DNA Methylation Heterogeneity in the Tumor Microenvironment: Drivers, Detection, and Clinical Translation

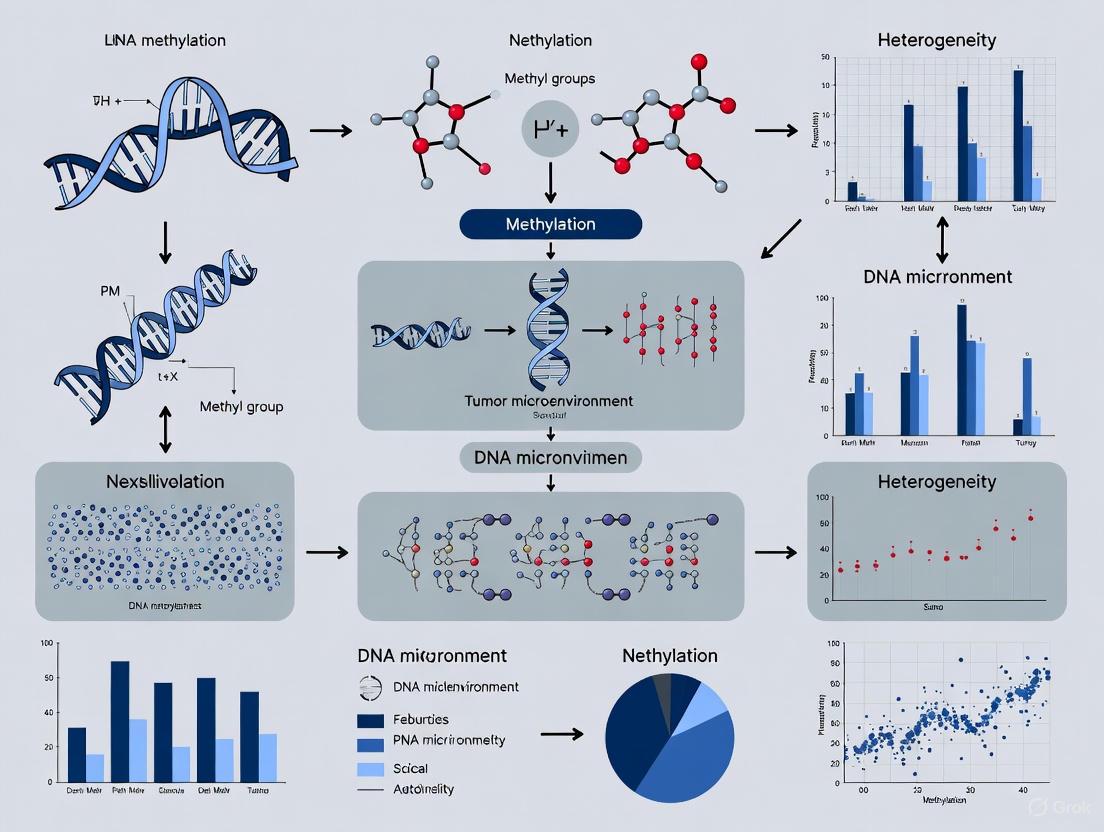

This article comprehensively explores the critical role of DNA methylation heterogeneity (DNAmeH) within the tumor microenvironment (TME), a key driver of tumor progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance. We examine the foundational sources of intratumoral and intertumoral epigenetic variation, from diverse cell compositions to allele-specific methylation. The review details advanced methodologies for quantifying DNAmeH, including bisulfite sequencing, microarrays, and machine learning, and discusses their application in developing predictive biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Furthermore, we address the challenges in data interpretation and clinical integration, presenting optimization strategies and validation frameworks. By synthesizing insights from single-cell analyses to pan-cancer studies, this work provides a roadmap for leveraging DNAmeH to refine cancer diagnostics and develop novel epigenetic therapies, ultimately advancing the field of precision oncology.

DNA Methylation Heterogeneity in the Tumor Microenvironment: Drivers, Detection, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the critical role of DNA methylation heterogeneity (DNAmeH) within the tumor microenvironment (TME), a key driver of tumor progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance. We examine the foundational sources of intratumoral and intertumoral epigenetic variation, from diverse cell compositions to allele-specific methylation. The review details advanced methodologies for quantifying DNAmeH, including bisulfite sequencing, microarrays, and machine learning, and discusses their application in developing predictive biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Furthermore, we address the challenges in data interpretation and clinical integration, presenting optimization strategies and validation frameworks. By synthesizing insights from single-cell analyses to pan-cancer studies, this work provides a roadmap for leveraging DNAmeH to refine cancer diagnostics and develop novel epigenetic therapies, ultimately advancing the field of precision oncology.

Unraveling the Sources and Significance of Epigenetic Diversity in Tumors

The Tumor Microenvironment (TME) represents a complex and dynamic ecosystem that surrounds cancer cells, playing a pivotal role in tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and treatment response. Comprising diverse cellular and non-cellular components, the TME consists of malignant cells, stromal cells, immune cells, blood vessels, extracellular matrix (ECM) components, and soluble factors such as growth factors and cytokines [1]. These components engage in continuous crosstalk, creating a network of interactions that can either suppress or promote tumor development. The TME is not merely a passive bystander but actively contributes to the malignant phenotype by offering a favorable niche for cancer cell survival, proliferation, and dissemination [1]. Understanding the intricate architecture and cellular origins within the TME has become paramount in cancer research, particularly with the growing recognition of its influence on therapeutic resistance and immune evasion mechanisms.

Within the context of modern cancer biology, the TME framework provides essential insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies. The immunosuppressive nature of the TME, mediated through immune checkpoint molecules (like PD-L1/PD-1), cytokines (such as TGF-β and IL-10), and specific immune cells (including regulatory T-cells and tumor-associated macrophages), inhibits effective anti-tumor immune responses [1]. Furthermore, cancer cells within the TME adapt to extreme conditions like hypoxia, acidic pH, and nutrient deprivation, enhancing their resistance to conventional therapies including radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted treatments [1]. This review explores the cellular origins and diverse components of the TME, with particular emphasis on how DNA methylation heterogeneity serves as both a driver and biomarker of this complexity, offering new avenues for diagnostic and therapeutic innovation.

Cellular Composition of the Tumor Microenvironment

Tumor Cells: The Architects of the TME

Cancer cells constitute the fundamental building blocks of tumors and act as primary architects of the TME. Tumor initiation begins when a single cell undergoes genetic or epigenetic alterations that allow it to evade typical growth regulators like apoptosis and senescence [1]. These transformations often result from mutations in tumor suppressor genes (such as TP53 or BRCA1) or oncogenes (like KRAS or EGFR), leading to uncontrolled cell division and survival [1]. As the tumor expands, cancer cells not only proliferate locally but also actively reshape their surrounding environment by releasing signaling molecules that promote immune evasion, angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels), and extracellular matrix remodeling [1].

A critical aspect of tumor biology that significantly impacts therapeutic outcomes is tumor heterogeneity, which exists at two distinct levels:

- Inter-tumor heterogeneity: Refers to variations between tumors from different patients, even within the same cancer type. These differences influence prognosis and therapeutic response, underscoring the necessity for personalized treatment approaches.

- Intra-tumor heterogeneity: Describes the genetic, epigenetic, and phenotypic diversity among cancer cells within a single tumor. This heterogeneity arises through clonal evolution, where subpopulations of cancer cells acquire unique mutations that provide competitive advantages [1].

The interactions between tumor cells and their surrounding TME further amplify this heterogeneity, creating a complex landscape where different cellular subpopulations may exhibit varying responses to the same treatment, ultimately contributing to therapy failure and disease relapse [1].

Stromal Cells: The Supportive Framework

Stromal cells provide essential structural and functional support within the TME, contributing significantly to tumor growth and dissemination.

- Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs): As the most abundant stromal cells in the TME, CAFs influence cancer cell invasion, migration, and treatment resistance by secreting soluble molecules and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins [1]. They represent activated fibroblasts that have been co-opted by cancer cells to support tumorigenic processes.

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): These pluripotent cells are recruited to tumors where they differentiate into various cell types, including CAFs, and secrete growth factors and cytokines that promote tumor growth [1].

