Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Fertility: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review synthesizes current scientific evidence on the impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on human fertility, addressing a critical concern for researchers and drug development professionals.

Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Fertility: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

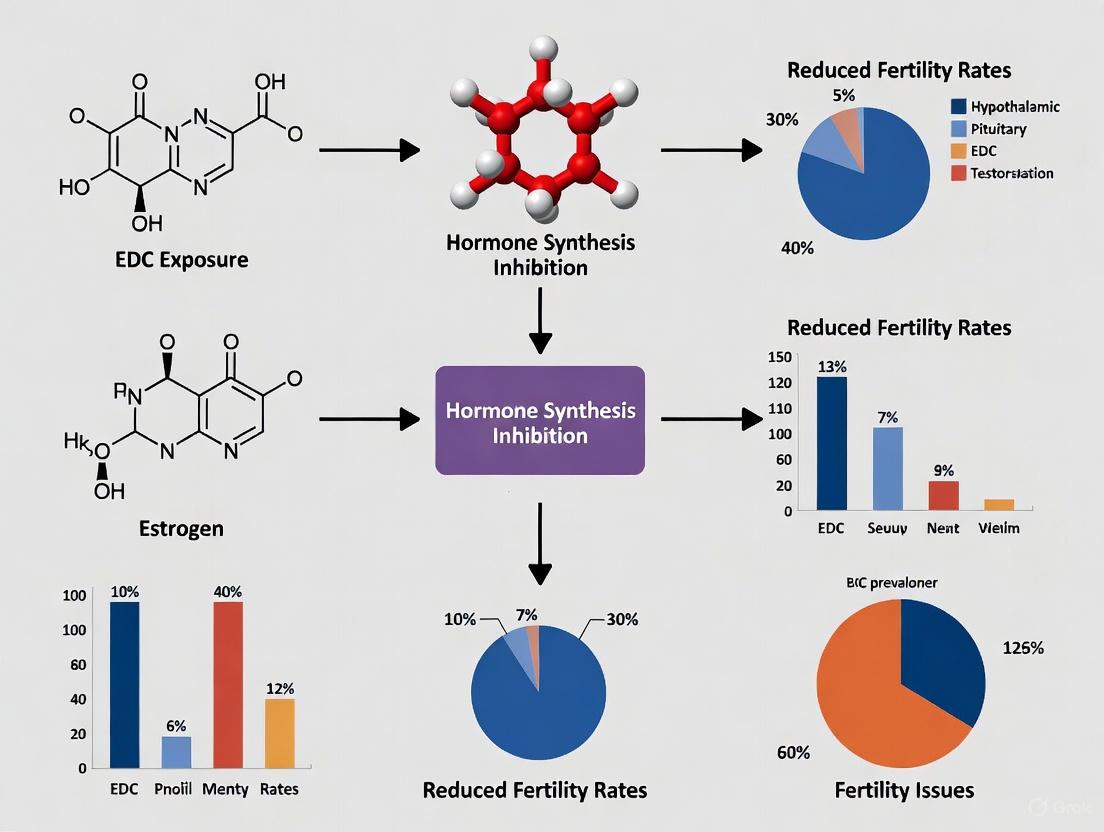

This comprehensive review synthesizes current scientific evidence on the impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on human fertility, addressing a critical concern for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational mechanisms by which EDCs like bisphenols, phthalates, and pesticides disrupt hormonal homeostasis, focusing on receptor-mediated signaling, oxidative stress, and epigenetic modifications. The article evaluates methodological approaches in human epidemiological studies, including challenges in risk assessment such as low-dose effects and chemical mixtures. We further analyze strategies for mitigating EDC exposure and optimizing reproductive outcomes, concluding with a validation of the significant disease burden and economic costs attributable to EDCs, and proposing essential future research avenues for regulatory science and therapeutic development.

