Viral vs. Non-Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development

This article provides a detailed comparison of viral and non-viral somatic gene therapy (SMGT) methods for researchers and drug development professionals.

Viral vs. Non-Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of viral and non-viral somatic gene therapy (SMGT) methods for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational biology of leading vector platforms, their methodological applications in clinical settings, strategies for troubleshooting critical challenges like immunogenicity and manufacturing, and a direct validation of their relative strengths and weaknesses. Synthesizing the latest clinical data and technological advances, the review offers a strategic framework for selecting and optimizing gene delivery systems to accelerate therapeutic development from the lab to the clinic.

Understanding Gene Delivery Vectors: Core Principles and System Classifications

The remarkable progress in somatic gene therapy over the past decades has fundamentally shifted treatment paradigms for numerous genetic disorders, offering potential cures for conditions previously considered untreatable. At the heart of this therapeutic revolution are the delivery vectors—sophisticated vehicles designed to transport therapeutic genetic material into target cells. These vectors broadly fall into two categories: viral vectors, which harness the natural efficiency of viruses, and non-viral vectors, which employ synthetic or biological compounds for gene delivery [1] [2]. The choice between viral and non-viral delivery systems represents a critical decision point in therapeutic development, balancing factors including delivery efficiency, cargo capacity, immunogenicity, and manufacturing scalability.

The field has witnessed significant milestones, with 35 vector-based therapies currently approved globally. Viral vectors dominate the approved therapies landscape, constituting 29 of these treatments, while non-viral approaches account for the remaining 6 approved products [1] [3]. This distribution reflects the current state of vector technology while highlighting the growing importance of non-viral platforms. This guide provides a comprehensive, objective comparison of these delivery systems, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental applications, and practical implementation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Vector Platforms

Viral Vector Systems: Established Workhorses of Gene Therapy

Viral vectors leverage the natural ability of viruses to efficiently deliver genetic material into cells. The three predominant viral platforms—lentivirus (LV), adenovirus (Ad), and adeno-associated virus (AAV)—each offer distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different therapeutic applications [1] [3].

Lentiviral (LV) vectors, derived from retroviruses, are primarily utilized in ex vivo gene therapy applications, particularly in chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies and hematopoietic stem cell gene therapies. Their key advantage is stable genomic integration, enabling long-term transgene expression in dividing cells. Approved LV-based therapies include Kymriah for leukemia, Zynteglo for β-thalassemia, and Libmeldy for metachromatic leukodystrophy [1] [3]. However, this integration capacity carries the risk of insertional mutagenesis, as evidenced by rare cases of blood cancer development following treatment with Skysona [3].

Adenoviral (Ad) vectors feature a large double-stranded DNA genome capable of accommodating payloads up to 36 kb, making them suitable for delivering large genetic sequences. They provide high transduction efficiency and robust transient transgene expression without genomic integration. Their primary limitation is significant immunogenicity, which can trigger potent inflammatory responses and has largely confined their clinical use to oncology and vaccine applications [3] [2]. Early successes include Gendicine and Oncorine for head and neck cancers [1].

Adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors have emerged as the leading platform for in vivo gene therapy due to their favorable safety profile, including non-pathogenicity and primarily episomal persistence that reduces genotoxicity risks. Their ability to transduce non-dividing cells and provide long-term transgene expression has led to multiple approved therapies, including Luxturna for inherited retinal dystrophy, Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy, and Hemgenix for hemophilia B [1] [4] [3]. A significant limitation is their constrained cargo capacity (~4.7 kb), though innovative dual-vector approaches are being developed to deliver larger genes [3].

Non-Viral Vector Systems: Emerging Safe Alternatives

Non-viral vectors have gained substantial momentum as safer, more scalable alternatives to viral platforms, particularly following the successful deployment of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) in mRNA COVID-19 vaccines [3] [5].

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) represent the most advanced non-viral platform, comprising ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipids that self-assemble into vesicles capable of encapsulating and protecting nucleic acids. LNPs efficiently deliver their payload through endocytic pathways and have enabled approved therapies like Patisiran for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis [1] [3]. They are also being investigated for CRISPR-Cas9 delivery, as demonstrated by NTLA-2002 for hereditary angioedema [3]. Key advantages include large cargo capacity, low immunogenicity, and scalable manufacturing, though challenges remain with lower transfection efficiency in certain tissues and predominant liver-focused biodistribution [3] [5].

N-Acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) conjugates represent a specialized approach for liver-targeted delivery of RNA therapeutics. GalNAc, a ligand for the asialoglycoprotein receptor highly expressed on hepatocytes, enables efficient receptor-mediated uptake of conjugated RNA molecules. This platform has enabled multiple FDA-approved drugs, including Givlaari for acute hepatic porphyria, Oxlumo for primary hyperoxaluria type 1, and Leqvio for hypercholesterolemia [1] [3]. The primary advantage is tissue-specific targeting with subcutaneous administration, though application is currently restricted to hepatic conditions [3].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Gene Therapy Vector Platforms

| Vector Platform | Cargo Capacity | Integration Profile | Immunogenicity | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lentivirus (LV) | ~8 kb | Stable integration | Moderate | Ex vivo therapies (CAR-T, hematopoietic stem cells) | Long-term expression in dividing cells | Risk of insertional mutagenesis |

| Adenovirus (Ad) | Up to 36 kb | Episomal | High | Cancer therapy, vaccines | Large cargo capacity, high transduction efficiency | Strong immune response |

| AAV | ~4.7 kb | Predominantly episomal | Low to moderate | In vivo gene therapy (neuromuscular, ocular, hepatic) | Excellent safety profile, transduces non-dividing cells | Limited cargo capacity, pre-existing immunity |

| LNP | >10 kb | Non-integrating | Low | siRNA, mRNA, CRISPR delivery | Large cargo capacity, scalable manufacturing | Mostly liver tropism, lower efficiency in some tissues |

| GalNAc | Variable | Non-integrating | Very low | Liver-targeted RNA therapeutics | High tissue specificity, subcutaneous administration | Restricted to hepatic applications |

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Comparison of Delivery Efficiency

Rigorous evaluation of vector performance requires standardized metrics across multiple parameters. The following table synthesizes experimental data from preclinical and clinical studies to enable direct comparison of key performance indicators.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Vector Platforms in Preclinical and Clinical Applications

| Vector Platform | Transduction Efficiency In Vivo | Expression Duration | Therapeutic Dose Range | Clinical Success Rate* | Manufacturing Titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV (ex vivo) | >80% (in modified cells) | Long-term (years) | 1-10×10^6 transduced cells/kg | High (>70% in approved therapies) | 10^8-10^9 TU/mL |

| Ad | 60-95% (varies by tissue) | Transient (weeks) | 10^11-10^13 VP | Moderate in oncology | 10^11-10^12 VP/mL |

| AAV | 20-90% (serotype-dependent) | Long-term (years) | 10^11-10^15 VP (route-dependent) | High (>80% in approved therapies) | 10^13-10^14 VG/L |

| LNP | 15-60% (liver) | Transient (days-weeks) | 0.1-1.0 mg/kg mRNA | High in approved indications | Highly scalable |

| GalNAc | 40-80% (hepatocytes) | Transient (weeks-months) | 1-10 mg/kg (subcutaneous) | High in approved indications | Highly scalable |

*Clinical success rate defined as percentage of patients achieving primary efficacy endpoint in registrational trials for approved products.

Key Experimental Findings by Vector Class

Viral Vector Performance: AAV vectors demonstrate particularly impressive long-term transduction in clinical applications, with sustained transgene expression documented for over 5 years following single administration in retinal and neuromuscular disorders [4]. However, dose-dependent immune responses remain a significant concern, particularly with high-dose systemic administration [6]. Recent clinical data reveal that both innate and adaptive immune responses to AAV capsids can substantially impact therapeutic efficacy, with pre-existing neutralizing antibodies excluding approximately 30-50% of potential patients from systemic AAV therapy trials [6].

LV vectors exhibit remarkable ex vivo transduction efficiency, with studies demonstrating >80% CAR integration in T-cells across multiple clinical trials [1]. The recent development of LV-based therapies for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia has demonstrated sustained hemoglobin production years after treatment, highlighting their potential for durable effect [1] [3].

Non-Viral Vector Performance: LNP delivery systems have shown dose-dependent transfection efficiency in preclinical models, with Tessera Therapeutics reporting approximately 42% CAR integration in ex vivo T-cell editing studies using proprietary LNPs [5]. Notably, their technology achieved multiplexed knock-out at TRAC and B2M loci with >88% efficiency while simultaneously enabling CAR integration at 20% efficiency [5].