- Endothelial Cells: These cells form the lining of blood vessels and play vital roles in angiogenesis, the process of new blood vessel formation that provides essential oxygen and nutrients to growing tumors, enabling their expansion and metastatic spread [1].

Immune Cells: The Dual-Natured Components

The immune compartment within the TME exhibits remarkable complexity and functional ambivalence, capable of either suppressing or promoting tumor progression.

Table 1: Key Immune Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment

| Immune Cell Type | Primary Functions in TME | Pro-tumor Activities | Anti-tumor Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) | ECM remodeling, cytokine secretion | M2 polarization: promotes angiogenesis, immune suppression [1] | M1 polarization: promotes inflammation, anti-tumor immunity [2] |

| Regulatory T-cells (Tregs) | Immune regulation | Suppresses effector immune cells, enables immune evasion [1] | - |

| CD8+ T-cells | Cytotoxic activity | - | Recognizes tumor antigens, releases IFN-γ and granzyme B [2] |

| CD4+ T-cells | Immune cell activation | - | Releases IL-2, IL-4, IL-17 to activate other immune cells [2] |

| Natural Killer (NK) Cells | Immune surveillance | - | Targets tumor cells for destruction, produces IFN-γ [2] |

| Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) | Immune suppression | Inhibits T-cell function, promotes immune tolerance [1] | - |

| Neutrophils | Inflammation, tissue remodeling | Secretes VEGFA and MMP9 to promote angiogenesis and invasion [2] | - |

The dynamic and often immunosuppressive nature of the TME represents a major challenge for cancer therapy. The presence of immunosuppressive cells like Tregs and MDSCs, combined with the expression of immune checkpoint molecules, creates a barrier to effective anti-tumor immunity [1]. Understanding these cellular interactions provides the foundation for developing innovative immunotherapies that can reprogram the TME to favor tumor elimination.

DNA Methylation Heterogeneity as a Central Regulator

Fundamentals of DNA Methylation in Cancer

DNA methylation, specifically 5-Methylcytosine (5mC), represents the most prevalent DNA methylation modification in the human genome, and its abnormal patterns are strongly associated with tumor progression [3]. This epigenetic mechanism involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases in CpG dinucleotides, resulting in altered gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence. In normal cells, approximately 60-80% of CpG sites in the human genome are methylated, maintaining transcriptional stability and cellular identity [4]. However, cancer cells exhibit widespread disruption of DNA methylation patterns, characterized by global hypomethylation (leading to genomic instability) and localized hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters (silencing their expression) [3].

The emergence of DNA methylation heterogeneity (DNAmeH) within tumors represents a crucial aspect of cancer evolution. Intratumoral and intertumoral DNAmeH primarily arises from cancer epigenome heterogeneity and the diverse cell compositions within the TME [3]. While methylation at a single CpG site in an individual cell is typically binary (either fully methylated or unmethylated), bulk tumor tissue analysis often reveals intermediate methylation signals. This intermediate methylation (approximately 2% of the 26.9 million CpG sites in the human genome) reflects the heterogeneous mixture of different cell types within the tumor immune microenvironment [4]. The coexistence of cells with distinct methylation patterns in tumor tissues creates this mosaic of methylation states, serving as a molecular fingerprint of the TME's cellular complexity.

Quantitative Assessment of DNA Methylation Heterogeneity

Advancements in high-throughput sequencing and microarray technologies have facilitated the development of robust quantitative methods for measuring DNAmeH [3]. These approaches enable researchers to dissect the epigenetic landscape of tumors with unprecedented resolution.

Table 2: Methods for Quantifying DNA Methylation Heterogeneity

| Method | Principle | Application in TME Research |

|---|---|---|

| PIM (Proportion of sites with Intermediate Methylation) | Calculates the proportion of CpG sites with β-values between 0.2-0.6 across the genome [4] | Measures intertumoral DNA methylation heterogeneity; higher PIM reflects stronger heterogeneity and immune cell infiltration [4] |

| PDR (Proportion of Discordant Reads) | Captures the methylation status of individual CpG sites in different cells from sequencing data [4] | Analyzes DNA methylation heterogeneity within samples at single-molecule resolution |

| Epiallele Analysis | Identifies and quantifies distinct epigenetic alleles in a cell population [4] | Facilitates analysis of DNA methylation heterogeneity within samples |

| CMHC (Cell-type-associated DNA Methylation Heterogeneity Contribution) | Dissects the effect of different immune cell types on β-values of cell-type-associated heterogeneous CpG sites (CpGct) [4] | Quantifies contribution of specific immune cell types to overall methylation heterogeneity |

| Shannon Entropy-Based Method | Quantifies methylation differences using Shannon entropy to identify cell type-specific methylation sites [2] | Identifies informative methylation sites for deconvolution algorithms; higher entropy indicates more informative sites |

The PIM score, calculated as PIM = numCpGinter/N (where numCpGinter represents the number of CpG sites with β-values from 0.2 to 0.6, and N represents the total number of genome-wide CpG sites for each patient), has emerged as a particularly valuable metric [4]. A higher PIM score indicates greater enrichment of intermediate methylation sites in tumor tissue, reflecting stronger DNA methylation heterogeneity. This measure has demonstrated clinical relevance across various cancer types, including glioma, where enhanced DNA methylation heterogeneity associates with stronger immune cell infiltration, better survival rates, and slower tumor progression [4].

Methodologies for Deconvoluting TME Cellular Composition

Reference-Based Deconvolution Using DNA Methylation Data

Deconvolution algorithms mathematically dissect bulk tumor methylation data into its constituent cellular components by leveraging reference methylation profiles of purified cell types. The fundamental principle assumes that DNA methylation data from tissues represent a convolution of cell type-specific methylation patterns and the proportions of different cell types [2]. The process can be represented as:

Bulk Tissue Methylation = Σ(Cell Type Proportion × Cell Type-Specific Methylation) + Error

The experimental workflow for deconvolution typically involves:

- Reference Database Construction: Collecting DNA methylation profiles of purified immune cells from public repositories like GEO (e.g., GSE35069), encompassing various immune cell types including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD56+ NK cells, CD19+ B cells, CD14+ monocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils [2].

- Feature Selection: Identifying informative CpG sites that show maximal variation between cell types using methods like Shannon entropy-based selection [2].

- Algorithm Application: Employing mathematical deconvolution approaches to estimate cell type proportions in bulk tumor samples using the reference matrix and selected features.

Deconvolution Workflow for TME Cellular Composition

Experimental Protocols for DNA Methylation Analysis in TME Studies

Protocol 1: Pan-Cancer Immune Heterogeneity Analysis Based on DNA Methylation

This protocol outlines the methodology for large-scale analysis of TME composition across multiple cancer types [2]:

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Obtain DNA methylation profiles, gene expression data, and clinical data from TCGA (14 cancer types, 5323 tumor samples).

- Acquire immune cell methylation references from GEO (GSE35069 for 7 immune cell types).

- Map chip probe locations to specific gene sites and average methylation values for identical gene sites.

Cell Type-Specific Methylation Gene Selection:

- Apply Shannon entropy-based method (QDMR software) to identify specific methylation sites.

- Calculate Shannon entropy value (H₀ = -Σps/r log₂ps/r) for each gene site across 7 immune cell types.

- Select top 1256 specific methylation sites based on entropy values for deconvolution input.

Pan-Cancer Tissue Deconvolution:

- Utilize deconvolution algorithm to calculate cell subtype proportions in tissue.

- Apply non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) clustering to identify tumor immune microenvironment subtypes.

- Validate results with phenotypic data (survival, tumor stage) and gene expression correlations.

Protocol 2: Glioma DNA Methylation Heterogeneity and Immune Microenvironment Analysis

This specialized protocol focuses on glioma TME characterization [4]:

Tumor Immune Microenvironment Subtyping:

- Calculate single-sample gene set enrichment scores (ssGSEA) for 34 cell types using R package gsva.

- Perform NMF clustering with k=3-8, repeated 50 times, selecting optimal k based on coupling coefficient.

- Group patients into three tumor immune microenvironmental subtypes (NMF-1, NMF-2, NMF-3).

DNA Methylation Heterogeneity Evaluation:

- Calculate PIM scores using β-value range 0.2-0.6.

- Correlate PIM scores with clinical parameters and survival outcomes.

