Advancing Andrology: A Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning Frameworks for Male Infertility Prediction

Male factors contribute to approximately 30-50% of infertility cases, yet diagnosis often relies on subjective traditional methods.

Advancing Andrology: A Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning Frameworks for Male Infertility Prediction

Abstract

Male factors contribute to approximately 30-50% of infertility cases, yet diagnosis often relies on subjective traditional methods. This article synthesizes current research on machine learning (ML) frameworks for male infertility prediction, addressing a critical need for objective, accurate diagnostic tools. We explore foundational concepts of male infertility etiology and data requirements, detail diverse ML methodologies from standard classifiers to advanced hybrid models, analyze optimization strategies for handling real-world data challenges like class imbalance, and critically evaluate model validation and performance comparison. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive technical foundation, highlighting how ML enhances diagnostic precision, reveals novel biomarkers, and enables non-invasive screening, ultimately supporting the development of personalized therapeutic strategies and improved clinical decision-support systems.

Understanding Male Infertility and the Data Landscape for Machine Learning

Male infertility represents a significant yet often underestimated global health challenge, implicated in approximately 50% of all infertility cases among couples [1]. The diagnosis of male factor infertility exerts a profound physical and emotional impact on affected individuals and couples, affecting overall quality of life [1]. Despite its prevalence, the true burden of male infertility remains difficult to quantify due to substantial gaps in epidemiological data, regional disparities in reporting, and significant limitations in diagnostic methodologies [1]. This application note examines the global burden of male infertility through the analytical lens of machine learning (ML) frameworks, which offer promising avenues for addressing critical diagnostic limitations. We present structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols for biomarker validation, visual workflows for diagnostic pathways, and essential research reagent solutions to advance ML-driven research in male reproductive health.

Global Prevalence and Epidemiological Data

The precise prevalence of male infertility remains elusive, as current estimates primarily derive from couples actively seeking treatment, potentially underestimating the problem in the general population [1]. Infertility, broadly defined as the inability to achieve pregnancy after one year of unprotected intercourse, affects approximately 15% of all couples globally [1]. Epidemiological data reveal complex patterns and significant knowledge gaps, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Global Epidemiological Data on Male Infertility

| Metric | Regional Variation | Data Source | Limitations/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Prevalence | Affects ~15% of couples globally; male factor contributes to ~50% of cases [1] | Multiple survey data | Based mainly on couples seeking treatment; likely underestimates true prevalence [1] |

| Service Utilization | 7.5% of sexually active men (15-44 years) sought fertility help (2002 data) [1] | National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) | Translates to 3.3-4.7 million men with lifetime visits; 787,000-1.5 million with visits in preceding year [1] |

| Klinefelter Syndrome (KS) | Global ASPR: 11-12/100,000 (1990-2021) [2] | Global Burden of Disease Study | Highest rates in Western/Eastern Europe (19-20/100,000); fastest growth in East Asia (AAPC=0.44) [2] |

| Surgical Procedure Rates | Highest in men 25-34 (126/100,000); men 35-44 (83/100,000) [1] | National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery (2006) | Data excludes specialized reproductive clinics; details often lacking [1] |

| Evaluation Gaps | 17.7-27.4% of male partners in couples seeking infertility care undergo no evaluation [1] | NSFG (1995, 2002, 2006-2008 cycles) | Demographic and economic factors affect whether men seek treatment [1] |

Critical analysis of data sources reveals systematic limitations. The National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), while nationally representative, contains small sample sizes for men reporting reproductive health service utilization [1]. The National ART Surveillance System (NASS) initially lacked detailed male partner information, though recent improvements now capture male age and infertility etiology [1]. Validation studies indicate that ICD-9 codes for male infertility demonstrate high specificity (92.3-99.7%) but uncertain sensitivity in claims data analysis [1]. The emerging Andrology Research Consortium (ARC) database reports that only 9.8% of couples undergoing IUI and 28% undergoing IVF reported prior male factor evaluation, highlighting significant diagnostic gaps [1].

Current Diagnostic Gaps and Biomarker Potentials

Traditional semen analysis, assessing parameters like concentration, motility, and morphology, faces criticism for insufficient reliability in predicting fertility outcomes [3]. This has stimulated research into molecular biomarkers across various "Omics" domains to identify more accurate diagnostic and prognostic indicators [4]. Systematic reviews identify several promising biomarkers with robust predictive capacity for male infertility, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Promising Molecular Biomarkers for Male Infertility Diagnosis

| Biomarker Category | Specific Biomarker | Predictive Performance (AUC Median) | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm DNA Integrity | Sperm DNA damage [4] | 0.67 | Direct evaluation of genetic material integrity; predicts ART outcomes [4] |

| Chromatin Modification | γH2AX levels [4] | 0.93 | Strand break-associated chromatin modifications; excellent diagnostic value [4] |

| Transcriptomics | miR-34c-5p in semen [4] | 0.78 | Well-characterized noncoding RNA; robust transcriptomic biomarker [4] |

| Proteomics | TEX101 in seminal plasma [4] | 0.69 | Protein with excellent diagnostic potential for sperm quality and fertilizing capacity [4] |

| Metabolomics | Metabolomic profiles [4] | Good predictive value | Comprehensive metabolic snapshot; superior to individual metabolites for inferring sperm quality [4] |

Metabolomics emerges as a particularly promising approach, studying products of cellular metabolic activities including amino acids, hormones, carbohydrates, nucleotides, and lipids [3]. Research links male infertility to increased oxidative stress from excessive reactive oxidants in seminal plasma and impaired antioxidant defense mechanisms [3]. Studies reveal altered levels of citrate, lactate, and glycerylphosphorylcholine in seminal plasma of men with azoospermia, suggesting metabolic pathway disruptions [3].

Standardized phenotypic classification remains another critical gap. The International Male Infertility Genomics Consortium has substantially revised the "HPO tree" based on clinical work-ups of infertile men, providing a standardized vocabulary containing 49 HPO terms linked in a logical hierarchy [5]. This facilitates systematic phenotype recording and communication between geneticists and andrologists, promoting discovery of novel genetic causes for non-syndromic male infertility [5].

Machine Learning Framework Integration

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are increasingly integrated into reproductive medicine to address diagnostic challenges. Global surveys among IVF specialists and embryologists demonstrate a substantial increase in AI adoption, rising from 24.8% in 2022 to 53.22% in 2025 (including both regular and occasional use) [6]. Embryo selection remains the dominant application, with strong interest in sperm selection (87.5% in 2022) [6].

Machine learning-based analysis of sperm videos represents a significant advancement for male infertility investigation. Studies utilizing classical and modern ML techniques, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), demonstrate that automated sperm motility prediction is rapid to perform and consistent [7]. Interestingly, algorithm performance decreased when participant data was added to the video analysis, suggesting the primacy of visual motility characteristics in ML prediction models [7].

AI tools are advancing in sophistication. The iDAScore correlates significantly with cell numbers and fragmentation in cleavage-stage embryos and shows predictive value for live birth outcomes [6]. The BELA system, a fully automated AI tool, predicts embryo ploidy using time-lapse imaging and maternal age, demonstrating higher accuracy than its predecessor (STORK-A) and offering a non-invasive alternative to preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) [6].

Despite this progress, barriers to AI adoption persist, including cost (38.01% of respondents) and lack of training (33.92%) [6]. Ethical concerns and over-reliance on technology were cited as significant risks by 59.06% of 2025 survey respondents [6]. Nevertheless, future investment interest remains strong, with 83.62% of 2025 respondents likely to invest in AI within 1-5 years [6].

