain DNA methylation patterns is strongly correlated with impaired spermatogenesis.

2. How does the sperm epigenome influence embryo development? Sperm delivers epigenetic instructions at fertilization that are required for the correct regulation of gene expression in the developing embryo. Key developmental genes in sperm lose activating marks (H3K4me2/3) and retain repressive marks (H3K27me3) during spermatid maturation. Experimental removal of these marks deregulates gene expression in the resulting embryos [7].

3. Can environmental factors alter the sperm epigenome? Yes, post-testicular oxidative stress can oxidize sperm DNA and is associated with significant changes in epigenetic marks, including an increase in overall DNA hydroxymethylation. Antioxidant supplementation can mitigate oxidative damage but may also induce mild epigenetic alterations, highlighting the need for careful clinical evaluation [8].

4. What is a "bivalent" chromatin domain, and why is it important? A bivalent chromatin domain contains both a repressive mark (H3K27me3) and an activating mark (H3K4me3) on the same promoter. In embryonic stem cells, this state poises key developmental regulators for either activation or silencing upon differentiation. A similar poising mechanism may be at work during spermatogenesis [9].

Troubleshooting Guides for Epigenetic Assays

DNA Methylation Analysis

Table 1: Troubleshooting DNA Methylation Experiments

| Problem Scenario | Expert Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Very little or no methylated DNA enrichment | When using low DNA input, strictly follow the protocol specified for that amount. MBD protein can bind non-methylated DNA to some extent if the protocol is not optimized [10]. |

| Particulate matter after adding bisulfite conversion reagent | Centrifuge the material at high speed and use only the clear supernatant for the conversion reaction [10]. |

| Poor amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA | Use primers 24-32 nts in length with no more than 2-3 mixed bases. Use a hot-start Taq polymerase (e.g., Platinum Taq) and aim for amplicons around 200 bp, as bisulfite treatment can cause strand breaks [10]. |

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

A primary challenge in ChIP is antibody specificity and efficacy, which can vary widely [9]. Always validate antibodies for your specific application. Furthermore, the homogeneity of the starting cell population is critical for clear data interpretation [9]. When working with tissues like endometrium, stratifying results based on ChIP efficiency can reveal significant, region-specific findings that are otherwise masked [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) from Tissue

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study on endometrial tissue [11].

Workflow Overview:

Methodology:

- Tissue Preparation: Snap-freeze tissue in liquid nitrogen. Pulverize the frozen tissue using a mortar and pestle.

- Cross-linking: Dissolve ~50 µg of pulverized tissue in PBS with protease inhibitors. Homogenize with a Dounce homogenizer. Cross-link proteins to DNA with formaldehyde for 10 minutes, and quench the reaction with glycine.

- Chromatin Shearing: Isolate nuclei and shear DNA to 100–300 bp fragments using a sonicator (e.g., Bioruptor).

- Immunoprecipitation: Pre-clear chromatin with non-specific IgG and magnetic A/G beads. Divide the sample into three parts:

- Input (5%): Saved for normalization.

- Specific Antibody: Incubate with antibody against your target mark (e.g., H3K27me3).

- Control IgG: Incubate with non-specific IgG. Incubate samples overnight at 4°C with rotation. Add magnetic beads the next day and incubate for 3 hours.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads sequentially with low-salt buffer, high-salt buffer, LiCl wash buffer, and TE buffer. Elute the chromatin from the beads.

- Decrosslinking and Purification: Treat the eluate with RNase A, NaCl, and proteinase K at 45°C for 2 hours to reverse cross-links. Purify the DNA using a commercial kit.

- Analysis: Quantify the enriched DNA by qPCR using primers for your regions of interest. Always include a positive control locus (e.g., MYT1 promoter) [11]. Normalize results to the input and IgG control signals.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Oxidative Stress on Sperm DNA (Mouse Model)

This protocol is adapted from a 2024 study investigating post-testicular oxidative stress [8].

Workflow Overview:

Methodology:

- Animal Model: Use transgenic mouse models susceptible to sperm DNA oxidation (e.g.,

Gpx5−/−or double knockoutsnGpx4−/−; Gpx5−/−mice). Wild-type mice serve as controls [8]. - Intervention: Administer oral antioxidant supplementation (e.g., Fertilix) via drinking water for 14 days. A control group receives no supplementation.

- Sperm Retrieval: Euthanize mice and remove the cauda epididymides. Puncture and squeeze the tissue in M2 medium. Allow sperm to disperse for 10 minutes at 37°C and count sperm using a hemocytometer.

- DNA Extraction: Centrifuge sperm and resuspend the pellet. Incubate with RNAse A, followed by Proteinase K and SDS/DTT solutions to digest RNA and proteins. Extract genomic DNA using standard phenol-chloroform methods or a commercial kit.

- Analysis:

- DNA Oxidation: Quantify the oxidized base 8-OHdG using techniques like slot blot or ELISA.

- Epigenetics: Analyze global DNA methylation (5mC) and hydroxymethylation (5hmC) levels via slot blot with specific antibodies or enzymatic assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Sperm Epigenetic Research

| Reagent / Kit | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| DNMT & TET Enzymes | Writers (DNMTs) and erasers (TETs) of DNA methylation. Critical for dynamic methylation changes during spermatogenesis [1]. |

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Highly specific antibodies (e.g., for H3K4me3, H3K27me3) are essential for ChIP assays to map histone modification landscapes [9] [11]. |

| MBD Proteins | Methyl-binding domain proteins used to enrich methylated DNA fragments from samples for downstream analysis [1] [10]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemical treatment that converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, allowing for the precise mapping of methylated cytosines via sequencing or PCR [10]. |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kits | Provide optimized buffers, beads, and protocols for efficient and specific enrichment of chromatin bound by specific proteins or histone marks [11]. |

| Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase | A hot-start polymerase recommended for robust amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA, which is notoriously difficult to PCR due to its low complexity [10]. |

| RP 70676 | RP 70676, MF:C25H28N4S, MW:416.6 g/mol |

| Rosmarinic Acid | Rosmarinic Acid|High-Purity Reference Standard |

Oxidative Stress as a Key Disruptor of Sperm Epigenetic Patterns

Male infertility is a significant global health concern, affecting approximately 8-12% of couples of childbearing age, with male factors contributing to nearly 50% of cases [12]. Oxidative stress, resulting from an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and antioxidant defenses, has emerged as a major contributor to sperm dysfunction [13] [14]. Beyond its well-documented effects on sperm motility and DNA integrity, oxidative stress disrupts the precise epigenetic programming required for normal spermatogenesis and embryogenesis [13] [15].

Sperm cells are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage due to their high polyunsaturated fatty acid content in membranes, limited cytoplasmic volume, and minimal antioxidant defenses [12]. The epigenome of spermatozoa—comprising DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA profiles—is highly susceptible to oxidative insult [13]. These epigenetic modifications can persist through fertilization and impact embryonic development, potentially contributing to transgenerational inheritance of disease susceptibility [13] [16].