Cell-type-associated Heterogeneity Analysis:

- Identify cell-type-associated heterogeneous CpG sites (CpGct) for 6 immune cell types.

- Construct CMHC score to quantify immune cell type impact on CpGct β-values.

- Develop Cell-type-associated DNA Methylation Heterogeneity Risk (CMHR) score using 8 prognosis-related CpGct.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of cellular origins and TME components requires carefully selected reagents and methodologies. The following table outlines essential resources for conducting TME DNA methylation studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for TME DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Methylation BeadChip | Genome-wide methylation profiling | HumanMethylation450K or EPIC array covering >850,000 CpG sites [4] [2] |

| DNA Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils for methylation detection | High-efficiency conversion (>99%) with minimal DNA degradation [4] |

| Purified Immune Cell Populations | Reference profiles for deconvolution algorithms | CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD56+ NK cells, CD19+ B cells, CD14+ monocytes, neutrophils from healthy donors [2] |

| QDMR Software | Identifies specific methylation sites using Shannon entropy | Version 1.0; quantifies methylation differences for feature selection [2] |

| Deconvolution Algorithm Package | Mathematical decomposition of bulk tissue methylation | R-based implementation supporting non-negative matrix factorization [4] [2] |

| ssGSEA Software | Calculates single-sample gene set enrichment scores | R package gsva with method = 'ssgsea' for immune cell infiltration estimation [4] |

| 3,5-Dibromopyridine-d3 | 3,5-Dibromopyridine-d3, CAS:1219799-05-9, MF:C5H3Br2N, MW:239.91 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Rufinamide-15N,d2 | Rufinamide-15N,d2 Stable-Labeled Isotope | Rufinamide-15N,d2 internal standard for epilepsy research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Clinical Implications and Translational Applications

The analysis of cellular heterogeneity within the TME through DNA methylation profiling carries significant clinical implications across multiple domains of cancer management. In diagnostic applications, DNA methylation signatures serve as powerful tools for tumor classification and subtyping. For instance, in glioma, the Cell-type-associated DNA Methylation Heterogeneity Risk (CMHR) score demonstrates remarkable predictive performance for IDH status (AUC = 0.96) and glioma histological phenotype (AUC = 0.81) [4]. Such precision in molecular classification exceeds conventional histopathological examination and enables more accurate diagnosis.

In the realm of prognostic assessment, DNA methylation heterogeneity provides valuable insights into disease trajectory. The PIM score, reflecting DNA methylation heterogeneity, shows distinct correlations with patient survival outcomes. Counterintuitively, in glioma patients, enhanced DNA methylation heterogeneity associates with stronger immune cell infiltration, better survival rates, and slower tumor progression [4]. This relationship highlights the complex interplay between tumor epigenetics, immune response, and clinical outcomes, challenging simplistic interpretations of heterogeneity as purely detrimental.

For therapeutic decision-making, TME deconvolution offers guidance for treatment selection and response prediction. The identification of specific immune cell populations within the TME helps identify patients most likely to benefit from immunotherapies, such as those with high cytotoxic T-lymphocyte infiltration [4]. Additionally, DNA methylation alterations of prognosis-related CpGct sites may be associated with responses to specific drug treatments in glioma patients, including Temozolomide, Bevacizumab, and radiation therapy [4]. This emerging approach enables a more personalized treatment strategy based on the unique cellular and molecular composition of each patient's TME.

The potential for therapy resistance monitoring represents another critical application. Tumor heterogeneity, reflected in DNA methylation patterns, contributes significantly to treatment resistance and disease relapse [1]. Different cellular subpopulations within the TME may exhibit varying sensitivities to therapeutic agents, leading to selective pressure and expansion of resistant clones. Longitudinal monitoring of DNA methylation heterogeneity could therefore provide early indicators of emerging resistance, allowing for timely intervention and regimen modification.

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The investigation of cellular origins within the TME through the lens of DNA methylation heterogeneity represents a rapidly advancing frontier in cancer biology. Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas, including the integration of multi-omics approaches that combine DNA methylation data with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of TME dynamics [3]. The development of single-cell methylation sequencing technologies promises to revolutionize this field by enabling direct observation of epigenetic heterogeneity without the limitations of deconvolution algorithms, providing unprecedented resolution of the cellular landscape within tumors [3].

Technical advancements in spatial methylation profiling will further enhance our understanding by preserving the architectural context of cellular interactions within the TME. The translation of methylation-based TME classification into clinically applicable biomarkers requires rigorous validation across diverse patient populations and cancer types [2]. Additionally, the exploration of epigenetic therapies that specifically target the dysregulated methylation patterns in cancer cells and TME components offers promising therapeutic avenues [3]. Such approaches might include demethylating agents that reverse immunosuppressive epigenetic programming or compounds that selectively modulate methylation in specific cellular compartments of the TME.

In conclusion, the cellular origins and diverse components of the TME create a complex ecosystem that significantly influences tumor behavior and treatment response. DNA methylation heterogeneity serves as both a driver and biomarker of this complexity, providing valuable insights into tumor classification, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting. The methodologies for deconvoluting TME composition using DNA methylation data, as detailed in this review, empower researchers and clinicians to dissect this complexity with increasing precision. As these approaches continue to evolve and integrate with other technological advancements, they hold tremendous promise for advancing personalized cancer medicine and improving patient outcomes through more precise diagnostic stratification and targeted therapeutic intervention.

The complex orchestration of oncogenesis involves a dynamic interplay between genetic alterations and epigenetic modifications, creating a sophisticated regulatory network that drives tumor development and progression. DNA methylation heterogeneity (DNAmeH) has emerged as a critical mediator in this cross-talk, serving as a molecular bridge that translates genetic instability into diverse and plastic cellular states within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [3]. This heterogeneity arises from both cancer epigenome heterogeneity and the diverse cell compositions within the TME, forming a complex landscape that influences therapeutic response and clinical outcomes [3]. The convergence of mutational burden, copy number variations (CNVs), and cellular stemness represents a particularly crucial axis in this network, contributing to the adaptive capabilities of tumors and posing significant challenges for effective cancer management. Understanding these interconnected relationships provides valuable insights for developing novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies that can address the dynamic nature of malignant progression.

Theoretical Framework: Mechanisms of Genetic-Epigenetic Integration

Mutational Burden and Epigenetic Consequences

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) represents a key genetic feature that significantly influences epigenetic states. Research across multiple cancer types has demonstrated that elevated TMB correlates with increased DNA methylation heterogeneity, suggesting a coordinated relationship between genetic instability and epigenetic diversity [3]. This relationship may be mediated through several mechanisms, including mutations in genes encoding epigenetic regulators and broader disruptions to chromatin organization. The resulting epigenetic heterogeneity contributes to phenotypic diversity within tumor populations, enhancing their adaptive potential.

In stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), comprehensive bioinformatics analyses have revealed significant associations between cancer cell stemness, gene mutations, and the immune microenvironment [5]. The mutational landscape directly influences the stemness properties of cancer cells, quantified through the mRNA expression-based stemness index (mRNAsi), with higher stemness indices correlating with greater tumor dedifferentiation and more aggressive clinical behavior [5]. This relationship underscores how genetic alterations can establish epigenetic and cellular states that favor tumor progression.

Copy Number Variations as Epigenetic Modulators

Copy number variations (CNVs) serve as another genetic element that significantly impacts epigenetic regulation. CNVs can alter the dosage of genes involved in epigenetic processes, including DNA methyltransferases, demethylases, and chromatin modifiers, thereby creating widespread changes in the epigenomic landscape [3]. Studies have identified CNVs as a significant factor influencing DNAmeH, with specific amplifications or deletions correlating with distinct methylation patterns that contribute to tumor evolution [3].

The functional consequences of CNV-driven epigenetic changes are particularly evident in their effect on cellular stemness. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), CNV patterns contribute to the establishment of distinct molecular subtypes with varying stemness characteristics [6]. These subtypes, designated as CRCS1 and CRCS2, demonstrate differential clinical behaviors, with the CRCS2 subtype associated with lower clinical stage/grading and better prognosis, highlighting the clinical relevance of these genetic-epigenetic interactions [6].

