Unraveling the Idiopathic Puzzle: Key Challenges and Emerging Solutions in POI Genetic Diagnosis

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) presents a significant diagnostic challenge, with a substantial proportion of cases historically classified as idiopathic.

Unraveling the Idiopathic Puzzle: Key Challenges and Emerging Solutions in POI Genetic Diagnosis

Abstract

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) presents a significant diagnostic challenge, with a substantial proportion of cases historically classified as idiopathic. This article synthesizes current research to address the complexities of genetic diagnosis in idiopathic POI. It explores the evolving etiological landscape, where improved diagnostics have reduced idiopathic cases but revealed a multifaceted genetic architecture involving chromosomal abnormalities, single-gene mutations, and oligogenic contributions. We evaluate advanced methodologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS) and array-CGH that now identify genetic anomalies in over 50% of previously idiopathic cases. The content further addresses critical interpretation pitfalls, such as variants of uncertain significance (VUS), and discusses validation strategies and comparative genomic approaches. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review outlines a path toward refined diagnostic frameworks and personalized therapeutic interventions by dissecting these core challenges.

The Shifting Etiological Landscape and Genetic Complexity of Idiopathic POI

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) represents a significant challenge in reproductive medicine, characterized by the loss of ovarian function before age 40. For decades, the majority of POI cases were classified as idiopathic due to diagnostic limitations, creating a substantial knowledge gap for researchers and clinicians. Recent epidemiological shifts reveal a dramatic transformation in this etiological distribution. Where once idiopathic cases dominated, advanced diagnostics and changing medical practices have substantially increased the proportion of identifiable causes. This paradigm shift from unknown to known etiologies fundamentally alters research approaches, enabling more targeted investigations into genetic architecture, pathogenic mechanisms, and potential therapeutic interventions. Understanding this transition is crucial for developing effective diagnostic strategies and addressing the remaining challenges in idiopathic POI.

Contemporary studies demonstrate a remarkable reduction in idiopathic cases. A 2025 comparative analysis revealed that idiopathic POI decreased from 72.1% in a historical cohort (1978-2003) to 36.9% in a contemporary cohort (2017-2024), while iatrogenic causes increased more than fourfold from 7.6% to 34.2% [1]. This redistribution reflects both improved diagnostic capabilities and the success of oncological treatments that unfortunately result in gonadal damage. The current prevalence of POI etiologies now stands at genetic (9.9%), autoimmune (18.9%), iatrogenic (34.2%), and idiopathic (36.9%) [1]. These findings underscore the critical need to reevaluate research priorities and methodological approaches to address the remaining idiopathic cases and their diagnostic challenges.

Table 1: Changing Prevalence of POI Etiologies Over Time

| Etiology | Historical Cohort (1978-2003) | Contemporary Cohort (2017-2024) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic | 72.1% | 36.9% | -35.2% |

| Iatrogenic | 7.6% | 34.2% | +26.6% |

| Autoimmune | 8.7% | 18.9% | +10.2% |

| Genetic | 11.6% | 9.9% | -1.7% |

Current Etiological Distribution of POI

Established Etiological Categories

The contemporary classification of POI encompasses several well-defined etiological categories, each with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and clinical implications. Iatrogenic POI has emerged as the leading identifiable cause, accounting for approximately one-third of all cases. This category primarily results from gonadotoxic cancer treatments, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with alkylating agents like cyclophosphamide and platinum-based drugs like cisplatin representing the most damaging to ovarian reserve [1] [2]. The rising prevalence reflects improved long-term survival for cancer patients, particularly childhood cancer survivors among whom POI prevalence reaches 18.6% [1]. Surgical interventions involving ovarian resection also contribute to this category, with laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy identified as a significant risk factor [2].

Autoimmune etiologies constitute the second largest identifiable category, implicated in approximately 18.9% of contemporary POI cases [1]. The pathogenesis involves lymphocytic infiltration targeting steroidogenic cells, leading to progressive follicular depletion. Multiple autoimmune conditions associate with POI, including Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Addison's disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis [1] [2]. The detection of steroidogenic cell autoantibodies, particularly against 21-hydroxylase, supports an autoimmune mechanism. Hashimoto's thyroiditis demonstrates a particularly strong association, conferring an 89% higher risk of amenorrhea and a 2.4-fold increased risk of infertility due to ovarian failure [1].

Genetic causes represent a more complex and evolving etiological category. While accounting for 9.9% of contemporary cases [1], the understanding of genetic contributions has undergone significant revision. Chromosomal abnormalities, particularly X-chromosome anomalies like Turner syndrome (45,X and mosaic variants) and fragile X premutations (FMR1 gene with 55-200 CGG repeats), remain the most established genetic causes [1]. Turner syndrome affects approximately 1 in 2000-2500 live-born females, with over 80% experiencing absent spontaneous menstruation or developing POI [2]. Beyond chromosomal abnormalities, mutations in numerous autosomal genes involved in meiosis, DNA repair, and folliculogenesis have been implicated, though their penetrance and pathogenicity require careful interpretation [3].

Table 2: Current Prevalence and Characteristics of Major POI Etiologies

| Etiology | Prevalence | Key Examples | Primary Pathogenic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iatrogenic | 34.2% | Chemotherapy, Radiotherapy, Ovarian Surgery | Direct follicular damage, DNA damage in oocytes, oxidative stress, vascular and stromal damage |

| Autoimmune | 18.9% | Autoimmune oophoritis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Addison's disease | Lymphocytic infiltration of steroidogenic cells, antibody-mediated destruction of follicular components |

| Genetic | 9.9% | Turner syndrome, FMR1 premutation, autosomal gene mutations | Chromosomal abnormalities, single gene mutations affecting folliculogenesis, meiosis, or DNA repair |

| Idiopathic | 36.9% | Unknown | Presumed genetic or environmental factors not yet identified |

Environmental and Other Factors

Beyond the major categories, environmental factors represent an increasingly recognized contributor to POI pathogenesis. Environmental toxicants (ETs) encompass atmospheric particulate matter, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), pesticides, microplastics, heavy metals, and cigarette smoke [2]. These compounds can promote ovarian damage through multiple pathways, including oxidative stress, DNA damage, epigenetic modifications, and accelerated follicular atresia. Epidemiological studies have identified smoking as a significant risk factor, with up to a 2.75-fold elevated risk of POI among smokers [1]. The global increase in environmental pollution underscores the potential growing impact of these factors on ovarian function.

Additional etiological factors include infectious agents and metabolic disorders. While rare, viral infections including mumps, HIV, and recently SARS-CoV-2 have been associated with POI onset [1] [2]. The mechanisms may involve direct viral damage to ovarian tissue or inflammatory-mediated follicular destruction. Classic galactosemia, a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder caused by deficiency of galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT), represents another established cause, though not all affected individuals develop POI [1]. The toxic accumulation of galactose metabolites in the ovaries is thought to underlie the pathogenic process, though the precise mechanism remains incompletely understood.

The Shifting Diagnostic Paradigm: Implications for Research

Advancements in Diagnostic Capabilities

The substantial reduction in idiopathic POI cases reflects significant advancements in diagnostic methodologies and their integration into clinical practice. Genetic testing has evolved from chromosomal analysis to include targeted genetic panels and whole exome sequencing (WES), expanding the repertoire of identifiable genetic causes. Recent studies have identified more than 75 genes associated with POI, primarily involved in meiosis and DNA repair mechanisms [1]. The 2024 evidence-based guideline from ESHRE/ASRM provides updated recommendations for genetic evaluation, including FMR1 premutation testing for all women with POI and consideration of chromosome microarray analysis [4].

Immunological assessment has similarly advanced, with improved antibody detection methodologies enhancing the identification of autoimmune etiologies. The detection of steroidogenic cell autoantibodies, particularly against 21-hydroxylase, supports an autoimmune mechanism for POI [1]. Additionally, the association between thyroid autoantibodies (TgAb, TPOAb) and increased POI risk, even in women with normal thyroid function, has expanded the diagnostic considerations [1]. These diagnostic refinements have been complemented by enhanced hormonal profiling, including the strategic use of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) testing and refined FSH measurement protocols that now require only one elevated FSH level >25 IU/L for diagnosis according to recent guidelines [4].

The integration of multi-omics approaches represents the next frontier in POI diagnostics. Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic analyses offer unprecedented insights into the complex pathogenic networks underlying POI. Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA expression, have emerged as significant contributors to POI pathogenesis [2]. Studies have demonstrated distinct epigenetic features in ovarian granular cells from women with diminished ovarian reserve, including increased DNA methylation variability [2]. These advanced molecular profiling techniques continue to unravel the complexity of POI and further reduce the idiopathic category.