Diagnostic Pathway with ML Integration

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive diagnostic workflow for male infertility that integrates traditional assessment with modern Omics technologies and machine learning analytics:

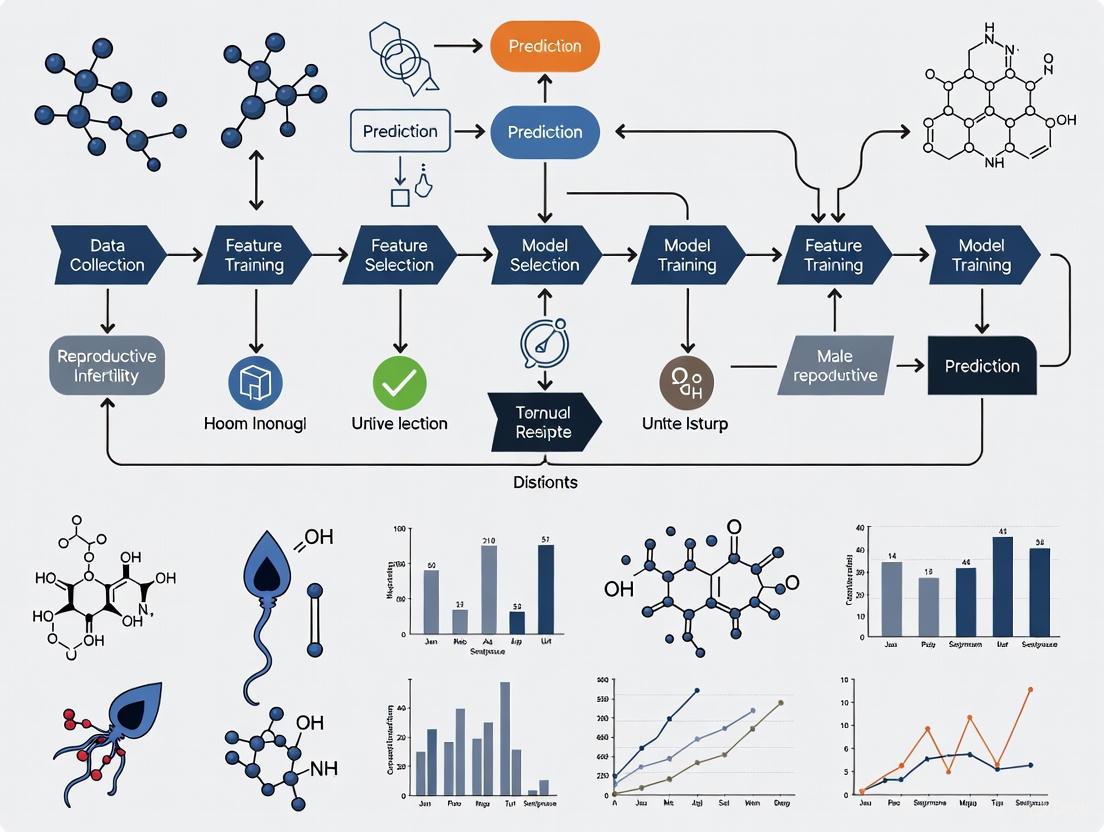

ML Framework for Male Infertility Prediction

This diagram outlines the specific components and workflow of a machine learning framework for male infertility prediction, highlighting how diverse data sources are integrated and analyzed:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Semen Sample Processing for OMICS Analysis

Principle: Proper semen sample collection and processing is fundamental for reliable downstream OMICS analysis and ML model training [4] [8].

Materials:

- Sterile wide-mouth collection containers

- Transport incubator (maintaining 37°C)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Centrifuge with temperature control

- Sperm washing medium

- Cryopreservation solutions

- Liquid nitrogen storage system

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: After 2-7 days of sexual abstinence, collect semen sample by masturbation into a sterile, wide-mouth container [8].

- Liquefaction: Allow sample to liquefy at 37°C for 15-30 minutes. Do not exceed 60 minutes to maintain sperm viability.

- Initial Analysis: Perform basic semen analysis (volume, pH, concentration, motility, morphology) according to WHO guidelines.

- Sample Separation: Centrifuge ejaculate at 500 × g for 10 minutes to separate seminal plasma from sperm cells.

- Sperm Washing: Resuspend sperm pellet in PBS or sperm washing medium and centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 minutes. Repeat twice.

- Aliquoting: Divide samples into aliquots for immediate analysis, -80°C storage, or cryopreservation.

- Cryopreservation: Mix sperm suspension with cryoprotectant medium in a stepwise fashion. Freeze using controlled-rate freezing or vitrification protocols. Store in liquid nitrogen vapor phase.

- Quality Control: Document pre-freeze and post-thaw motility for quality assurance.

Notes: Process samples within one hour of collection. For metabolomic studies, immediately freeze seminal plasma in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C to preserve metabolic profiles [3].

Protocol 2: Sperm DNA Fragmentation Analysis

Principle: Sperm DNA fragmentation is a valuable biomarker for male infertility diagnosis and ART outcome prediction, with median AUC of 0.67 [4].

Materials:

- Sperm chromatin dispersion test kit OR Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit

- Fluorescent microscope with appropriate filter sets

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Ethanol (70%, 90%, 100%)

- Proteinase K

- Low-melting-point agarose

- Lysing solution

- Staining solution (DAPI or propidium iodide)

- Mounting medium

Procedure (Sperm Chromatin Dispersion Test):

- Agarose Embedding: Mix 25-50 μL of washed sperm suspension with low-melting-point agarose to a final concentration of 1%. Place on pre-coated slides.

- Solidification: Coverslip and place slides on a cold surface (4°C) for 5 minutes to allow agarose to solidify.

- Protein Removal: Carefully remove coverslip and incubate slides in acid solution for 7 minutes, then in lysing solution for 25 minutes at room temperature.

- DNA Denaturation: Incubate slides in denaturing solution for 7 minutes followed by washing in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer.

- Dehydration: Dehydrate slides sequentially in 70%, 90%, and 100% ethanol for 2 minutes each.

- Staining: Apply DAPI or propidium iodide staining solution and mount with antifade medium.

- Microscopy: Examine under fluorescence microscope (400× magnification).

- Scoring: Evaluate 500 spermatozoa per sample. Sperm with large halos of dispersed DNA loops are classified as non-fragmented, while those with small or no halos are classified as fragmented.

Calculation: DNA Fragmentation Index (%) = (Number of sperm with fragmented DNA / Total sperm counted) × 100

Interpretation: DFI < 15% indicates excellent sperm DNA integrity; DFI 15-30% indicates moderate integrity; DFI > 30% indicates poor integrity and is associated with reduced pregnancy rates.

Protocol 3: Machine Learning Analysis of Sperm Motility Videos

Principle: Machine learning algorithms, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), can automatically predict sperm motility from video data with consistency and speed [7].

Materials:

- Phase-contrast microscope with video capture capability

- Computer with GPU acceleration

- Python programming environment with TensorFlow/PyTorch

- OpenCV library for computer vision

- Custom or commercial sperm tracking software

- Processed semen samples

Procedure:

- Video Acquisition: Capture sperm motility videos using phase-contrast microscope at 200× magnification. Maintain temperature at 37°C throughout recording.

- Preprocessing: Convert videos to appropriate format (e.g., MP4). Extract frames at consistent intervals (e.g., 30 frames per second).

- Data Labeling: Manually label a subset of videos for motility parameters (progressive, non-progressive, immotile) to create training dataset.

- Model Selection: Implement CNN architecture (e.g., ResNet, VGG) for feature extraction from video frames.

- Training: Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets. Train model using labeled data with appropriate loss function (e.g., cross-entropy).

- Validation: Evaluate model performance on validation set using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score metrics.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize learning rate, batch size, and network architecture based on validation performance.

- Testing: Assess final model performance on held-out test set. Calculate area under ROC curve (AUC) for motility prediction.

- Interpretation: Use gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) to visualize regions influencing model predictions.