GalNAc-conjugated therapies demonstrate exceptional hepatocyte specificity, with clinical studies showing >80% target gene knockdown in the liver at doses as low as 1-10 mg/kg administered subcutaneously [3]. This approach minimizes off-target effects while maintaining potent on-target activity.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Assessment of Vector Performance

To ensure reproducible evaluation across vector platforms, researchers should implement standardized experimental protocols for key performance parameters.

Protocol 1: In Vivo Transduction Efficiency Assessment

- Objective: Quantify vector-mediated gene delivery efficiency in target tissues

- Procedure:

- Administer vectors via relevant route (IV, IT, IM, etc.) at standardized doses

- Harvest target tissues at predetermined endpoints (e.g., 7, 14, 28 days post-administration)

- Process tissues for:

- qPCR/RT-qPCR: Quantify vector genome copies and transgene expression

- Immunohistochemistry: Localize and quantify transgene expression

- Western Blot: Confirm functional protein production

- Calculate transduction efficiency as percentage of target cells expressing transgene

Protocol 2: Immune Response Profiling

- Objective: Characterize innate and adaptive immune responses to vector administration

- Procedure:

- Collect serial blood samples pre- and post-vector administration

- Analyze samples for:

- Cytokine profiling (IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α) via ELISA or multiplex assays

- Neutralizing antibody detection using in vitro transduction inhibition assays

- T-cell responses via ELISpot for IFN-γ secretion upon capsid stimulation

- Perform immunohistochemistry on tissues for immune cell infiltration assessment

Protocol 3: Biodistribution and Persistence Studies

- Objective: Track vector distribution and transgene persistence over time

- Procedure:

- Administer radiolabeled or barcoded vectors

- Quantify vector genomes in target and non-target tissues at multiple timepoints

- Assess transgene expression duration via longitudinal imaging (if reporter included) or terminal tissue analysis

- For integrating vectors, analyze integration sites using LAM-PCR or next-generation sequencing methods

Specialized Methodologies by Vector Class

Viral Vector-Specific Protocols:

- Empty Capsid Contamination Assessment: Critical for AAV preparations, performed via analytical ultracentrifugation or ELISA to quantify ratio of full to empty particles, which impacts potency and immunogenicity [6].

- Replication-Competent Virus Testing: Essential safety assessment for all viral vector lots via co-culture assays with permissive cell lines and PCR detection.

- Serotype-Specific Tropism Profiling: Comparative evaluation of different AAV serotypes (AAV1, AAV2, AAV8, AAV9, etc.) for tissue-specific transduction efficiency using barcoded libraries [4] [7].

Non-Viral Vector-Specific Protocols:

- LNP Characterization: Comprehensive physical assessment including particle size (dynamic light scattering), encapsulation efficiency (Ribogreen assay), polydispersity index, and zeta potential.

- Endosomal Escape Efficiency: Quantification of functional delivery using split-luciferase or fluorophore-based systems that require cytosolic delivery for signal generation.

- Tropism Modification Assessment: Evaluation of targeting ligand incorporation through comparative biodistribution studies in relevant animal models.

Visualization of Key Mechanisms and Workflows

Viral Vector Mechanism and Immune Recognition

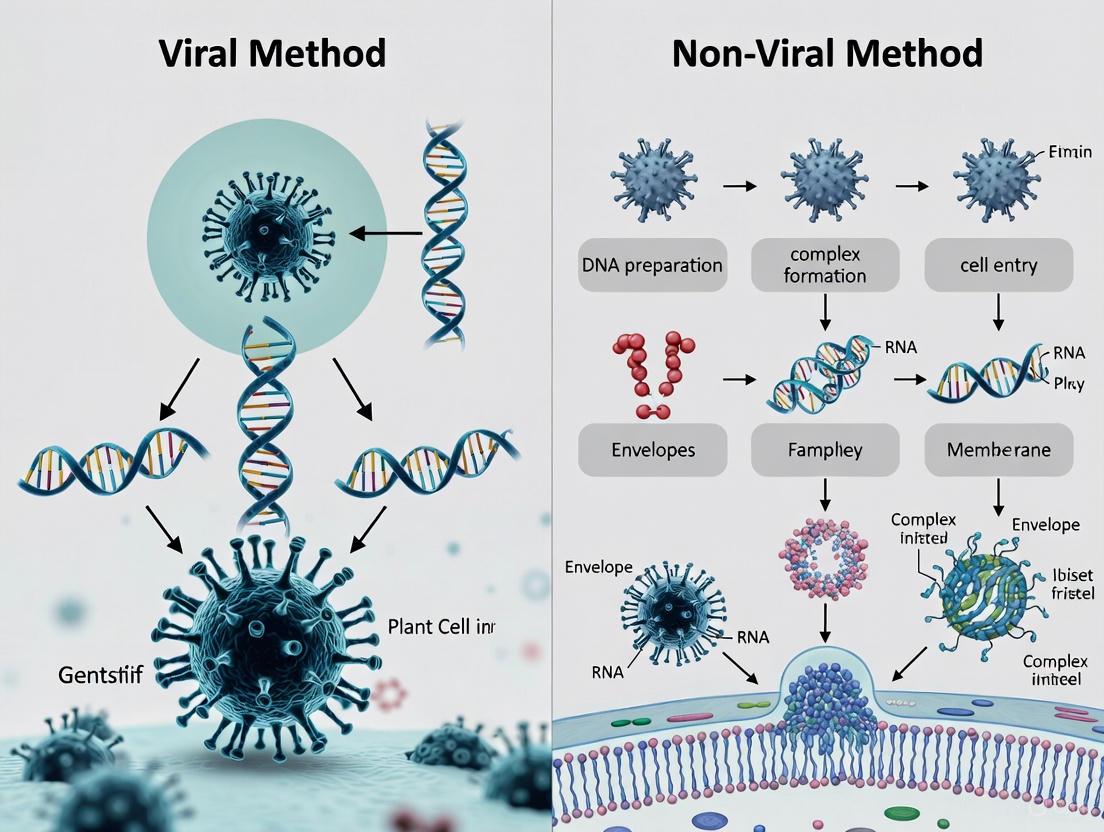

The following diagram illustrates the intracellular trafficking mechanisms of viral vectors and key immune recognition pathways that impact therapeutic efficacy.

Diagram 1: Viral vector mechanisms and immune recognition. This diagram illustrates the intracellular trafficking of viral vectors (top) and the immune recognition pathways (bottom) that can limit therapeutic efficacy, including TLR9-mediated recognition of CpG motifs and subsequent neutralizing antibody production.

Non-Viral Vector Delivery Workflow

The following diagram outlines the complete workflow for non-viral vector delivery, from formulation to therapeutic action.

Diagram 2: Non-viral vector delivery workflow. This diagram illustrates the complete pathway for non-viral vector delivery, including LNP formulation (left), cellular delivery and processing (center), and therapeutic action mechanisms (right), with GalNAc-targeted delivery as a specialized approach.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful gene therapy research requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for specific vector platforms. The following table details essential research tools for investigating viral and non-viral delivery systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Therapy Vector Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Packaging Plasmids | Essential components for recombinant viral vector production | Optimize ratio for maximum titer and full capsid percentage | AAV, LV, Ad vector production |

| Cell Lines for Production | Factory cells for viral vector generation | Select for permissiveness, scalability, and low adventitious agents | HEK293, Sf9 systems for AAV production |

| Purification Systems | Isolation and concentration of vectors from crude lysates | Balance purity, yield, and activity preservation | AAV purification using affinity or ion-exchange chromatography |

| Characterization Assays | Quality control and vector quantification | Standardize across batches for reproducibility | qPCR for genome titer, ELISA for capsid titer, TCID50 for infectivity |

| Ionizable Lipids | Core component of LNP formulations for nucleic acid encapsulation | Structure affects efficacy, biodegradability, and toxicity | SM-102, DLin-MC3-DMA for mRNA delivery |

| Targeting Ligands | Enable cell-specific delivery of non-viral vectors | Conjugation method impacts activity and stability | GalNAc for hepatocytes, peptide ligands for extrahepatic targeting |

| Animal Models | In vivo evaluation of biodistribution and efficacy | Consider species-specific tropism and immune responses | Mice, NHP for AAV studies; disease-specific models for efficacy |

| Akt-IN-18 | Akt-IN-18, MF:C19H14ClN5O2S, MW:411.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Mao-B-IN-31 | Mao-B-IN-31, MF:C16H14N2O2S, MW:298.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The evolving landscape of gene therapy vectors reflects a dynamic interplay between viral and non-viral platforms, each advancing to address persistent challenges. Viral vectors continue to dominate clinical applications, with ongoing innovations focused on capsid engineering to evade pre-existing immunity, tropism refinement for enhanced tissue specificity, and dual-vector systems to overcome cargo limitations [1] [6]. Non-viral platforms are rapidly evolving with novel ionizable lipids improving delivery efficiency beyond the liver, biodegradable formulations enhancing safety profiles, and modular design approaches enabling precise targeting of extrahepatic tissues [3] [5].