Persistent Challenges in Genetic Diagnosis

Despite these advancements, significant challenges persist in genetic diagnosis, particularly regarding variant interpretation and penetrance. Groundbreaking research published in Nature Medicine has fundamentally challenged conventional thinking about genetic causes of POI [3] [5]. In the largest study to date, analyzing genetic data from 104,733 women in UK Biobank, researchers found that 98% of women carrying variations previously considered pathogenic for POI in fact experienced menopause over age 40, ruling out POI diagnosis [3] [5]. This suggests that many variants previously reported as causative may have low penetrance or represent benign population polymorphisms.

The oligogenic model of POI inheritance has gained support, proposing that the condition may result from combinations of variants in multiple genes rather than single-gene defects [3] [6]. This complex genetic architecture complicates diagnostic interpretation and genetic counseling. The traditional monogenic framework fails to capture this complexity, potentially leading to misinterpretation of genetic testing results. As Professor Anna Murray of the University of Exeter notes, "It now seems likely that premature menopause is caused by a combination of variants in many genes, as well as non-genetic factors" [3]. This paradigm shift necessitates more nuanced approaches to genetic analysis in POI research.

Functional validation remains a critical step in establishing pathogenicity, yet implementation challenges persist. The 2023 UK Biobank study identified genetic drivers with more subtle effects on reproductive longevity, including variations in TWNK and SOHLH2 genes associated with menopause up to three years earlier than the general population [3] [5]. However, confirming the functional consequences of these and other variants requires sophisticated experimental models and substantial resources. These limitations contribute to the continued classification of cases as idiopathic despite identified genetic variants, highlighting the gap between variant detection and pathogenicity determination.

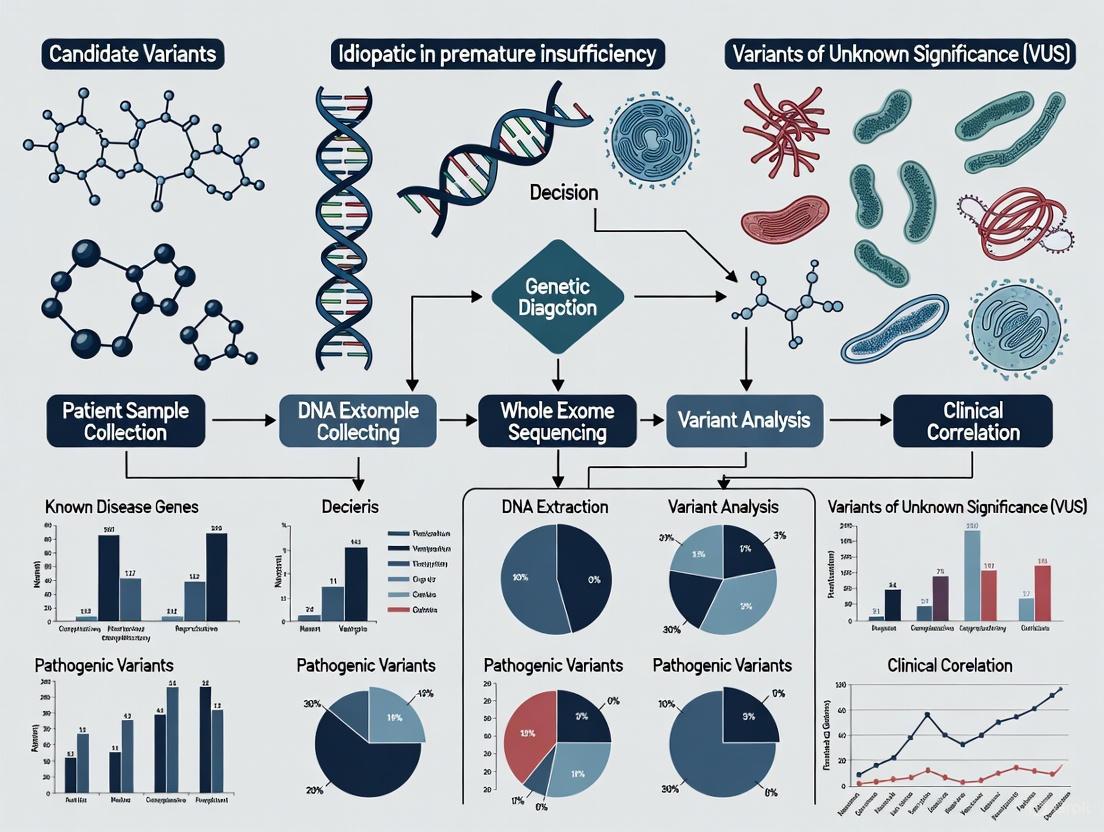

Diagram 1: Contemporary POI Etiological Classification Framework. This diagram illustrates the current classification system for POI etiologies, highlighting the multifactorial nature of the condition and the relationship between identifiable and idiopathic causes.

Technical Support: Methodologies for Etiological Investigation

Experimental Protocols for Genetic Analysis

Protocol 1: Whole Exome Sequencing and Variant Filtering for POI Research

Purpose: To identify potential pathogenic genetic variants in patients with idiopathic POI.

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from peripheral blood using standardized extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit).

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries using exome capture kits (e.g., Illumina Nextera Flex for Enrichment) targeting >99% of coding regions.

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on appropriate platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq 6000) with minimum 100x coverage.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align sequences to reference genome (GRCh38) using BWA-MEM or similar aligner

- Perform variant calling with GATK Best Practices workflow

- Annotate variants using ANNOVAR with population databases (gnomAD, 1000 Genomes), prediction tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2), and disease databases (ClinVar, HGMD)

- Variant Filtering:

- Remove variants with allele frequency >0.1% in population databases

- Retain protein-altering variants (missense, nonsense, splice-site, indels)

- Prioritize genes with known POI associations and genes in related biological pathways

- Validation: Confirm prioritized variants by Sanger sequencing

- Segregation Analysis: Test available family members to assess co-segregation with phenotype

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For variants of uncertain significance, perform in silico structural modeling and consult gene constraint metrics (pLI scores)

- Consider oligogenic inheritance by analyzing potential compound heterozygosity or combinations of variants in interacting genes

- Be aware of technical limitations in detecting repeat expansions or complex structural variations

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of POI-Associated Genetic Variants

Purpose: To establish pathogenicity of identified genetic variants through experimental assessment.

Methodology:

- Plasmid Construction: Generate expression vectors containing wild-type and mutant cDNA sequences of the gene of interest.

- Cell Culture: Utilize appropriate cell lines (e.g., HEK293T, COV434, or patient-derived fibroblasts) maintained under standard conditions.

- Transfection: Introduce expression vectors using lipid-based transfection reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000).

- Functional Assays (selection based on gene function):

- Protein Expression: Assess by Western blot and immunofluorescence

- Localization: Determine subcellular localization using confocal microscopy with organelle-specific markers

- Protein-Protein Interactions: Evaluate by co-immunoprecipitation or yeast two-hybrid systems

- Enzymatic Activity: Measure using appropriate substrate conversion assays

- Gene Expression Analysis: Quantify mRNA levels by RT-qPCR and assess alternative splicing by RT-PCR

- CRISPR/Cas9 Modeling: Generate isogenic cell lines with introduced variants using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing for phenotypic comparison

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Include multiple biological replicates and appropriate positive/negative controls

- For missense variants, compare to known pathogenic and benign variants in the same protein

- Consider protein stability and degradation pathways when interpreting expression results

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for POI Etiological Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Analysis Tools | Whole exome sequencing kits, Sanger sequencing reagents, CRISPR/Cas9 components | Identification and validation of genetic variants | Prioritize kits with high coverage uniformity; validate CRISPR edits thoroughly |

| Immunoassay Reagents | ELISA kits for anti-ovarian antibodies, 21-hydroxylase antibodies, inflammatory cytokines | Detection of autoimmune markers | Use standardized controls; confirm specificity with blocking experiments |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary granulosa cells, ovarian cortical tissue, established cell lines (COV434, KGN) | In vitro modeling of ovarian function | Optimize culture conditions for primary cells; authenticate cell lines regularly |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | RNA extraction kits, cDNA synthesis kits, qPCR primers/probes, Western blot reagents | Gene expression and protein analysis | Include multiple reference genes for qPCR; validate antibodies for specific applications |

| Animal Models | Transgenic mice, xenograft models, chemotherapeutic injury models | In vivo pathophysiological studies | Consider species differences in ovarian physiology; monitor estrous cycles |

| Histopathology Tools | Tissue fixation/embedding supplies, immunohistochemistry reagents, multiplex fluorescence kits | Ovarian tissue analysis | Optimize antigen retrieval; use appropriate positive controls for staining |

FAQs: Addressing Key Challenges in POI Etiology Research

Q1: What proportion of POI cases remain truly idiopathic with current diagnostic capabilities?