Notes: Studies indicate that algorithms using only video data may outperform those combining videos with participant clinical data [7]. Ensure diverse training data to minimize demographic bias.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Male Infertility Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm Processing Media | Sperm washing medium, Human tubal fluid (HTF), Synthetic oviductal fluid (SOF) [8] | Semen sample preparation, ART procedures | Maintain sperm viability, remove seminal plasma, capacitation induction |

| Cryopreservation Solutions | Glycerol, Ethylene glycol, Synthetic cryoprotectants, Sucrose [9] | Sperm and testicular tissue preservation | Cell protection during freezing/thawing, ice crystal prevention |

| DNA Integrity Assay Kits | SCD kits, TUNEL assay kits, Comet assay reagents [4] | Sperm DNA fragmentation analysis | DNA strand break detection, nuclear protein removal, halo visualization |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | miRNA extraction kits, cDNA synthesis kits, qPCR reagents, Antibodies for protein detection [4] [8] | Biomarker discovery and validation | Nucleic acid isolation, gene expression analysis, protein quantification |

| Metabolomics Standards | Deuterated internal standards, Quality control pools, Derivatization reagents [3] | Seminal plasma metabolomic profiling | Metabolite detection normalization, quantification reference, sample preparation |

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM/F12, Fetal bovine serum, Antibiotic-antimycotic solutions [5] | Testicular cell culture, somatic cell co-culture | Support of spermatogenesis in vitro, stem cell maintenance |

| Immunoassay Kits | ELISA for TEX101, Hormone assay kits (Testosterone, FSH, LH) [4] [3] | Protein biomarker quantification, Endocrine profiling | Specific protein detection, hormonal status assessment |

Male infertility presents a substantial global health burden with significant diagnostic limitations and geographic disparities in prevalence and care access. The integration of machine learning frameworks with multi-omics approaches creates unprecedented opportunities to address these challenges through improved classification, biomarker discovery, and predictive modeling. Standardized phenotypic classification using HPO terms facilitates collaboration across institutions and promotes discovery of novel genetic causes [5]. Metabolomic profiling shows particular promise for identifying metabolic pathways and biomarkers associated with male infertility, potentially guiding targeted therapeutic development [3]. While AI adoption faces barriers including cost and training limitations, its potential to transform male infertility diagnosis and treatment continues to drive research and implementation efforts [6] [10]. The experimental protocols and reagent solutions detailed herein provide foundational methodologies for advancing this critical field of research.

Male infertility is a prevalent global health issue, affecting approximately 1 in 6 couples worldwide, with male factors contributing to about 50% of cases [11] [12]. A comprehensive understanding of its multifactorial etiology is crucial for developing effective predictive models and targeted interventions. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for investigating the clinical, lifestyle, and environmental risk factors contributing to male infertility, with specific emphasis on supporting machine learning framework development for risk prediction.

The increasing global burden of male infertility underscores the urgency of this research. From 1990 to 2021, the global number of male infertility cases and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) increased by approximately 74.66% and 74.64%, respectively [13]. By 2021, global prevalence surpassed 55 million cases with over 300,000 DALYs [12]. This growing burden exhibits significant regional disparities, with the highest age-standardized rates observed in Eastern Europe and Western Sub-Saharan Africa, reaching 1.5 times the global average [12].

Epidemiological Landscape and Quantitative Burden

Global and Regional Distribution

The burden of male infertility varies significantly across socioeconomic regions and age groups. Middle Socio-demographic Index (SDI) regions recorded the highest number of cases and DALYs in 2021, accounting for approximately one-third of the global total [13]. However, when considering age-standardized rates, the burden is most severe in low and low-middle SDI regions, including Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia [12].

Table 1: Global Burden of Male Infertility (2021)

| Metric | Global Value | Regional Variations | Temporal Trends (1990-2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence Cases | >55 million | China accounts for ~20%; Highest ASRs in Eastern Europe & Western Sub-Saharan Africa (1.5× global average) | 74.66% increase globally |

| DALYs | >300,000 | South and East Asia contribute ~50% of global burden | 74.64% increase globally |

| Age-Standardized Prevalence Rate (ASPR) | Varies by region | Most rapid increases in low and low-middle SDI regions | Stable/declining in China since 2008; Increasing globally |

| Key Age Group | 35-39 years (highest prevalence) | Global pattern consistent across regions | Population growth primary driver globally; aging more significant in China |

Age-Specific Patterns and Contributing Factors

From an age subgroup perspective, the 35-39 age group reported the highest number of male infertility cases in 2021 [13]. This age distribution corresponds with patterns of age-related fertility decline, where paternal age contributes to decreased semen quality, increased sperm DNA fragmentation, and elevated risk of genetic abnormalities in offspring. Epidemiological studies consistently show a dose-response relationship between semen parameters and mortality risk, with men with severe sperm abnormalities facing significantly higher health risks [14].

Risk Factor Assessment: Clinical, Lifestyle, and Environmental Dimensions

Male infertility arises from complex interactions between clinical conditions, lifestyle factors, and environmental exposures. Understanding these multifactorial influences is essential for comprehensive risk assessment.

Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors

Clinical determinants of male infertility encompass a range of medical conditions, genetic abnormalities, and physiological disruptions. Varicocele represents a major contributor, affecting 15% of all men but impacting 25-35% of men with primary infertility and 50-80% of men with secondary infertility [15]. Azoospermia (complete absence of sperm) affects 10-15% of infertile men and approximately 1% of the general male population [15].

Genetic factors significantly influence male infertility risk. Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) exemplifies a genetic cause of azoospermia that also predisposes to metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and certain malignancies [14]. Other genetic associations include Y-chromosome microdeletions, CFTR gene mutations in congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens, and mutations in the androgen receptor gene [16].

Table 2: Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors for Male Infertility

| Category | Specific Factor | Prevalence/Impact | Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Conditions | Varicocele | 25-35% primary infertility; 50-80% secondary infertility | Increased scrotal temperature, oxidative stress |

| Azoospermia | 10-15% of infertile men; 1% general population | Obstructive or non-obstructive etiologies | |

| Infections (epididymitis, STIs) | Contribute to inflammatory damage | Ductal obstruction, impaired spermatogenesis | |

| Testicular trauma/cancer treatments | Direct testicular damage | Germ cell depletion, hormonal disruption | |

| Genetic Factors | Klinefelter syndrome | Most common chromosomal abnormality | Testicular hyalinization, testosterone deficiency |

| Y-chromosome microdeletions | 5-10% severe oligospermia/azoospermia | Impaired spermatogenesis genes | |

| CFTR mutations | Associated with CBAVD | Developmental ductal abnormalities | |

| Androgen receptor mutations | Spectrum from infertility to AIS | Hormonal signaling disruption | |

| Endocrine Disorders | Hypogonadism | Primary or secondary forms | Direct spermatogenic disruption |

| Low testosterone | Frequent in testicular dysfunction | Obesity, insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease |

Lifestyle and Environmental Risk Factors

Lifestyle choices and environmental exposures represent modifiable risk factors for male infertility. The Australian Male Infertility Exposure (AMIE) study protocol outlines a comprehensive approach to investigating these factors from teenage years onwards [17]. Key lifestyle factors include smoking, alcohol consumption, sedentary behavior, and psychological stress. Environmental exposures encompass endocrine-disrupting chemicals, air pollution, and occupational hazards [17] [14].

Chronic psychological stress, commonly reported among infertile men, may contribute to health-compromising behaviors and directly impact reproductive function through neuroendocrine pathways [14]. The relationship between lifestyle factors and infertility is complex, with multiple potential mechanisms including oxidative stress, hormonal disruption, epigenetic modifications, and direct cellular damage to spermatogenic cells.

Experimental Protocols for Risk Factor Assessment

Comprehensive Phenotyping Protocol: The AMIE Study Framework

The Australian Male Infertility Exposure (AMIE) study provides a robust methodological framework for investigating lifestyle and environmental risk factors for unexplained male infertility [17].

Study Design:

- Case-Control Design: 500 cases (idiopathic male infertility) vs. 500 controls (female factor infertility only)

- Recruitment Setting: Multiple fertility clinics across Australia

- Inclusion Criteria: Men aged 18-50 years with female partner <42 years

- Matching Criteria: Age and socioeconomic status

Data Collection Methods:

- Standardized Survey Instrument:

- General health history

- Lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol, nutrition, physical activity)

- Environmental exposures (occupational, residential, plastic use)

- Temporal assessment: from teenage years to present

Medical Record Abstraction:

- Reproductive history and prior evaluations

- Semen analysis parameters

- Hormonal profiles (testosterone, FSH, LH)

- Physical examination findings

Biological Specimen Collection:

- Saliva (all participants)

- Blood and urine (optional)

- Long-term storage for genetic/epigenetic analysis

Analytical Approach:

- Between-group comparisons of exposure prevalence

- Multilevel modeling to account for clinic-level clustering

- Dose-response relationships for key exposures

- Integration of phenotypic and biomarker data

Laboratory Assessment of Semen Parameters

Comprehensive semen analysis extends beyond basic WHO parameters to include advanced functional and molecular assessments.