The future of somatic gene therapy delivery will likely witness increased convergence between viral and non-viral technologies, incorporating viral elements into synthetic vectors and applying non-viral principles to improve viral vector manufacturing. As both platforms mature, the selection criteria will increasingly focus on matching vector capabilities to specific therapeutic contexts—considering disease pathophysiology, target tissue accessibility, required expression level and duration, and patient-specific factors such as pre-existing immunity. This nuanced, application-driven approach to vector selection will ultimately expand the therapeutic landscape, bringing transformative treatments to broader patient populations across diverse genetic disorders.

Viral vectors are engineered viruses designed to deliver therapeutic genetic material into human cells, serving as a cornerstone of modern gene therapy [8]. By harnessing the innate ability of viruses to infect cells and introduce their genetic payload, scientists have developed powerful tools to treat a wide range of genetic disorders, cancers, and infectious diseases [9]. Among the various options available, three viral vector platforms have emerged as predominant in both research and clinical applications: lentiviruses (LV), adenoviruses (Ad), and adeno-associated viruses (AAV) [10] [11]. Each vector system possesses distinct biological characteristics, performance parameters, and application landscapes that researchers must carefully consider when designing gene therapy strategies [11]. The selection of an appropriate viral vector is critical not only for experimental success but also for clinical efficacy and safety, as mismatches between vector capabilities and therapeutic requirements can lead to failed experiments or adverse patient outcomes [10]. This guide provides a comprehensive, data-driven comparison of these three viral vector systems to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their experimental design and therapeutic development decisions.

Comparative Analysis of Key Vector Characteristics

The effective deployment of viral vectors in gene therapy requires a thorough understanding of their fundamental biological properties and performance capabilities. The table below summarizes the critical differentiating characteristics of AAV, lentiviral, and adenoviral vectors, enabling researchers to make informed decisions based on their specific experimental or therapeutic requirements.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of AAV, Lentivirus, and Adenovirus Vectors

| Characteristic | AAV | Lentivirus (LV) | Adenovirus (Ad) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Material | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) [12] | RNA [13] | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) [10] |

| Packaging Capacity | ~4.7 kb [10] [13] [12] | ~8 kb [10] [11] | Up to ~36 kb [10] |

| Genome Integration | Predominantly non-integrating (episomal) [13] [12] | Integrating [11] [13] | Non-integrating (episomal) [11] |

| Expression Kinetics | Slow onset, but long-term (months to years) [10] | Slow onset, stable long-term expression [10] | Rapid onset, transient expression (days to weeks) [10] [11] |

| Immunogenicity | Low [11] [13] | Low [10] | High [10] [11] |

| Tropism (Infection Range) | Broad, with serotype-specific targeting [12] | Broad (dividing and non-dividing cells) [11] [13] | Broad (dividing and non-dividing cells) [10] [9] |

| Primary Applications | In vivo gene therapy for monogenic diseases [13] [12] | Ex vivo cell engineering (e.g., CAR-T, HSCs) [10] [13] | Vaccines, oncolytic therapy, transient gene expression [10] [11] |

| Biosafety Level | BSL-1 [10] | BSL-2 [10] | BSL-2 [10] |

Critical Performance Differentiators

Packaging Capacity and Transgene Design: The limited ~4.7 kb capacity of AAV vectors presents significant constraints for delivering large genetic sequences, sometimes necessitating dual-vector approaches for larger genes [10] [12]. Lentiviral vectors offer a middle ground with approximately 8 kb capacity, while adenoviral vectors provide the most flexibility with the ability to accommodate large or multiple transgenes up to 36 kb [10] [11]. This capacity directly influences experimental design, particularly for complex expression cassettes requiring large regulatory elements or multiple transcriptional units.

Expression Duration and Stability: The persistence of transgene expression varies dramatically between vector systems, dictated by their fundamental biology. AAV vectors achieve long-term expression through episomal persistence in non-dividing cells, often lasting months to years [10]. Lentiviral vectors provide stable long-term expression through integration into the host genome, ensuring persistence through cell division [11]. Adenoviral vectors generate high-level but transient expression due to episomal maintenance and immune-mediated clearance of transduced cells, typically lasting days to weeks [10] [11].

Safety Considerations: AAV vectors demonstrate the most favorable safety profile with low immunogenicity and minimal risk of insertional mutagenesis due to their predominantly episomal persistence [10] [13]. Lentiviral vectors present a theoretical risk of insertional mutagenesis, though this is significantly lower than earlier retroviral vectors due to preferential integration into active transcriptional units [13]. Adenoviral vectors trigger robust immune responses that can eliminate transduced cells and complicate repeated administration, though this property can be advantageous in vaccine and oncolytic applications [10] [11].

Application-Specific Vector Selection Guide

The therapeutic or research objective represents the primary determinant in viral vector selection. Different disease targets, target tissues, and expression requirements necessitate careful matching with vector capabilities. The following table outlines optimal application domains for each vector system based on their inherent biological properties and documented clinical successes.

Table 2: Application-Based Vector Selection Guide

| Therapeutic/Research Area | Recommended Vector | Rationale and Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Neurological Disorders (e.g., Parkinson's, Alzheimer's) | AAV [10] | Ability to cross the blood-brain barrier; long-term expression in non-dividing neurons; multiple CNS-tropic serotypes (AAV9, AAVrh.10) [10] [12]. |

| Ophthalmic Diseases (e.g., LCA2) | AAV [10] [12] | Successful clinical application (Luxturna); low immunogenicity in immune-privileged eye; sustained expression in retinal cells [14] [12]. |

| Hematological Disorders & ex vivo Cell Therapy (e.g., SCID, CAR-T) | Lentivirus [10] [13] | Stable integration in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells ensures persistence in differentiated lineages; clinical success in β-thalassemia and CAR-T therapies [10] [13]. |

| Vaccine Development | Adenovirus [10] | Strong immunogenicity stimulates robust immune response; rapid, high-level antigen expression; successful platform for COVID-19 vaccines [10]. |

| Muscular Dystrophies | AAV [11] | Efficient transduction of muscle tissue; long-term expression in post-mitotic myofibers; clinical use of AAV9 in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy trials [11] [12]. |

| Oncolytic Virotherapy | Adenovirus [11] | Natural tropism for epithelial cells; cytotoxic effects in cancer cells; ability to engineer replication-competent variants for selective tumor lysis [11]. |

| Large Gene Delivery (>5 kb) | Adenovirus or Lentivirus [10] | Large packaging capacity of adenovirus (up to 36 kb) and lentivirus (~8 kb) accommodates larger genetic payloads [10] [11]. |

Tissue Tropism and Targeting Strategies

AAV Serotype Selection: Natural AAV serotypes display distinct tissue tropisms that can be leveraged for targeted delivery. For example, AAV2 demonstrates broad tropism, AAV8 and AAV9 show strong liver and muscle tropism, while AAV5 efficiently transduces photoreceptors and airway epithelial cells [12]. Engineered capsid variants are expanding these native tropisms to enable more precise targeting [13] [12].

Lentiviral Pseudotyping: The tropism of lentiviral vectors can be redirected through pseudotyping with envelope proteins from other viruses. The most common approach utilizes the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus G-protein (VSV-G), which confers broad tropism across many cell types [13]. Alternative envelopes from rabies virus, measles virus, or other families can redirect transduction to specific neuronal subsets or other specialized cell types.

Adenovirus Fiber Modifications: Natural adenovirus tropism is primarily determined by interactions between the viral fiber knob domain and cellular receptors (CAR, CD46). Genetic modification of the fiber protein enables retargeting to specific cell surface markers, enhancing specificity and reducing off-target transduction [10].

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Vector Engineering and Production Workflows

The production of high-quality viral vectors requires specialized methodologies that differ significantly between systems. Below is a standardized workflow for AAV production, one of the most complex manufacturing processes, highlighting key stages where lentiviral and adenoviral production would diverge.

Diagram 1: Viral vector production workflow highlighting key stages and plasmid requirements for different systems. AAV production requires a 3-plasmid system (red), while lentiviral production typically uses a 4-plasmid system (green).

Key Experimental Protocols

AAV Vector Production via Transient Transfection

Principle: The most common AAV production method uses HEK293 cells that are transfected with three plasmids: (1) the transgene plasmid containing ITRs, (2) the Rep/Cap plasmid providing replication and capsid proteins, and (3) the adenoviral helper plasmid providing essential helper functions [12].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Maintain HEK293 cells in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Seed cells at 70-80% confluence in cell factories or multilayer flasks for large-scale production.