Signaling Pathways Governing Stemness Plasticity

The maintenance and regulation of cancer stemness involve multiple interconnected signaling pathways that respond to both genetic and epigenetic cues. Key developmental pathways, including Notch, WNT, Hedgehog (HH), and Hippo, play crucial roles in governing the stem-like qualities of tumor cells [6]. These pathways integrate signals from the TME and genetic alterations to establish and maintain stem cell states through epigenetic mechanisms.

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Cancer Stemness Regulation

| Pathway | Core Components | Epigenetic Effects | Therapeutic Targeting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notch | Notch receptors, CSL transcription factor | Histone modification, DNA methylation changes | γ-secretase inhibitors (in clinical trials) |

| WNT | β-catenin, TCF/LEF factors | Chromatin remodeling, DNA methylation | PORCN inhibitors, tankyrase inhibitors |

| Hedgehog | Patched, Smoothened, GLI factors | DNA methylation of target genes | Smoothened inhibitors (e.g., vismodegib) |

| Hippo | YAP, TAZ, TEAD factors | Histone acetylation, DNA methylation | YAP/TAZ-TEAD interaction inhibitors |

| mTORC1 | mTOR, Raptor | Metabolic regulation of epigenetics | mTOR inhibitors (e.g., rapalogs) |

Crosstalk between additional pathways, including NF-κB, MAPK, PI3K, and EGFR, further modulates stemness characteristics, creating a complex regulatory network that responds to genetic and environmental cues [6]. This network provides multiple nodes for therapeutic intervention, particularly when combined with inhibitors targeting cancer stem cells (CSCs) and immune agents, as explored in clinical trials such as NCT03548571, NCT02541370, and NCT03739606 [6].

Quantitative Assessment: Measuring Heterogeneity and Its Correlates

Metrics for DNA Methylation Heterogeneity

Advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies have facilitated the development of sophisticated quantitative methods for measuring DNA methylation heterogeneity [3]. These metrics capture different aspects of epigenetic diversity, providing researchers with tools to characterize the epigenetic landscape of tumors comprehensively.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for DNA Methylation Heterogeneity

| Metric | Measurement Focus | Technical Approach | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epipolymorphism | Diversity of methylation patterns | Sequencing read analysis | Measures epiallelic richness in cell population |

| Methylation Entropy | Disorder of methylation states | Information theory application | Quantifies epigenetic instability |

| Fraction of Discordant Read Pairs (FDRP) | CpG-level epiallelic diversity | Read pair analysis | Assesses local methylation heterogeneity |

| Quantitative FDRP (qFDRP) | Magnitude of methylation differences | Quantitative read analysis | Enhanced resolution of heterogeneity |

| Proportion of Discordant Reads (PDR) | Local methylation homogeneity | Single-read methylation state analysis | Measures cell-to-cell consistency |

| Methylation Haplotype Load (MHL) | Conservation of methylated haplotypes | Long-range methylation pattern analysis | Evaluates epigenetic signature stability |

| Local Pairwise Methylation Discordance (LPMD) | CpG pair discordance at fixed distances | Pairwise comparison within reads | Reduces read length bias in heterogeneity assessment |

Computational tools such as Metheor have dramatically improved the efficiency of calculating these heterogeneity measures, reducing execution time by up to 300-fold and memory footprint by up to 60-fold compared to previous implementations [7]. This computational advancement enables large-scale studies of DNA methylation heterogeneity profiles, facilitating the analysis of hundreds of cancer cell lines from resources like the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [7].

Correlates of Methylation Heterogeneity in Cancer

Quantitative analyses across multiple cancer types have revealed consistent relationships between DNA methylation heterogeneity and various molecular and clinical features. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), unsupervised clustering of methylation profiles identified two major groups with distinct characteristics [8]. Group 2 exhibited higher tumor purity and a significantly greater frequency of KRAS mutations compared to Group 1 (90.3% vs. 37.5%, p < 0.0001) [8]. This group also demonstrated worse overall survival outcomes (64.2% vs. 42.5% mortality, p = 0.0046), establishing a clear link between specific methylation patterns, genetic alterations, and clinical prognosis [8].

Similar analyses in stomach adenocarcinoma have revealed that stemness indices significantly correlate with tumor mutation burden and immune microenvironment composition [5]. These relationships enable the construction of prognostic models that integrate genetic and epigenetic features to predict patient outcomes and potential therapeutic responses.

Analytical Methodologies: Experimental and Computational Approaches

DNA Methylation Profiling Techniques

Comprehensive assessment of DNA methylation heterogeneity relies on robust experimental methodologies for generating high-quality methylation data. The Illumina Infinium Methylation EPIC BeadChip platform provides extensive genome-wide coverage of CpG sites, particularly focused on promoter-associated regions and enhancers [9]. This technology enables reproducible quantification of methylation levels across large sample sets, making it suitable for population-level studies in cancer research.

For sequencing-based approaches, bisulfite treatment of DNA followed by next-generation sequencing (bisulfite sequencing) remains the gold standard for basepair-resolution methylation analysis [7]. Both whole-genome bisulfite sequencing and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) approaches provide phased methylation information, capturing the co-occurrence of methylation states on individual DNA molecules, which is essential for heterogeneity quantification [7].

DNA Methylation Analysis Workflow

Computational Deconvolution of Tumor Microenvironment

A critical challenge in tumor epigenomics involves disentangling the contributions of various cellular components within the tumor microenvironment. Hierarchical deconvolution of DNA methylation data has emerged as a powerful method for inferring immune and stromal cell abundances in bulk tumor tissues, leveraging the stability and cell lineage specificity of methylation marks [8]. This approach enables researchers to stratify tumors based on their immune microenvironment composition, identifying distinct subtypes such as hypo-inflamed (immune-deserted), myeloid-enriched, and lymphoid-enriched microenvironments [8].

In pancreatic cancer, this deconvolution approach has revealed three distinct TME subtypes with varying cellular compositions and clinical implications [8]. These computational findings are further supported by gene co-expression modules identified through weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), which show enrichment in immune regulatory and signaling pathways [8].

Stemness Quantification and Subtype Classification

The quantification of cellular stemness represents another critical methodological approach in understanding genetic-epigenetic cross-talk. The mRNA expression-based stemness index (mRNAsi) quantifies stemness using gene expression patterns, with values ranging from 0-1, where values closer to 1 indicate stronger stemness characteristics [5]. This index correlates with tumor dedifferentiation and is reflected in histopathological grades [5].

Genetic-Epigenetic Cross-talk Network

Unsupervised clustering algorithms applied to multi-omics data enable the identification of molecular subtypes with distinct stemness characteristics. In ccRCC, this approach has identified CRCS1 and CRCS2 subtypes, which demonstrate differential clinical behaviors, immune microenvironments, and drug sensitivities [6]. The CRCS2 subtype, associated with better prognosis, exhibits a hypoxic state characterized by suppression and exclusion of immune function, and shows sensitivity to specific therapeutic agents including gefitinib, erlotinib, and saracatinib [6].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Investigation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Category | Specific Product/Resource | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation Arrays | Illumina Infinium Methylation EPIC BeadChip | Genome-wide methylation profiling | 850,000 CpG sites, FFPE compatible |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) | DNA treatment for bisulfite sequencing | High conversion efficiency, DNA protection |

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | Nucleic acid isolation from archived samples | Effective paraffin removal, inhibitor reduction |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Metheor toolkit | Methylation heterogeneity calculation | Ultrafast computation, multiple metrics |

| Data Resources | TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas | Multi-omics reference dataset | Clinical, genomic, epigenomic data integration |

| Stemness Analysis | StemChecker webserver | Stemness signature identification | 26 curated stemness signatures |

| Cell Line Resources | Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | Pre-clinical model systems | Multi-omics data for 928 cell lines |

| Deconvolution Algorithms | CIBERSORT, TIMER, ESTIMATE | TME composition inference | Cell-type abundance estimation |

Clinical Implications and Translational Applications

Prognostic Biomarkers and Patient Stratification

The integration of genetic and epigenetic features has powerful implications for cancer prognosis and patient stratification. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma, the development of a multi-omics prognostic model capturing tumor stemness has demonstrated significant value in predicting patient outcomes [6]. This model performed well in both training and validation cohorts, helping identify patients who may benefit from specific treatments or who are at risk of recurrence and drug resistance [6].