Basic Semen Analysis Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Standardized abstinence period (2-5 days)

- Macroscopic Evaluation: Volume, pH, viscosity, liquefaction

- Microscopic Assessment:

- Concentration (hemocytometer chamber)

- Motility (progressive, non-progressive, immotile)

- Morphology (strict Kruger criteria)

Advanced Sperm Function Tests:

- Sperm DNA Fragmentation:

- Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay (SCSA)

- Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)

- Sperm Chromatin Dispersion (SCD)

- Oxidative Stress Markers:

- Reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurement

- Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of seminal plasma

- Sperm Vitality Assessment:

- Eosin-nigrosin staining

- Hypo-osmotic swelling test

Signaling Pathways and Mechanistic Relationships

The pathophysiology of male infertility involves multiple interconnected biological pathways. The following diagram illustrates key mechanistic relationships between risk factors and infertility outcomes:

Research Reagent Solutions for Male Infertility Investigation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Male Infertility Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Research Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semen Analysis Kits | LensHooke X1 PRO [11] | Automated semen analysis (concentration, motility) | High correlation with manual methods; AI-powered |

| Sperm DNA fragmentation kits (SCD, TUNEL) | Sperm DNA integrity assessment | AI-assisted analysis reduces variability [11] | |

| Hormonal Assays | Testosterone, FSH, LH ELISA kits | Endocrine profile assessment | Critical for hypogonadism evaluation |

| SHBG, Estradiol, Prolactin assays | Comprehensive hormonal mapping | Reveals endocrine disruption patterns | |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Y-chromosome microdeletion PCR panels | Genetic screening | For severe oligozoospermia/azoospermia [16] |

| Karyotyping & CFTR mutation detection | Genetic diagnosis | Identifies known genetic causes | |

| Oxidative stress markers (ROS, TAC) | Seminal plasma analysis | Quantifies oxidative stress burden | |

| Cell Culture Media | Sperm washing & preparation media | ART procedures | Maintains sperm viability and function |

| Cryopreservation solutions | Sperm banking | Vital for fertility preservation | |

| Immunohistochemistry Reagents | Testicular biopsy markers | Spermatogenic evaluation | Identifies maturation arrest patterns |

| Apoptosis detection kits (caspase assays) | Germ cell death quantification | Measures spermatogenic efficiency |

Machine Learning Framework Integration

Data Requirements for Predictive Modeling

Development of robust machine learning frameworks for male infertility prediction requires structured integration of multidimensional data:

Clinical and Phenotypic Data Layer:

- Semen parameters (concentration, motility, morphology)

- Hormonal profiles (testosterone, FSH, LH, prolactin)

- Medical history (varicocele, infections, surgeries)

- Physical examination findings (testicular volume, consistency)

Exposure and Lifestyle Data Layer:

- Lifetime environmental exposure assessment [17]

- Smoking, alcohol, and substance use history

- Occupational hazards and chemical exposures

- Psychological stress measures and mental health history

Genetic and Molecular Data Layer:

- Genetic screening results (karyotype, Y-microdeletions)

- Sperm DNA fragmentation indices

- Epigenetic markers (sperm methylation patterns)

- Seminal plasma proteomic and metabolomic profiles

AI Applications in Male Infertility Assessment

Artificial intelligence approaches are transforming male infertility evaluation with several demonstrated applications:

Semen Analysis Automation:

- Deep convolutional neural networks for sperm classification achieve 94% accuracy in WHO categorization [11]

- AI-powered motility assessment shows strong correlation (r=0.88) with manual evaluation [11]

- Morphological classification systems reach 90.73% accuracy [11]

Advanced Sperm Selection:

- The STAR (Sperm Tracking and Recovery) technology combines AI, microfluidics, and robotics to detect viable sperm in azoospermic samples, finding 44 sperm in one hour from samples where skilled technicians found none after two days [18]

- AI systems can detect sperm in samples with counts as low as 2-3 cells per entire sample [18]

Predictive Modeling:

- Machine learning algorithms identify hematologic variables related to semen parameters with 0.69 accuracy [11]

- Models predicting semen quality from modifiable lifestyle factors show AUC between 0.648-0.697 [11]

Male infertility represents a complex multifactorial condition with significant and growing global burden. The intricate interplay between clinical, genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors necessitates comprehensive assessment frameworks and sophisticated analytical approaches. The experimental protocols and application notes detailed in this document provide a foundation for systematic investigation of male infertility risk factors.

The integration of these multidimensional data streams into machine learning frameworks offers promising avenues for improved risk prediction, personalized intervention strategies, and ultimately, enhanced clinical outcomes for affected individuals. Future research directions should prioritize longitudinal assessment of lifetime exposures, integration of multi-omics data, and development of validated AI tools for clinical deployment.

The application of machine learning (ML) to male infertility prediction requires a foundation of robust, multidimensional data. Traditional diagnostics have relied heavily on standard semen analysis, but the multifactorial nature of male infertility demands a more comprehensive approach. Modern frameworks integrate conventional semen parameters with hormonal profiles, advanced molecular biomarkers, and genetic factors to create a holistic data ecosystem. This integration enables ML algorithms to identify complex, non-linear patterns that escape conventional statistical analysis, ultimately improving diagnostic accuracy, treatment selection, and prognostic prediction [19] [4] [20]. The median accuracy of ML models in predicting male infertility is reported to be 88%, surpassing traditional methods [20].

The data landscape for male infertility can be categorized into several distinct but interconnected types, each providing a unique piece of the diagnostic puzzle. The following sections and Table 1 detail these core data types, their normal values, and their clinical significance, forming the essential variables for any predictive modeling endeavor.

Table 1: Core Semen Analysis Parameters and Normal Values According to WHO Guidelines [21]

| Semen Parameter | Normal Value | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | 1.4 - 6.2 mL | Hypospermia (<1.4 mL) may indicate obstruction, retrograde ejaculation, or androgen deficiency. |

| Sperm Concentration | ≥ 15 million/mL | Primary indicator of testicular sperm production. |

| Total Sperm Count | ≥ 39 million | A more reliable indicator of testicular function than concentration alone. |

| Total Motility | ≥ 42% | Crucial for natural conception, indicates sperm movement capability. |

| Progressive Motility | ≥ 30% | Reflects the population of sperm with purposeful forward movement. |

| Morphology (Normal Forms) | ≥ 4% | Assesses the percentage of sperm with a typical structure. |

| Vitality | ≥ 54% | Differentiates between immotile live sperm and dead sperm; indicates necrospermia if low. |

| pH | 7.2 - 7.8 | Imbalances can suggest infection (high pH) or obstructions (low pH). |

Protocol 1: Conventional Semen and Hormonal Profiling

Experimental Workflow for Basic Diagnostic Data Collection

The initial assessment of male fertility relies on standardized protocols for collecting and analyzing fundamental semen and hormonal data. This workflow ensures consistency and reliability, which is critical for building high-quality datasets for machine learning.

Detailed Methodologies

1. Patient Preparation and Semen Collection:

- Participants should observe a sexual abstinence period of 2 to 7 days prior to sample collection. Consistency in the abstinence period for subsequent tests is crucial for reliable comparisons [21].

- Samples are collected by masturbation into a sterile, wide-mouthed container. To ensure sample integrity, the time from collection to the initiation of analysis must be less than 60 minutes, and the sample must be maintained between 20°C and 37°C during transport [19] [21].

2. Macroscopic and Microscopic Semen Analysis:

- Macroscopic Evaluation: This includes assessment of liquefaction (complete within 60 minutes), appearance (light cream/gray), pH (7.2-7.8), and volume (1.4-6.2 mL). Abnormal viscosity is noted when drops form a thread longer than 2 cm [19] [21].

- Microscopic Evaluation: Sperm concentration and total count are manually assessed using an improved Neubauer hemocytometer. Motility (progressive, non-progressive, immotile) is evaluated under a phase-contrast microscope. Sperm morphology is determined from Papanicolaou-stained smears, with a strict criterion of ≥4% normal forms considered typical [19] [21]. Vitality is assessed using eosin staining, particularly when motility is below 40% [21].

3. Hormonal Profiling:

- Venous blood is collected in the morning (7:30-9:00 AM) to account for diurnal rhythms. Key reproductive hormones—Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), Luteinizing Hormone (LH), total Testosterone, Prolactin (PRL), and Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH)—are quantified using the electrochemiluminescence (ECLIA) method. This method uses biotinylated monoclonal antibodies and ruthenium-labeled complexes in a sandwich assay format, with streptavidin-bound microparticles for binding [19]. This data is critical, as subjects with abnormal hormonal levels or decreased testicular volume (<12 mL) often show impaired conventional semen parameters and higher sperm DNA fragmentation [19].