- Plasmid Transfection: Use polyethylenimine (PEI) or calcium phosphate precipitation to co-transfect the three plasmids at an optimized ratio (typically 1:1:1 mass ratio) when cells reach 80-90% confluence.

- Harvest: Collect cells 48-72 hours post-transfection by scraping and centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 minutes.

- Lysis: Resuspend cell pellet in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) and perform three freeze-thaw cycles between -80°C and 37°C.

- Benzonase Treatment: Incubate lysate with benzonase (50 U/mL) at 37°C for 30 minutes to digest unpackaged nucleic acids.

- Purification: Purify vectors using iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation or affinity chromatography. For iodixanol gradients, centrifuge at 350,000 × g for 1 hour and collect the 40% iodixanol fraction containing viral particles.

- Concentration and Buffer Exchange: Use centrifugal concentrators for final concentration and exchange into formulation buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.001% Pluronic F-68).

- Quality Control: Determine vector genome titer by quantitative PCR, assess purity by SDS-PAGE, and test for adventitious agents.

Lentiviral Vector Transduction for Stable Cell Line Generation

Principle: Lentiviral vectors enable stable integration of transgenes through reverse transcription and integration into the host genome, making them ideal for creating stably modified cell lines [13].

Detailed Methodology:

- Vector Production: Produce lentiviral vectors by transfecting HEK293T cells with a 4-plasmid system (packaging, envelope, Rev, and transfer plasmids) using PEI transfection.

- Harvest and Concentration: Collect supernatant 48 and 72 hours post-transfection, filter through 0.45μm membrane, and concentrate by ultracentrifugation at 50,000 × g for 2 hours.

- Target Cell Preparation: Plate target cells at 30-50% confluence in growth medium supplemented with 8μg/mL polybrene to enhance transduction efficiency.

- Transduction: Add appropriate volume of lentiviral vector to achieve desired multiplicity of infection (MOI). Incubate for 24 hours.

- Selection and Expansion: Replace medium with selection antibiotic (e.g., puromycin, blasticidin) 48 hours post-transduction. Maintain selection pressure for 5-7 days until control cells are dead.

- Clonal Isolation: Isolate single cells by limiting dilution or FACS sorting into 96-well plates. Expand clones and screen for transgene expression.

- Validation: Validate stable integration by genomic PCR, Southern blot, or next-generation sequencing integration site analysis.

Adenoviral Vector Transduction for Transient High-Level Expression

Principle: Adenoviral vectors provide high transduction efficiency and rapid transgene expression, making them suitable for applications requiring high but transient protein production [10] [11].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Plating: Plate target cells at 70-80% confluence in appropriate growth medium 24 hours before transduction.

- Vector Thawing: Thaw adenoviral vector stock quickly at 37°C and place immediately on ice. Dilute in cold serum-free medium to desired concentration.

- Transduction: Remove growth medium from cells and add vector-containing medium. Incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours with gentle rocking every 15 minutes.

- Medium Replacement: Replace transduction medium with complete growth medium and return cells to incubator.

- Expression Monitoring: Monitor transgene expression beginning 6-24 hours post-transduction, with peak expression typically occurring at 24-48 hours.

- Functional Assays: Perform downstream functional assays during peak expression window (24-72 hours).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Vector Applications

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Packaging Plasmids | Provide essential viral genes in trans for vector production [12] | AAV Rep/Cap plasmids; LV Gag/Pol packaging plasmids [13] [12] |

| Helper Plasmids | Supply auxiliary viral functions needed for replication [12] | Adenoviral helper plasmids for AAV production [12] |

| Cell Lines | Specialized cells for vector production or transduction studies | HEK293/293T cells [12]; target cell lines (primary cells, stem cells) |

| Transfection Reagents | Facilitate plasmid DNA delivery into packaging cells | PEI, calcium phosphate, commercial lipid-based reagents [13] |

| Purification Matrices | Isolation and purification of viral vectors from crude lysates | Iodixanol gradients; affinity chromatography resins [13] |

| Titration Kits | Quantitative assessment of vector concentration | qPCR-based titer kits; physical particle detection assays |

| Transduction Enhancers | Improve vector uptake and gene transfer efficiency | Polybrene [13]; other cationic polymers |

| Tubulin inhibitor 33 | Tubulin inhibitor 33, MF:C24H22N4O3, MW:414.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-74 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-74, MF:C26H33N3O3, MW:435.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Manufacturing, Safety, and Regulatory Perspectives

Production Scale-Up and Cost Considerations

The transition from research-scale to clinical-grade vector manufacturing presents significant challenges that vary considerably between vector platforms. The table below compares key manufacturing considerations that impact development timelines, production costs, and commercialization potential.

Table 4: Manufacturing and Commercialization Comparison

| Manufacturing Aspect | AAV | Lentivirus | Adenovirus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production Complexity | High [10] | High [10] | Moderate [10] |

| Production Cost | High (raw materials account for 30-40% of cost) [10] | High [10] | Lower (50-60% less than AAV/LV) [10] |

| Scale-Up Challenges | Significant; requires strict control of cell culture conditions and purification parameters [10] | Significant; affected by cell density, transfection ratios, and requires high biosafety containment [10] | More straightforward; high replication enables large-scale production with standardized processes [10] |

| Common Impurities | Empty/partial capsids (significant productivity challenge) [13] | Replication-competent lentiviruses (RCL) [13] | Viral and host cell proteins, DNA [10] |

| Regulatory Precedents | Multiple approved products (e.g., Luxturna, Zolgensma) [13] [12] | Approved therapies (e.g., CAR-T products) [13] | Approved vaccines and oncolytic therapies [10] |

Safety Profiles and Risk Mitigation Strategies

AAV Vector Safety: AAV vectors present the most favorable safety profile with low immunogenicity and minimal risk of insertional mutagenesis due to predominantly episomal persistence [10] [13]. Primary safety concerns include dose-dependent immune responses, particularly at high systemic doses, and potential hepatotoxicity [12]. Preclinical studies include thorough biodistribution analysis and immune response characterization. Risk mitigation strategies include empty capsid removal, corticosteroid prophylaxis, and tissue-specific promoter use to limit off-target expression [12].

Lentiviral Vector Safety: While offering stable gene expression through genomic integration, lentiviral vectors present theoretical risks of insertional mutagenesis and oncogene activation [11] [13]. Modern self-inactivating (SIN) designs with deleted enhancer/promoter regions in the LTRs have significantly improved safety profiles [13]. Additional safety modifications include chromatin insulators to prevent transgene silencing and enhancer blocking. Regulatory requirements typically include integration site analysis in clinical trials to monitor for clonal dominance [10].

Adenoviral Vector Safety: The strong immunogenicity of adenoviral vectors represents both a therapeutic advantage (vaccines) and limitation (inflammatory toxicity) [10] [11]. First-generation vectors retaining viral genes elicit robust immune responses, while newer gutless designs with deleted viral coding sequences show improved safety profiles [10]. Preclinical evaluation includes thorough assessment of innate and adaptive immune responses, with dose escalation studies to establish therapeutic windows. Clinical monitoring focuses on inflammatory markers and organ function, particularly liver enzymes [10].

The selection of an optimal viral vector platform represents a critical decision point in gene therapy research and development, with significant implications for experimental success and therapeutic outcomes. AAV vectors excel in in vivo applications requiring long-term gene expression in non-dividing tissues with minimal immunogenicity, particularly for monogenic diseases affecting neurological, ocular, and muscular systems [10] [12]. Lentiviral vectors remain the gold standard for ex vivo cell engineering applications where stable genomic integration and persistent transgene expression through cell division are required, as evidenced by their success in CAR-T therapies and hematopoietic stem cell treatments [10] [13]. Adenoviral vectors provide unparalleled transduction efficiency and rapid, high-level transgene expression, making them ideal for vaccine development, oncolytic virotherapy, and applications requiring transient expression [10] [11].

Future directions in viral vector development focus on overcoming current limitations through capsid engineering to enhance tissue specificity and evade pre-existing immunity [13] [12], optimizing production processes to reduce costs and improve scalability [10] [13], and developing novel vector systems with enhanced safety profiles and larger cargo capacities. As the gene therapy field continues to evolve, the strategic selection and continued refinement of these viral vector platforms will remain essential for translating promising research into effective clinical therapies.

Gene therapy represents a paradigm shift in treating human diseases by addressing genetic defects at their root cause. The success of this intervention critically depends on the vectors that deliver therapeutic genetic material. While viral vectors have been the historical workhorse, accounting for 29 of the 35 approved vector-based therapies globally, non-viral vectors are gaining substantial momentum as safer, more scalable alternatives [1] [3]. These synthetic systems do not integrate into the host genome and typically elicit fewer immunogenic reactions than their viral counterparts [15]. Their broader cargo capacity and lower production costs make them particularly attractive for a wide range of therapeutic applications, from silencing disease-causing genes to encoding therapeutic proteins [3].