Unraveling the Mechanisms: How EDCs Disrupt Reproductive Biology

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are natural or human-made substances that can mimic, block, or interfere with the body's hormones, which are part of the endocrine system [1]. The endocrine system consists of glands distributed throughout the body that produce hormones acting as signaling molecules after release into the circulatory system, controlling biological processes including normal growth, fertility, and reproduction [1]. Hormones act in extremely small amounts, and minor disruptions in their levels may cause significant developmental and biological effects, which is why EDC exposure is a substantial concern for human health, particularly in reproductive and metabolic disorders [1]. This whitepaper details the core concepts of endocrine disruption and focuses on four key chemical classes—Bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, pesticides, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—within the specific context of their impact on fertility research.

Core Concepts of Endocrine Disruption

Endocrine disruption occurs through several molecular mechanisms. EDCs can interfere with hormonal signaling by binding to hormone receptors, acting as agonists or antagonists, and thus activating or inhibiting their activity [2]. They can also alter the expression of hormone receptors in cells, up-regulating or down-regulating their production [2]. A critical mechanism involves affecting co-regulatory proteins that interact with hormone receptors, resulting in changes to receptor function [2]. Furthermore, EDCs can modify signal transduction pathways downstream of the hormone receptor, affecting the cell's response to hormones, and cause epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, which can alter gene expression and hormone receptor function [2]. The delicate balance of the endocrine system, which depends on very small changes in hormone levels, means that even low-dose exposures to EDCs can alter the body's sensitive systems and lead to health problems [1].

Key Chemical Classes

Bisphenol A (BPA) and Analogs

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a synthetic chemical used extensively to manufacture polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, found in food packaging, toys, and the lining of canned foods and beverages [3] [1] [2]. Human exposure occurs when BPA migrates from containers into food and drink, especially upon heating [3]. BPA is classified as an endocrine disruptor due to its xenoestrogenic activity, exerting effects by binding weakly to estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ, activating the membrane receptor GPER, and interacting with estrogen-related receptors [3]. Its structure similarity to estradiol allows it to influence numerous estrogen-related pathways [3].

Due to safety concerns and regulatory restrictions, many BPA analogs—such as bisphenol S (BPS), bisphenol F (BPF), and bisphenol AF (BPAF)—have been introduced as alternatives [2]. However, studies show these analogs can have comparable or even stronger endocrine and toxic effects than BPA, disrupting the endocrine system via interactions with nuclear receptors and related signaling pathways [2]. The order of ERα agonistic activity induced by nine BPA analogs was BPAF > BPB > BPZ > BPA, BPE, BPF > BPS > BPAP > BPP, with BPAF's affinity being about tenfold stronger than BPA's [2].

Table 1: BPA and Analog Health Effects and Research Implications

| Chemical | Key Health Effects on Fertility | Molecular Targets | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Reduced egg quality, oocyte yield, and normal fertilization; increased risk of miscarriage; altered ovarian cycle; linked to hormone-related cancers (breast, ovary, prostate) [3] [4] [5] | ERα, ERβ, GPER, ERRγ [3] [2] | A model EDC for studying mechanisms; requires investigation of low-dose effects and transgenerational inheritance [3] [6]. |

| Bisphenol S (BPS) | Estrogen-like effects; potential for stronger endocrine disruption than BPA via alternative mechanisms (e.g., epigenetic changes) [2] | Estrogen receptors (weaker agonist, potential antagonist) [2] | Key substitute in "BPA-free" products; research should assess full mechanism spectrum, not just receptor affinity [2]. |

| Bisphenol AF (BPAF) | Potent estrogenic activity; acts as ERα/ERβ agonist at some concentrations and antagonist at others [2] | Estrogen receptors (stronger agonist than BPA) [2] | High-potency analog; crucial for studying non-monotonic dose responses and receptor cross-talk [2]. |

Phthalates

Phthalates are a group of synthetic chemicals used primarily as plasticizers to increase the flexibility and durability of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics [7]. They are classified into high molecular weight (HMW) phthalates, such as di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), used in food packaging, medical devices, and building materials, and low molecular weight (LMW) phthalates, such as diethyl phthalate (DEP) and dibutyl phthalate (DBP), used in personal care products like fragrances, lotions, and cosmetics [7]. Exposure occurs mainly through diet from contaminated food and beverages, but also via dermal absorption from cosmetics and inhalation from indoor air and dust [7]. Phthalates interfere with the production of androgens, including testosterone, a hormone critical for male development and relevant to female reproductive health [5]. Their ability to cross the placental barrier makes them a significant concern for maternal and fetal health [7].