Protocol 2: Advanced and Molecular Biomarker Analysis

Workflow for Omics and DNA Integrity Assessment

Beyond conventional analysis, advanced biomarkers provide a deeper insight into sperm function and genetic integrity. These biomarkers are particularly valuable for explaining idiopathic infertility and predicting the success of Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART). The workflow integrates various "Omics" technologies to build a comprehensive biomarker profile.

Detailed Methodologies

1. Sperm DNA Fragmentation (SDF) Analysis via SCD Test:

- The Sperm Chromatin Dispersion (SCD) test is performed using a commercial kit (e.g., Halosperm G2). After sample processing, sperm are embedded in an agarose microgel on a slide, subjected to an acid denaturation step, and then lysed to remove nuclear proteins. Sperm with non-fragmented DNA display large or medium-sized halos of dispersed DNA loops after staining. In contrast, sperm with fragmented DNA show small halos or no halos [19].

- A minimum of 300 sperm cells are counted under a microscope. An SDF level of ≤15% is considered a low level of DNA damage and correlates with high fertility potential. An SDF of >15–30% is moderate and may reduce chances of pregnancy, while an SDF >30% is high and is strongly associated with an increased risk of reproductive failure and pregnancy loss, even with Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) [19].

2. Omics Biomarker Profiling:

- Genomics/Epigenomics: This involves screening for karyotypic abnormalities, Y-chromosome microdeletions, and specific gene mutations [22] [23]. DNA methylation patterns are also emerging as potential biomarkers.

- Transcriptomics: Analysis of non-coding RNAs in semen, such as miR-34c-5p, shows excellent predictive value for male infertility (median AUC = 0.78) [4].

- Proteomics: Protein-based assays are gaining traction. The level of TEX101 in seminal plasma, for instance, has shown excellent diagnostic potential (median AUC = 0.69) for infertility [4] [23].

- Metabolomics: The profile of metabolites in seminal plasma can serve as a biomarker for sperm quality and fertilizing capacity. Metabolomic profiles generally show better predictive value than individual metabolites [4].

Table 2: Advanced Biomarkers for Male Infertility Assessment [19] [4] [23]

| Biomarker Category | Specific Biomarker/Assay | Interpretation & Clinical Utility | Predictive Value (AUC Median) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Integrity | Sperm DNA Fragmentation (SCD) | >30%: High risk of reproductive failure & miscarriage. Guides choice between IVF and ICSI. | 0.67 |

| DNA Damage Marker | γH2AX | Level indicates DNA strand breaks; shows good predictive value for infertility diagnosis. | 0.93 |

| Transcriptomics | miR-34c-5p | A robust RNA biomarker in semen for assessing male fertility status. | 0.78 |

| Proteomics | TEX101 (Seminal Plasma) | Protein biomarker with excellent diagnostic potential for male infertility. | 0.69 |

| Genetic Factors | Karyotype, Y-microdeletions | Identifies well-known genetic causes of azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia. | N/A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols outlined above rely on a suite of specific reagents and tools. The following table details essential items for establishing these assays in a research setting.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Male Infertility Biomarker Analysis

| Research Reagent / Kit | Manufacturer (Example) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Halosperm G2 Kit | Halotech DNA, Spain | To perform the Sperm Chromatin Dispersion (SCD) test for quantifying sperm DNA fragmentation. |

| Cobas e801 Analytical Unit & Reagents | Roche Diagnostics, Germany | To measure reproductive hormone levels (FSH, LH, Testosterone, PRL, TSH) using the ECLIA method. |

| LeucoScreen Kit | FertiPro N.V., Belgium | To detect and quantify peroxidase-positive leukocytes in semen (Endtz test). |

| Papanicolaou Stain Set | Aqua-Med, Poland | To stain sperm smears for the detailed morphological assessment of spermatozoa. |

| Improved Neubauer Hemocytometer | Heinz Hernez, Germany | To manually determine sperm concentration and concentration of round cells. |

| Specific Antibody Panels | Various | For proteomic analysis of seminal plasma biomarkers (e.g., antibodies against TEX101, ACRV1). |

| RNA Extraction & qPCR Kits | Various | For transcriptomic analysis of non-coding RNAs (e.g., miR-34c-5p) from semen samples. |

| Oct-5-ynamide | Oct-5-ynamide|High-Quality Ynamide Reagent for Research | Oct-5-ynamide is a valuable ynamide building block for synthetic chemistry research, enabling complex molecule assembly. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| 2,3-Dimethyl-Benz[e]indole | 2,3-Dimethyl-Benz[e]indole, MF:C14H13N, MW:195.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Machine Learning Frameworks

The true power of these diverse data sources is unlocked through integration into machine learning frameworks. The structured data from protocols 1 and 2 form the feature vectors for ML models. Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of this approach, with algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and ensemble methods like SuperLearner achieving exceptionally high predictive performance (AUC of 96-97%) for male infertility risk [22]. Sperm concentration, FSH, and LH levels have been identified as among the most important risk factors in these models [22].

Furthermore, ML techniques, including convolutional neural networks, have been successfully applied to automate and enhance the analysis of raw clinical data, such as sperm motility videos, providing rapid and consistent assessments that can be directly fed into predictive models [24] [20]. The median accuracy of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) in this domain is reported to be 84% [20]. This multi-faceted, data-driven approach represents the future of male infertility diagnosis and prognosis, moving beyond isolated parameter analysis to a holistic, predictive understanding of male reproductive health.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Transforming Andrological Diagnostics

Male infertility affects approximately one in six couples globally, with male factors contributing to about half of all infertility cases [11]. The current diagnostic paradigm, heavily reliant on conventional semen analysis, is often subjective, labor-intensive, and limited in its ability to predict treatment outcomes [11] [25]. Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), is poised to revolutionize this field by introducing objectivity, automation, and powerful predictive capabilities. Within the framework of male infertility prediction research, AI offers the potential to move beyond descriptive analysis to prognostic modeling, enhancing clinical decision-making and personalizing patient care [26] [27]. This document outlines the specific applications, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions underpinning this transformation, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of computational science and reproductive medicine.

AI Applications in Diagnostic and Prognostic Prediction

AI algorithms are being deployed across the andrological diagnostic spectrum, from initial semen assessment to predicting the success of surgical and assisted reproductive interventions.

Semen Analysis and Sperm Quality Assessment

Computer-Aided Sperm Analysis (CASA) systems, enhanced by AI, allow for the high-throughput, objective assessment of sperm concentration, motility, and morphology [26]. Deep learning models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in classifying sperm heads and identifying morphological defects.

Table 1: Performance of Selected AI Models in Semen Analysis

| AI Task | AI Method | Reported Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm Morphology Classification | Faster Region-CNN | 97.37% accuracy | [11] |

| Sperm Motility Classification | Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) | Strong correlation with manual assessment (r=0.88-0.89) | [11] |

| Sperm Vitality Prediction | Region-Based CNN | Pearson correlation: 0.969 | [11] |

| Sperm DNA Fragmentation Assessment | AI-powered microscopic assay | Strong agreement with manual method (r=0.97) | [11] |

Prediction of Surgical and ART Outcomes

Machine learning models are increasingly used to predict the success of various andrological treatments, helping to guide clinical decisions and manage patient expectations.

Table 2: AI Models for Predicting Therapeutic Outcomes in Andrology

| Clinical Scenario | AI Model | Key Predictive Features | Reported Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Varicocelectomy Improvement | Random Forest | Serum FSH, Bilateral Varicocele | 87% predictive accuracy for improvement | [26] |

| Sperm Retrieval in NOA | Gradient-Boosted Trees | Patient weight, age, FSH levels | Superior to logistic regression | [26] |

| Male Fertility Risk Screening | Automated ML (AutoML) | FSH, T/E2 ratio, LH | AUC: 74.2% - 77.2% | [25] |

| ART Outcomes in YCMD | Web-based ML Algorithm | Type of Y-chromosome deletion | High accuracy for SRR, CPR, LBR | [28] |

| IVF Live Birth Prediction | Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Woman's age, gonadotropin dose, endometrial thickness, embryo quality | Sensitivity: 76.7%, Specificity: 73.4% | [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Key AI Applications

Protocol 1: Developing an AI Model for Male Infertility Risk from Serum Hormones

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating a predictive model using only serum hormone levels, bypassing the need for initial semen analysis [25].