Similarly, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, DNA methylation profiling has identified distinct epigenetic subgroups with significant survival differences [9]. The T2 methylation profile, associated with poorly differentiated morphology and squamous features, demonstrates significantly shorter disease-free survival compared to the T1 profile (p = 0.04) [9]. These profiles also show differential methylation patterns in transcription regulation genes and upregulation of DNA repair and MYC target pathways, providing mechanistic insights into their aggressive behavior [9].

Therapeutic Implications and Biomarker Development

Understanding the cross-talk between genetic and epigenetic factors enables more targeted therapeutic approaches. Cancer stem-like cells represent a particularly important therapeutic target due to their association with therapy resistance, metastatic behavior, and self-renewal capacity [6]. Novel therapeutic targets such as SAA2, which regulates neutrophil and fibroblast infiltration in ccRCC, have been identified through stemness-focused analyses [6].

The stratification of tumors based on their immune microenvironment composition, derived from DNA methylation deconvolution, provides valuable insights for immunotherapy applications [8]. Myeloid-enriched versus lymphoid-enriched microenvironments may respond differently to various immunotherapeutic approaches, enabling more precise treatment matching [8].

The intricate cross-talk between genetic alterations, including mutational burden and CNVs, and epigenetic states manifested through DNA methylation heterogeneity creates a complex regulatory network that fundamentally shapes tumor behavior and therapeutic response. Cellular stemness serves as both a mediator and consequence of these interactions, contributing to the dynamic plasticity observed in cancer progression. Advanced analytical methodologies now enable researchers to quantify these relationships with unprecedented resolution, providing insights that span from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. The continuing refinement of these approaches, coupled with the development of innovative computational tools and experimental techniques, promises to further elucidate these relationships and translate them into improved diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for cancer patients.

The regulation of gene expression is a complex process orchestrated by numerous cis-regulatory elements, among which super-enhancers (SEs) have emerged as master regulators of cell identity and disease pathogenesis. These specialized epigenetic structures function as powerful transcriptional hubs that drive the expression of genes critical for cell fate determination, including those involved in oncogenesis and tumor suppression. Within the tumor microenvironment (TME), the interplay between SE activity and DNA methylation heterogeneity creates a dynamic regulatory landscape that significantly influences tumor evolution, therapeutic resistance, and clinical outcomes. SEs are large clusters of enhancer elements that span several kilobases of genomic DNA and are characterized by their dense enrichment of transcription factors (TFs), coactivators, and specific histone modifications [10] [11]. Unlike typical enhancers, SEs exhibit exceptionally strong transcriptional activation potential and demonstrate high cell-type specificity, making them pivotal regulators of genes that define cellular identity [12] [13]. In cancer, particularly pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the transcriptional programs governed by SEs often become subverted to maintain oncogenic states, while simultaneously, the DNA methylation patterns within these regulatory domains contribute to tumor heterogeneity and adaptation [8] [9]. This review examines the intricate relationship between SE-mediated gene regulation and tumor suppressor mechanisms, with particular emphasis on how DNA methylation heterogeneity within the TME influences these processes and offers new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Molecular Architecture and Mechanisms of Super-Enhancers

Structural Characteristics and Identification

Super-enhancers possess distinct structural features that differentiate them from typical enhancers and underlie their potent transcriptional activity. SEs are exceptionally large genomic regions, typically spanning 8 to 20 kilobases, compared to the 200-300 base pair range of typical enhancers [12] [13]. This extended architecture comprises multiple constituent enhancers that function cooperatively to amplify transcriptional output. SEs are densely enriched with master transcription factors, coactivators (including the Mediator complex, BRD4, and p300), and chromatin regulators that form a concentrated transcriptional apparatus [10] [11]. These regions also exhibit characteristic epigenetic signatures, including high levels of histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) and H3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4me1), which mark actively transcribed enhancers [14] [11].

The identification and validation of SEs rely on integrated genomic approaches, primarily chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) for histone modifications (H3K27ac) and transcriptional coactivators (MED1, BRD4), complemented by assays for chromatin accessibility such as ATAC-seq and DNase-seq [11]. Bioinformatic algorithms like ROSE rank enhancer regions based on ChIP-seq signal intensity and merge adjacent enhancers within a defined distance (typically 12.5 kb) to define SE domains [11] [15]. The substantial differences in the binding density of regulatory factors between SEs and typical enhancers are visually apparent in ChIP-seq profiles, with SEs exhibiting dramatically higher signal peaks [12].

Three-Dimensional Organization and Phase Separation

Beyond linear genomic organization, SEs function within the three-dimensional (3D) architecture of the genome. They are frequently located within topologically associating domains (TADs)—self-interacting genomic regions bounded by CTCF and cohesin complexes that facilitate enhancer-promoter interactions [12] [11]. Approximately 84% of SEs reside within large CTCF-CTCF loops, compared to only 48% of typical enhancers, highlighting their privileged positioning within the 3D genome [13]. This spatial organization enables SEs to engage in long-range chromatin interactions with their target gene promoters, forming specialized transcriptional hubs.

Recent research has revealed that SEs undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), a biophysical process that drives the formation of membraneless condensates enriched with transcriptional machinery [10] [11]. Through the intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of transcription factors and coactivators like BRD4 and MED1, SEs form phase-separated condensates that concentrate RNA polymerase II and other transcriptional components, thereby enabling the bursting transcription of SE-driven genes [11]. This phase separation model explains the remarkable transcriptional amplitude and cooperative behavior of SE components, providing a mechanistic basis for their function as specialized regulatory hubs.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Super-Enhancers Versus Typical Enhancers

| Characteristic | Super-Enhancers | Typical Enhancers |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic size | 8-20 kb | 200-300 bp |

| Transcription factor density | Exceptionally high | Moderate |

| Histone modifications | High H3K27ac, H3K4me1 | Lower H3K27ac, H3K4me1 |

| Sensitivity to perturbation | High | Moderate to low |

| Location in 3D genome | 84% within CTCF loops | 48% within CTCF loops |

| Transcriptional output | Very strong | Moderate |

| Cell type specificity | High | Variable |

Super-Enhancer Dysregulation in Oncogenesis

Mechanisms of Oncogenic SE Activation

The pathological activation of oncogenes through SE reprogramming represents a key mechanism in cancer development. Tumor cells can acquire or form de novo SEs at oncogenic loci through multiple mechanisms, including chromosomal rearrangements, amplification of enhancer regions, and transcription factor dysregulation [16]. In various cancers, somatic mutations and structural variations can create novel SE configurations that drive oncogene expression. For example, in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), chromosomal rearrangements can lead to the formation of novel SEs that activate the TAL1 oncogene, while in other hematological malignancies, translocations may place powerful enhancers near oncogenes like MYC [10] [16].

The dysregulation of transcription factors represents another prevalent mechanism of oncogenic SE activation. Chimeric transcription factors generated through chromosomal translocations, such as TCF3-HLF in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and ETO2-GLIS2 in acute megakaryocytic leukemia, can hijack SE regulatory networks to drive oncogenic transcriptional programs [16]. Similarly, the aberrant expression or mutation of transcriptional coactivators like CREBBP and p300 can disrupt normal enhancer control, leading to the pathological activation of SE-driven oncogenes in lymphomas and other cancers [16].

SE-Driven Oncogenic Networks in Solid Tumors

In solid tumors, SEs play crucial roles in maintaining oncogenic transcriptional circuits that promote tumor growth and survival. SEs have been identified as key regulators of core oncogenic pathways in various cancers, including glioblastoma, breast cancer, and pancreatic cancer [11] [15]. These regulatory hubs often control master transcription factors that in turn regulate broad transcriptional programs essential for maintaining the malignant state.

The SE-mediated transcriptional addiction of cancer cells creates a therapeutic vulnerability that can be exploited through the inhibition of SE-associated coactivators. For instance, BRD4 inhibitors have shown efficacy in disrupting SE-driven oncogene expression in multiple cancer types, highlighting the functional significance of these regulatory elements in maintaining tumorigenesis [11] [16]. Additionally, SEs can drive the expression of non-coding RNAs, including enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), that further reinforce oncogenic transcriptional programs through feedback mechanisms [11].