Recent comprehensive studies indicate that approximately 36.9% of POI cases remain classified as idiopathic after thorough evaluation [1]. This represents a substantial decrease from historical rates of 72.1%, reflecting significant advances in diagnostic methodologies. However, the term "idiopathic" continues to evolve as new genetic, autoimmune, and environmental factors are identified. Research suggests that many idiopathic cases likely represent complex genetic etiologies with oligogenic inheritance patterns or gene-environment interactions that current technologies cannot fully characterize [3] [6].

Q2: How has our understanding of genetic contributions to POI changed recently?

Groundbreaking research from 2023 has fundamentally altered our understanding of genetic contributions to POI. The largest study to date, analyzing data from over 100,000 women, found that 98% of women carrying genetic variants previously considered pathogenic for POI actually experienced menopause after age 40 [3] [5]. This indicates that many reported "causative" variants have low penetrance and that POI likely results from combinations of variants in multiple genes rather than single-gene defects. This shift toward an oligogenic model complicates genetic diagnosis but more accurately reflects the complex inheritance of most POI cases.

Q3: What are the most significant methodological challenges in POI etiological research?

Key methodological challenges include: (1) Variant interpretation difficulties - distinguishing truly pathogenic variants from low-penetrance alleles or benign polymorphisms; (2) Oligogenic complexity - identifying and validating combinations of variants that collectively contribute to disease risk; (3) Functional validation bottlenecks - the time and resource-intensive nature of experimentally confirming variant pathogenicity; (4) Model system limitations - the lack of ideal in vitro systems that fully recapitulate human ovarian physiology; and (5) Ethical constraints - limitations on experimental manipulation of human ovarian tissue [3] [2] [6].

Q4: Which environmental factors have the strongest evidence for contributing to POI?

Epidemiological and experimental studies have identified several environmental factors with substantial evidence for POI contribution: (1) Cigarette smoking - associated with up to 2.75-fold increased risk in a dose-dependent manner [1]; (2) Endocrine-disrupting chemicals - including phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA and analogs), and pesticides that promote oxidative stress and follicular atresia [1] [2]; (3) Chemotherapeutic agents - particularly alkylating compounds like cyclophosphamide and platinum-based drugs like cisplatin [1]; and (4) Atmospheric particulate matter - associated with increased DNA damage and oxidative stress in ovarian tissue [2].

Q5: What diagnostic approach is recommended for maximizing etiological identification?

The 2024 evidence-based guideline from ESHRE/ASRM recommends: (1) Comprehensive history - including family history, exposures, and autoimmune symptoms; (2) Genetic testing - FMR1 premutation screening for all patients and chromosomal analysis for those with primary amenorrhea; (3) Autoimmune evaluation - assessment for associated conditions and relevant autoantibodies; (4) Hormonal profiling - including FSH (>25 IU/L on one measurement now sufficient for diagnosis) and AMH where uncertainty exists [4]. A systematic, stepwise approach incorporating these elements maximizes etiological identification while remaining cost-effective.

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Diagnostic Workflow for POI Etiology. This diagram outlines a systematic approach to etiological investigation in POI, illustrating the sequential evaluation process and the point at which idiopathic classification is appropriate after comprehensive assessment.

The landscape of POI etiology has transformed dramatically, with identifiable causes now representing the majority of cases. This shift from idiopathic to identifiable reflects substantial progress in diagnostic capabilities and etiological understanding. However, significant challenges remain, particularly in deciphering the complex genetic architecture underlying remaining idiopathic cases. The recognition that POI likely results from oligogenic combinations rather than single-gene defects necessitates more sophisticated analytical approaches that consider variant combinations, gene-gene interactions, and gene-environment interplay.

Future research directions should prioritize several key areas: (1) Multi-omics integration - combining genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data to construct comprehensive pathogenic networks; (2) Advanced functional models - developing more physiologically relevant in vitro systems, including organoid cultures and microfluidic platforms that better recapitulate ovarian microenvironments; (3) Environmental exposure mapping - systematically characterizing the exposome and its interactions with genetic susceptibility; and (4) Computational approaches - implementing artificial intelligence and machine learning to identify complex patterns across diverse data types. These approaches promise to further reduce the idiopathic category and enable truly personalized management strategies for women with POI.

The progressive elucidation of POI pathogenesis underscores the dynamic nature of etiological classification in complex disorders. As research methodologies continue to advance, the remaining idiopathic cases will inevitably yield their secrets, paving the way for improved diagnostics, targeted interventions, and ultimately better outcomes for affected women. The journey from idiopathic to identifiable represents both a remarkable achievement and an ongoing challenge for the research community.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the current understanding of the genetic contribution to idiopathic Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI)?

POI is a highly heterogeneous condition, and its genetic architecture is complex. While approximately 70% of POI cases were historically classified as idiopathic, advanced genetic techniques are now revealing underlying causes in a significant portion of these patients [7] [8]. Genetic factors are pivotal, contributing to approximately 20–25% of all POI cases with known causes [8]. A large-scale whole-exome sequencing study of 1,030 POI patients identified pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in known POI-causative genes in 18.7% of cases. When novel candidate genes from association analyses were included, the genetic contribution rose to 23.5% of cases [9]. The genetic yield is even higher in specific subgroups; for instance, one study combining array-CGH and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) identified a genetic anomaly in 57.1% (16/28) of idiopathic POI patients [7].

Table 1: Genetic Diagnostic Yield in Recent POI Studies

| Study Description | Cohort Size | Overall Genetic Diagnostic Yield | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-scale WES study [9] | 1,030 patients | 23.5% (242/1030) | Included known and novel candidate genes |

| Combined array-CGH & NGS panel [7] | 28 idiopathic patients | 57.1% (16/28) | 39.3% of patients had a family history of POI |

| Genetic contribution in POI [8] | N/A | 20-25% | Figure for all POI cases with a known cause |

FAQ 2: How do chromosomal abnormalities contribute to POI?

Chromosomal abnormalities are a well-established cause of POI, accounting for approximately 10-13% of cases [8] [1]. These abnormalities are more frequently observed in women with primary amenorrhea (21.4%) compared to those with secondary amenorrhea (10.6%) [1]. The most significant contributors are abnormalities of the X chromosome, as normal ovarian function requires two active copies of X-linked genes.

- X Chromosome Aneuploidies: Turner Syndrome (45, X) is a major cause, resulting from the complete or partial absence of an X chromosome and leading to accelerated follicular atresia [8] [1]. Trisomy X Syndrome (47, XXX) has also been associated with diminished ovarian reserve and an increased risk of POI [8].

- Structural Chromosomal Abnormalities: These include isochromosomes, deletions, and translocations, particularly within defined "critical regions" on the long arm (q) of the X chromosome (Xq13.1–q21.33 and Xq24–q27). X-autosomal translocations can also disrupt ovarian function through gene disruption, meiosis errors, or positional effects [8].

FAQ 3: What is the role of monogenic (single-gene) defects in POI?

Monogenic inheritance refers to traits or conditions caused by pathogenic variants in a single gene [10]. In POI, over 75 genes have been implicated, impacting processes critical for ovarian function [1]. These monogenic causes can present as either non-syndromic (isolated POI) or syndromic (POI as part of a broader clinical picture).

- Non-Syndromic POI: Genes involved include those critical for ovarian development, folliculogenesis, meiosis, and DNA repair. Examples include NOBOX, BMP15, GDF9, and FSHR [1] [9].

- Syndromic POI: Several genetic syndromes feature POI as a component. Examples include:

- Fragile X-associated POI (FXPOI): Caused by a premutation (55-200 CGG repeats) in the FMR1 gene [1].

- Galactosemia: An autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the GALT gene, leading to toxic metabolite accumulation and POI in 80-90% of female patients [8] [1].

- Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type 1 (APS-1): Caused by mutations in the AIRE gene [8].

- Ataxia-telangiectasia (AT): Caused by mutations in the ATM gene, which plays a crucial role in DNA damage repair [8].