Workflow Diagram: Serum-Based Infertility Risk Prediction

Detailed Procedure:

- Data Collection: Compile a retrospective dataset from electronic health records, including patient age and serum levels of LH, FSH, PRL, testosterone, and estradiol (E2). Calculate the testosterone-to-estradiol (T/E2) ratio. A large cohort size (e.g., n=3662) is recommended for robust model training [25].

- Data Labeling (Ground Truth): Label each patient's data based on the results of a conventional semen analysis performed according to WHO guidelines. A binary classification (e.g., "normal" vs. "abnormal") can be defined based on a calculated threshold such as total motile sperm count (e.g., 9.408 × 10^6) [25].

- Data Preprocessing: Clean the data to handle missing values and outliers. Normalize the hormone level data to a common scale to prevent features with larger numerical ranges from dominating the model.

- Model Training: Utilize automated machine learning (AutoML) platforms (e.g., Prediction One, AutoML Tables) or classic ML libraries (e.g., Scikit-learn). Split the dataset into training (70-80%) and testing (20-30%) sets. Train multiple algorithms, such as Random Forest or Gradient-Boosted Trees, to identify the best performer [25].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Analyze the trained model to determine which hormonal parameters contribute most to the prediction. Studies consistently identify FSH as the most important feature, followed by T/E2 ratio and LH [25].

- Model Validation: Evaluate the model's performance on the held-out test set using metrics such as Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, precision, recall, and F-value.

Protocol 2: AI-Assisted Sperm Morphology Analysis using Deep Learning

This protocol details the use of a deep learning model for the automated and standardized classification of sperm morphology [11].

Workflow Diagram: Deep Learning for Sperm Morphology

Detailed Procedure:

- Image Acquisition: Capture high-resolution digital images of sperm smears using a standardized optical microscope equipped with a digital camera. Ensure consistent staining (e.g., Papanicolaou) and slide preparation to minimize technical variation.

- Data Annotation (Ground Truth): Have experienced andrologists label a large set of sperm images according to WHO criteria or the Strict Tygerberg criteria. Labels should include classifications such as "normal," "head defect," "neck defect," "tail defect," and "cytoplasmic droplet" [11].

- Model Architecture and Training: Implement a Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN), such as a Faster R-CNN or a U-Net architecture. The U-Net is particularly effective for image segmentation tasks, such as precisely identifying the sperm head, acrosome, and nucleus, achieving Dice coefficients above 0.94 [11]. Train the model using the annotated image dataset.

- Model Validation: Validate the model's classification performance against a test set of expert-annotated images. Report standard metrics including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score. The model should be able to perform at an accuracy exceeding 90% for classifying normal versus abnormal sperm [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for AI-Driven Andrology Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| CASA System with AI | Automated sperm motility and kinematics analysis. Reduces inter-operator variability. | Systems provide parameters like VCL, VSL, and ALH for ML models [26]. |

| Flow Cytometry Reagents | Assessment of biofunctional sperm parameters (DNA fragmentation, MMP, oxidative stress). | Kits for SCSA, TUNEL assay. Software with ML tools (FlowJo) enables single-cell analysis [26]. |

| AI-Optical Microscope | Integrated hardware/software for automated semen analysis. | LensHooke X1 PRO; can be correlated with manual methods for concentration and motility [11]. |

| Hormone Assay Kits | Provide the quantitative input features (LH, FSH, Testosterone) for serum-based prediction models. | ELISA or chemiluminescence kits are standard. High precision is critical for model accuracy [25]. |

| Standardized Staining Kits | (e.g., Papanicolaou, Diff-Quik) for sperm morphology preparation. | Essential for creating consistent, high-quality image datasets for training deep learning models [11]. |

| AI Software Frameworks | Libraries for developing and training custom machine learning models. | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn. AutoML platforms (e.g., Google AutoML Tables) can streamline model development [25]. |

| 2'-Aminobiphenyl-2-ol | 2'-Aminobiphenyl-2-ol, MF:C12H11NO, MW:185.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,2-Dibromooctan-3-OL | 1,2-Dibromooctan-3-OL|C8H16Br2O|CAS 159832-04-9 | 1,2-Dibromooctan-3-OL (C8H16Br2O) is a high-purity organobromine compound for research use only (RUO). It is not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. |

The integration of artificial intelligence into andrological diagnostics marks a significant shift towards data-driven, predictive, and personalized medicine. The applications detailed in these notes—from automated semen analysis and serum-based risk prediction to outcome forecasting for ART—demonstrate the potential of ML frameworks to directly address critical challenges in male infertility prediction research. While challenges regarding data standardization, model interpretability, and clinical validation remain, the continued development and refinement of these protocols and tools promise to enhance diagnostic accuracy, optimize treatment selection, and ultimately improve patient outcomes in andrology.

Machine Learning Architectures and Algorithms for Fertility Assessment

The application of machine learning (ML) in male infertility research is transforming the diagnosis and prognosis of a condition that affects millions of couples globally, with male factors contributing to 20-30% of infertility cases [29]. Industry-standard classifiers including Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) offer powerful tools for analyzing complex biomedical data to predict infertility outcomes, optimize treatment selection, and uncover subtle patterns in clinical and laboratory parameters. These algorithms excel at capturing intricate, nonlinear relationships within datasets, enabling researchers to identify subtle patterns in hormonal profiles, semen parameters, and demographic factors that may contribute to infertility [30]. This document provides application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these classifiers within a comprehensive ML framework for male infertility prediction research.

Classifier Comparison and Performance Metrics

Algorithmic Characteristics and Theoretical Foundations

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Industry-Standard Classifiers

| Classifier | Algorithmic Approach | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Overfitting Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Ensemble bagging with multiple independent decision trees [31] | Robust to outliers, handles high-dimensional data, provides feature importance scores [31] | Can be computationally expensive with large numbers of trees, may not achieve highest possible accuracy [31] | Random feature subsets, bootstrap sampling, model averaging [31] |

| XGBoost | Sequential ensemble building with gradient boosting, trees correct previous errors [31] | High predictive accuracy, efficient handling of missing values, built-in regularization [31] | Requires more careful parameter tuning, sequential training limits parallelization [31] | L1/L2 regularization, tree depth constraints, minimum child weight parameters [31] |

| SVM | Finds optimal hyperplane to separate classes with maximum margin [29] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, memory efficient, versatile with kernel functions [29] | Can be computationally intensive with large datasets, sensitive to kernel choice and parameters [29] | Regularization parameter C, kernel selection, margin optimization [29] |

| ANN | Network of interconnected nodes inspired by biological neural systems [30] | Excellent at learning complex non-linear relationships, handles diverse data types | Requires large datasets, computationally intensive, "black box" interpretation challenges [30] | Dropout layers, regularization techniques, early stopping, network architecture constraints [30] |

Performance Metrics in Male Infertility Applications

Table 2: Documented Performance of Classifiers in Male Infertility Research

| Classifier | Application Context | Reported Performance | Data Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | IVF success prediction [29] | AUC: 84.23% on 486 patients [29] | Clinical patient data, hormonal parameters |

| Random Forest | Clinical pregnancy rate prediction [30] | Highest accuracy among compared models | Age, FSH, endometrial thickness [30] |

| XGBoost | Cumulative live birth rate prediction for IVF/ICSI [32] | Not explicitly quantified in abstract | Tubal and male infertility factors |

| XGBoost | Stunting prediction (relevant health application) [33] | Accuracy: 87.83%, Precision: 85.75%, Recall: 91.59% | Imbalanced clinical data with SMOTE processing [33] |

| SVM | Sperm morphology analysis [29] | AUC: 88.59% on 1400 sperm images [29] | Computerized sperm imagery |

| SVM | Sperm motility classification [29] | Accuracy: 89.9% on 2817 sperm [29] | Motility tracking data |

| ANN | Male infertility prediction (systematic review) [20] | Median accuracy: 84% across multiple studies | Hormonal, demographic, and clinical parameters |

| ANN | Predicting sperm presence in non-obstructive azoospermia [34] | 80.8% correct predictions, Sensitivity: 68% | Age, infertility duration, hormone levels, testicular volume [34] |

| Gradient Boosting Trees | Non-obstructive azoospermia sperm retrieval [29] | AUC: 0.807, Sensitivity: 91% on 119 patients [29] | Clinical and diagnostic parameters |

Systematic reviews indicate that ML models achieve a median accuracy of 88% in predicting male infertility, with ANN models specifically demonstrating a median accuracy of 84% across studies [20]. The performance advantage of XGBoost has been demonstrated in healthcare contexts beyond infertility, where it achieved 87.83% accuracy in stunting prediction, outperforming RF (84.56%) and SVM (68.59%) [33].