This guide focuses on three leading non-viral platforms: Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP), N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) conjugates, and physical methods employing novel nucleic acid formats like circular single-stranded DNA (CssDNA). Each platform possesses distinct characteristics, performance metrics, and optimal application contexts. We objectively compare their mechanisms, experimental outcomes, and practical implementation requirements to inform research and development decisions in the field of somatic cell gene therapy.

Performance Comparison of Major Non-Viral Platforms

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the three primary non-viral delivery platforms based on current research and approved therapeutics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Key Non-Viral Vector Platforms

| Feature | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) | GalNAc Conjugates | Physical Methods (e.g., CssDNA Electroporation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Pseudo-lipoprotein complex; ionizable lipid-mediated endosomal escape [16] | Covalent conjugate targeting the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) [16] | Electroporation to deliver DNA templates (e.g., CssDNA) into cells [17] |

| Typical Cargo | siRNA, mRNA, CRISPR components [15] [18] [3] | siRNA, ASO [18] [19] | Single-stranded DNA for gene insertion/correction [17] |

| Targeting Specificity | Predominantly liver (passive via ApoE/LDLR; active targeting possible) [16] | Highly specific to hepatocytes via ASGPR [19] [16] | Dependent on cell type being electroporated (ex vivo) [17] |

| Administration Route | Intravenous [16] | Subcutaneous [16] | Ex vivo delivery to cells [17] |

| Key Efficiency Metrics | ~1-4% endosomal escape efficiency [16]; >90% encapsulation efficiency [16] | <1 minute hepatocyte uptake post-SC injection [16]; High avidity (KD ≈ 5 nM) [16] | Up to 51% gene knock-in efficiency in HSPCs; 3-5x higher than linear ssDNA [17] |

| Approved Therapeutics | Patisiran (Onpattro) [1] [3], COVID-19 mRNA vaccines [18] | Givosiran (Givlaari), Lumasiran (Oxlumo), Inclisiran (Leqvio) [1] [3] | None approved to date (primarily in pre-clinical and research stage) [17] |

Platform Deep Dive: Mechanisms, Workflows, and Experimental Data

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP)

LNPs are multi-component systems typically composed of an ionizable lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and a PEGylated lipid [16]. The ionizable lipid is crucial for both encapsulating the nucleic acid cargo during formulation and for mediating endosomal escape after cellular uptake. The mechanism involves the ionizable lipid's protonation in the acidic environment of the endosome, which promotes a transition to a cone-shaped morphology. This change induces membrane curvature and fusion pore formation, facilitating the release of the genetic payload into the cytosol [16].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for LNP Formulation and Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102) | Core functional lipid that encapsulates nucleic acids and mediates endosomal escape [16]. |

| Helper Phospholipid (e.g., DSPC) | Provides structural integrity to the nanoparticle bilayer [16]. |

| Cholesterol | Enhances bilayer stability and fluidity, improving nanoparticle longevity [16]. |

| PEGylated Lipid | Shields the LNP surface, reduces aggregation, and modulates pharmacokinetics [16]. |

| Microfluidic Mixer | Essential equipment for controlled, reproducible LNP formation with high encapsulation efficiency [16]. |

Figure 1: LNP Delivery Mechanism. Following intravenous administration, LNPs are coated with ApoE, enabling uptake via LDL receptor-mediated endocytosis. In the acidic endosome, ionizable lipids protonate, facilitating endosomal escape and cytosolic release of the therapeutic cargo.

GalNAc Conjugates

GalNAc conjugates represent a minimalist approach by forgoing a complex particulate carrier. Instead, a tri-antennary N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) ligand is covalently conjugated directly to the therapeutic oligonucleotide (e.g., siRNA) [16]. This ligand has extremely high affinity for the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR), which is abundantly and almost exclusively expressed on the surface of hepatocytes [19] [16]. Upon binding, the conjugate is rapidly internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis. While a significant portion of the cargo may be degraded in lysosomes, the highly efficient and repetitive cycling of ASGPR to the cell surface ensures that a sufficient fraction of the siRNA escapes into the cytoplasm to achieve potent and durable gene silencing [16].

Experimental Protocol: Rational Design of GalNAc-Lipids for CRISPR Delivery A 2023 Nature Communications study detailed the structure-guided design of GalNAc-lipids for LDLR-independent hepatic delivery of CRISPR base editors [19]. The workflow is as follows:

- Ligand Design: Two trivalent GalNAc ligand scaffolds (TRIS-based "Design 1" and lysine-based "Design 2") were synthesized and covalently attached to different lipid anchors (e.g., DSG, Chol, C20) via PEG linkers of varying lengths [19].

- Formulation: GalNAc-lipids were mixed with other lipid excipients (ionizable lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, PEG-lipid) prior to LNP formation to ensure uniform surface display of the ligand. The LNPs were loaded with ABE8.8 mRNA and a guide RNA targeting Angptl3 or Pcsk9 [19].

- In Vivo Screening: Formulations were screened in Ldlr-/- mice to assess potency independent of the LDLR pathway. Doses ranged from 0.1 to 0.3 mg/kg [19].

- Optimization: The optimal formulation (GalNAc-Lipid "GL6" with a 36-unit PEG linker and a DSG lipid anchor at 0.05 mol%) was advanced into non-human primate (NHP) studies, including a novel LDLR-deficient NHP model [19].

- Outcome Measurement: Efficacy was measured via targeted amplicon sequencing of liver DNA to calculate editing percentages, and by ELISA to quantify target protein (ANGPTL3) reduction in blood [19].

Key Results: The optimized GalNAc-LNP (GL6) increased liver editing in LDLR-deficient NHPs from 5% (untargeted LNP) to 61%, with minimal off-target editing. In wild-type NHPs, a single dose led to a durable 89% reduction in blood ANGPTL3 protein six months post-dosing [19].

Physical Methods and Advanced Nucleic Acid Formats

Physical methods, such as electroporation, facilitate the direct delivery of nucleic acids into cells by creating transient pores in the cell membrane. The efficacy of this approach is now heavily influenced by the format of the genetic cargo. Recent advances highlight the superiority of circular single-stranded DNA (CssDNA) over traditional linear DNA templates for gene editing applications in primary cells [17].

Experimental Protocol: CssDNA for Gene Insertion in Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells (HSPCs) A 2025 Nature Communications study established a protocol for TALEN-mediated gene insertion in HSPCs using CssDNA [17]:

- Cell Culture: Human HSPCs are thawed and expanded for two days in cytokine-supplemented media [17].

- Nuclease Delivery: On day 2, cells are electroporated with mRNA encoding TALENs and helper proteins (HDR-Enh01, Via-Enh01) [17].

- Template Delivery: On day 3, cells undergo a second electroporation with the CssDNA donor template (0.6 kb to 2.2 kb in length, flanked by ~300 bp homology arms) [17].

- Analysis: Cells are analyzed on day 4 (or later) for gene knock-in efficiency (via flow cytometry for a reporter gene), cell viability, and differentiation potential (via colony-forming unit assays). Engraftment capacity is tested by transplanting edited HSPCs into immunodeficient NCG mice [17].

Key Results: The CssDNA editing process achieved over 40% gene knock-in efficiency in HSPCs, a 3- to 5-fold increase compared to linear ssDNA (LssDNA). This correlated with a higher knock-in/knock-out ratio, indicating more precise integration. Critically, CssDNA-edited HSPCs showed a higher propensity to engraft and maintain gene edits in murine models compared to AAV-edited cells, attributed to a more primitive, quiescent metabolic state [17].

Figure 2: CssDNA Workflow for HSPC Editing. The process involves sequential electroporation of nuclease mRNA and CssDNA donor template into expanded HSPCs, followed by in vitro and in vivo functional analysis.

The choice between LNP, GalNAc conjugates, and physical methods like CssDNA electroporation is dictated by the therapeutic application. LNPs offer versatility in cargo type and are the platform of choice for mRNA delivery and vaccines. GalNAc conjugates provide an elegant, highly targeted solution for liver-specific siRNA delivery, enabling subcutaneous, long-acting dosing regimens. CssDNA-based physical methods present a powerful and potentially safer alternative to AAV for ex vivo gene editing, particularly in sensitive primary cells like HSPCs, where high knock-in efficiency and preservation of cell fitness are paramount.

The ongoing refinement of these platforms—through the design of novel ionizable lipids, optimized targeting ligands, and improved nucleic acid formats—will continue to expand the reach of non-viral gene therapy, potentially moving it beyond rare diseases to address more common conditions.