Understanding the mechanisms by which oxidative stress disrupts sperm epigenetic patterns is crucial for developing standardized diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in clinical and research settings. This technical guide addresses common challenges and provides troubleshooting recommendations for researchers investigating this critical interface between oxidative stress and epigenetic regulation in male reproduction.

Core Mechanisms: How Oxidative Stress Disrupts Sperm Epigenetics

Molecular Pathways of Epigenetic Dysregulation

Excessive ROS directly targets all major epigenetic regulatory systems in spermatozoa through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

DNA Methylation Alterations: Oxidative stress induces both global hypomethylation and gene-specific hypermethylation by several mechanisms. ROS oxidize cysteine residues in DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), impairing their catalytic activity and leading to aberrant methylation patterns [13]. Additionally, oxidative base lesions like 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) interfere with DNMT binding, preventing proper maintenance of methylation patterns [12] [15]. The oxidation of methyl group donors such as S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) further disrupts methylation reactions [15].

Histone Modification Disruptions: ROS alter the activity of histone-modifying enzymes including histone acetyltransferases (HATs), histone deacetylases (HDACs), and histone methyltransferases [13]. This leads to abnormal histone acetylation and methylation patterns that compromise chromatin remodeling during spermatogenesis [13] [17]. Oxidative conditions also promote histone citrullination via peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) activation, particularly affecting histone H3 and contributing to chromatin decondensation [17].

Non-Coding RNA Dysregulation: Oxidative stress alters the expression profiles of sperm microRNAs (miRNAs) including miR-34c, miR-34b, and miR-122, which regulate critical processes such as apoptosis, sperm production, and germ cell survival [15]. These oxidative stress-induced miRNA alterations can be transmitted to the embryo during fertilization, potentially affecting early developmental programming [13] [15].

Table 1: Primary Epigenetic Alterations Induced by Oxidative Stress in Spermatozoa

| Epigenetic Mechanism | Specific Alterations | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | Global hypomethylation; Gene-specific hypermethylation (MTHFR, NTF3, IGF2, H19) | Altered genomic imprinting; Impaired spermatogenesis; Reduced embryonic viability |

| Histone Modifications | Abnormal acetylation/methylation patterns; Increased histone citrullination | Defective chromatin compaction; Disrupted protamine replacement |

| Non-coding RNA Expression | Altered miR-34c, miR-34b, miR-122, miR-449 profiles | Impaired sperm maturation; Dysregulated apoptosis; Compromised embryonic development |

Oxidative Stress Signaling and Epigenetic Disruption Pathways

The diagram below illustrates the interconnected pathways through which oxidative stress disrupts key epigenetic mechanisms in spermatozoa.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do we distinguish between oxidative stress-induced epigenetic changes versus age-related epigenetic alterations in sperm samples?

Answer: This represents a significant methodological challenge requiring careful study design and data interpretation. Paternal age independently influences sperm epigenetics through clonal selection mechanisms in spermatogonial stem cells [18] [19]. Recent research using ultra-accurate DNA sequencing (NanoSeq) has identified 40 genes where mutations are positively selected during spermatogenesis, with prevalence increasing with age [18]. To distinguish these effects:

- Implement age-matched control groups in all experiments and perform stratified analysis

- Measure and document specific oxidative stress biomarkers (8-OHdG, lipid peroxidation products, antioxidant enzyme activities) alongside epigenetic analyses

- Account for clonal expansion events by analyzing mutation patterns in addition to epigenetic marks

- Use longitudinal study designs when possible to track changes within individuals over time

Q2: What are the most reliable biomarkers for assessing oxidative stress in sperm samples?

Answer: A multi-parameter approach is recommended for comprehensive assessment:

Table 2: Biomarkers for Assessing Oxidative Stress in Sperm Samples

| Biomarker Category | Specific Markers | Methodology | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ROS Measurement | Chemiluminescence assays | Luminol-based probes | Requires fresh samples; Susceptible to interference |

| Lipid Peroxidation | Malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) | HPLC, ELISA, TBARS assay | Standardize sample processing to avoid ex vivo oxidation |

| DNA Oxidation | 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) | HPLC-MS/MS, Immunofluorescence | Correlates with DNA fragmentation and poor pregnancy outcomes |

| Protein Oxidation | Protein carbonyls, nitrotyrosine | Western blot, ELISA | Indicates advanced oxidative damage |

| Antioxidant Capacity | Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) | Colorimetric assays | Assesses overall defense status |

Q3: Why do we observe inconsistent DNA methylation patterns across different sperm samples from the same patient under similar oxidative stress conditions?

Answer: This heterogeneity arises from several sources:

- Varied susceptibility of spermatogenic stages: Different developmental stages of germ cells exhibit varying sensitivity to oxidative stress

- Clonal expansion dynamics: Mutations conferring selective advantages lead to non-random distribution of epigenetic alterations across sperm populations [18]

- Epigenetic plasticity: The epigenome undergoes active remodeling throughout spermatogenesis, creating windows of varying vulnerability

- Technical considerations: Include batch effects in processing, storage conditions affecting epigenome stability, and regional heterogeneity in epigenetic patterns within semen samples

Standardization Recommendation: Process multiple aliquots from each sample, implement rigorous quality control for bisulfite conversion efficiency in methylation studies, and use internal reference standards to normalize technical variability.

Q4: How can we minimize ex vivo oxidative damage during sperm sample processing for epigenetic analysis?

Answer: Implement a comprehensive antioxidant strategy throughout processing:

- Collection: Use antioxidant-containing collection tubes and process samples within 30 minutes of ejaculation

- Processing: Work under reduced oxygen conditions (anaerobic chambers) when possible; Use media supplemented with combined antioxidants (vitamin C, vitamin E, N-acetylcysteine)

- Cryopreservation: Include cryoprotectants with antioxidant properties; Use controlled-rate freezing to minimize ice crystal formation

- Storage: Maintain consistent temperature control; Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles; Store in aliquots to minimize oxygen exposure

Experimental Protocols: Standardized Methodologies

Comprehensive Assessment of Oxidative Stress and Epigenetic Parameters

Workflow Overview: This integrated protocol enables simultaneous assessment of oxidative stress parameters and epigenetic marks from the same sperm sample, reducing inter-sample variability.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Sample Collection and Initial Processing

- Collect semen samples after recommended 2-3 days of sexual abstinence

- Allow liquefaction for 20-30 minutes at 37°C

- Assess basic parameters (count, motility, morphology) according to WHO guidelines