Diagram 1: Oncogenic SE Activation Pathways

DNA Methylation Heterogeneity in the Tumor Microenvironment

Patterns and Measurement of DNA Methylation Heterogeneity

DNA methylation heterogeneity (DNAmeH) represents a critical dimension of tumor evolution and adaptation within the complex ecosystem of the TME. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), comprehensive methylation profiling has revealed distinct methylation patterns that correlate with histopathological features and clinical outcomes [9]. Studies employing high-resolution methylation arrays have identified two major methylation profiles in PDAC: T1 profiles that resemble normal pancreatic tissue and are associated with well-differentiated histology, and T2 profiles that significantly diverge from normal tissue and correlate with poorly differentiated morphology and squamous features [9]. The T2 methylation profile is associated with shorter disease-free survival, highlighting the clinical significance of epigenetic heterogeneity.

DNAmeH arises from multiple sources, including cancer epigenome heterogeneity and the diverse cellular compositions within the TME [3]. The development of quantitative methods for measuring DNAmeH has enabled more precise characterization of this heterogeneity and its functional implications. Metrics for assessing DNAmeH consider differences across cancer types, among individual cells, and at allele-specific hemimethylation sites [3]. Factors influencing DNAmeH include the cell cycle phase, tumor mutational burden, cellular stemness, copy number variations, tumor subtypes, hypoxia, and tumor purity [3]. In PDAC, unsupervised hierarchical clustering of differentially methylated positions has revealed distinct subgroups with varying tumor purity and KRAS mutation frequency, with higher purity samples exhibiting significantly different methylation profiles and poorer survival outcomes [8].

Functional Consequences of DNA Methylation Heterogeneity

The heterogeneous nature of DNA methylation within tumors has profound functional consequences that impact gene regulatory networks and therapeutic responses. Differential methylation analysis of PDAC samples has identified substantial hypomethylation of transcription regulation genes in aggressive T2 profiles, alongside hypermethylation events that potentially silence tumor suppressor pathways [9]. Gene set enrichment analyses have further demonstrated the upregulation of DNA repair and MYC target genes in T2 samples, indicating that specific methylation patterns are associated with activated oncogenic pathways [9].

The hierarchical deconvolution of DNA methylation data has enabled researchers to profile the immune composition of the TME and uncover distinct patterns of tumor immune microenvironments [8]. In PDAC, this approach has revealed three major TME subtypes: hypo-inflamed (immune-deserted), myeloid-enriched, and lymphoid-enriched (notably T-cell predominant) microenvironments [8]. These immune clusters, supported by co-expression modules identified through weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), reflect the interplay between epigenetic heterogeneity and immune cell infiltration, with significant implications for immunotherapy response and patient stratification.

Table 2: DNA Methylation Heterogeneity Patterns in Pancreatic Cancer

| Methylation Profile | Molecular Features | Histological Correlates | Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Profile | Similar to normal tissue, lower KRAS mutation frequency | Well-differentiated morphology | Better survival outcomes |

| T2 Profile | Divergent from normal tissue, high KRAS mutation frequency | Poorly differentiated, squamous features | Shorter disease-free survival |

| Hypo-inflamed TIME | Immune-deserted methylation pattern | Low immune infiltration | Resistance to immunotherapy |

| Myeloid-enriched TIME | Myeloid cell methylation signature | Abundant myeloid cells | Immunosuppressive environment |

| Lymphoid-enriched TIME | T-cell predominant methylation pattern | High T-cell infiltration | Potential response to immunotherapy |

Interplay Between Super-Enhancers and DNA Methylation

Epigenetic Cross-talk in Gene Regulation

The functional relationship between DNA methylation and SE activity represents a critical interface in cancer gene regulation. SEs typically exhibit low levels of DNA methylation, which maintains chromatin accessibility and facilitates transcription factor binding [15]. However, in cancer, SEs frequently display abnormal DNA methylation patterns that can either repress or overexpress target genes. Hypomethylation at SE sites often accompanies oncogene hyperactivation, while hypermethylation can repress tumor suppressor mechanisms [15]. This dynamic regulation involves complex cross-talk between DNA methyltransferases, transcription factors, and histone modifications that collectively determine SE activity.

Research across multiple cancer types has revealed that the expression of SE-driven RNAs and CpG methylation are both pivotal in cancer progression [15]. Analyses of SE-associated CpG dinucleotides have identified distinct clusters of hypermethylation and hypomethylation that correlate with enhancer RNA activation or deactivation. Specifically, hypermethylation is linked to SE deactivation, while hypomethylation is associated with SE activation, highlighting the epigenetic regulation of SEs in cancer progression [15]. This relationship varies across genomic contexts, as observed in embryonic stem cells and epiblast stem cells, where differences in methylation levels correlate with distinct SE activity patterns, particularly at genes regulating pluripotency states [15].

Impact on Tumor Suppressor Networks

The interplay between SEs and DNA methylation extends to the regulation of tumor suppressor networks within the TME. Aberrant DNA methylation at SEs can lead to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes through either direct hypermethylation of SE elements controlling these genes or through hypomethylation-induced activation of SEs that suppress tumor suppressor pathways [15]. In head and neck squamous cell carcinomas and breast cancer, hypermethylated SEs are associated with reduced expression of genes critical for cellular homeostasis, resulting in the overexpression of oncogenic drivers that enhance tumorigenic traits such as proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis [15].

The integration of SE biology with DNA methylation heterogeneity provides a framework for understanding how tumor cells maintain their identity while adapting to therapeutic pressures. Phylogenetic analyses using multi-sampling datasets have suggested evolutionary trajectories from T1 to T2 methylation profiles that coincide with increasingly aggressive phenotypes and genomic instability [9]. This evolution likely involves the progressive rewiring of SE networks through DNA methylation changes that enable tumor cells to overcome microenvironmental constraints and therapeutic challenges.

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Core Techniques for SE and DNA Methylation Analysis

The investigation of SEs and DNA methylation heterogeneity relies on integrated multi-omics approaches that combine genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic methodologies. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) for histone modifications (H3K27ac, H3K4me1) and transcriptional coactivators (MED1, BRD4) remains the gold standard for SE identification [11]. This technique enables genome-wide mapping of enhancer regions and their classification based on binding density and epigenetic signatures. Complementary approaches include DNase I sequencing (DNase-seq) and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) for assessing chromatin accessibility, as well as chromosome conformation capture techniques (3C, 4C, Hi-C) for characterizing the 3D architecture of SE-promoter interactions [11].

For DNA methylation analysis, genome-wide profiling techniques such as the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing provide comprehensive coverage of methylation patterns across the genome [9]. These approaches enable the identification of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and the quantification of methylation heterogeneity within tumor samples. The deconvolution of bulk methylation data using computational algorithms allows for the inference of cellular composition within the TME, providing insights into the interplay between cancer cells and various stromal and immune components [3] [8].

Integrative Analysis and Functional Validation

Advanced computational methods have been developed to integrate SE and DNA methylation data with transcriptomic profiles, enabling the construction of comprehensive regulatory networks. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) identifies co-regulated gene modules that can be linked to specific SE activities and methylation patterns [8]. Bioinformatics resources such as SEdb and dbSUPER provide curated databases of SEs across multiple cell types and cancers, facilitating comparative analyses and hypothesis generation [11].

Functional validation of SE elements and methylation-sensitive regulatory regions relies heavily on CRISPR-based genome editing approaches. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion or perturbation of individual SE components enables researchers to assess their necessity for target gene expression and oncogenic phenotypes [10]. Similarly, targeted epigenetic editing using CRISPR-dCas9 systems fused to DNA methyltransferases or demethylases allows for precise manipulation of methylation status at specific SE regions to determine causal relationships with gene expression changes [10] [15]. These functional studies are essential for distinguishing driver epigenetic alterations from passenger events in cancer evolution.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

| Research Tool | Category | Primary Application | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27ac ChIP-seq | Epigenomic profiling | SE identification and mapping | Genome-wide mapping of active enhancers |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC | DNA methylation array | Methylation heterogeneity analysis | Comprehensive CpG coverage across functional regions |

| CRISPR-Cas9/dCas9 | Genome editing | Functional validation | Targeted manipulation of SE elements and methylation |

| ATAC-seq | Chromatin accessibility | Open chromatin mapping | Identification of accessible regulatory regions |

| BET inhibitors (JQ1) | Small molecule inhibitors | SE functional disruption | Pharmacological targeting of BRD4-dependent SEs |

| DNMT inhibitors (AZA) | Epigenetic drugs | DNA methylation modulation | Experimental alteration of methylation patterns |

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for SE and DNA Methylation Analysis

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

Targeting SE Components and DNA Methylation

The intricate relationship between SEs and DNA methylation heterogeneity presents multiple therapeutic opportunities for cancer intervention. SE-directed therapies primarily focus on disrupting the transcriptional machinery concentrated at these regulatory hubs. Small molecule inhibitors targeting key SE components, such as BRD4 bromodomain inhibitors (JQ1, I-BET) and cyclin-dependent kinase 7 (CDK7) inhibitors (THZ1), have demonstrated promising preclinical efficacy across diverse cancer types [10] [16]. These agents preferentially impair SE-driven oncogene transcription, exploiting the transcriptional addiction of cancer cells to specific SE-regulated networks. Additionally, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) designed to degrade SE-associated proteins offer an alternative approach for dismantling pathogenic enhancer complexes [10].