Experimental Protocols for Male Infertility Prediction

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering Protocol

Protocol 1: Standardized Data Preprocessing Workflow

Data Collection and Integration

- Collect hormonal parameters (FSH, LH, testosterone, prolactin, AMH) [30] [34]

- Document demographic factors (age, BMI, duration of infertility) [30] [34]

- Include semen analysis parameters (count, motility, morphology) from manual or CASA systems [29]

- Aggregate medical history factors (varicocele, genetic factors, lifestyle influences) [29]

Data Cleaning and Imputation

- Address missing values using k-nearest neighbors (KNN) imputation for continuous variables

- Apply mode imputation for categorical variables with less than 5% missingness

- Remove cases with more than 20% missing data points

- Identify and address outliers using interquartile range (IQR) method

Data Normalization and Balancing

- Apply standardization (Z-score normalization) to continuous features

- Utilize Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) for class imbalance [33]

- Implement one-hot encoding for categorical variables

- Create training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) splits with stratified sampling

Classifier Implementation and Training Protocol

Protocol 2: Model-Specific Training Procedures

Random Forest Implementation

- Initialize with 100-500 decision trees, increasing until performance plateaus

- Set

max_featuresto 'sqrt' for classification tasks - Use

min_samples_splitof 5 andmin_samples_leafof 1 for detailed segmentation - Enable bootstrap sampling and out-of-bag error estimation

- Implement nested cross-validation to avoid overfitting

XGBoost Implementation

- Set initial learning rate (eta) to 0.1, gradually decreasing to 0.01 for fine-tuning

- Apply L1 (0.1) and L2 (0.9) regularization to control complexity [31]

- Limit

max_depthto 6-8 levels to prevent overfitting [31] - Set

min_child_weightto 3 for balanced leaf assignment - Use early stopping rounds of 10-20 with validation set monitoring

SVM Implementation

- Conduct hyperparameter search for regularization parameter C (range 0.1-100)

- Evaluate kernel functions (linear, polynomial, RBF) with cross-validation

- Optimize gamma parameter for RBF kernel using grid search

- Scale all features to [0,1] range before training

- Implement one-vs-rest strategy for multi-class problems

ANN Implementation

- Design architecture with input layer matching feature dimensions

- Implement 2-3 hidden layers with decreasing nodes (e.g., 64, 32, 16)

- Apply ReLU activation for hidden layers, sigmoid/softmax for output

- Utilize dropout layers (rate 0.2-0.5) between hidden layers [30]

- Implement early stopping with patience of 15-20 epochs

Model Evaluation and Validation Protocol

Protocol 3: Comprehensive Performance Assessment

Performance Metric Calculation

Statistical Validation

- Execute k-fold cross-validation (k=5-10) with stratified sampling

- Perform McNemar's test for paired classifier comparison

- Calculate 95% confidence intervals for performance metrics

- Implement permutation tests for feature importance validation

Clinical Relevance Assessment

- Determine clinical sensitivity and specificity at optimal thresholds

- Calculate number needed to treat (NNT) for treatment guidance

- Perform decision curve analysis to evaluate clinical utility

- Assess calibration in the large and calibration slope

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Male Infertility Prediction Pipeline

Classifier Architecture Comparison

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for ML-Based Infertility Studies

| Category | Specific Item | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormonal Assays | FSH, LH, Testosterone ELISA Kits | Quantify serum hormone levels for feature input [30] [34] | Critical for ANN models predicting sperm presence [34] |

| Semen Analysis | Computer-Assisted Sperm Analysis (CASA) | Automated sperm motility and morphology assessment [29] | Provides high-quality input for SVM motility classification [29] |

| Semen Analysis | DNA Fragmentation Index (DFI) Kits | Assess sperm DNA integrity as predictive feature [29] | Emerging parameter for ML prediction models |

| Imaging Systems | High-Speed Microscopy with Digital Capture | Acquire sperm videos for convolutional neural networks [24] | Enables deep learning approaches with 81-86% accuracy [20] |

| Biochemical Tests | Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) Assays | Measure ovarian reserve (female partner) and testicular function [30] | Included in hybrid models combining hormonal and demographic data [30] |

| Data Processing | Python Scikit-Learn Library | Implementation of RF, SVM, and gradient boosting models | Essential for reproducible ML pipeline development |

| Data Processing | TensorFlow/PyTorch Frameworks | Deep learning implementation for ANN architectures [30] | Required for complex neural network models |

| Sample Processing | Microfluidic Sperm Sorting Chips | Prepare samples for AI-assisted sperm selection [18] | Used in conjunction with ML analysis systems |

The implementation of industry-standard classifiers RF, SVM, ANN, and XGBoost within a male infertility prediction framework requires careful attention to data quality, appropriate algorithm selection, and rigorous validation. Current evidence suggests that ensemble methods like XGBoost and Random Forest often achieve superior performance for structured clinical data, while SVM excels in image-based sperm analysis, and ANN provides robust handling of complex non-linear relationships in multimodal data. Researchers should select classifiers based on their specific data characteristics, with XGBoost recommended for maximum predictive accuracy, Random Forest for robust baseline performance, SVM for image and high-dimensional data, and ANN for complex pattern recognition in multimodal datasets. Future directions should focus on developing hybrid models [30], improving explainability for clinical adoption, and conducting multicenter validation studies to ensure generalizability across diverse patient populations.

Male infertility is a significant health concern, contributing to 20-30% of all infertility cases and affecting an estimated 30 million men globally [35]. The diagnostic landscape has long been hampered by the limitations of traditional semen analysis, which relies on manual assessment leading to substantial inter-observer variability and poor reproducibility [35]. Within this context, non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) represents the most severe form, impacting approximately 1% of the male population and 10-15% of infertile men [35]. The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines emphasize the critical importance of a thorough urological assessment for all men presenting with fertility problems, recently incorporating new sections on exome sequencing and probiotic treatment in their 2025 update [36].

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning and deep learning, has emerged as a transformative technology for addressing these diagnostic challenges. AI algorithms can enhance diagnostic accuracy by automating sperm evaluation and identifying abnormal sperm characteristics with greater consistency than manual methods [35]. However, standard artificial neural networks (ANNs) often face optimization challenges, including convergence to local minima and suboptimal parameter configuration [37] [38]. Hybrid approaches that combine neural networks with nature-inspired optimization algorithms such as Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) and Genetic Algorithms (GA) offer promising solutions to these limitations, potentially revolutionizing male infertility prediction and management within assisted reproductive technology (ART) contexts.

Technical Foundation of Hybrid Models

Neural Network Architectures for Medical Data

Artificial Neural Networks are computational algorithms modeled after biological nervous systems, containing interconnected processing elements (neurons) that work in harmony to solve complex problems [37]. In medical applications such as male infertility research, several ANN architectures have demonstrated particular utility:

- Feed-forward Neural Networks: Commonly used for pattern classification tasks including sperm morphology analysis and treatment outcome prediction [38]. These networks process information in one direction from input to output layers.

- Multi-layer Perceptrons (MLP): Applied in male infertility contexts for predicting IVF success and classifying sperm quality parameters with demonstrated accuracy up to 89.9% for motility analysis [35].

- Deep Neural Networks: Utilize multiple hidden layers to automatically extract hierarchical features from complex data, potentially capturing subtle patterns in sperm imagery and patient clinical profiles.

The performance of these neural networks depends critically on their configuration, including the number of hidden layers, neurons per layer, learning rates, and activation functions [37]. Selecting optimal parameters through manual trial-and-error approaches is often time-consuming and frequently yields suboptimal results, creating the need for sophisticated optimization techniques.

Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms

Nature-inspired optimization algorithms mimic natural processes to solve complex computational problems. For neural network optimization in medical applications, two approaches have shown significant promise:

- Genetic Algorithms (GA): Evolutionary algorithms that apply principles of natural selection, including crossover, mutation, and selection operations to evolve optimal solutions over successive generations. Research has demonstrated GA's effectiveness in optimizing neural network connection weights and architecture [37] [39].