- Perform sperm separation using density gradient centrifugation

- Aliquot samples for parallel oxidative stress and epigenetic analyses

Oxidative Stress Assessment

- ROS Measurement: Use chemiluminescence assay with luminol probe

- Incubate 1×10^6 sperm with 5μM luminol for 15 minutes

- Measure chemiluminescence in microplate luminometer

- Express results as relative light units (RLU)/10^6 sperm

- Lipid Peroxidation: Quantify MDA using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay

- Incubate sperm lysate with TBA reagent at 95°C for 60 minutes

- Measure fluorescence at 532nm excitation/553nm emission

- Calculate concentration using tetraethoxypropane standard curve

- DNA Oxidation: Quantify 8-OHdG by ELISA

- Extract DNA using commercial kits with antioxidant preservatives

- Use competitive ELISA with anti-8-OHdG antibody

- Express as 8-OHdG/10^5 deoxyguanosine

- ROS Measurement: Use chemiluminescence assay with luminol probe

Epigenetic Analysis

- DNA Methylation: Perform whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS)

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA

- Treat with bisulfite using commercial kits with efficiency controls

- Sequence on appropriate platform (minimum 10X coverage)

- Analyze differentially methylated regions (DMRs) bioinformatically

- Histone Modifications: Conduct chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq)

- Cross-link chromatin with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes

- Sonicate to 200-500bp fragments

- Immunoprecipitate with antibodies against specific histone marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9me3)

- Sequence immunoprecipitated DNA and input controls

- miRNA Profiling: Implement small RNA sequencing

- Extract total RNA including small fractions

- Construct libraries with adapters for small RNAs

- Sequence on appropriate platform

- Quantify known miRNAs and identify novel species

- DNA Methylation: Perform whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS)

Intervention Studies: Antioxidant Supplementation Protocol

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of antioxidant interventions in reversing oxidative stress-induced epigenetic alterations.

Experimental Design:

- Duration: 3-month intervention period based on established spermatogenesis cycles

- Groups: Randomized, placebo-controlled design with pre- and post-intervention sampling

- Participants: Men with confirmed oxidative stress (elevated ROS and DNA fragmentation)

Antioxidant Formulation:

- Vitamin C: 1000mg/day

- Vitamin E: 800IU/day

- N-acetylcysteine: 600mg/day

- Coenzyme Q10: 200mg/day

- Zinc: 50mg/day

Assessment Timeline:

- Baseline assessment (epigenetic, oxidative stress, conventional semen parameters)

- Monthly follow-up for adherence and safety monitoring

- Endpoint assessment (3 months) repeating baseline measurements

- Optional extended follow-up for persistence assessment

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Investigation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Oxidative Stress and Sperm Epigenetics

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ROS Detection | Luminol, DCFDA, MitoSOX Red | MitoSOX specifically detects mitochondrial superoxide; Validate with positive controls |

| Oxidative Damage Kits | OxiSelect TBARS Assay, 8-OHdG ELISA | Include internal standards; Run in duplicate |

| DNA Methylation | EZ DNA Methylation kits, NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq | Bisulfite conversion efficiency >99% required |

| Histone Modification | Active Motif ChIP kits, specific antibodies (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) | Verify antibody specificity with peptide blocks |

| miRNA Analysis | Qiagen miRNeasy, Illumina Small RNA Library Prep | Include spike-in controls for normalization |

| Antioxidants | N-acetylcysteine, Vitamin E (Trolox), MitoTEMPO | Use fresh preparations; Protect from light |

| Sperm Processing | SpermGrad, Human Tubal Fluid media | Use protein-supplemented media for processing |

Data Interpretation Guidelines: Standards for Analysis and Reporting

Quality Control Thresholds

Establish and report the following quality metrics for all experiments:

- Sample purity: >95% sperm cells in final analysis

- DNA integrity: DNA fragmentation index <30% for epigenetic studies

- Bisulfite conversion efficiency: >99% for methylation analyses

- Sequencing depth: Minimum 10X coverage for WGBS, 20 million reads for ChIP-seq

- Antioxidant validation: Include positive and negative controls in all oxidative stress assays

Statistical Considerations

- Account for multiple testing in epigenome-wide analyses (FDR <0.05)

- Include appropriate covariates in models (age, BMI, abstinence time)

- Report effect sizes alongside p-values for interventional studies

- For paired designs (pre-post intervention), use appropriate paired statistical tests

Standardizing methodologies for investigating oxidative stress-induced epigenetic disruptions in sperm is essential for generating comparable, reproducible data across laboratories. This technical guide provides a framework for comprehensive assessment, troubleshooting common challenges, and implementing rigorous experimental protocols. As research in this field advances, continued refinement of these standards will enhance our understanding of how oxidative stress compromises sperm epigenetic integrity and ultimately affects reproductive outcomes and intergenerational health.

For decades, the primary focus of developmental origins of health and disease has centered on maternal influences. However, a growing body of evidence demonstrates that paternal life experiences before conception significantly impact offspring health and development through epigenetic mechanisms [20] [21]. The paternal environment—including diet, stress, toxin exposure, and lifestyle choices—can induce epigenetic modifications in sperm that are transmitted to the embryo, potentially influencing metabolic function, neurodevelopment, and disease susceptibility in subsequent generations [22]. This technical support center addresses the critical need for standardized methodologies in the rapidly evolving field of paternal epigenetic inheritance research, providing troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to enhance reproducibility across laboratories.

Key Epigenetic Mechanisms in Paternal Inheritance

Sperm Epigenetic Landscape

Sperm possess a unique epigenome characterized by several distinct features that enable the transmission of paternal environmental information to the embryo. Key epigenetic marks in sperm include:

DNA Methylation: Cytosine methylation at CpG islands regulates gene expression and genomic imprinting [20]. Although most methylation marks are erased during embryonic reprogramming, some regions, particularly imprinted genes and transposable elements, can escape this process [23] [24].

Histone Modifications: During spermatogenesis, most histones are replaced by protamines to achieve highly compact chromatin [20]. However, approximately 5%-15% of histones are retained at specific genomic regions, particularly promoters of developmentally important genes [20] [7]. These histones carry modifications such as H3K4me2/3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me that can influence embryonic gene expression [7].

Non-coding RNAs: Sperm contain various non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs), and rRNA-derived small RNAs (rsRNAs) [22] [24]. These RNAs can directly influence embryonic development and mediate the transmission of paternal environmental exposures [22] [24].

Evading Embryonic Reprogramming

A significant challenge in understanding paternal epigenetic inheritance involves how sperm epigenetic marks evade the extensive reprogramming that occurs after fertilization. Research indicates that some epigenetic marks escape this reprogramming through:

- Erasure and Reestablishment: Some paternal epigenetic marks are erased during embryonic reprogramming but are subsequently reestablished during later developmental stages [24].

- Resistance to Erasure: Certain genomic regions, particularly imprinted genes and some transposable elements, demonstrate resistance to demethylation during reprogramming [23].