Table 2: Examples of Key Monogenic Causes of POI

| Gene | Primary Functional Category | Phenotype | Prevalence / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMR1 (premutation) | Gene regulation | FXPOI | Highest risk with 70-100 CGG repeats [1] |

| GALT | Metabolism | Galactosemia with POI | 80-90% of patients affected [1] |

| AIRE | Autoimmune regulation | APS-1 with POI | ~41% of APS-1 patients have POI [8] |

| NR5A1 | Gonadal development | Isolated or syndromic POI | One of the most frequently mutated genes in a large cohort (1.1%) [9] |

| EIF2B2 | Mitochondrial function | Isolated POI | Had the highest prevalence of pathogenic alleles in one study (0.8%) [9] |

FAQ 4: Is there evidence for oligogenic inheritance in POI?

Yes, emerging evidence strongly suggests that oligogenic inheritance—where a few genes interact to cause a disease—plays a significant role in POI [11] [12]. This complexity challenges the traditional monogenic view.

Research indicates that the cumulative effects of genetic defects influence the clinical severity of POI. A large WES study found that patients with primary amenorrhea had a substantially higher frequency of biallelic and multi-heterozygous (variants in different genes) pathogenic variants compared to those with secondary amenorrhea [9]. This suggests that the combined impact of variants in multiple genes can lead to a more severe phenotype. The post-genome era, with increased access to NGS, is allowing researchers to unravel these complex genetic mechanisms behind POI and other inherited disorders [11].

FAQ 5: What are the key experimental protocols for genetic analysis in POI research?

A comprehensive genetic workup for POI involves a combination of techniques to capture different types of variants.

- Karyotyping and Chromosomal Microarray (array-CGH): These are first-line tests to identify numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities, including large deletions/duplications (copy number variations, or CNVs). Array-CGH can detect CNVs of a minimum of 60 kb [7].

- FMR1 CGG Repeat Analysis: This specific test is crucial for diagnosing FXPOI and should be performed, especially in patients with a family history of POI or intellectual disability [1].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): This is the cornerstone for identifying single nucleotide variations (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels).

- Gene Panel Sequencing: Uses a custom capture design targeting known and suspected POI genes (e.g., 163 genes) [7].

- Whole Exome Sequencing (WES): Sequences all protein-coding genes and is effective for identifying novel candidate genes in research settings [9].

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): Captures the entire genome, including non-coding regions, offering the most comprehensive analysis.

Table 3: Key Methodologies for Genetic Diagnosis in POI

| Technique | Primary Use | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|

| Karyotype | Detect numerical and large structural chromosomal abnormalities. | Essential for diagnosing Turner Syndrome and other aneuploidies. |

| Array-CGH | Genome-wide detection of CNVs. | Identifies microdeletions/duplications below the resolution of karyotyping. |

| FMR1 Testing | Detect CGG triplet repeat premutation. | A specific test for a common genetic cause; not detected by NGS. |

| NGS (Panel/WES) | Identify SNVs/indels in single genes. | The most effective method for detecting monogenic causes. A combined approach with array-CGH increases diagnostic yield [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Combined Array-CGH and Targeted NGS Panel Analysis [7]

- Sample Collection: Obtain peripheral blood samples from patients after informed consent. DNA is extracted using standardized kits (e.g., QIAsymphony DNA midi kits).

- Array-CGH:

- Platform: SurePrint G3 Human CGH Microarray 4 × 180 K.

- Procedure: Follow supplier's recommendations for hybridization.

- Bioinformatics Analysis: Use software like CytoGenomics v5.0 and Cartagenia Bench Lab CNV v5.1 to identify CNVs. Report CNVs with a minimum size of 60 kb.

- Targeted NGS:

- Capture Design: Use a custom SureSelect capture design targeting a panel of genes (e.g., 163 genes involved in ovarian function).

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Use SureSelect XT-HS reagents on a system like Magnis, followed by sequencing on a platform like Illumina NextSeq 550.

- Bioinformatics Analysis: Perform using a pipeline such as Alissa Align&Call v1.1 and Alissa Interpret v5.3 for variant calling and annotation.

- Variant Interpretation:

- Filter against population databases (e.g., gnomAD) and variation databases (e.g., ClinVar, HGMD).

- Classify variants according to ACMG guidelines (Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic, Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS), Likely Benign, Benign).

- Correlate genotypes with clinical phenotypes using databases like OMIM and the literature.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the diagnostic genetic analysis for POI:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Genetic Studies in POI

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Product / Software |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from patient samples (e.g., blood). | QIAsymphony DNA midi kits (Qiagen) [7] |

| Array-CGH Platform | For genome-wide detection of copy number variations (CNVs). | SurePrint G3 Human CGH Microarray 4 × 180 K (Agilent) [7] |

| Array-CGH Analysis Software | To identify, visualize, and interpret CNVs from array data. | CytoGenomics v5.0, Cartagenia Bench Lab CNV v5.1 (Agilent) [7] |

| NGS Target Enrichment | To capture and sequence a specific panel of POI-related genes. | SureSelect XT-HS Custom Capture (Agilent) [7] |

| NGS Platform | To perform high-throughput sequencing of captured libraries. | Illumina NextSeq 550 [7] |

| NGS Analysis Pipeline | For alignment, variant calling, annotation, and interpretation. | Alissa Align&Call v1.1 & Alissa Interpret v5.3 [7] |

| Variant Annotation Databases | To filter variants and assess population frequency and pathogenicity. | gnomAD, ClinVar, HGMD [7] [9] |

| Tovopyrifolin C | Tovopyrifolin C | High-Purity Research Compound | Tovopyrifolin C for research. Investigate its bioactivity & mechanism. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Patamostat | Patamostat | Potent Serine Protease Inhibitor | RUO | Patamostat is a potent serine protease inhibitor for research on thrombosis, inflammation, and pancreatitis. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

The following diagram summarizes the complex genetic architecture underlying POI:

FAQs: Navigating Autosomal Gene Analysis in Idiopathic POI

FAQ 1: A significant proportion of POI cases are classified as idiopathic. What is the emerging genetic understanding of these cases?

While historically over 70-90% of POI cases were considered idiopathic, recent advances in genetic testing have significantly reduced this percentage. It is now understood that a substantial genetic component underpins many of these cases, with current estimates of idiopathic forms standing between 39% and 67% [6] [13]. This shift is largely due to the identification of numerous autosomal genes associated with POI. The genetic architecture is highly heterogeneous, involving mutations in over 100 genes, and is not limited to X-chromosome defects [14] [8]. Furthermore, the inheritance patterns in idiopathic POI are now recognized to extend beyond simple monogenic inheritance to include digenic, oligogenic, and polygenic models, where variants in multiple genes collectively contribute to the phenotype [14].

FAQ 2: Which key biological processes, governed by autosomal genes, are most frequently disrupted in POI pathogenesis?

Autosomal genes implicated in POI are integral to a wide range of critical ovarian functions. The primary biological processes and some of the key genes involved are summarized in the table below [8] [14] [6]:

Table 1: Key Biological Processes and Associated Autosomal Genes in POI

| Biological Process | Description of Role in Ovarian Function | Key Associated Autosomal Genes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Repair & Meiosis | Maintains genomic stability during homologous recombination and meiotic division in germ cells. | MCM8, MCM9, MSH4, MSH5, SYCE1, STAG3, FANCE [14] [15] [16] |

| Folliculogenesis | Regulates the development, growth, and maturation of follicles from primordial to antral stages. | BMP15, GDF9, NOBOX, FIGLA, FSHR [14] [13] [16] |

| Ovary Formation & Oogenesis | Controls gonadal differentiation, formation of the ovary, and early development of oocytes. | FOXL2, SOHLH1, LHX8 [14] [16] |

| Mitochondrial Function | Provides energy for oocyte maturation and follicular development; dysfunction can trigger apoptosis. | MRPS22, LRPPRC [8] |

FAQ 3: Our research is focusing on novel therapeutic targets. Which autosomal genes have recently been identified as promising candidates?

Recent genomic studies employing genome-wide association studies (GWAS) integrated with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis have pinpointed several novel autosomal genes with strong causal evidence for POI. Two genes, in particular, stand out as promising druggable targets:

FANCE(FA Complementation Group E): This gene is part of the Fanconi anemia pathway, crucial for DNA repair through homologous recombination. Mendelian randomization and colocalization analyses have established a causal link betweenFANCEand a reduced risk of POI [15].RAB2A(Member RAS Oncogene Family): This gene is involved in autophagy regulation and intracellular vesicle trafficking. Similar analyses have identifiedRAB2Aas a significant factor conferring reduced POI risk, highlighting it as another potential therapeutic target [15].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key findings from this genomic approach to target identification:

FAQ 4: What are the common experimental challenges when validating novel autosomal gene variants in POI?