DNA methylation-targeting therapies, particularly DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (azacitidine, decitabine), represent another strategic approach for modulating the epigenetic landscape of cancer cells [15]. While traditionally used for myeloid malignancies, their application in solid tumors is being re-evaluated in combination with other agents, including immunotherapies. The potential of combining SE-directed therapies with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors lies in their complementary mechanisms for resetting dysregulated transcriptional programs, potentially reversing oncogenic SE states while reactivating silenced tumor suppressor genes [15].

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the promising therapeutic implications, significant challenges remain in translating SE and DNA methylation research into clinical applications. Achieving cell-type specificity in targeting SE components presents a major hurdle, given the fundamental role of these regulatory elements in normal cellular physiology [10]. The dynamic reorganization of SEs in response to therapeutic pressure also necessitates adaptive treatment strategies and combination approaches. Furthermore, the development of effective delivery systems, particularly for crossing biological barriers like the blood-brain barrier in glioblastoma treatment, requires continued innovation [11].

Future research directions will likely focus on advancing single-cell multi-omics technologies to resolve the heterogeneity of SE activities and DNA methylation patterns at cellular resolution within the TME. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches for predicting functional epigenetic alterations and modeling their impact on gene regulatory networks holds promise for identifying key dependencies and resistance mechanisms [10] [9]. Additionally, the development of more selective epigenetic modulators and improved delivery platforms will be essential for translating these strategies into clinically viable therapies that can effectively target the epigenetic drivers of cancer while minimizing effects on normal tissue function.

The functional impact of super-enhancers on gene regulation extends far beyond typical enhancer activity, positioning these epigenetic regulatory hubs as master coordinators of oncogenic programs and cell identity. When viewed through the lens of DNA methylation heterogeneity within the tumor microenvironment, the interplay between these regulatory layers reveals complex mechanisms of tumor evolution, adaptation, and therapeutic resistance. The integrated investigation of SE biology and DNA methylation patterns provides not only insights into fundamental cancer mechanisms but also unveils new therapeutic vulnerabilities that can be exploited through targeted epigenetic interventions. As research methodologies continue to advance, enabling more precise mapping and manipulation of these regulatory elements, the translation of these findings into clinical applications promises to enhance precision oncology approaches and improve outcomes for cancer patients.

Advanced Technologies for Mapping and Applying Methylation Landscapes

DNA methylation, the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine in CpG dinucleotides, represents a stable epigenetic mark that regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [17]. In oncology, aberrant DNA methylation patterns are now recognized as fundamental drivers of tumorigenesis and play a crucial role in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME) [3]. The TME constitutes a complex ecosystem comprising malignant cells, immune cells, stromal elements, extracellular matrix, and various signaling molecules that collectively influence tumor progression, therapeutic response, and resistance mechanisms [18]. DNA methylation heterogeneity (DNAmeH) within this microenvironment arises from both cancer epigenome heterogeneity and diverse cell compositions, creating distinct methylation patterns that exhibit intratumoral and intertumoral variations [3].

Understanding this epigenetic landscape requires sophisticated detection technologies capable of mapping methylation patterns with precision and scalability. This technical guide examines three cornerstone technological platforms for DNA methylation analysis: bisulfite sequencing, microarray platforms, and emerging third-generation sequencing methods. Each platform offers distinct advantages in resolution, throughput, cost-effectiveness, and applicability to clinical samples, enabling researchers to decipher the complex epigenetic dialogue within the TME and its implications for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic development.

Technology Platforms: Principles and Methodologies

Bisulfite Sequencing Platforms

Bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) operates on a fundamental chemical principle: bisulfite conversion selectively deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils (which are read as thymines during sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [19]. This chemical treatment creates sequence polymorphisms that allow for base-resolution detection of methylation status. Conventional bisulfite sequencing (CBS-seq), despite being considered the gold standard, has historically suffered from significant limitations including severe DNA degradation, incomplete conversion in GC-rich regions, and long treatment durations [19].

Recent methodological advancements have substantially addressed these limitations:

- Ultra-Mild Bisulfite Sequencing (UMBS-seq): This innovative approach utilizes an optimized formulation of ammonium bisulfite with precisely controlled pH to maximize conversion efficiency while minimizing DNA damage. The protocol involves incubation at 55°C for 90 minutes with an alkaline denaturation step and inclusion of DNA protection buffer, resulting in significantly improved DNA preservation, higher library yields, and lower background noise compared to conventional methods [19].

- Targeted Panels: Custom targeted bisulfite sequencing panels (e.g., QIAseq Targeted Methyl Panels) enable focused analysis of specific CpG sites across many samples. This approach offers cost-effectiveness for validating biomarker signatures and analyzing larger sample sets, as demonstrated in ovarian cancer research where a custom panel covering 648 CpG sites provided comparable results to microarray platforms [20].

The bioinformatic analysis of BS-seq data requires specialized tools to account for bisulfite-converted sequences. The BEAT (BS-Seq Epimutation Analysis Toolkit) package implements a Bayesian binomial-beta mixture model that aggregates methylation counts from consecutive cytosines into regions, compensating for low coverage, incomplete conversion, and sequencing errors [21]. This statistical approach calculates posterior methylation probability distributions for robust comparison of DNA methylation between samples.

Microarray Platforms

Methylation microarrays, particularly Illumina's Infinium platforms (EPIC v1/v2), represent the workhorse technology for large-scale epigenome-wide association studies. These arrays utilize probe-based hybridization to quantify methylation levels at predefined genomic loci—850,000 to 930,000 CpG sites depending on the version [20] [17]. The technology relies on bisulfite-converted DNA hybridizing to locus-specific probes attached to beads on the array surface, with differential detection of methylated and unmethylated alleles [17].

The standard analytical workflow for microarray data involves:

- Quality Control: Removal of samples with average detection p-value > 0.05 and probes with detection p-value > 0.01 in any sample [20]

- Normalization: Application of normalization algorithms like functional normalization (preprocessFunnorm in R) to address technical variations [20]

- Filtering: Exclusion of probes affected by common SNPs and cross-reactive probes to enhance data reliability [20]

- Beta Value Calculation: Computation of methylation levels as β = intensitymethylated / (intensitymethylated + intensity_unmethylated + 100), producing values between 0 (completely unmethylated) and 1 (completely methylated) [20]

Microarrays have proven particularly valuable for methylation-based classification of tumor types. In central nervous system tumors, three classifier models—deep learning neural network (NN), k-nearest neighbor (kNN), and random forest (RF)—have been developed using microarray data, demonstrating accuracy above 95% in classifying 91 methylation subclasses [17]. The NN model showed particular robustness in maintaining performance with reduced tumor purity, a common challenge in TME research [17].