Table 2: Phthalate Health Effects and Research Implications

| Chemical / Metabolite | Key Health Effects on Fertility & Metabolism | Molecular Targets | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEHP / MEHP | Decreased oocyte yield, clinical pregnancy rate, and live birth rate in ART; associated with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) [4] [7] | PPARs, androgen synthesis pathways [7] | A key model for studying metabolic disruption; links plasticizer exposure to adverse pregnancy outcomes [7]. |

| MEP (Monoethyl Phthalate) | Decreased fecundability; decreased odds of normal fertilization in ART [4] | Androgen signaling [5] | Common LMW phthalate metabolite; useful non-invasive biomarker for exposure assessment in cohort studies [4] [7]. |

| MBP (Monobutyl Phthalate) | Decreased odds of normal fertilization [4] | Androgen signaling [5] | Like MEP, a key urinary biomarker for correlating exposure with reproductive endpoints in epidemiological studies [4] [7]. |

Pesticides

Pesticides, including insecticides and herbicides, are designed to be toxic to pests' nervous or reproductive systems and often act by disrupting endocrine systems, with effects that can extend to humans and other animals due to similarities in endocrine systems [5]. Exposure occurs through contaminated food, water, air, dust, and soil [4]. Organochlorine pesticides like DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and its metabolite DDE, as well as β-hexachlorocyclohexane (β-HCH) and hexachlorobenzene (HCB), are persistent organic pollutants linked to adverse reproductive effects despite many being banned [4]. Atrazine, a widely used herbicide, has been shown to affect the hypothalamus and pituitary glands [1] [5].

Table 3: Pesticide Health Effects and Research Implications

| Chemical | Key Health Effects on Fertility | Molecular Targets | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDT/DDE | Increased risk of miscarriage, preterm birth, early pregnancy loss; decreased fertilization rate and number of high-quality embryos in ART [4] | Estrogen receptor pathways [5] | A classic, persistent EDC; ideal for studying long-term exposure effects and transgenerational inheritance [4]. |

| β-HCH, HCB | Decreased fecundability; decreased fertilization rate and proportion of high-quality embryos [4] | Estrogen and other steroid hormone signaling pathways [4] | Often co-occur with DDT; research should focus on mixture effects and impacts on oocyte quality and early embryogenesis [4]. |

| Atrazine | Altered puberty, impaired reproductive development [1] [5] | Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis [5] | Model for studying central disruption of the HPG axis and its impact on development and fertility [1] [5]. |

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large group of human-made chemicals containing strong carbon-fluorine bonds, used for their oil- and water-repellent properties in products like nonstick cookware, food packaging, carpets, textiles, and firefighting foam [8] [1] [5]. They are often called "forever chemicals" because they do not break down in the environment and can bioaccumulate in the body and biomagnify through the food chain [8]. Exposure is widespread through contaminated drinking water and diet [8] [9]. PFAS have been linked to a wide range of harmful health effects, including developmental toxicity, liver damage, immune system suppression, endocrine disruption, and kidney or testicular cancer [8]. Their persistence and ubiquitous presence make them a long-term concern for public health.