Studies investigating paternal stress exposure have shown that approximately 11.36% of differential DNA methylation regions (DMRs) in sperm demonstrate intergenerational inheritance, while 0.48% show transgenerational inheritance, persisting even to the F2 generation [24].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Standardized Paternal Exposure Models

Several well-established experimental models are used to study paternal epigenetic inheritance:

Dietary Manipulation Models:

- High-Fat Diet (HFD): Typically 60% fat content administered for 8-12 weeks before mating [25]

- Low-Protein Diet: Usually 5-10% protein content for multiple generations [21]

- Methyl-Donor Supplementation: Folate, choline, betaine, and vitamin B12 [21]

Psychological Stress Models:

- Restraint Stress: Physical restriction for 2-6 hours daily over several weeks [24]

- Chronic Unpredictable Stress: Variable stressors applied unpredictably to prevent habituation [22]

Toxicant Exposure Models:

- Endocrine Disruptors: Bisphenol A, phthalates administered via drinking water [20] [22]

- Heavy Metals: Cadmium, lead exposure studies [22]

- Air Pollutants: PM2.5 exposure systems [22]

Quantitative Data on Paternal Exposure Effects

Table 1: Paternal Exposure Effects on Offspring Health Outcomes

| Paternal Exposure | Experimental Model | Offspring Phenotypes | Epigenetic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fat Diet [21] [25] | Mouse (C57BL/6) | Glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, increased body weight, altered lipid metabolism | Sperm DNA methylation changes, altered sncRNA expression (miRNA, tsRNA), H3K4me3 alterations |

| Psychological Stress [24] | Mouse (restraint stress) | Depressive-like behaviors, metabolic disorders, reproductive deficits | Differential DNA methylation regions (DMRs), tsRNA and rsRNA dysregulation |

| Protein Restriction [21] | Mouse (low protein diet) | Impaired cardiovascular function, altered lipid metabolism, perturbed placental development | Modified DNA methylation, histone modifications, altered expression of imprinted genes |

| Endocrine Disruptors [20] [22] | Human cohorts & rodent models | Blastocyst quality reduction, reproductive abnormalities, metabolic changes | Altered DNA methylation in sperm, particularly at imprinted genes |

Table 2: Inheritance Patterns of Paternal Epigenetic Modifications

| Epigenetic Mark | Intergenerational Inheritance | Transgenerational Inheritance | Reprogramming Evasion Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation [24] | ~11.36% of stress-induced DMRs | ~0.48% of stress-induced DMRs | Erasure and subsequent reestablishment |

| Histone Modifications [7] | Retained at developmental promoters | Limited evidence | Protection during histone-to-protamine transition |

| tsRNAs/miRNAs [22] [24] | Altered expression in F1 | Limited evidence | Direct delivery to oocyte during fertilization |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Sperm Epigenetic Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Analysis Kits | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing kits, ChIP-seq kits, MeDIP kits | Genome-wide methylation mapping, histone modification profiling |

| sncRNA Analysis Tools | Small RNA sequencing kits, tsRNA-enrichment protocols, miRNA inhibitors | sncRNA profiling and functional validation |

| Antibodies | Anti-5-methylcytosine, anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K27me3, anti-H3K9me2 | Immunofluorescence, Western blot, chromatin immunoprecipitation |

| Sperm Processing Reagents | Protamine extraction buffers, histone purification kits, sperm lysis buffers | Sperm epigenetic mark isolation and analysis |

| Embryo Culture Media | KSOM, M16, specialized methyl donor-supplemented media | In vitro fertilization and preimplantation embryo culture |

| Necrostatin 2 racemate | Necrostatin 2 racemate, MF:C13H12ClN3O2, MW:277.70 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fluacrypyrim |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Q1: We observe high variability in offspring phenotypes despite controlled paternal exposures. What factors might contribute to this inconsistency?

A: Several factors can contribute to phenotypic variability:

- Strain-specific effects: C57BL/6 mice show different susceptibility to paternal diet effects compared to other strains [25]. Consistently use the same genetic background.

- Exposure timing and duration: The same stressor applied during different developmental windows (early life vs. adulthood) produces distinct epigenetic outcomes [20]. Standardize exposure protocols.

- Sperm heterogeneity: Use pooled sperm from multiple animals for epigenomic analyses to minimize individual variation.

- Maternal environment: Even when using control females, subtle variations in maternal care can influence offspring phenotypes. Cross-foster pups to control for this effect.

Q2: Our analyses detect only weak epigenetic signals in offspring tissues despite strong paternal exposure effects. How can we enhance detection sensitivity?

A: This common challenge arises because only a small proportion of paternal epigenetic marks evade reprogramming:

- Focus on resilient genomic regions: Prioritize analysis of imprinted genes, transposable elements, and metastable epialleles known to resist reprogramming [23] [24].

- Increase sequencing depth: For bisulfite sequencing, aim for >20X coverage to detect subtle methylation changes [24].

- Analyze multiple offspring: Pool data from multiple F1 individuals to identify consistently altered regions.

- Use targeted approaches: Instead of whole-genome analyses, focus on candidate regions identified in prior studies of similar exposures.

Q3: How can we distinguish true transgenerational inheritance from intergenerational effects?

A: Proper experimental design is critical:

- For paternal lineage studies: True transgenerational inheritance requires effects persisting in the F2 generation (great-grandchildren of exposed males), as the F1 generation (grandchildren) were directly exposed as germ cells within the F0 father [24].

- Include proper controls: Always compare against non-exposed control lineages maintained in parallel for the same number of generations.

- Track specific epigenetic marks: Use bisulfite sequencing or other epigenetic methods to confirm transmission of specific marks across generations [24].

Technical Methodology FAQs

Q4: What is the optimal method for isolating high-quality sperm for epigenetic analysis?

A: Standardized sperm isolation is crucial for reproducible results:

- Collection method: Use swim-up or density gradient centrifugation to isolate motile sperm and minimize somatic cell contamination.

- Processing time: Process samples within 2 hours of collection to prevent degradation of epigenetic marks.

- Storage conditions: Snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C for DNA/RNA analyses; use cross-linking for histone studies.

- Quality assessment: Assess sperm viability, motility, and morphology before epigenetic analysis to control for sample quality.

Q5: Which epigenetic analysis platform provides the best balance between coverage and cost for sperm studies?

A: Platform selection depends on research goals and resources:

- Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS): Cost-effective for CpG-rich regions, suitable for initial screening.

- Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS): Comprehensive coverage but more expensive; recommended for discovery-phase studies [24].

- EPIC array: Targeted approach for human studies covering >850,000 CpG sites.

- Small RNA sequencing: Essential for sncRNA profiling; requires specialized library preparation protocols for tsRNAs [22].

Q6: How can we control for potential maternal contributions in paternal inheritance studies?