Third-Generation Sequencing Platforms

Third-generation sequencing technologies, including Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and nanopore-based sequencing, offer distinctive capabilities for methylation detection without requiring bisulfite conversion. These platforms detect methylation through alternative mechanisms:

- SMRT Sequencing: Identifies DNA modifications including 5mC by monitoring kinetics of DNA polymerase during real-time sequencing

- Nanopore Sequencing: Detects base modifications including methylation through characteristic alterations in electrical current signals as DNA passes through protein nanopores

These bisulfite-free approaches present significant advantages for TME research by completely avoiding DNA fragmentation issues associated with bisulfite treatment, thereby better preserving molecular integrity, especially crucial for low-input samples like cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [19]. While enzymatic methyl-sequencing (EM-seq) represents another bisulfite-free alternative that shows improved performance over conventional BS-seq in metrics like mapping efficiency and GC bias, it faces limitations including enzyme instability, complex workflow, and higher costs compared to bisulfite-based methods [19].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Technical Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Platforms

| Parameter | Bisulfite Sequencing | Methylation Microarrays | Third-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Base-level | Predefined CpG sites (850K-930K) | Base-level (direct detection) |

| Coverage | Genome-wide or targeted | Targeted but comprehensive | Genome-wide |

| Input DNA | Varies by method: UMBS-seq enables low-input (10 pg) [19] | Higher input requirements | Lower input requirements |

| Cost Efficiency | Targeted panels cost-effective for large sample sets [20] | Moderate cost, high throughput | Higher cost, decreasing |

| Throughput | High for targeted panels, lower for WGBS | Very high, parallel processing | Increasing with technological advances |

| DNA Damage | Minimal with UMBS-seq [19] | Moderate (requires bisulfite conversion) | Minimal (no bisulfite conversion) |

| Clinical Utility | Excellent for biomarker validation [20] | Established for tumor classification [17] | Emerging for complex genomic regions |

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Clinical Application Contexts

| Application Context | Optimal Platform | Key Performance Metrics | Considerations for TME Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Classification | Microarrays [17] | Accuracy: >95% for CNS tumors [17] | Robust to tumor purity variations (>50%) [17] |

| Biomarker Discovery | Bisulfite Sequencing [20] [19] | High reproducibility across platforms [20] | Enables analysis of low-input samples (cfDNA) [19] |

| TME Deconvolution | Microarrays [8] | Identifies immune subtypes in PDAC [8] | Reveals hypo-inflamed, myeloid-enriched, lymphoid-enriched TME [8] |

| Methylation Heterogeneity | Single-Cell BS-seq [3] | Quantifies intratumoral epigenetic diversity | Requires specialized statistical methods [3] |

The selection of an appropriate methylation detection platform must align with specific research objectives and sample characteristics. For large-scale biomarker screening studies, microarrays offer an optimal balance of throughput, cost, and coverage [20]. When base-resolution methylation data is required across specific genomic regions, particularly for clinical validation studies, targeted bisulfite sequencing provides superior cost-effectiveness for analyzing larger sample sets [20]. For samples with limited DNA quantity or quality, UMBS-seq demonstrates clear advantages with higher library yields and complexity at input levels as low as 10 pg [19].

Comparative studies have demonstrated strong concordance between bisulfite sequencing and microarray platforms. In ovarian cancer research, methylation profiles generated by bisulfite sequencing showed strong sample-wise correlation with Infinium Methylation Array data, particularly in tissue samples (Spearman correlation), though agreement was slightly reduced in cervical swabs likely due to lower DNA quality [20]. Both platforms preserved diagnostic clustering patterns, supporting bisulfite sequencing as a reliable alternative for larger-scale studies [20].

Experimental Design and Protocols

DNA Extraction and Bisulfite Conversion Protocol

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Tissue Samples: Use Maxwell RSC Tissue DNA Kit (Promega) with proteinase K digestion overnight at 56°C followed by automated purification [20]

- Cervical Swabs/Biological Fluids: Employ QIAamp DNA Mini kit (QIAGEN) with carrier RNA to enhance recovery of low-concentration DNA [20]

- FFPE Samples: Implement QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) with extended deparaffinization and optimized incubation conditions [9]

- DNA Quantification: Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) rather than spectrophotometry for accurate concentration measurement of bisulfite-converted DNA

Bisulfite Conversion Methods:

- Conventional Protocol: EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research) with recommended thermocycling conditions: 98°C for 10 minutes, 64°C for 2.5 hours, followed by desulphonation [20]

- UMBS-seq Protocol: Optimized formulation of 100 μL of 72% ammonium bisulfite and 1 μL of 20 M KOH, incubation at 55°C for 90 minutes with DNA protection buffer [19]

- Quality Assessment: Validate conversion efficiency using unconverted lambda DNA spike-in controls; target non-CpG cytosine conversion rate >99.5% [19]

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing Library Preparation:

- Library Construction: Use QIAseq Targeted Methyl Custom Panel kit (QIAGEN) following manufacturer's instructions with 15-18 PCR cycles [20]

- Quality Control: Assess library concentration with QIAseq Library Quant Assay Kit (QIAGEN) and size distribution with Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent) [20]

- Overamplification Rescue: Implement reconditioning of overamplified libraries using GeneRead DNA Library Prep I Kit (QIAGEN) [20]

- Sequencing: Pool libraries in equimolar concentrations, spike with 1-5% PhiX, and sequence on Illumina MiSeq or similar platforms using 300-cycle kits [20]

Microarray Processing Protocol:

- Bisulfite Conversion: Process 500 ng genomic DNA using EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) [9]

- Array Processing: Perform whole-genome amplification, fragmentation, and hybridization to Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip per manufacturer protocol [9]

- Scanning: Process arrays using iScan or similar systems with standard settings [20]

- Data Extraction: Process raw IDAT files using R/Bioconductor packages (minfi) with background correction and dye bias correction [20]

Data Analysis Workflows

Bisulfite Sequencing Data Analysis:

- Alignment: Map bisulfite-converted reads to reference genome using dedicated aligners (Bismark, BSMAP) with in silico conversion approach

- Methylation Calling: Extract methylation counts at each cytosine position using binomial statistics

- Regional Analysis: Implement BEAT package for detecting regional epimutations using binomial-beta mixture model [21]

- Differential Methylation: Identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) using tools like methylKit or dmrseq with multiple testing correction

Microarray Data Analysis Pipeline:

- Preprocessing: Perform background correction, dye bias adjustment, and functional normalization using minfi package in R [20]

- Quality Filtering: Remove probes with detection p-value > 0.01 in any sample, exclude cross-reactive probes, and filter SNP-affected probes [20]

- Beta Value Calculation: Compute methylation values using the standard beta value formula [20]

- Differential Methylation: Identify DMRs using linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation (limma package) with false discovery rate correction [9]

Applications in Tumor Microenvironment Research

Deciphering TME Heterogeneity in Pancreatic Cancer

DNA methylation profiling has revealed critical insights into the complex heterogeneity of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Through unsupervised clustering of methylation array data, researchers have identified two major PDAC subgroups with distinct molecular and clinical characteristics [8]. Group 1 tumors exhibit methylation profiles more similar to normal pancreatic tissue and are associated with well-differentiated histology, while Group 2 tumors display significantly divergent methylation patterns linked to poorly differentiated morphology, squamous features, and substantially worse prognosis (p = 0.0046 for survival difference) [8]. This methylation-based stratification proved more prognostically powerful than conventional histological assessment.

The application of hierarchical deconvolution algorithms to methylation data has further enabled resolution of the PDAC immune microenvironment into three distinct subtypes: hypo-inflamed (immune-deserted), myeloid-enriched, and lymphoid-enriched (notably T-cell predominant) [8]. This stratification provides a robust framework for patient selection in immunotherapy trials and reveals the profound influence of epigenetic regulation on immune cell recruitment and function within the TME.

Intratumoral Methylation Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution

Multi-region methylation analysis using high-density arrays has uncovered extensive intratumoral methylation heterogeneity (DNAmeH) in PDAC, with important implications for tumor evolution and therapeutic resistance [9]. Phylogenetic reconstruction based on methylation profiles has demonstrated an evolutionary trajectory from well-differentiated T1 methylation patterns to poorly differentiated T2 profiles, coinciding with increasingly aggressive phenotypes and genomic instability [9].

This methylation heterogeneity manifests functionally through distinct gene expression programs. T2 methylation profiles show substantial hypomethylation of transcription regulation genes (FDR q < 0.001) and concomitant upregulation of DNA repair and MYC target pathways (FDR q < 0.001) [9]. These epigenetic-evolving subclones within the TME may represent reservoirs of therapeutic resistance, highlighting the importance of multi-region methylation assessment for comprehensive tumor characterization.

Methylation-Based TME Deconvolution