Table 4: PFAS Health Effects and Research Implications

| Chemical | Key Health Effects | Molecular Targets | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic acid) | Liver damage, endocrine disruption, immune suppression (diminished vaccine response), testicular and kidney cancer [8] | PPARs, lipid metabolism pathways [8] | A legacy PFAS; critical for establishing toxicity pathways and health-based regulatory standards for the entire class [8]. |

| PFOS (Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid) | Similar to PFOA: immune toxicity, endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity, carcinogenicity [8] | PPARs, thyroid hormone transport [8] | Like PFOA, a well-studied legacy compound; research on its mechanisms informs risk assessment for newer analogs [8]. |

| Short-Chain PFAS (e.g., PFBS) | Higher water solubility and mobility; difficult to remove with conventional water treatment [8] | Potential interaction with various cellular receptors [8] | Represent a key technical challenge; research needed on their specific toxicity, bioaccumulation potential, and effective remediation [8]. |

Experimental Methodologies in Fertility Research

In Vitro Assays for Receptor Binding and Transactivation

A foundational approach for identifying potential EDCs involves in vitro assays that assess a chemical's ability to bind to hormone receptors and activate or inhibit transcriptional activity.

- Cell-Based Reporter Gene Assays: These assays use mammalian cells (e.g., human breast cancer MCF-7 cells, BG1Luc cells) engineered to contain a hormone-responsive element (e.g., Estrogen Response Element, ERE) linked to a reporter gene like luciferase [6]. Cells are exposed to the test chemical, and receptor activation is quantified by measuring luminescence. Antagonists can be identified by co-exposing cells to the test chemical and a known agonist (e.g., 17β-estradiol) [6]. This method was pivotal in showing that BPA-free plastic products can leach chemicals with estrogenic activity [6].

- Receptor Binding Assays: These competitive assays use purified hormone receptors (e.g., ERα, ERβ) to measure the displacement of a radio- or fluorescently-labeled natural hormone (e.g., estradiol) by the test chemical. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) provides a measure of binding affinity [2]. This methodology revealed that BPA's affinity for ERα and ERβ is about 10,000-fold lower than that of 17β-estradiol, while BPAF has about a tenfold stronger affinity than BPA [2].

In Vivo and Epidemiological Studies

To translate in vitro findings to health outcomes, particularly in reproduction, more complex study designs are required.

- Animal Models (e.g., Rodent Studies): These studies are crucial for assessing the effects of EDCs on development and fertility. A typical protocol involves exposing mice or rats during critical windows, such as gestation, lactation, or peripubertally [6]. Endpoints measured include age at puberty, ovarian and testicular histology, sperm quality, estrous cyclicity, mating success, and offspring health. For example, perinatal BPA exposure in CD-1 mice was shown to alter body weight and composition in a dose- and sex-specific manner [6].

- Human Biomonitoring and Cohort Studies: These observational studies link internal chemical doses to health outcomes. A standard methodology involves collecting biological samples (e.g., urine, blood, follicular fluid) from a cohort (e.g., couples seeking fertility treatment, pregnant women) and analyzing them for EDCs and their metabolites [4] [7]. Reproductive outcomes (e.g., time to pregnancy, fertilization rate, embryo quality, clinical pregnancy, live birth, miscarriage) are tracked. For instance, studies have correlated urinary levels of phthalate metabolites like MEP and MBP with decreased odds of normal fertilization and clinical pregnancy in women undergoing IVF [4]. A systematic review of such studies found that phthalate levels were significantly present in the urine of patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) [7].

Advanced Models for Mechanistic and Translational Research

- 3D Spheroid Models: Emerging technologies like 3D spheroid models of human liver cells are being used to investigate how pollutants like PFAS contribute to complex diseases in a system that more closely mimics the human organ's architecture and function [9]. These models can be used to study mechanisms of toxicity and test whether effects are reversible [9].

- Exposomics Frameworks: This approach examines the full range of environmental exposures across the life course. The Southern California ShARP Center, for example, uses exposomics to examine how PFAS together with other environmental exposures affect liver disease, collaborating with large consortia to compare data across different communities [9].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Estrogenic Signaling Pathway Disruption by BPA and Analogs