A major challenge is establishing a definitive causal relationship between a genetic variant and the POI phenotype. Linkage disequilibrium can lead to false positives, where a detected variant is merely linked to the true causal variant rather than being causative itself [15]. Furthermore, the high heterogeneity and proposed oligogenic nature of POI mean that a single variant may be insufficient to cause the disease, requiring investigation of multiple hits in different genes [6] [14]. To overcome these challenges, it is critical to employ colocalization analysis, a Bayesian method that tests whether two traits share the same causal variant. A high posterior probability for H4 (PP.H4 ≥ 0.8) provides strong evidence that the same variant influences both gene expression and POI risk, strengthening causal inference [15]. Functional validation in model systems remains an essential subsequent step.

Troubleshooting Guides for Key Experiments

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Causal Gene Identification via SMR & HEIDI Tests

Objective: To identify genes whose expression levels have a putative causal effect on POI risk using Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR).

Table 2: Troubleshooting the SMR and HEIDI Analysis Workflow

| Step | Protocol Detail | Common Issue | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Input | Use cis-eQTL data (e.g., from GTEx ovary tissue) and POI GWAS summary statistics. | Population stratification confounding results. | Ensure both datasets are from ancestrally matched cohorts (e.g., both of European descent) [15]. |

| 2. SMR Analysis | Run SMR software (v1.3.1) to test for gene-POI associations. | A significant SMR p-value (PSMR) is observed. | This indicates a genetic association, but it could be due to pleiotropy. Proceed to the HEIDI test [15]. |

| 3. HEIDI Test | Perform the heterogeneity test to rule out pleiotropy. | PHEIDI < 0.05. | Interpretation: The association is likely caused by linkage (pleiotropy), not causality. Action: Exclude the gene from the candidate list [15]. |

| 4. Result | Final candidate gene list. | PSMR < 0.05 AND PHEIDI > 0.05. | Interpretation: Supports a causal relationship between gene expression and POI. Action: Proceed to colocalization analysis for further validation [15]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting the Interpretation of Complex Inheritance Patterns

Objective: To correctly design studies and analyze data for POI cases that do not follow simple Mendelian inheritance.

Problem: A proband with a strong family history of POI undergoes targeted sequencing for a known autosomal gene (e.g.,

NOBOX) but no pathogenic variants are found.- Potential Cause: The POI in the family might be caused by a variant in a different gene, or follow a digenic/oligogenic inheritance pattern requiring mutations in two or more genes [14].

- Solution: Expand genetic testing from a single-gene approach to a larger panel of POI-associated genes or clinical exome sequencing. Analytical methods should be employed that can detect the combined effect of multiple medium-effect variants [6] [14].

Problem: A novel missense variant of uncertain significance (VUS) is identified in an autosomal POI gene (e.g.,

BMP15), but its functional impact is unknown.- Investigation Protocol:

- Computational Prediction: Use in silico tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2) to predict variant deleteriousness.

- Family Segregation Analysis: Test for co-segregation of the variant with the POI phenotype across affected and unaffected family members.

- Functional Assay: For a gene like

BMP15, which regulates granulosa cell proliferation and oocyte maturation, an in vitro assay could involve creating the mutant construct, transfecting it into a granulosa cell line, and measuring its impact on SMAD phosphorylation via Western blot compared to wild-type [16] [8].

- Investigation Protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Investigating Autosomal POI Genes

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in POI Research |

|---|---|

| GWAS Summary Data (e.g., FinnGen R11) | Serves as the foundational dataset for identifying genetic variants associated with POI in large populations. Essential for MR studies [15]. |

| Cis-eQTL Datasets (GTEx V8, eQTLGen) | Provides data on how genetic variants affect gene expression in specific tissues like the ovary. Critical for linking GWAS hits to functional genes [15]. |

| SMR & HEIDI Test Software | A specialized software tool (e.g., SMR v1.3.1) used to perform Mendelian randomization and heterogeneity tests to infer causal genes from GWAS and eQTL data [15]. |

| Coloc R Package | A Bayesian statistical tool used for colocalization analysis to determine if two traits share a single causal genetic variant, thereby validating MR findings [15]. |

| Granulosa Cell Line (e.g., KGN, COV434) | An in vitro model for functional validation experiments, particularly for genes involved in folliculogenesis (e.g., BMP15, GDF9, FSHR) to study signaling pathways and steroidogenesis [16]. |

| 9-Fluorenol | 9H-Fluoren-9-ol | High Purity | Research Grade |

| Paliperidone-d4 | Paliperidone-d4 | Deuteration Grade >98% | RUO |

FAQ: Understanding Familial Risk and Heritability

What is the evidence for a genetic component in POI? Population-based studies provide strong evidence that POI has a significant genetic component. A large, multigenerational genealogical study demonstrated excess familial clustering of POI, with relatives of affected women having a significantly higher risk of the condition compared with matched controls [17]. Furthermore, twin studies indicate that the heritability estimate for age at natural menopause is approximately 0.52, suggesting genetic factors explain at least half of the interindividual variation [18].

How much does family history increase the risk of POI? The risk of POI is substantially higher among relatives of affected individuals, with the risk decreasing as the degree of relatedness becomes more distant [17] [6].

- First-degree relatives (mothers, sisters, daughters) have a 18.52-fold increased risk [17] [6].

- Second-degree relatives (aunts, grandmothers, nieces) have a 4.21-fold increased risk [17].

- Third-degree relatives (first cousins) have a 2.67-fold increased risk [17] [6].

An early menopause in a close family member is associated with a 6- to 8-fold increased risk of early or premature menopause [18].

What proportion of POI cases are considered familial? Studies have found that about 6.3% of identified POI cases have an affected relative when assessed via electronic medical records [17]. Other research indicates that up to 31% of patients with POI report a familial form of the condition, and first-degree relatives have an odds ratio of 4.6 for also having POI [6].

What are the common inherited causes of POI? The most well-defined genetic causes include [1] [18]:

- X-chromosome abnormalities: Turner syndrome (45,X and mosaic variants) is a common cause, particularly of primary amenorrhea.

- FMR1 premutations: A premutation (55-200 CGG repeats) in the FMR1 gene is the most common single-gene cause, accounting for POI in about 6% of women with a normal karyotype. This is known as Fragile X-associated Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (FXPOI) [1] [19].

- Autosomal gene mutations: Mutations in over 75 genes involved in ovarian development, meiosis, and DNA repair have been implicated, though many are rare [20].

Quantitative Data on POI Etiology and Risk

Table 1: Changing Etiological Spectrum of POI Over Time

| Etiology | Historical Cohort (1978-2003) | Contemporary Cohort (2017-2024) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic | 72.1% | 36.9% | Significant decrease (p<0.05) |

| Iatrogenic | 7.6% | 34.2% | >4-fold increase (p<0.05) |

| Autoimmune | 8.7% | 18.9% | >2-fold increase (p<0.05) |

| Genetic | 11.6% | 9.9% | Not statistically significant |

Data adapted from a comparative study of 283 patients from a single tertiary center [1].

Table 2: Familial Risk of POI

| Relationship to Proband | Relative Risk (RR) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| First-Degree Relatives | 18.52 | 10.12 – 31.07 |

| Second-Degree Relatives | 4.21 | 1.15 – 10.79 |

| Third-Degree Relatives | 2.65 | 1.14 – 5.21 |

Data from a population-level genealogical study of 396 cases [17] [6].

Experimental Protocols for Genetic Diagnosis

Protocol 1: First-Tier Genetic Testing for POI This protocol is recommended in clinical practice guidelines for the initial workup of a new POI diagnosis [4] [18].

Karyotype Analysis (High-Resolution)

- Objective: To identify numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities, particularly X-chromosome anomalies like Turner syndrome and translocations.

- Methodology: Standard cytogenetic analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes. A minimum of 20 metaphase cells should be analyzed, with resolution to at least 550 bands.

- Clinical Value: Chromosomal abnormalities have a prevalence of 10-13% in POI and are more common in women with primary amenorrhea (21.4%) than secondary amenorrhea (10.6%) [1] [18].

FMR1 Gene Molecular Analysis

- Objective: To detect CGG trinucleotide repeat expansions in the FMR1 gene, identifying premutation carriers.

- Methodology: PCR and/or Southern blot analysis of DNA extracted from peripheral blood. The number of CGG repeats is quantified.

- Interpretation: Normal: <45 repeats; Intermediate/Gray Zone: 45-54; Premutation: 55-200; Full Mutation: >200. POI risk is highest with 70-100 repeats [1].

- Clinical Value: Offered to all women with POI and a normal karyotype, as 6% will carry a premutation. Crucial for genetic counseling due to the risk of having children with Fragile X syndrome [19].