A: Several strategies can help control for maternal effects:

- Use virgin control females: Ensure females have no prior mating experience or pregnancies.

- Standardize maternal environment: House all females under identical conditions before and during mating.

- Cross-fostering: Transfer pups to unaffected foster mothers immediately after birth to control for postnatal maternal effects.

- In vitro fertilization: Use IVF to completely control the maternal contribution during conception [7].

Standardization and Future Directions

The field of paternal epigenetic inheritance requires rigorous standardization to enhance reproducibility. Key considerations include:

- Reporting standards: Clearly document exposure paradigms, animal housing conditions, sperm collection methods, and analysis parameters.

- Epigenetic controls: Include reference samples in epigenetic analyses to control for technical batch effects.

- Multidimensional analysis: Integrate data from multiple epigenetic layers (DNA methylation, histone modifications, and sncRNAs) rather than focusing on single mechanisms.

- Replication across models: Validate findings in multiple experimental systems and, when possible, human cohorts.

As research progresses, standardized protocols for sperm epigenetic analysis will be essential for understanding the mechanisms underlying paternal inheritance and developing potential interventions to mitigate adverse transgenerational health effects.

The Impact of Paternal Age and Environmental Exposures on Sperm Epigenetic Integrity

Sperm epigenetics refers to the molecular modifications on sperm DNA that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These modifications include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and the presence of small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) [26]. The sperm epigenome is established during germ cell development and maturation and is crucial for proper sperm function, fertilization, and embryonic development [26]. Unlike female eggs, which are formed before birth, sperm are produced continuously throughout a man's post-pubertal life, making the sperm epigenome uniquely susceptible to modification by age and environmental exposures [27].

Key Sperm Epigenetic Modifications and Their Functions

Table 1: Core Components of the Sperm Epigenome

| Epigenetic Mark | Primary Function in Sperm | Impact on Offspring Health |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | Gene regulation, genomic imprinting, transposon silencing [26]. | Altered patterns linked to impaired embryo development and diseases like Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome [26]. |

| Histone Modification | Chromatin compaction during protamination; retention at developmental gene promoters [26]. | Post-translational modifications can prevent proper histone removal, affecting genome programming [26]. |

| Small Non-Coding RNAs | Post-transcriptional gene regulation; potential role in intergenerational communication [26]. | Associated with transmission of paternal stress responses and metabolic phenotypes [26]. |

Impact of Paternal Age on Sperm Epigenetics

Increasing paternal age is associated with measurable declines in conventional sperm quality and integrity. Studies involving large cohorts have demonstrated that advancing age correlates with decreased semen volume, sperm motility, and increased sperm DNA fragmentation [28].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Paternal Age on Sperm Parameters (Data from [28])

| Paternal Age Group | Semen Volume | Progressive Motility | Total Motility | Sperm DNA Fragmentation Index (DFI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-24 years | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Lowest |

| 25-29 years | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 30-34 years | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 35-39 years | Significant decline | Significant decline | Significant decline | Increased |

| >40 years | Lowest | Lowest | Lowest | Highest |

Beyond DNA fragmentation, aging also affects the sperm epigenome. The Paternal Age Effect (PAE) describes the accumulation of de novo mutations and epigenetic changes over time, increasing the risk of certain genetic syndromes and complex disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in offspring [27]. While sperm banks often set donor age limits at 40, the specific age thresholds for significant risk remain less defined than those for maternal age [27].

Impact of Environmental Exposures and Lifestyle on Sperm Epigenetics

Paternal lifestyle and environmental factors before conception can significantly alter the sperm epigenome, potentially affecting offspring health via epigenetic inheritance [26]. Key exposures include:

- Smoking: Induces DNA hypermethylation in genes related to anti-oxidation and insulin resistance [26].

- Obesity and Diet: Associated with greater risks of metabolic dysfunction (e.g., high blood glucose, increased body weight) in offspring via epigenetic alterations in sperm [26].

- Chronic Stress: Linked to metabolic changes and increased risk of depressive-like behavior and sensitivity to stress in offspring [26].

- Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs): Paternal exposure is linked to transgenerational transmission of increased disease predisposition, including infertility, testicular disorders, and obesity [26].

- Alcohol Consumption: Impacts the success of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) and can modify the sperm epigenome [26].

These factors can cause epimutations—heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve changes to the underlying DNA sequence. Some of these altered epigenetic marks can escape the widespread reprogramming that occurs after fertilization, allowing for potential intergenerational or transgenerational inheritance [29] [26].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Sperm Epigenetic Research

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Somatic Cell Lysis Buffer (SCLB) | Selectively lyses contaminating somatic cells in semen samples [30]. | Purification of sperm population for downstream epigenetic analysis (e.g., DNA methylation). |

| Infinium Methylation BeadChip | Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation at specific CpG sites [30]. | Profiling methylome; identifying somatic contamination using specific CpG markers. |

| Antibodies (e.g., 5-mdC) | Immunodetection of specific epigenetic marks, like 5-methylcytosine [31]. | ELISA-based global methylation quantification; immunoprecipitation for sequencing. |

| Enzymes (DNMTs, TETs) | Catalyze DNA methylation (DNMTs) and active demethylation (TETs) [26]. | In vitro studies to manipulate or understand the establishment/removal of methylation. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagents | Chemical treatment that converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil, leaving methylated cytosine unchanged [31]. | Foundation for bisulfite sequencing to map DNA methylation at single-base resolution. |

| Protamine-Specific Stains | Assess the efficiency of histone-to-protamine exchange during spermiogenesis [26]. | Evaluation of sperm chromatin maturity and packaging quality. |

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and Critical Protocols

Protocol: Sperm Purification and Somatic Cell Contamination Control

Objective: To obtain a highly pure sperm population for epigenetic analysis, free from somatic cell contamination that can skew results [30].

- Initial Inspection: Wash fresh semen sample twice with 1X PBS by centrifugation at 200 g for 15 min at 4°C. Inspect the sample under a microscope (e.g., 20X objective) to identify the level of somatic cell contamination and perform a sperm count.

- Somatic Cell Lysis: Incubate the washed sample with freshly prepared Somatic Cell Lysis Buffer (SCLB) (0.1% SDS, 0.5% Triton X-100 in ddH2O) for 30 min at 4°C [30].

- Post-Lysis Inspection: Re-examine the sample under a microscope. If somatic cells are still detected, pellet the sample by centrifugation and repeat the SCLB treatment.

- Final Pellet: After confirming the absence of somatic cells, pellet the purified sperm by centrifugation, followed by a final PBS wash.

- Quality Control Checkpoints:

- Microscopy: Visual confirmation of somatic cell removal.

- Biomarker Analysis: Analyze DNA methylation at predefined CpG sites known to be highly methylated in somatic cells but hypomethylated in sperm (e.g., the 9,564 CpG sites identified by [30]). This serves as a molecular confirmation of purity.