In the field of gene therapy, the selection of an appropriate gene delivery vector is a fundamental determinant of therapeutic success. Vectors are engineered systems designed to transport genetic cargo into target cells and must overcome multiple biological barriers to achieve effective transduction—the process of delivering and expressing a transgene. The core properties defining any vector's utility are its transduction efficiency (the proportion of cells that successfully express the transgene), cargo capacity (the size of the genetic material it can carry), and tropism (its specificity for particular cell types) [20] [21]. These properties directly impact the safety, efficacy, and practical application of gene therapies for both research and clinical use.

Vectors are broadly categorized into viral and non-viral systems. Viral vectors leverage the natural ability of viruses to infect cells, while non-viral vectors use synthetic or physical methods for gene delivery [20] [22]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these platforms, focusing on their key biological properties, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their experimental and therapeutic designs.

Comparative Analysis of Vector Properties

The table below summarizes the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of major viral and non-viral vector systems, providing a clear comparison of their performance across key parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Viral and Non-Viral Vector Systems

| Vector Type | Transduction Efficiency | Cargo Capacity | Primary Tropism & Targeting Mechanism | Gene Expression Duration | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | High in vivo [1] | ~4.7 kb [23] [24] | Broad; naturally occurring and engineered serotypes target muscle, liver, CNS, retina [1] [23] | Long-term, but transient in dividing cells (non-integrating) [25] | Favorable safety profile, low immunogenicity [1] [25] | Limited cargo size, potential for pre-existing immunity [26] [22] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | High ex vivo and in vivo [1] | ~8 kb [21] | Broad; can transduce dividing and non-dividing cells; pseudotyping with VSV-G expands tropism [21] [24] | Long-term (integrating) [25] [24] | Stable genomic integration, suitable for ex vivo cell therapy (e.g., CAR-T) [21] [24] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis, though reduced with SIN designs [26] [24] |

| Adenovirus (AdV) | High [1] | Up to ~36 kb [27] [24] | Very broad; naturally tropic for respiratory epithelial cells [1] | Transient (non-integrating) [20] [27] | Very large cargo capacity, high titer production [27] [22] | Strong immune response, high immunogenicity [20] [21] |

| Gamma-Retrovirus (γRV) | High for dividing cells [21] | ~10 kb [26] [24] | Restricted to dividing cells [21] [25] | Long-term (integrating) [25] | Long-term gene expression [25] | Only transduces dividing cells; higher risk of insertional mutagenesis [26] [24] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Lower than viral vectors in vivo; improving [20] [22] | High (theoretically unlimited) [22] | Primarily hepatic after systemic administration; targetability is an area of active research [1] [22] | Transient [22] | Large cargo capacity, good safety profile, scalable manufacturing [27] [22] | Lower transfection efficiency, potential toxicity at high doses, often requires repeated administration [20] [22] |

| Cationic Polymers (e.g., PEI) | Variable; generally lower than viral vectors [25] | High [25] | Low innate specificity; can be modified with targeting ligands [25] | Transient [27] | Biodegradable versions available, high cation charge density for nucleic acid compaction [27] [25] | Can be cytotoxic (e.g., non-biodegradable PEI), low specificity and transfection efficiency in vivo [25] |

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Quantifying Transduction Efficiency

Transduction efficiency is typically measured as the percentage of cells that successfully express the transgene post-delivery. In clinical manufacturing, this is a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA). For example, in CAR-T cell production, lentiviral transduction efficiencies typically range between 30–70%, as assessed by flow cytometry for surface marker detection or quantitative PCR for Vector Copy Number (VCN) analysis [21].

Key process parameters that critically influence transduction efficiency include:

- Cell Quality and Activation State: Pre-activating T cells upregulates viral receptor expression, significantly enhancing transduction [21].

- Multiplicity of Infection (MOI): This ratio of viral particles to target cells must be carefully titrated. A higher MOI can increase efficiency but also raises the risk of cellular toxicity and higher VCN [21].

- Transduction Enhancers: Additives such as polycations (e.g., protamine sulfate) and the use of physical methods like spinoculation (centrifugation of vector onto cells) enhance cell-vector contact and improve efficiency [21].

- Vector Engineering: Pseudotyping lentiviral vectors with the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus G-glycoprotein (VSV-G) confers broad tropism and improves stability, enhancing transduction across diverse immune cell types [21].

Assessing Cargo Capacity and Its Impact

Cargo capacity directly dictates the therapeutic genes a vector can deliver. The inherent limitations of each platform can be overcome through engineering:

- Adenoviruses offer the largest native capacity, with high-capacity "gutless" vectors accommodating up to ~36 kb of foreign DNA, enabling the delivery of large genetic sequences like the dystrophin gene for Duchenne muscular dystrophy [20] [27].

- AAV's limited ~4.7 kb capacity is a significant constraint. To overcome this, researchers use dual-AAV approaches, splitting a large transgene into two halves that recombine inside the target cell. This strategy has been successfully applied in a first-in-human therapy for hereditary hearing loss [1].

- Non-viral vectors like LNPs and polymers have a high and flexible cargo capacity, easily accommodating large CRISPR-Cas9 systems or multiple genetic elements [22].

Engineering and Measuring Tropism

Tropism defines a vector's specificity for a particular cell or tissue type. It is a critical factor for maximizing on-target delivery and minimizing off-target effects and toxicity [23]. Both viral and non-viral platforms are actively engineered to achieve precise targeting.

Diagram 1: Strategies for Engineering Viral Vector Tropism

For non-viral vectors, tropism is achieved through functionalization. This involves conjugating targeting ligands—such as antibodies, peptides, or aptamers—to the surface of nanoparticles or polymeric carriers. These ligands bind to receptors overexpressed on specific target cells, enabling receptor-mediated uptake [22]. For instance, folate-conjugated liposomes are designed to target cancer cells with high folate receptor expression [22].

Experimental validation of successful targeting involves:

- In vitro binding assays using cell lines expressing the target receptor.

- Biodistribution studies in animal models, quantifying vector genomes in different tissues after administration.

- Histological analysis of tissues to confirm transgene expression in the target cell type.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimizing Lentiviral Transduction of T Cells for CAR-T Therapy

This protocol outlines the critical steps for achieving high-efficiency transduction of human T cells, a cornerstone of CAR-T cell therapy manufacturing [21].

1. T Cell Activation:

- Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a leukapheresis product.

- Activate T cells using anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (e.g., Dynabeads) in a serum-free medium.

- Culture for 24-48 hours before transduction. Critical Parameter: Cell activation state directly correlates with transduction efficiency.

2. Vector Preparation and Transduction:

- Thaw a high-titer lentiviral vector (e.g., VSV-G pseudotyped) on ice.

- Calculate the required vector volume based on the Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) and cell count. An MOI between 5 and 20 is typical, but requires empirical optimization.

- Add the vector to the cells. Include transduction enhancers such as protamine sulfate (4-8 µg/mL) or Vectofusin-1 to the culture medium.

- Use Spinoculation: Centrifuge the cell-vector mixture at 800-2000 x g for 30-120 minutes at 32°C. This significantly enhances cell-vector contact and efficiency.

3. Post-Transduction Culture and Analysis:

- After 24 hours, remove the vector-containing medium and replace with fresh medium supplemented with cytokines (e.g., IL-2 at 50-100 IU/mL).

- Expand cells for 7-14 days.

- Analyze Transduction Efficiency: At day 3-5, analyze by flow cytometry for CAR or reporter gene expression.

- Measure Vector Copy Number (VCN): Use droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) on genomic DNA to ensure VCN remains below 5 copies per cell for clinical safety [21].

Protocol: Formulating and Testing Ligand-Targeted Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

This protocol describes the creation of targeted LNPs for cell-specific gene delivery [22].

1. Lipid Mixture Preparation:

- Prepare a lipid mixture in ethanol. A standard formulation includes:

- Ionizable cationic lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA): For nucleic acid complexation and endosomal escape.

- Phospholipid (e.g., DSPC): Provides structural integrity.

- Cholesterol: Stabilizes the LNP bilayer.

- PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG2000): Reduces nonspecific uptake and improves stability.

- For targeting, replace a portion of the DMG-PEG2000 with a PEG-lipid conjugate bearing a targeting ligand (e.g., an antibody, peptide, or aptamer).

2. LNP Formation via Microfluidics:

- Mix the ethanolic lipid stream with an aqueous stream containing the mRNA or DNA payload at a specific flow rate ratio in a microfluidic device.

- This process results in the spontaneous formation of LNPs encapsulating the genetic material.

- Dialyze or use tangential flow filtration (TFF) to remove ethanol and exchange the buffer.

3. In Vitro Validation of Targeting:

- Incute the formulated LNPs with two cell types: one expressing the target receptor and a control cell line lacking the receptor.

- After incubation, measure transfection efficiency by quantifying reporter protein expression (e.g., GFP via flow cytometry or luciferase activity).