Protocol 2: Advanced Genomic Investigation for Idiopathic POI This protocol is used in a research setting to identify novel genetic causes in cases where first-tier testing is uninformative.

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (array CGH)

- Objective: To detect submicroscopic chromosomal copy-number variations (CNVs) not visible on karyotype.

- Methodology: Hybridization of patient and reference DNA to a microarray platform containing thousands of genomic probes. Identifies deletions and duplications.

- Research Value: A study found a 2.5-fold enrichment for rare CNVs on the X chromosome comprising ovary-expressed genes in POI patients, supporting a polygenic etiology [18].

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

- Objective: To identify pathogenic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) in POI-associated genes.

- Methodology:

- Targeted Gene Panels: NGS of a predefined set of genes known to be associated with ovarian function and POI.

- Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing (WES/WGS): Unbiased sequencing of all protein-coding genes or the entire genome to discover novel candidate genes.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Pipeline includes alignment to a reference genome, variant calling, annotation, and filtering against population databases. Focus on rare, protein-altering variants.

- Research Value: In a recent study of 1030 POI patients, 23.5% had potentially pathogenic mutations identified via genetic testing, expanding the understanding of the genetic architecture of POI [20].

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Networks in POI

The following diagram illustrates the key biological processes and a subset of implicated genes in the pathogenesis of POI, highlighting its complex and polygenic nature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for POI Genetic Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Primers | Amplification of specific genomic regions for Sanger sequencing or validation. | Targeted sequencing of known POI genes like FMR1 CGG repeats, BMP15, GDF9 [1]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Preparation of fragmented DNA for high-throughput sequencing on platforms like Illumina. | Constructing libraries for whole exome sequencing or targeted gene panels in idiopathic POI cohorts [20]. |

| Array CGH Microarrays | Genome-wide screening for copy-number variations with high resolution. | Identifying novel microdeletions/duplications on the X chromosome and autosomes in POI patients [18]. |

| Cytogenetic Karyotyping Kits | Analysis of chromosomal number and structure in metaphase cells. | Diagnosing Turner syndrome (45,X) and other structural X-chromosome rearrangements [18] [19]. |

| Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) ELISA | Quantifying serum AMH levels as a marker of ovarian reserve. | Used as a correlative biochemical marker in genetic studies to assess ovarian function status [21] [4]. |

| Cell Culture Media for Lymphocytes | Short-term culture of peripheral blood cells to obtain metaphase chromosomes for karyotyping. | Essential for the initial cytogenetic analysis in the POI diagnostic workflow [19]. |

| Picfeltarraenin IA | Picfeltarraenin IA | Autophagy Inducer For Research | Picfeltarraenin IA is a natural triterpenoid for cancer & autophagy research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Aristolactam A IIIa | Aristolactam A IIIa, MF:C16H11NO4, MW:281.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Genetic Challenges in POI Research

Q1: What is the fundamental clinical and genetic distinction between syndromic and non-syndromic POI?

A1: The primary distinction lies in the presence of extra-ovarian symptoms.

- Non-Syndromic POI: The ovarian dysfunction is an isolated finding. Patients typically present with secondary amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea before age 40 and elevated Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH >25 IU/L), without other associated health issues pointing to a broader syndrome [4] [6].

- Syndromic POI: Ovarian insufficiency is one feature of a multi-system genetic disorder. Examples include Turner syndrome (associated with short stature and cardiac anomalies) and Fragile X premutation syndrome (which can also cause tremor/ataxia and intellectual disability in offspring) [1] [6].

Q2: What proportion of POI cases remain idiopathic, and why is this a major research challenge?

A2: Recent large-scale studies show the idiopathic fraction is shrinking but remains significant. A 2024 study found 36.9% of cases were idiopathic, a substantial decrease from historical cohorts where this figure was 72.1% [1]. This shift is largely due to improved genetic diagnostics. The challenge of idiopathic POI stems from its extreme genetic heterogeneity, the likely role of oligogenic inheritance (where variants in multiple genes act together), and the potential contribution of epigenetic factors and environmental toxicants not captured by standard genetic panels [22] [9] [6].

Q3: What are the key overlapping genetic pathways between syndromic and non-syndromic forms?

A3: Research reveals critical shared biological pathways, indicating common functional networks. The most prominent overlapping pathway is DNA repair and meiotic recombination [22] [9]. Genes in this pathway, such as MCM8, MCM9, SPIDR, HFM1, and several Fanconi Anemia genes (e.g., FANCA, FANCM), can cause both syndromic and non-syndromic POI. Other overlapping pathways include folliculogenesis (e.g., GDF9, BMP15), mitochondrial function, and transcriptional regulation [22] [9] [6].

Q4: How does establishing a genetic diagnosis impact patient management beyond fertility?

A4: A genetic diagnosis is critical for personalized medicine. In one large study, 37.4% of patients with a genetic diagnosis had variants in genes also associated with tumor/cancer susceptibility (e.g., BRCA2), necessitating lifelong monitoring [22]. Furthermore, in 8.5% of diagnosed cases, POI was the only initial symptom of a multi-organ genetic disease, guiding comprehensive health screening and management [22].

Q5: What is the recommended genetic testing workflow for a new POI patient?

A5: The 2024 international evidence-based guideline recommends a tiered approach [4]:

- First-line Tests: Karyotype and FMR1 premutation testing.

- Next-Step Diagnosis: If first-line tests are normal, proceed with Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) or a targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) panel covering known POI genes. WES is particularly effective for adolescents and those with a family history [23].

- Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis: This should be performed on WES or NGS data, as it can increase diagnostic yield [23].

Troubleshooting Guides for Genetic Diagnosis

Problem: Low Diagnostic Yield in a Well-Phenotyped POI Cohort

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Gene Coverage. Standard panels may miss newly discovered genes.

- Cause 2: Over-reliance on Monogenic Models. The etiology may involve variants in more than one gene.

- Solution: Investigate an oligogenic model. Look for potential digenic or polygenic interactions by analyzing variants in genes from the same biological pathway (e.g., two different DNA repair genes) [6].

- Cause 3: Variant Filtering Stringency. Overly strict filtering may discard pathogenic non-canonical variants.

- Solution: Manually review Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS) in known POI genes, especially non-canonical splice sites or deep intronic variants. Seek functional validation for top candidates [9].

Problem: Validating the Pathogenicity of a Novel Variant

Experimental Protocol: Functional Validation in a DNA Repair Gene

- Background: A novel missense variant is identified in a DNA repair gene (e.g., MCM8). In silico predictions are conflicting.

- Objective: To determine if the variant compromises DNA repair function.

- Materials:

- Patient-derived lymphocytes or engineered cell lines (e.g., HEK293, HeLa) with the variant.

- Control cell lines (isogenic wild-type).

- Mitomycin C (MMC), a DNA cross-linking agent.

- Immunofluorescence microscopy reagents (antibodies for γH2AX, RAD51).

- Comet assay kit.

- Methodology:

- Treat Cells: Expose patient and control cell lines to a low dose of MMC (e.g., 10-50 nM) for 24 hours. Include an untreated control.

- Assay DNA Damage:

- Comet Assay (Single-Cell Gel Electrophoresis): Perform under alkaline conditions to detect single and double-strand breaks. A significant increase in tail moment in variant cells indicates elevated basal and MMC-induced DNA damage.

- Immunofluorescence for DNA Repair Foci: Stain for γH2AX (a marker of DNA double-strand breaks) and RAD51 (a marker of homologous recombination). Quantify the number of foci per nucleus. Variant cells should show persistent γH2AX foci and reduced RAD51 foci post-treatment, indicating defective repair [22].

- Measure Chromosomal Instability: Perform metaphase spread analysis on lymphocytes after MMC exposure. A higher frequency of chromosomal gaps, breaks, and radial figures in patient cells confirms hypersensitivity to clastogenic agents and a defective DNA repair phenotype [22].

- Interpretation: The variant is classified as likely pathogenic if the cells show clear hypersensitivity to MMC, evidenced by increased DNA damage in the comet assay, impaired repair focus formation, and elevated chromosomal breakage.