Experimental Workflow for EDC Fertility Risk Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 Cell Line | An estrogen-sensitive human breast adenocarcinoma cell line used in reporter gene assays (e.g., ERE-luciferase) to detect estrogenic/anti-estrogenic activity [6]. | Identifying estrogenic leachates from BPA-free plastics [6]. |

| BG1Luc Cell Line | A human ovarian cell line stably transfected with an estrogen-responsive luciferase reporter, used for high-throughput screening of ER agonists and antagonists. | Quantifying the estrogenic potency of BPA analogs relative to BPA and estradiol [6]. |

| 3D Liver Spheroid Models | Multicellular, three-dimensional structures that mimic human liver architecture and function for studying organ-specific toxicity [9]. | Investigating the mechanisms of PFAS-induced liver disease and testing reversibility [9]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Matrices with known concentrations of EDCs (e.g., in urine, serum) used to calibrate equipment and validate analytical methods for biomonitoring. | Ensuring accuracy and inter-laboratory comparability in human cohort studies measuring phthalate metabolites [7]. |

| Specific Antibodies | For immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western Blot to assess tissue morphology, protein expression, and signaling pathway activation in animal models. | Evaluating the effect of BPA on HOXB9 protein expression in mammary tumor tissue [3]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry for the sensitive and specific quantification of EDCs and their metabolites in complex biological and environmental samples [7]. | Measuring concentrations of multiple phthalate metabolites in urine samples from GDM patients and controls [7]. |

| 4-(Methylthio)quinazoline | 4-(Methylthio)quinazoline|CAS 13182-59-7 | 4-(Methylthio)quinazoline (CAS 13182-59-7) is a versatile quinazoline derivative for pharmaceutical research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| H-Arg-Gly-D-Asp-OH.TFA | H-Arg-Gly-D-Asp-OH.TFA RGD Peptide|For Research | H-Arg-Gly-D-Asp-OH.TFA is an integrin-binding RGD peptide for cell adhesion research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous compounds that interfere with the synthesis, secretion, transport, binding, action, or elimination of natural hormones in the body, thereby disrupting homeostasis and the normal functioning of the endocrine system [10] [11]. The global decline in fertility rates has become a significant public health concern, with substantial evidence pointing to the role of environmental factors, including exposure to EDCs, as a contributing factor [12] [13]. These chemicals can exert their effects at extremely low doses and are particularly damaging during critical developmental windows, such as fetal development, leading to irreversible and even transgenerational effects on reproductive health [14] [11].

EDCs comprise a heterogeneous group of chemicals found in various industrial and consumer products, including plasticizers (e.g., bisphenol A, phthalates), pesticides (e.g., vinclozolin, DDT), heavy metals, and persistent organic pollutants [10] [14] [15]. The molecular pathways through which EDCs disrupt fertility are complex and involve direct interactions with nuclear hormone receptors (genomic pathways) and rapid signaling cascades initiated at the cell membrane (non-genomic pathways). This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these mechanisms, focusing on EDC interactions with estrogen receptors (ERs), androgen receptors (ARs), and thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), which represent critical nodes in the endocrine control of reproduction [16] [17].

Estrogen Receptor (ER) Signaling Disruption

ER Subtypes and Structural Basis for Ligand Recognition

The estrogen signaling pathway is primarily mediated by two nuclear receptors: estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) [17]. These receptors, while binding the endogenous ligand 17β-estradiol (E2) with similar affinity, have distinct tissue distributions and often oppose each other's physiological functions. ERα, encoded by the ESR1 gene on chromosome 6, is a 66 kDa protein consisting of 595 amino acids and is the dominant receptor in the breast, uterus, and liver. ERβ, encoded by the ESR2 gene on chromosome 14, is a 54 kDa protein of approximately 530 amino acids and is prominently expressed in the ovary, prostate, and cardiovascular system [10] [18] [17].

Structurally, both ERs are modular proteins containing:

- An N-terminal domain (A/B domain) housing the ligand-independent activation function-1 (AF-1)

- A central DNA-binding domain (DBD or C domain) with two zinc finger motifs

- A hinge region (D domain) containing a nuclear localization signal

- A C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD or E/F domain) containing the ligand-dependent activation function-2 (AF-2) [18]

The LBD, composed of 12 alpha helices, undergoes significant conformational change upon agonist binding, particularly in the positioning of helix 12, which creates a hydrophobic groove for the recruitment of coactivator proteins with LXXLL motifs [18] [17]. The ligand-binding pockets of ERα and ERβ share high similarity but differ in two key amino acids (Leu384/Met336 and Met421/Ile373 in ERα/ERβ, respectively), which contribute to subtype selectivity for certain ligands [17].