- Data Analysis Cut-off: During differential methylation analysis, apply a conservative cut-off (e.g., 15%) to filter out potential bias from residual, undetectable contamination [30].

Protocol: Assessing Sperm DNA Fragmentation (SDF)

Objective: To evaluate the level of DNA damage in a sperm sample, a key parameter of male fertility and gamete quality [32] [33].

Multiple tests are available, each with strengths and limitations. The choice of test should be guided by the clinical question and laboratory capabilities [33].

Table 4: Common Sperm DNA Fragmentation (SDF) Tests

| Test Name | Methodology Principle | Key Metrics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUNEL Assay [33] | Labels DNA strand breaks with fluorescent dUTP via terminal transferase. | % of TUNEL-positive sperm. | Direct measurement; can use flow cytometry or microscopy; suitable for low sperm counts. | High inter-laboratory variability; relatively expensive. |

| SCSA [33] | Measures DNA denaturation susceptibility using acridine orange stain. | DNA Fragmentation Index (DFI); High DNA Stainability (HDS). | High reproducibility; analysis of large cell numbers; sample can be frozen. | Requires expensive flow cytometer; requires high sperm concentration. |

| Comet Assay [33] | Electrophoresis-based visualization of DNA fragments. | Tail length, intensity, and moment. | Sensitive; can distinguish single vs. double-strand breaks; affordable. | Protocol not standardized; low throughput; potential for subjective analysis. |

| SCD Assay [33] | Acid denaturation and removal of nuclear proteins to reveal halo patterns. | Halo size (large halo = low fragmentation). | Simple, quick, economical; no complex instruments needed. | Halo can be difficult to score; sperm tail is not preserved. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: Our sperm DNA methylation data from oligozoospermic samples shows widespread hypermethylation. How can we be sure this is a real biological signal and not an artifact from somatic cell contamination?

A: Somatic cell contamination is a major confounder, especially in samples with low sperm counts [30]. Implement a multi-layered quality control strategy:

- Rigorous Wet-Lab Purification: Always include a Somatic Cell Lysis Buffer (SCLB) treatment step in your sample processing protocol and confirm its efficacy under a microscope [30].

- Molecular QC: After DNA extraction, probe a panel of pre-identified CpG sites that are hypermethylated in blood/somatic cells but hypomethylated in pure sperm. A high signal in these markers indicates persistent contamination [30].

- Statistical Safeguard: During data analysis, apply a stringent differential methylation cut-off (e.g., ≥15-20%). This helps filter out spurious signals arising from low-level contamination that evades visual detection [30].

Q2: Which Sperm DNA Fragmentation (SDF) test should I implement in my clinical laboratory?

A: There is no single "best" test; the choice depends on your clinical goals and resources [33].

- For high-throughput, standardized testing with high reproducibility, the SCSA is a strong choice, though it requires a flow cytometer [33].

- For a direct, measurable test that can be used on very low sperm counts (e.g., from testicular biopsies), the TUNEL assay is advantageous [33].

- For a cost-effective and relatively simple method, the SCD (Halo) test is widely used in andrology labs [33].

- Consider the predictive value you need: TUNEL and the alkaline comet assay directly measure DNA breaks and may show closer correlations with ART outcomes [33].

Q3: How long can we store sperm for research purposes before the epigenome is significantly compromised?

A: Emerging evidence indicates that even short-term storage can induce epigenetic changes. A study on common carp sperm showed that 14 days of in vitro storage led to reduced sperm motility, increased DNA fragmentation, and altered DNA methylation patterns in both the sperm and the resulting offspring [31]. These changes were associated with functional alterations in the progeny, including impaired cardiac performance [31]. While optimized storage media can maintain fertilization capacity, researchers should be aware that storage duration itself is an experimental variable that can influence the sperm epigenome. It is critical to standardize and minimize storage times across experimental groups.

Q4: To what extent do paternal lifestyle-induced epigenetic changes get erased after fertilization and actually impact the offspring?

A: This is an active area of research. While a global epigenetic reprogramming occurs after fertilization, some epigenetic marks, particularly at imprinted gene control regions and certain transposable elements, can escape this erasure [26]. Furthermore, sperm carry small non-coding RNAs and retained histones with specific modifications that can influence gene expression in the early embryo [26]. Paternal exposure to factors like obesity, stress, or toxins can alter these marks, and studies in animal models have shown these changes can be associated with metabolic and behavioral phenotypes in the next generation [26]. The inheritance is likely probabilistic and context-dependent, not absolute.

Building a Robust Pipeline: From Sample Collection to Data Generation

Standard Operating Procedures for Sperm Collection, Processing, and Storage

Pre-Collection Procedures and Patient Preparation

Abstinence Period: Maintain sexual abstinence for two to seven days before sample collection. Record the date of the last ejaculation, as this information is critical for interpreting concentration and motility results. An abstinence period of less than two days can lower sperm count, while more than seven days can increase the proportion of immobile or degraded sperm [34].

Lifestyle and Environmental Factors: Patients should limit or avoid alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drugs for several days to a week before collection, as these substances are linked to reduced sperm quality. It is also crucial to avoid heat exposure to the testicles (e.g., hot tubs, saunas, tight underwear) in the 48 to 72 hours before collection. Patients should postpone collection if they have a fever or active infection, as illness can temporarily alter semen parameters [34].

Sample Identification and Documentation: Before collection, ensure all necessary materials are present, including a sterile collection cup, labels, and required paperwork. Proper patient identification and accurate documentation are essential for traceability and preventing sample mix-ups [35].

Sample Collection Protocols

Collection Method: The complete ejaculate must be collected directly into the sterile container provided by the clinic or laboratory. Using any other container, such as household jars, is prohibited. The inside of the cup or lid should not be touched, as this can introduce contaminants. The initial fraction of the ejaculate often contains the highest sperm concentration, so collecting the full sample is critical for accurate analysis [34].

Collection Environment: For at-home collection, the sample should be produced in a clean, private environment to minimize contamination risk. Lubricants, soaps, or oils should not be used during collection unless a special sperm-safe product is supplied by the clinic [34].

Transport and Temperature Control: The sealed specimen must be maintained at room or body temperature (20–37°C) during transport. The sample should be delivered to the laboratory promptly; a time frame of 30 to 60 minutes from collection to delivery is recommended to maintain sperm motility and viability for analysis [34].

Semen Processing and Cryopreservation

Fundamentals of Cryopreservation

Cryopreservation is a routine technique in assisted reproduction to preserve male genetic material for decades. The process involves several key steps: the addition of cryoprotective agents (CPAs), cooling to storage temperature in liquid nitrogen (-196°C), thawing, and removal of the CPA. The primary goal is to achieve the highest post-thaw cell survival rate possible [36].