Quantitative Data on POI Genetics

Table 1: Diagnostic Yields from Recent Genetic Studies in POI

| Study / Cohort Description | Cohort Size | Overall Genetic Diagnostic Yield | Key Genes and Pathways Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large WES Cohort (Nature Med, 2023) [9] | 1,030 patients | 23.5% (242/1030) | Meiosis/HR genes (48.7%), Mitochondrial genes, Novel candidates (LGR4, KASH5, ZP3) |

| Targeted & WES Cohort (EBioMedicine, 2022) [22] | 375 patients & 70 families | 29.3% | DNA repair/meiosis (37.4%), Follicular growth (35.4%), Tumor susceptibility |

| Russian Adolescent Cohort (Front. Endocrinol., 2025) [23] | 63 patients (<18 yrs) | 23.8% (monogenic) | FMR1, STAG3, NOBOX, MCM8, CNVs in BNC1, CPEB1 |

| Etiology Shift Analysis (PMC, 2025) [1] | 111 patients (contemporary) | N/A (Etiology breakdown) | Iatrogenic (34.2%), Autoimmune (18.9%), Genetic (9.9%), Idiopathic (36.9%) |

Table 2: Overlapping Gene Families in Syndromic and Non-Syndromic POI

| Gene Family / Pathway | Syndromic POI Examples | Non-Syndromic POI Examples | Primary Ovarian Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Repair & Meiosis | BLM (Bloom syndrome), FANC genes (Fanconi anemia) [9] | MCM8, MCM9, HFM1, MSH4 [22] [9] | Meiotic recombination, DNA double-strand break repair, genomic integrity in oocytes |

| Transcription Regulation | NOBOX (associated with hearing loss) [6] | NOBOX, FIGLA [22] [6] | Regulation of oocyte-specific gene expression, folliculogenesis |

| Mitochondrial Function | TWNK (Perrault syndrome), POLG (SCAE, PEO) [9] | AARS2, HARS2, CLPP [9] | Oocyte energy production, apoptosis regulation |

| Folate Metabolism | MTHFR (associated with neural tube defects) [6] | MTHFR polymorphisms [6] | Follicular development and oocyte quality |

Visualization: Overlapping Genetic Networks

The following diagram illustrates the core genetic and cellular pathways overlapping in syndromic and non-syndromic POI, highlighting shared genes and the points where idiopathic forms present research challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for POI Genetic Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Comprehensive analysis of the protein-coding genome to identify novel and rare variants. | Discovery of novel POI-associated genes (e.g., HELQ, KASH5) in large patient cohorts [9] [23]. |

| Custom Targeted NGS Panels | Focused, cost-effective sequencing of a curated set of known and candidate POI genes. | High-throughput diagnostic screening for established genes (e.g., panels covering 88+ POI genes) [22]. |

| Mitomycin C (MMC) | DNA cross-linking agent used to induce replication stress and DNA double-strand breaks. | Functional validation of DNA repair gene variants by assessing chromosomal breakage sensitivity in patient lymphocytes [22]. |

| Anti-γH2AX & Anti-RAD51 Antibodies | Immunofluorescence detection of DNA damage and homologous recombination repair foci. | Quantifying the efficiency of DNA repair in cells carrying a VUS in a meiosis-related gene [22]. |

| Copy Number Variation (CNV) Callers | Bioinformatics tools to detect exon-level deletions/duplications from NGS data. | Identifying pathogenic CNVs in genes like BNC1 and FSHR that are missed by SNV analysis [23]. |

| DL-Methionine-d4 | DL-Methionine-3,3,4,4-d4 (98%)|Stable Isotope | |

| GW4869 | GW4869, MF:C30H30Cl2N6O2, MW:577.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Genomic Technologies and Their Diagnostic Yield in Idiopathic POI

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (array-CGH) has established itself as a cornerstone technology for detecting copy number variants (CNVs) across the genome. This powerful molecular technique provides high-resolution detection of chromosomal deletions and duplications that underlie various genetic disorders. Within the specific research context of idiopathic Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI), defined as the loss of ovarian function before age 40 with a prevalence of 1-2% in women, array-CGH has proven particularly valuable for identifying genetic anomalies where standard karyotyping and FMR1 premutation testing yield no answers [7] [24]. Historically, the diagnosis of POI remained elusive in approximately 70% of cases, categorized as idiopathic because no specific cause could be identified [7]. The integration of array-CGH into genetic research workflows has significantly addressed this diagnostic gap by enabling genome-wide screening for submicroscopic CNVs that escape detection by conventional cytogenetic methods. This technical support document provides comprehensive guidance on optimizing array-CGH methodologies specifically for POI research, addressing common experimental challenges, and implementing robust troubleshooting protocols to enhance research outcomes in idiopathic POI genetic diagnosis.

Technical Foundations: How Array-CGH Works

Array-CGH functions on the principle of competitive hybridization between test and reference DNA samples to a microarray platform containing thousands of immobilized DNA probes. In standard implementation, patient DNA and reference DNA are labeled with different fluorescent dyes (typically Cy5 and Cy3, respectively) [25]. The labeled samples are mixed in equal quantities and hybridized to the array, where they competitively bind to complementary probe sequences. Following hybridization and washing, the array is scanned to measure fluorescence intensity at each probe location [25].

The resulting fluorescence ratio between the two dyes at each probe indicates relative copy number: balanced fluorescence suggests normal copy number, increased test DNA signal indicates duplication, and decreased test DNA signal indicates deletion [25]. This methodology represents a significant advancement over traditional cytogenetic techniques, offering substantially higher resolution (typically detecting variants as small as 50-200 kb compared to the 5 Mb resolution of standard karyotyping) and enabling genome-wide assessment without prior hypothesis about specific chromosomal regions [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Genomic Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Resolution | CNV Detection | Balanced Rearrangements | Sequence Variants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karyotyping | ~5 Mb | Limited (large changes only) | Yes | No |

| Array-CGH | 50-200 kb | Yes | No | No |

| SNP Array | Higher than array-CGH | Yes | No (but detects UPD and consanguinity) | Limited |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Single base | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Array-CGH Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core array-CGH workflow, from sample preparation to final data analysis:

Detailed Methodology for POI Research Applications

For research on idiopathic Premature Ovarian Insufficiency, the following protocol has been specifically optimized based on recent studies that successfully identified CNVs in POI patients [7]:

Sample Quality Control and DNA Preparation

- Obtain high-quality genomic DNA from peripheral blood samples using standardized extraction kits (e.g., QIAsymphony DNA midi kits) [7]

- Assess DNA purity and concentration via spectrophotometry; acceptable A260/280 ratio: 1.8-2.0

- Ensure DNA integrity through gel electrophoresis; minimal degradation required

- Input requirement: 0.5-2.5 μg of genomic DNA per labeling reaction [26]

DNA Labeling and Hybridization (Optimized for Agilent Platform)

- Utilize oligonucleotide array-CGH with SurePrint G3 Human CGH Microarray 4×180 K technology [7]

- Label test and reference DNA with Cy5 and Cy3 respectively using genomic DNA labeling kits

- Perform fragmentation of labeled DNA at 60°C for 30 minutes

- Mix labeled test and reference samples with Cot-1 DNA and hybridization buffer

- Hybridize to microarray for 24-40 hours at 65°C with rotation [7]

Data Acquisition and Bioinformatics Analysis

- Scan arrays using dual-laser scanner (e.g., Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner)

- Extract feature data using appropriate software (e.g., Agilent Feature Extraction software)

- Analyze CNVs using specialized bioinformatics tools (e.g., Agilent CytoGenomics software v5.0 with Cartagenia Bench Lab CNV software v5.1) [7]

- Implement minimum CNV detection threshold of 60 kb for optimal resolution [7]

- Annotate identified CNVs using population databases (gnomAD, DGV) and clinical databases (DECIPHER, ClinVar) [7]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Frequently Encountered Technical Issues and Solutions

Table 2: Array-CGH Troubleshooting Guide for POI Research

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solution | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| High background noise | Incomplete washing, insufficient blocking, dye precipitation | Increase stringency of washes, validate Cot-1 DNA quality, filter hybridization solution | Use fresh hybridization buffer, optimize wash temperatures, implement quality control checks |

| Channel bias (dye effect) | Differential dye incorporation, probe-specific dye biases | Implement dye-swap experiments, use validated labeling kits with optimized dyes [27] | Employ balanced block experimental designs instead of reference designs [28] |

| Poor signal-to-noise ratio | Suboptimal DNA labeling, insufficient DNA input, degraded samples | Use enzymatic random primed amplification methods, quantify DNA accurately pre-labeling [27] | Verify DNA quality before processing, use specialized kits for suboptimal samples (e.g., FFPE) [26] |

| Inconsistent replication | Array-to-array variability, batch effects in processing | Process case and control samples simultaneously, randomize arrays across experimental batches | Include technical replicates, implement rigorous quality control metrics (DLRSD, SNR) [26] |

| Artifactual CNV calls | DNA quality issues, sample mix-ups, reference sample variability | Replicate findings with alternative method (MLPA, qPCR), use matched reference samples | Use standardized reference samples (e.g., pooled reference), process samples in same batch [28] |