Genomic Signaling Disruption by EDCs

In the classical genomic signaling pathway, E2 binding induces ER dissociation from heat shock proteins (e.g., Hsp90), receptor dimerization, and binding to estrogen response elements (EREs) in the promoter regions of target genes [10] [18]. The consensus ERE is a palindromic 13-base pair sequence (GGTCAnnnTGACC) [17]. The receptor-ligand complex then recruits coregulators and the general transcription machinery to initiate gene transcription.

EDCs such as bisphenol A (BPA), diethylstilbestrol (DES), octyl-phenol (OP), and nonyl-phenol (NP) can mimic natural estrogens by binding to ERs and initiating this transcriptional program [10] [17]. However, their effects are complex and tissue-specific, similar to selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). For instance, BPA acts primarily as an ER agonist in most contexts, while the drug tamoxifen acts as an antagonist in breast tissue but an agonist in the uterus [18]. The transcriptional outcome of ER-EDC interaction depends on several factors, including the specific EDC, ER subtype (ERα vs. ERβ), cellular context, promoter architecture, and available cofactor repertoire [17].

Table 1: Common Estrogenic EDCs and Their Receptor Affinities

| EDC | Primary Source | ERα Activity | ERβ Activity | Relative Potency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diethylstilbestrol (DES) | Pharmaceutical | Agonist | Agonist | High |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Plastics, food containers | Agonist/Weak Antagonist | Agonist/Weak Antagonist | Low (1000-fold lower than E2) |

| Octyl-phenol (OP) | Surfactants, detergents | Agonist | Agonist | Low |

| Nonyl-phenol (NP) | Surfactants, detergents | Agonist | Agonist | Low |

| Genistein (phytoestrogen) | Soy products | Agonist | Preferential Agonist | Low |

Non-Genomic Signaling Disruption by EDCs

Beyond genomic actions, EDCs can rapidly activate signal transduction pathways within minutes through membrane-associated ERs and G-protein coupled receptors (e.g., GPER) [10]. This non-genomic signaling involves the activation of kinases such as ERK1/2 (MAPK), Akt, and protein kinase A (PKA), leading to phosphorylation of transcription factors (e.g., ELK-1, CREB) and other cellular proteins [10] [17]. For example, BPA has been shown to rapidly activate ERK1/2 and Akt in various cell models [10]. These rapid signaling events can ultimately influence transcriptional activity through cross-talk with nuclear ERs, such as via phosphorylation of ERα at key residues (e.g., Ser118, Ser167) by MAPK and Akt, respectively, which enhances its transcriptional activity in a ligand-independent manner [18].

The following diagram illustrates the complex genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways disrupted by estrogenic EDCs:

Androgen Receptor (AR) Signaling Disruption

AR Structure and Signaling Pathway

The androgen receptor is a critical regulator of male reproductive development and function, including spermatogenesis, development of secondary sexual characteristics, and maintenance of sexual behavior [12]. AR belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily and shares a common domain structure with ERs. Upon binding its natural ligands testosterone or dihydrotestosterone (DHT), AR undergoes conformational changes, dissociates from chaperone proteins, dimerizes, and translocates to the nucleus where it binds to androgen response elements (AREs) in target genes to regulate transcription [12] [13].

Mechanisms of AR Disruption by EDCs

EDCs can interfere with AR signaling through multiple mechanisms:

- Receptor Antagonism: Chemicals like vinclozolin (a fungicide) and p,p'-DDE (a DDT metabolite) act as competitive AR antagonists, binding to the receptor but failing to activate it properly, thereby blocking natural androgen action [12] [17].