- To confirm receptor-specific uptake, perform a competition assay by pre-incubating the target cells with an excess of free ligand, which should block LNP binding and reduce transfection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Vector Research and Development

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| VSV-G Envelope Plasmid | Pseudotyping enveloped viral vectors (LV, γRV) to confer broad tropism and enhance vector stability [21]. | Production of lentiviral vectors with high titer and ability to transduce a wide range of cell types. |

| Transduction Enhancers (e.g., Protamine Sulfate, Vectofusin-1) | Polycations that reduce electrostatic repulsion between viral particles and cell membranes, increasing transduction efficiency [21]. | Added during ex vivo transduction of T cells or hematopoietic stem cells to improve gene transfer rates. |

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA) | A component of LNPs that binds nucleic acids at low pH and promotes endosomal escape following cellular uptake [22]. | Formulating LNPs for siRNA (Onpattro) or mRNA delivery; critical for efficient cytosolic delivery. |

| Cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IL-7, IL-15) | Support the survival, expansion, and function of immune cells during and after ex vivo transduction [21]. | Culture medium supplement for manufacturing CAR-T cells and NK cells to maintain viability and potency. |

| Anti-CD3/CD28 Antibodies | Synthetic activation signals for T cells, mimicking antigen presentation and initiating cell proliferation [21]. | In vitro activation of primary T cells prior to viral transduction, a critical step for high efficiency. |

| Aurein 3.2 | Aurein 3.2, MF:C82H138N22O21, MW:1768.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FGFR1 inhibitor-9 | FGFR1 inhibitor-9, MF:C27H20ClNO5, MW:473.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between viral and non-viral vectors is a fundamental strategic decision in gene therapy research and development. As the data demonstrates, viral vectors (AAV, LV, AdV) currently offer superior transduction efficiency and have enabled multiple approved therapies, but they are constrained by immunogenicity, cargo limits, and complex manufacturing [20] [1] [25]. In contrast, non-viral vectors (LNPs, polymers) provide advantages in safety, cargo flexibility, and scalability, though they are still catching up in delivery efficiency and targeting specificity [27] [22].

The future of the field lies in the continued engineering of both platforms to overcome their limitations. For viral vectors, this involves sophisticated capsid and envelope engineering to de-target innate immunity and re-target desired tissues [23]. For non-viral vectors, the focus is on developing novel materials and conjugation strategies to enhance stability, promote endosomal escape, and achieve precise cell-specific targeting [22]. The ongoing convergence of these platforms—such as using viral components to enhance non-viral systems—promises to yield a new generation of versatile, safe, and highly effective vectors for gene therapy.

Gene therapy represents a transformative approach in modern medicine, enabling the treatment of diseases at their genetic root cause. The clinical success of these therapies is fundamentally dependent on the vectors used to deliver therapeutic genetic material into target cells. These vectors are broadly classified into viral and non-viral systems, each with distinct biological properties, clinical applications, and regulatory profiles [1]. Viral vectors, engineered from modified viruses, leverage natural infection mechanisms for high-efficiency delivery. In contrast, non-viral vectors use synthetic or biological compounds, such as lipids or polymers, to ferry genetic cargo with a typically improved safety profile [25]. As of mid-2025, the global regulatory landscape has seen the approval of at least 35 vector-based gene therapies, with 29 being viral-based and 6 utilizing non-viral methods [1] [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approved therapies, detailing their performance, supported by experimental data and methodologies, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The gene therapy market has witnessed accelerated growth, with 2024 being a landmark year featuring several "first" approvals, including the first T-cell receptor (TCR) therapy and the first mesenchymal stem cell product in the U.S. [28]. The table below summarizes the quantitative approval landscape for vector-based gene therapies.

Table 1: Global Approval Summary for Vector-Based Gene Therapies (as of 2025)

| Vector Category | Number of Approved Therapies | Key Examples (Indication) |

|---|---|---|

| Viral-Based Total | 29 [1] | Kymriah (Leukemia) [1], Zolgensma (SMA) [29], Luxturna (Retinal Dystrophy) [1] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | 14 (ex vivo) [1] | Zynteglo (Beta Thalassemia) [1], Skysona (Cerebral Adrenoleukodystrophy) [1] |

| Adenovirus (Ad) | 4 [1] | Gendicine (Head and Neck Cancer) [1], Adstiladrin (Bladder Cancer) [1] |

| Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) | 9 [1] | Hemgenix (Hemophilia B) [1], Elevidys (DMD) [1], Roctavian (Hemophilia A) [1] |

| Non-Viral-Based Total | 6 [1] | Onpattro (hATTR Amyloidosis) [1], Givlaari (Acute Hepatic Porphyria) [1] |

| Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) | 1 [1] | Onpattro (siRNA for hATTR) [1] [3] |

| GalNAc Conjugation | 5 [1] | Leqvio (Hypercholesterolemia) [1], Oxlumo (Primary Hyperoxaluria) [1] |

The distribution of approved products underscores the historical dominance of viral vectors, particularly in ex vivo cell engineering and in vivo treatments for monogenic diseases. However, the recent rise of non-viral platforms, especially GalNAc-conjugated therapies for liver-targeted delivery, highlights a significant shift towards scalable and less immunogenic delivery solutions [3].

Approved Viral Vector Therapies: In-Depth Analysis

Viral vectors are the cornerstone of approved gene therapies, prized for their high transduction efficiency and ability to achieve long-term gene expression [25]. The choice of viral vector is dictated by the therapeutic goal, target cell type, and required duration of expression.

Table 2: Key Approved Viral Vector Therapies and Clinical Evidence

| Product (Vector) | Therapeutic Indication | Key Clinical Trial Efficacy Data | Administration Route & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kymriah (LV) [1] | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | Pivotal trial (ELIANA): 83% overall remission rate in r/r pediatric patients [1]. | Ex vivo transduction of patient T-cells ensures targeted delivery to cancerous B-cells, minimizing systemic exposure. |

| Zolgensma (AAV9) [29] | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | Phase 3 STR1VE trial: 100% event-free survival at 14 months; 92% achieving motor milestones unseen in natural history [29]. | Intravenous (IV) systemic delivery. AAV9 serotype has high tropism for motor neurons, crossing the blood-brain barrier. |

| Luxturna (AAV2) [1] | RPE65-mediated Retinal Dystrophy | Phase 3: Significant improvement in multi-luminance mobility test; 93% of participants showed improved functional vision [1]. | Subretinal injection. Localized delivery ensures high vector concentration at the target retinal pigment epithelium cells. |

| Itvisma (AAV9) [30] | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) in patients ≥2 years | Phase 3 STEER study: Statistically significant improvement in motor function (HFMSE score) sustained over 52 weeks [30]. | Intrathecal injection. Direct delivery to cerebrospinal fluid allows lower vector dose and targets spinal cord motor neurons. |

Experimental Protocols for Viral Therapies

The development and validation of these therapies rely on standardized preclinical and clinical protocols.

Ex Vivo Lentiviral Protocol (e.g., CAR-T Production): Patient T-cells are harvested via leukapheresis and activated ex vivo using anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads. These activated T-cells are then transduced with a recombinant lentiviral vector encoding the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) in the presence of polycations like polybrene to enhance transduction efficiency. The transduced cells are expanded in culture using recombinant human cytokines (e.g., IL-2) for 7-10 days before being infused back into the patient [1] [24].

In Vivo AAV Protocol (e.g., ITVSMA Clinical Trial): The Phase III STEER study for Itvisma was a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Patients with confirmed SMN1 mutations received a single intrathecal bolus injection of the AAV9-based therapy. The primary efficacy endpoint was the change from baseline in the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale-Expanded (HFMSE) score at 52 weeks. Safety was assessed by monitoring for adverse events of special interest, including hepatotoxicity and cardiotoxicity, consistent with the known risks of AAV therapies [30].

Approved Non-Viral Vector Therapies: In-Depth Analysis

Non-viral vectors offer advantages in safety, manufacturing scalability, and reduced immunogenicity. Their approved applications are pioneering targeted delivery, particularly to the liver.

Table 3: Key Approved Non-Viral Vector Therapies and Clinical Evidence

| Product (Platform) | Therapeutic Indication | Key Clinical Trial Efficacy Data | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onpattro (LNP) [1] [3] | Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR) | APOLLO Phase 3: Significantly reduced modified Neuropathy Impairment Score +7 points vs. placebo. | Delivers siRNA to hepatocytes, mediating degradation of mutant and wild-type TTR mRNA. |

| Givlaari (GalNAc) [1] | Acute Hepatic Porphyria (AHP) | Phase 3 ENVISION: Reduced porphyria attacks by 74% compared to placebo. | GalNAc ligand targets asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) on hepatocytes. Delivers siRNA against aminolevulinic acid synthase 1 (ALAS1). |

| Leqvio (GalNAc) [1] | Hypercholesterolemia | Phase 3 ORION-9,10,11: Sustained reduction of LDL cholesterol by ~50% with biannual dosing. | GalNAc-conjugated siRNA targets and silences PCSK9 mRNA in hepatocytes. |

| Rivfloza (GalNAc) [1] | Primary Hyperoxaluria | Phase 3: Achieved substantial reduction in urinary oxalate levels. | GalNAc-conjugated siRNA against hydroxyacid oxidase 1 (HAO1) gene, reducing oxalate production. |

Experimental Protocols for Non-Viral Therapies

The clinical validation of non-viral therapies involves unique considerations for biodistribution and silencing efficacy.