Optimizing Experimental Design for POI Studies

Research indicates that alternative experimental designs can significantly enhance efficiency and statistical power in array-CGH studies:

Reference Design Limitations

- Traditional reference designs allocate half of all hybridizations to reference samples not of biological interest [28]

- This approach fails to account for probe-specific dye biases that can affect copy number estimates [28]

- Variance component analyses demonstrate that subject-to-subject variance is typically nearly twice the array-to-array variance, suggesting resources are better allocated to additional biological samples rather than reference replicates [28]

Enhanced Design Strategies

- Balanced block designs: When comparing two groups (e.g., POI patients vs. controls), hybridize one sample from each group on the same array [28]

- Balanced incomplete-block designs: For studies with multiple groups, ensure balanced dye labeling across samples despite not all groups fitting on each array [28]

- Off-chip reference approaches: Process reference samples separately from experimental arrays to double throughput without sacrificing data quality when samples are processed simultaneously [28]

FAQs: Addressing Researcher Questions on Array-CGH in POI

Q1: What detection sensitivity can be expected for CNVs in POI research using array-CGH? Array-CGH reliably detects CNVs down to approximately 60 kb when using modern high-density platforms (e.g., 4x180K arrays), with some platforms offering even higher resolution [7]. However, detection limits depend on probe density in specific genomic regions. For POI research, this resolution is sufficient to identify clinically relevant CNVs but may miss smaller single-exon deletions/duplications that require techniques like MLPA.

Q2: How does array-CGH compare to next-generation sequencing (NGS) for POI genetic diagnosis? Array-CGH and NGS provide complementary information in POI diagnostics. Recent studies combining both technologies in the same idiopathic POI patients demonstrated that array-CGH identified causal CNVs in 3.6% of patients, while NGS identified causal SNVs/indels in 28.6% of patients [7] [24]. The combined diagnostic yield reached 57.1% when including variants of uncertain significance, highlighting the value of a multi-technology approach [7].

Q3: What are the specific challenges when working with limited DNA samples, and how can they be addressed? Limited DNA availability, common with rare patient cohorts like POI, presents significant challenges for array-CGH. Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) techniques enable successful analysis with as little as 1 ng of input DNA while maintaining detection accuracy for known chromosomal aberrations [26]. For severely fragmented DNA (e.g., from FFPE samples), fragmentation to ~400 bp average size still produces comparable results to intact DNA when using appropriate WGA methods [26].

Q4: Which chromosomal regions require special attention in POI array-CGH studies? While array-CGH assesses the entire genome, particular attention should be paid to the X chromosome, given its established role in POI pathogenesis. However, research indicates that submicroscopic X chromosomal CNVs may play a more limited role than previously hypothesized, with one large study finding no major association between Xq21.3 CNVs and POI after rigorous validation [29]. This underscores the importance of genome-wide analysis rather than targeted X chromosome assessment.

Q5: How can the limitations of array-CGH regarding balanced rearrangements be addressed in POI research? Array-CGH cannot detect balanced translocations or inversions, which represent a known limitation for comprehensive genetic assessment [25]. In POI research, where these balanced rearrangements can contribute to pathogenesis, complementary karyotyping should be performed alongside array-CGH, particularly for patients with syndromic features or family histories suggestive of chromosomal rearrangements.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Array-CGH in POI Research

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GenomePlex WGA Kit | Whole genome amplification from limited DNA | Enables analysis from 1-100 ng input DNA; crucial for rare POI cohorts [26] |

| BioPrime Total Array CGH System | Genomic DNA labeling with optimized dyes | Reduces channel bias; improves signal-to-noise ratios [27] |

| Agilent Genomic DNA Labeling Kit PLUS | Fluorophore incorporation for hybridization | Compatible with Agilent platform; optimized for 2.0-2.5 μg DNA input [26] |

| Agilent SurePrint G3 CGH Microarrays | High-resolution CNV detection | 4x180K format provides optimal balance of resolution and cost for POI studies [7] |

| BioPrime Total FFPE System | DNA labeling from suboptimal samples | Specifically designed for challenging samples like FFPE tissues [27] |

The strategic implementation of array-CGH technology has fundamentally transformed the research landscape for idiopathic Premature Ovarian Insufficiency, moving a substantial proportion of cases from the idiopathic category to genetically explained diagnoses. Through attention to experimental design considerations, appropriate troubleshooting protocols, and integration with complementary technologies like NGS, researchers can continue to leverage array-CGH to unravel the genetic architecture of POI. The optimization strategies presented in this technical guide address historical limitations of the technology while providing frameworks for enhancing detection accuracy, managing limited samples, and interpreting results in the context of POI pathogenesis. As genetic research progresses, array-CGH remains an essential component in the comprehensive genomic toolkit required to dissect this complex and clinically significant disorder.

Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) is a clinically heterogeneous disorder characterized by the loss of ovarian function before age 40, affecting approximately 1% of the female population [7] [30]. Despite established associations with genetic, autoimmune, and iatrogenic factors, the etiology of POI remains elusive in a significant proportion of cases, classified as idiopathic. Genetic causes account for an estimated 20-25% of POI cases, but this figure is likely an underestimation given the limitations of previous diagnostic approaches [31]. The transition to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies has revolutionized the molecular diagnosis of idiopathic POI, enabling simultaneous analysis of multiple known and candidate genes. This technical guide explores the implementation, optimization, and troubleshooting of NGS panels within the context of POI research, providing a framework for researchers and clinical scientists to enhance diagnostic yield and expand our understanding of the genetic architecture underlying this complex disorder.

Technical Foundation: NGS Panel Design and Workflow

Core Components of an NGS Panel for POI Research

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for POI NGS Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit, SureSelect XT-HS reagents, HaloPlex Target Enrichment System | Fragments and prepares genomic DNA for sequencing with adapter ligation and barcode incorporation |

| Target Enrichment | Custom Ampliseq Panels, SurePrint G3 CGH Microarray, Haloplex ICCG panel | Selectively captures genomic regions of interest to enrich POI-associated genes |

| Sequencing | Ion Torrent PGM System, Illumina NextSeq 500, Ion S5 Sequencing Kit | Performs massively parallel sequencing of enriched libraries |

| Variant Calling | Torrent Variant Caller, GATK Unified Genotyper, SAMtools | Identifies sequence variations from aligned sequencing data |

| Variant Annotation | Ion Reporter, Varsome, Ensembl VEP | Characterizes identified variants with population frequency and functional impact data |

Standardized Experimental Protocol for POI Gene Panel Sequencing

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for NGS panel sequencing in POI research, compiled from multiple established methodologies [7] [32] [33]:

DNA Extraction and Quality Control: Extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood using validated extraction kits (e.g., QIAsymphony DNA midi kits). Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Quant-iT PicoGreen) and assess quality via spectrophotometry. Input requirement: 50-225 ng of high-quality DNA (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0).

Library Preparation: Utilize targeted amplification (e.g., Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit Plus) or hybrid capture-based (e.g., SureSelectXT) approaches. For amplification-based methods, employ multiplexed PCR with target-specific primers covering exonic regions and splice sites of POI-associated genes. Incubation conditions: 99°C for 2 minutes, followed by 19 cycles of 99°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 4 minutes.

Template Preparation and Sequencing: Perform emulsion PCR (Ion Torrent) or bridge amplification (Illumina) depending on platform specification. For Ion Torrent systems, enrich template-positive Ion Sphere Particles using the Ion OneTouch ES system. Sequence enriched libraries on appropriate platforms (Ion PGM, Illumina NextSeq) using manufacturer-recommended sequencing kits.

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline:

- Base Calling and Demultiplexing: Use platform-specific software (Torrent Suite, MiSeq Reporter).

- Sequence Alignment: Map reads to reference genome (hg19/GRCh37) using optimized aligners (TMAP, BWA-MEM).

- Variant Calling: Identify SNPs, indels using variant callers (Torrent Variant Caller, GATK UnifiedGenotyper) with minimum coverage depth of 30x.

- Variant Annotation and Filtering: Annotate variants using curated databases (gnomAD, ClinVar, HGMD) and prediction algorithms (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD).

Figure 1: End-to-End Workflow for NGS Panel Analysis in POI Research

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Low Coverage and Incomplete Target Enrichment

Problem: Inadequate sequencing depth (<30x) for critical regions, resulting in potential missed variants.

Solutions:

- Verify DNA Input Quality: Degraded DNA or insufficient input quantity directly impacts library complexity. Always use fluorometric quantification rather than spectrophotometry alone.

- Optimize Hybridization Conditions: For capture-based approaches, increase hybridization time to 16+ hours and optimize temperature conditions [34].