- Inhibition of Androgen Synthesis: Phthalates such as DEHP and DBP can suppress the expression of genes involved in testosterone biosynthesis, including steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and various cytochrome P450 enzymes [12] [13].

- Altered Metabolic Activation: Some EDCs can interfere with the enzymatic conversion of testosterone to the more potent DHT by inhibiting 5α-reductase [13].

The anti-androgenic effects of EDCs have significant implications for male reproductive health. Population studies have consistently associated EDC exposure with reduced sperm quality, and animal studies provide compelling evidence for transgenerational inheritance of reproductive dysfunction through epigenetic mechanisms [12].

Table 2: Anti-Androgenic EDCs and Their Mechanisms of Action

| EDC | Primary Source | Mechanism of Action | Observed Male Reproductive Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vinclozolin | Fungicide | AR antagonism | Reduced sperm count, hypospadias, transgenerational effects |

| p,p'-DDE | DDT metabolite | AR antagonism | Cryptorchidism, reduced semen quality |

| Phthalates (DEHP, DBP) | Plastics, personal care products | Suppress testosterone synthesis | Reduced anogenital distance, malformations of reproductive tract |

| Procymidone | Fungicide | AR antagonism | Impaired masculinization, retained nipples |

| PBDEs | Flame retardants | Altered steroidogenesis | Reduced sperm count, altered thyroid function |

Thyroid Hormone Receptor (TR) Signaling Disruption

Thyroid Hormone System and Reproductive Health

Thyroid hormones (THs) - thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) - are essential for normal development, metabolism, and reproductive function [15]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis regulates TH production and secretion. In reproduction, thyroid hormones interact with the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, modulating the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and gonadotropins, and directly influencing gonadal function [15].

Molecular Mechanisms of TR Disruption

EDCs can interfere with thyroid hormone signaling at multiple levels:

Receptor-Level Interference: EDCs such as bisphenol A and certain polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) can act as TR antagonists, competing with endogenous T3 for receptor binding [15]. Some EDCs can also bind to TRs and exhibit weak agonist activity.

Disruption of TH Synthesis and Transport: Numerous EDCs affect the sodium/iodide symporter (NIS), thyroperoxidase (TPO), or deiodinase enzymes:

- Perchlorate: Competes with iodide for NIS, reducing iodide uptake and TH synthesis [15].

- Thiocyanates and isoflavones: Inhibit TPO, blocking TH synthesis [15].

- PCBs and PBDEs: Alter TH transport by competing with T4 for binding to transport proteins (transthyretin) and affect TH metabolism by modifying deiodinase activities [15].

The following diagram summarizes the key sites of disruption in the thyroid hormone system by EDCs:

Non-Genomic Signaling Pathways

Characteristics and Significance

Non-genomic signaling refers to rapid, transcription-independent cellular responses to hormones that typically occur within seconds to minutes [10] [17]. These pathways are crucial for understanding EDC actions because:

- They often operate at low EDC concentrations

- They exhibit non-monotonic dose responses

- They can lead to altered cellular responses through cross-talk with genomic pathways [10] [14]

Key Non-Genomic Mechanisms

EDCs can activate various non-genomic signaling pathways:

Calcium and Kinase Signaling: EDCs like BPA and OP can rapidly increase intracellular calcium levels and activate protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades [10].

Cross-Talk with Growth Factor Signaling: Estrogenic EDCs can transactivate epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R), leading to downstream activation of ERK and Akt pathways [10] [18].

G-Protein Coupled Receptor Activation: Several EDCs mediate rapid effects through membrane receptors like GPER, which activates adenylate cyclase and phospholipase C, generating second messengers such as cAMP and IP3 [17].