LNP-siRNA Protocol (e.g., Onpattro Clinical Trial): The APOLLO trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 study. Patients received 0.3 mg/kg of patisiran via intravenous (IV) infusion every three weeks. Co-administration of corticosteroids, acetaminophen, and H1/H2 blockers was required to preempt infusion-related reactions. The primary endpoint was the change from baseline in the mNIS+7 score at 18 months. Efficacy was corroborated by measuring serum TTR protein levels as a pharmacodynamic biomarker [1] [3].

GalNAc-siRNA Protocol (e.g., Givlaari Clinical Trial): The ENVISION trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 study. Patients received subcutaneous injections of givosiran at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg monthly. The primary efficacy endpoint was the annualized rate of composite porphyria attacks. The delivery platform's success was evidenced by measuring urinary aminolevulinic acid levels, confirming target engagement in the heme biosynthesis pathway [1].

Comparative Analysis: Performance Data of Viral vs. Non-Viral Vectors

The choice between viral and non-viral vectors involves a careful trade-off between efficacy, safety, and manufacturability.

Diagram Title: Vector selection is a multi-parameter decision tree.

Table 4: Direct Comparison of Viral vs. Non-Viral Vector Properties

| Parameter | Viral Vectors (AAV, LV) | Non-Viral Vectors (LNP, GalNAc) |

|---|---|---|

| Transduction/Efficiency | High. Natural infection mechanism; sustained expression [25]. | Variable, often lower. Must overcome endosomal degradation; typically transient effect [25]. |

| Cargo Capacity | Limited. AAV: ~4.7kb [3]. LV: ~8kb [24]. | Large. Can deliver large DNA, mRNA, CRISPR ribonucleoproteins [25]. |

| Immunogenicity | Moderate to High. Can trigger innate/adaptive immunity, limiting re-dosing [25] [3]. | Low. Safer profile, but LNPs can cause infusion reactions [25] [3]. |

| Genotoxicity Risk | Yes. LV/RV integrate into host genome, risk of insertional mutagenesis [24] [3]. | Very Low. Primarily episomal; no known risk of insertional mutagenesis [25]. |

| Manufacturing & Scalability | Complex and costly. Requires production in mammalian cell lines [25]. | Simpler and more scalable. Based on synthetic chemistry, good for GMP [25]. |

| Typical Dosing | Often one-time (e.g., Zolgensma, Luxturna) [1] [29]. | Often multiple doses (e.g., Leqvio is biannual) [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Advancing gene therapy research requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details essential tools for developing and evaluating vector systems.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Vector Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polycations (e.g., Polybrene) | Enhance viral vector infection efficiency by neutralizing charge repulsion between vector and cell membrane [24]. | Used during ex vivo transduction of T-cells with lentiviral vectors to improve CAR transfer efficiency [24]. |

| LNP Formulation Lipids | Cationic/ionizable lipids bind nucleic acids; PEG-lipids stabilize particles; helper lipids support bilayer structure [25]. | Formulate siRNA (as in Onpattro) or mRNA into nanoparticles for in vivo delivery [1] [25]. |

| Cytokines (e.g., IL-2) | T-cell growth factor that promotes the expansion and survival of genetically modified T-cells during ex vivo culture [24]. | Critical for expanding CAR-T cells to sufficient numbers for therapeutic infusion after transduction [24]. |

| AAV Serotype Libraries | Different AAV serotypes (e.g., AAV2, AAV8, AAV9) exhibit distinct tropisms for various tissues (e.g., liver, CNS, muscle) [25] [3]. | Screening to identify the optimal serotype for a specific target tissue in preclinical models [3]. |

| GalNAc Ligand | A carbohydrate ligand that binds with high affinity to the ASGPR, which is highly expressed on hepatocytes [1] [3]. | Conjugated to siRNA or ASO therapeutics to achieve targeted delivery to the liver [1]. |

| Selective Promoters/Enhancers | Regulatory DNA sequences that restrict transgene expression to specific cell or tissue types (e.g., synapsin promoter for neurons) [3]. | Incorporated into viral vectors (AAV, LV) to limit off-target expression and enhance safety [3]. |

| PAN endonuclease-IN-2 | PAN endonuclease-IN-2|Influenza Antiviral Research Compound | PAN endonuclease-IN-2 is a potent research compound that inhibits influenza virus replication. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Cyclo(Gly-Arg-Gly-Glu-Ser-Pro) | Cyclo(Gly-Arg-Gly-Glu-Ser-Pro), MF:C23H37N9O9, MW:583.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram Title: LNP and viral vectors have distinct production workflows.

The current market landscape demonstrates a dynamic and maturing gene therapy sector. Viral vectors, particularly AAV and LV, have established a stronghold for indications requiring high-efficiency, durable gene expression, as evidenced by landmark therapies for SMA, retinal diseases, and blood cancers. Meanwhile, non-viral vectors, led by LNPs and GalNAc platforms, are carving out a critical niche by offering a safer, more scalable, and commercially viable path forward, especially for liver-targeted diseases and applications requiring redosability. The future of gene delivery lies not in a single dominant platform, but in the continued innovation and refinement of both viral and non-viral systems. Emerging strategies like capsid engineering, dual-vector systems to overcome cargo limits, and advanced non-viral designs for extrahepatic delivery will collectively expand the reach of gene therapies to a broader spectrum of human diseases [1] [3].

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation of Vector Platforms

Lentiviral vectors (LVs) have emerged as a premier delivery platform for ex vivo gene therapy, enabling the genetic modification of a patient's own cells outside the body before reinfusion. Derived from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), LVs are distinguished by their ability to transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells and provide stable genomic integration and long-term transgene expression [24] [31]. These properties make LVs particularly suitable for engineering hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and T lymphocytes, the cornerstone of advanced therapies for genetic disorders and cancers [24] [31] [32]. This guide objectively compares LV performance in two dominant applications: CAR-T cell therapies for hematological malignancies and HSC-based therapies for inherited monogenic diseases, providing researchers with a direct comparison of experimental data, protocols, and safety considerations.

Comparative Analysis of LV Performance in CAR-T vs. HSC Therapies

The performance of LV systems differs significantly between therapeutic applications due to distinct biological targets and clinical requirements. The table below summarizes key performance metrics and their direct impact on therapeutic outcomes.

| Performance Metric | LV in CAR-T Cell Therapy | LV in HSC-Based Therapy | Impact on Therapeutic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Transduction Efficiency | 30-70% [31] | Varies; can be optimized via pre-stimulation & enhancers [31] | Directly influences the dose of therapeutic cells; critical for product potency. |

| Vector Copy Number (VCN) Safety Window | Generally maintained below 5 copies/cell [31] | Carefully monitored; clonal expansions reported (e.g., in HMGA2) [33] | High VCN raises genotoxicity risk; must balance with sufficient transgene expression. |

| Key Challenge | Functional persistence of CAR-T cells; tonic signaling [34] | Ensuring engraftment and long-term polyclonal reconstitution [35] [33] | CAR-T: Impacts durability of anti-tumor response.HSC: Affects cure longevity and safety profile. |

| Primary Safety Concern | Secondary malignancies (rare reports) [33] | Insertional mutagenesis leading to clonal dominance or malignancy [33] | Drives requirement for extensive integration site analysis and long-term patient follow-up. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Ex Vivo Manufacturing of LV-Modified CAR-T Cells

The production of CAR-T cells is a multi-step process where critical process parameters (CPPs) must be tightly controlled to ensure the critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the final product [31].

- Leukapheresis and T-Cell Isolation: T cells are collected from the patient via leukapheresis and isolated from other blood components [31].

- T-Cell Activation: Isolated T cells are activated using methods such as CD3/CD28 stimulation, a critical step that upregulates receptors for viral entry and primes cells for transduction [31].

- Lentiviral Transduction:

- The activated T cells are exposed to the LV carrying the CAR transgene.

- Multiplicity of infection (MOI), which defines the ratio of functional vector particles to target cells, is carefully titrated to balance high transduction efficiency against cell toxicity and excessive VCN [31]. MOI is a key CPP.

- Spinoculation (centrifugation during transduction) is often employed to enhance cell-vector contact and improve efficiency [31].