- Ant Colony Optimization (ACO): Swarm intelligence algorithms inspired by the foraging behavior of ants, which use pheromone trails to collectively find optimal paths through graphs. ACO has been successfully adapted for continuous optimization problems including neural network training, with studies showing it can outperform GA in terms of optimization time and precision for certain applications [39] [38].

These optimization techniques are classified as population-based algorithms, where an initial population is randomly created and iteratively refined to approach optimal solutions [37]. Their ability to explore complex search spaces without relying on gradient information makes them particularly valuable for optimizing non-convex objective functions common in deep learning architectures.

Hybridization Methodologies

The integration of neural networks with nature-inspired optimizers can be implemented through several architectural strategies:

- Weight Optimization: Using ACO or GA to determine optimal connection weights instead of traditional backpropagation, potentially escaping local minima [38].

- Architecture Search: Employing optimization algorithms to identify optimal neural network topologies, including the number of hidden layers and neurons [37].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimizing learning rates, momentum terms, and regularization parameters to enhance network performance [37].

- Hybrid Training: Combining global search capabilities of nature-inspired algorithms with local refinement through gradient-based methods for improved convergence [38].

Applications in Male Infertility Research

Diagnostic and Predictive Modeling

Hybrid AI models have demonstrated remarkable performance across multiple domains of male infertility assessment and prediction:

Table 1: Performance of AI Models in Male Infertility Applications

| Application Area | AI Technique | Performance Metrics | Sample Size | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm Morphology Analysis | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | AUC of 88.59% | 1,400 sperm cells | Automated classification of sperm abnormalities |

| Sperm Motility Assessment | SVM | Accuracy of 89.9% | 2,817 sperm cells | Objective motility tracking and categorization |

| NOA Sperm Retrieval Prediction | Gradient Boosting Trees (GBT) | AUC 0.807, 91% sensitivity | 119 patients | Predicting successful sperm retrieval in NOA patients |

| IVF Success Prediction | Random Forests | AUC 84.23% | 486 patients | Prognosticating ART outcomes for treatment planning |

| Sperm DNA Fragmentation | Deep Neural Networks | Not specified | Not specified | Assessing genetic integrity of spermatozoa |

These applications address critical limitations in traditional male infertility diagnostics by providing quantitative, reproducible assessments of sperm parameters and data-driven prognostic models for clinical decision-making [35]. The surge in research activity since 2021, with 57% of relevant studies (8 of 14) published between 2021-2023, reflects growing recognition of AI's potential in this field [35].

Comparative Performance of Optimization Techniques

Research comparing optimization algorithms for neural network training in biological applications provides insights into their relative strengths:

Table 2: Comparison of Optimization Techniques for Neural Networks

| Optimization Technique | Key Advantages | Limitations | Demonstrated Performance in Biomedical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) | Faster convergence, higher precision in specific domains [39] | Complex parameter tuning | Effective for feed-forward network training on medical pattern classification [38] |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Robust global search capabilities, parallelizable | Computational intensity, premature convergence | Successful in optimizing neural network weights and architecture [37] |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Simple implementation, efficient exploration | Potential for swarm stagnation | Applied to energy management problems with strong performance [37] |

| Backtracking Search Algorithm (BSA) | Effective local and global search balance | Limited track record in medical applications | Comparable results to established techniques in benchmark tests [37] |

| Hybrid ACO-Gradient Descent | Combines global exploration with local refinement | Implementation complexity | Superior performance on benchmark pattern classification problems [38] |

Experimental results demonstrate that ACO-based training algorithms can efficiently train feed-forward neural networks for pattern classification tasks relevant to medical diagnostics, with hybrid approaches showing particular promise [38].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Protocol

Objective: To systematically collect and preprocess male infertility data for hybrid neural network model development.

Materials and Reagents:

- Clinical semen samples from urology outpatient departments

- Computer-Assisted Sperm Analysis (CASA) system for parameter quantification

- DNA fragmentation index (DFI) assessment kits

- Hormonal assay kits (FSH, LH, Testosterone)

- Genetic testing reagents for exome sequencing [36]

Procedure:

- Patient Recruitment and Ethical Considerations

- Recruit eligible male partners from infertility clinics following EAU guideline recommendations [36]

- Obtain informed consent for data collection and analysis

- Collect comprehensive clinical history including fertility duration, prior treatments, and relevant comorbidities

Sample Collection and Initial Analysis

- Perform semen collection following WHO standards after 2-7 days of sexual abstinence

- Conduct basic semen analysis assessing volume, concentration, motility, and morphology

- Aliquot samples for additional specialized testing including DNA fragmentation

Advanced Diagnostic Assessments

- Perform sperm DNA fragmentation testing using appropriate methodology

- Conduct hormonal profiling (FSH, LH, Testosterone) via immunoassay techniques

- Consider genetic testing including exome sequencing for idiopathic cases [36]

Data Digitization and Annotation

- Digitize sperm imagery using high-resolution microscopy

- Annotate sperm morphological characteristics by trained embryologists

- Extract motion parameters from video sequences for motility analysis

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

- Normalize numerical parameters to standard scales (z-score or min-max normalization)

- Handle missing data through appropriate imputation techniques

- Perform feature selection to identify most predictive variables

- Partition data into training, validation, and test sets (typical ratio: 60/20/20)

Hybrid Model Development Protocol

Objective: To develop and validate a hybrid neural network model optimized with ACO/GA for male infertility prediction.

Computational Environment:

- Python with TensorFlow/PyTorch or MATLAB with Deep Learning Toolkit

- High-performance computing resources with GPU acceleration

- Implementation of ACO/GA optimization libraries

Procedure:

- Neural Network Architecture Design

- Define input layer dimensionality based on feature set

- Initialize with 1-3 hidden layers with sigmoid/ReLU activation functions

- Configure output layer with appropriate activation (sigmoid for binary classification, softmax for multi-class)

- Initialize connection weights with random values within specified range [-0.5, 0.5]

Optimization Algorithm Implementation

For ACO Implementation:

- Initialize pheromone matrix with uniform values

- Configure ant population size (typically 20-50 artificial ants)

- Set evaporation rate (Ï = 0.1-0.5) and exploration parameters

- Define solution construction rules based on pheromone trails and heuristic information

For GA Implementation:

- Initialize population of candidate solutions (typically 50-100 individuals)

- Configure selection mechanism (tournament or roulette wheel selection)

- Set crossover rate (typically 0.7-0.9) and mutation rate (typically 0.01-0.05)

- Define fitness function based on classification accuracy or error reduction

Hybrid Training Process

- For each training iteration, employ ACO/GA to explore optimal weights/architectures

- Evaluate candidate solutions using k-fold cross-validation (typically k=4-10)

- Update pheromone matrix (ACO) or population (GA) based on fitness evaluation

- Optionally refine best solutions with gradient descent for local optimization

- Continue until convergence criteria met (max iterations or minimal improvement)

Model Validation and Interpretation

- Assess final model performance on held-out test set

- Generate ROC curves and calculate AUC metrics

- Perform feature importance analysis using permutation importance or SHAP values

- Implement biological plausibility checks per interpretable ML frameworks [40]

Workflow Visualization

Performance Analysis and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Rigorous evaluation of hybrid models requires multiple performance dimensions:

Table 3: Comprehensive Model Evaluation Metrics

| Evaluation Dimension | Specific Metrics | Target Performance Range | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy | AUC-ROC, Balanced Accuracy, F1-Score | AUC >0.80 for clinical utility | Diagnostic reliability and decision support |

| Computational Efficiency | Training time, Inference latency, Memory footprint | Compatible with clinical workflows | Practical deployment considerations |

| Robustness and Generalization | Cross-validation consistency, External validation performance | <10% performance drop on external data | Multicenter applicability |

| Clinical Interpretability | Feature importance scores, Biological plausibility | Alignment with known pathophysiology | Clinician trust and adoption |

The performance benchmark for male infertility applications should reference current state-of-the-art results, including AUC values of 88.59% for sperm morphology classification and 84.23% for IVF success prediction achieved with conventional machine learning approaches [35]. Hybrid models should target 5-10% performance improvements over these baselines to demonstrate clinical value.

Implementation Considerations for Clinical Deployment

Successful translation of hybrid models into clinical practice requires addressing several practical considerations:

- Data Quality and Standardization: Implementing standardized protocols for semen analysis and data collection to minimize center-specific biases [35]