Table 1: Common Cryopreservation Techniques for Human Spermatozoa

| Technique | Cooling Rate | Key Principles | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programmable Slow Freezing | 0.5°C/min to 0°C/min | Controlled, gradual temperature drop allows for cellular dehydration, minimizing intracellular ice crystal formation [36]. | Most commonly used technique [36]. |

| Freezing on Liquid Nitrogen Vapors | Rapid, but uncontrolled | Sample is placed in the vapors above liquid nitrogen before immersion. Simpler than programmable freezing [36]. | A common rapid freezing method. |

| Vitrification (Ultrarapid Freezing) | Hundreds to thousands of °C/min | Extremely high cooling rates solidify the solution into a glass-like state without ice crystals [36]. | Not yet universally accepted as clinically relevant for sperm [36]. |

Cryoprotectants and Additives

Cryoprotective agents (CPAs) are essential to reduce cryodamage caused by freezing and thawing.

- Permeable CPAs: These include glycerol, DMSO, ethylene glycol, and 1,2-propanediol. They cross the cell membrane and facilitate water movement out of the cell, preventing the formation of lethal intracellular ice [36].

- Non-Permeable CPAs: These include sucrose, trehalose, and glucose. They increase the osmotic pressure outside the cell, drawing water out and promoting dehydration [36]. Antioxidants are sometimes added in clinical trials to mitigate oxidative stress and potentially improve post-thaw sperm quality [36].

Laboratory Standards and Staffing

Laboratories performing andrology procedures must adhere to strict standards. In the United States, laboratories performing quantitative semen analysis must comply with Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) regulations and are typically registered as high-complexity laboratories [35]. Accreditation by bodies such as the College of American Pathologists (CAP) or The Joint Commission (TJC) is required for embryology laboratories in clinics that are members of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) [35].

Personnel requirements are also specified, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Minimum Staff Requirements for an Embryology Laboratory (Adapted from ASRM Guidelines) [35]

| Title | Minimum Education | Minimum Experience | Continuing Education |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Supervisor | Bachelor's degree in a chemical, physical, or biological science | 4 years (with BS/BA) | 24 hours every 2 years |

| Senior Embryologist | Bachelor's degree in a chemical, physical, or biological science | 3 years | 24 hours every 2 years |

| Embryologist | Bachelor's degree in a chemical, physical, or biological science | 2 years | 24 hours every 2 years |

Potential Cryodamage and Molecular Impacts

The process of cryopreservation generates structural and molecular alterations in spermatozoa, known collectively as cryodamage. Injuries occur due to oxidative, temperature, and osmotic stress, leading to [36]:

- Decreases in sperm motility and viability.

- Reductions in mitochondrial activity.

- Increases in DNA fragmentation (DNA integrity damage).

- Changes in the fluidity and integrity of the plasma membrane.

The plasma membrane, rich in fatty acids, is the primary site of cryoinjury. Temperature stress during freezing and thawing causes irreversible changes to membrane lipids and proteins, leading to a loss of membrane fluidity and barrier function [36].

Epigenetic Considerations in Sperm Processing

Beyond genetic material, sperm carry epigenetic information that can influence embryonic development. The sperm epigenome includes chromatin modifications, DNA methylation, and non-coding RNAs [37]. During spermiogenesis, most histones are replaced by protamines to compact the DNA, but ~1% of histones in mice and up to 15% in humans are retained at specific genomic locations [37]. These retained histones often bear modifications like H3K4me3 and are enriched at promoters of genes critical for embryonic development [37].

Processing and cryopreservation can potentially impact these delicate epigenetic marks. Therefore, standardizing protocols is essential not only for preserving sperm motility and viability but also for maintaining the integrity of the paternal epigenetic template, which is programmed to regulate gene expression in the resulting embryo [7] [37].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Sperm Cryopreservation Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Permeable Cryoprotectants | Cross the cell membrane to depress freezing point and prevent intracellular ice formation [36]. | Glycerol, DMSO, Ethylene Glycol, 1,2-Propanediol. |

| Non-Permeable Cryoprotectants | Increase extracellular osmotic pressure, promoting cellular dehydration [36]. | Sucrose, Trehalose, Glucose. |

| Antioxidants | Mitigate oxidative stress during processing and freezing that can damage sperm membranes and DNA [36]. | Varied; often used in clinical trials. Specific compounds not listed in results. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Provides ultra-low temperature environment (-196°C) for long-term storage of cryopreserved samples [36]. | Used for storage and as a coolant in vapor freezing methods. |

| Sterile Collection Cups | Ensure aseptic collection of semen sample to prevent microbial contamination [34]. | Must be provided by the clinic/lab; household containers are not acceptable. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: What are the most common causes of poor post-thaw sperm motility, and how can they be addressed?

- Cause: Improper cooling rates during freezing. Rates that are too fast lead to intracellular ice formation, while rates that are too slow cause excessive dehydration and osmotic stress [36].

- Solution: Ensure the cryopreservation equipment is properly calibrated and that standardized protocols for slow freezing or vitrification are strictly followed. Optimizing the type and concentration of cryoprotectants can also help [36].

Q2: We are seeing high levels of DNA fragmentation in post-thaw samples. What could be the source of this?

- Cause: Cryopreservation-induced oxidative stress is a major factor leading to DNA damage [36].

- Solution: Consider the addition of antioxidants to the cryopreservation medium. Furthermore, review the processing steps to minimize physical and oxidative stress before the freezing procedure begins.

Q3: A patient's at-home collected sample arrived at the lab after 90 minutes. What is the impact, and should we process it?

- Impact: Sperm motility and viability progressively decline after collection. A 90-minute delay likely significantly reduces motility, compromising the analysis or usability for assisted reproductive technologies [34].

- Action: Process the sample but document the delay thoroughly on the report. The results should be interpreted with caution. For clinical use, discuss the potential impact with the physician and patient. Emphasize the importance of timely delivery (within 30-60 minutes) for future collections [34].

Q4: Why is standardizing the abstinence period so critical for research on sperm epigenetics?

- Rationale: The epigenetic landscape of sperm, including histone retention and DNA methylation, can be dynamic. Varying abstinence periods may introduce uncontrolled variability in these epigenetic marks, confounding research results. Standardization ensures that observed epigenetic differences are due to experimental conditions and not pre-analytical variables [34] [37].

Q5: Our laboratory is setting up a new sperm biobank for a large cohort study. What are the key considerations for ensuring sample quality and epigenetic integrity?

- Standardization: Implement and document identical SOPs for collection, processing, and freezing across all samples. This includes strict adherence to abstinence guidelines, consistent use of reagents and cryoprotectants, and uniform freezing protocols [35].

- Training & Competency: Ensure all staff are trained and competency-assessed according to guidelines (e.g., ASRM), performing a sufficient number of procedures annually to maintain proficiency [35].

- Storage & Monitoring: Use a robust inventory system with 24/7 temperature monitoring for liquid nitrogen storage tanks to ensure sample security and traceability [35].

The standardization of sperm epigenetic protocols across laboratories represents a critical step forward in male fertility research and assisted reproductive technology (ART). DNA methylation, a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, plays a crucial role in gene regulation, genomic imprinting, and embryonic development. For researchers and drug development professionals working in reproductive medicine, selecting the appropriate methylation profiling method is paramount for obtaining accurate, reproducible, and biologically relevant data. This technical support center provides a comprehensive comparison of three principal DNA methylation analysis techniques—Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS), and Methylation Microarrays—with a specific focus on their application in sperm epigenetics research. The following sections offer detailed troubleshooting guides, methodological protocols, and comparative frameworks to support experimental standardization across different laboratory settings.

Technical Comparison of Major DNA Methylation Assays

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) is considered the gold standard for DNA methylation analysis, providing single-base resolution methylation measurements across the entire genome. The method relies on sodium bisulfite conversion, which transforms unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged, followed by next-generation sequencing [38]. This technique covers approximately 80% of all CpG sites in the human genome, enabling comprehensive methylation profiling [39].

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) offers a cost-effective alternative that combines restriction enzyme digestion with bisulfite sequencing. This method uses methylation-insensitive restriction enzymes (typically MspI) to digest genomic DNA, enriching for CpG-rich regions including promoters, CpG islands, and other regulatory elements. Following digestion, fragments are size-selected, bisulfite-treated, and sequenced [38]. While RRBS covers only about 5-10% of CpGs genome-wide, it focuses on functionally relevant regions with high CpG density [38].

Methylation Microarrays, particularly Illumina's Infinium platforms (such as the EPIC array), utilize bisulfite-converted DNA hybridized to oligonucleotide probes fixed on beads. The current EPIC array covers over 935,000 CpG sites, extensively profiling promoter regions, gene bodies, enhancers, and other regulatory elements [39] [40]. This technology provides a balanced approach between coverage, cost, and throughput, making it suitable for large-scale epigenetic studies.

Comparative Performance Table

Table 1: Technical comparison of WGBS, RRBS, and Methylation Microarrays for DNA methylation analysis

| Parameter | WGBS | RRBS | Methylation Microarrays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Single-base | Single-base | Single-CpG (predefined sites) |

| Genomic Coverage | ~80% of CpGs (virtually entire genome) | ~5-10% of CpGs (CpG-rich regions) | >935,000 predefined CpG sites (EPIC array) |

| Coverage Bias | Minimal bias | Biased toward CpG islands and promoters | Designed coverage of regulatory regions |

| DNA Input Requirements | High (≥1μg) | Moderate (100-500ng) | Low (100-500ng) |

| DNA Degradation Concerns | High (bisulfite causes fragmentation) | High (bisulfite causes fragmentation) | Tolerant of partially degraded DNA, compatible with FFPE samples |

| Cost per Sample | High | Moderate | Low to moderate |

| Throughput | Low to moderate | Moderate | High |

| Data Analysis Complexity | High (requires advanced bioinformatics) | Moderate to high | Moderate (established pipelines) |

| Best Applications | Discovery-phase studies, novel biomarker identification, comprehensive methylation profiling | Cost-effective targeted methylation analysis, large cohort studies focusing on regulatory regions | Large-scale epidemiological studies, clinical biomarker validation, multi-center studies |

Emerging Alternative Technologies

Recent methodological advances have introduced new approaches that address limitations of traditional bisulfite-based methods. Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) utilizes enzymatic conversion rather than chemical bisulfite treatment, offering improved DNA preservation and reduced sequencing bias while maintaining single-base resolution [41] [38]. Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) enables direct detection of methylation without conversion through long-read sequencing, providing access to challenging genomic regions and haplotype-resolution methylation profiling [41] [38]. These emerging technologies show particular promise for sperm epigenetics, where DNA integrity and comprehensive region coverage are paramount concerns.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Method Selection Guidance

Q: Which DNA methylation method is most suitable for establishing standardized sperm epigenetic protocols across multiple laboratories?

A: The choice depends on your specific research objectives, budget, and technical capabilities:

- For discovery-phase studies aiming to identify novel sperm-specific methylation biomarkers, WGBS provides the most comprehensive coverage [41] [39].

- For large-scale multi-center studies with hundreds to thousands of samples, methylation microarrays offer the best combination of throughput, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness [40].

- For focused analysis of promoter regions and CpG islands with limited budget, RRBS represents a balanced option [38].

- For labs concerned about DNA degradation during bisulfite treatment, EM-seq provides a robust alternative with better DNA preservation [41] [38].

Consider starting with a pilot study comparing methods on a subset of samples to determine which approach best addresses your specific research questions before scaling up to full multi-center standardization.

Q: What method is most appropriate for analyzing limited sperm samples with low DNA concentration?

A: For limited sperm samples:

- Methylation microarrays typically require only 100-500ng of DNA and demonstrate good performance with suboptimal samples [40].

- RRBS can work with 100-500ng input, though lower inputs may affect coverage [38].

- WGBS generally requires ≥1μg of high-quality DNA, making it less suitable for limited samples [39].

- EM-seq shows improved performance with low-input samples compared to WGBS, potentially offering a good compromise between data quality and input requirements [38].

Technical Issue Resolution

Q: How can we address incomplete bisulfite conversion in our sperm DNA samples?

A: Incomplete bisulfite conversion leads to false positive methylation calls. To troubleshoot:

- Verify conversion efficiency by including synthetic unmethylated controls or assessing methylation levels at known unmethylated regions.

- Optimize conversion conditions by ensuring complete DNA denaturation before bisulfite treatment and preventing renaturation during conversion.

- Consider alternative methods such as EM-seq, which uses enzymatic conversion and may provide more consistent results, particularly for GC-rich regions like CpG islands [39] [38].

- Use fresh bisulfite reagents and strictly control reaction temperature and duration according to manufacturer recommendations.

Q: Our sperm samples show significant DNA fragmentation. How does this impact method selection?

A: DNA fragmentation presents particular challenges:

- WGBS and RRBS are highly sensitive to DNA fragmentation since bisulfite treatment further degrades DNA [39] [38].

- Methylation microarrays are more tolerant of partially degraded DNA and are compatible with FFPE samples, making them more robust for compromised sperm samples [40] [38].

- EM-seq causes less DNA damage than bisulfite treatment, offering advantages for fragmented samples [41] [38].

- Library preparation protocols specifically designed for degraded DNA may improve results regardless of the selected method.

Data Quality and Analysis

Q: What quality control metrics should we implement for cross-laboratory standardization?

A: Implement a comprehensive QC framework including:

- Bisulfite conversion efficiency (>99% recommended) for conversion-based methods [31].