The rapid activation of these signaling cascades by EDCs can profoundly influence cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, and metabolism, with significant implications for reproductive tissue function and development [10] [17].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

In Vitro Assays for Detecting EDC Activity

A variety of in vitro assays have been developed to identify and characterize EDCs targeting ER, AR, and TR signaling:

Table 3: Key Experimental Assays for EDC Detection and Characterization

| Assay Type | Specific Method | Application | Key Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor Binding Assays | Fluorescence polarization, competitive binding | Measure direct receptor-EDC interaction | Binding affinity (IC50, Ki) |

| Transcriptional Activation Assays | Reporter gene assays (Luciferase, GFP) | Detect agonist/antagonist activity | EC50, IC50, efficacy |

| Cell Proliferation Assays | MCF7 breast cancer cell proliferation (E-SCREEN) | Detect estrogenic activity | Cell number, thymidine incorporation |

| High-Throughput Screening | ToxCast/Tox21 programs | Large-scale EDC screening | Multiple activity profiles |

| Omic Technologies | Transcriptomics, QGexAR models | Predictive modeling of EDC activity | Gene expression signatures [16] |

Detailed Protocol: Transcriptional Reporter Assay for ER Activity

Principle: This assay measures the ability of test chemicals to activate or inhibit estrogen receptor-mediated transcription of a reporter gene (typically luciferase) under the control of an estrogen response element (ERE) [17].

Materials:

- Cell Line: hERα-HeLa-9903 cells (stably transfected with human ERα and ERE-luciferase reporter) [17]

- Controls: 17β-estradiol (E2, 10 nM) as positive control; ICI 182,780 (1 μM) as antagonist control; vehicle (DMSO <0.1%) as negative control

- Test Chemicals: BPA, DES, OP, NP, genistein prepared in DMSO

- Reagents: Luciferase assay kit, cell culture media, phenol-red free DMEM, charcoal-dextran treated FBS

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate hERα-HeLa-9903 cells in 96-well plates at 2×10^4 cells/well in phenol-red free DMEM supplemented with 5% charcoal-dextran treated FBS. Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 hours.

- Chemical Treatment: Treat cells with test chemicals at various concentrations (e.g., 10^-12 to 10^-5 M) in triplicate. Include controls. Incubate for 16-24 hours.

- Luciferase Measurement: Aspirate media, lyse cells with 50 μL passive lysis buffer (Promega) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Transfer 20 μL lysate to white plates, inject 50 μL luciferase assay substrate, and measure luminescence immediately.

- Data Analysis: Normalize luminescence to protein content or cell viability. Calculate fold induction relative to vehicle control. Determine EC50/IC50 values using four-parameter logistic curve fitting.

Validation: The assay should demonstrate a dose-dependent response to E2 with typical EC50 of 0.1-0.3 nM. Antagonists should inhibit E2-induced activity in a dose-dependent manner.

Detailed Protocol: Detection of Non-Genomic ERK Activation

Principle: This protocol detects rapid phosphorylation of ERK1/2 as an indicator of non-genomic signaling activation by EDCs [10].

Materials:

- Cell Line: MCF-7 breast cancer cells or primary granulosa cells

- Antibodies: Anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), anti-total ERK1/2, HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

- Inhibitors: U0126 (MEK inhibitor, 10 μM), ICI 182,780 (ER antagonist, 1 μM)

- Reagents: SDS-PAGE reagents, ECL detection system, serum-free media

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture cells to 70-80% confluence in appropriate media. Serum-starve for 4-6 hours before treatment to reduce basal phosphorylation.

- Chemical Treatment: Treat cells with test EDCs (e.g., BPA, OP) at relevant concentrations for 5-60 minutes. Include E2 (10 nM) as positive control and vehicle as negative control.

- Inhibition Studies: Pre-treat cells with U0126 (30 minutes) or ICI 182,780 (30 minutes) to determine MEK-dependence and ER involvement, respectively.

- Protein Extraction and Western Blot: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Separate 20-30 μg protein by SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membranes, block with 5% BSA, and incubate with primary antibodies (1:1000) overnight at 4°C.

- Detection: Incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Develop with ECL substrate and visualize using chemiluminescence detection system.

- Analysis: Quantify band intensities using densitometry software. Normalize phospho-ERK to total ERK levels. Perform statistical analysis of at least three independent experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Investigating EDC Mechanisms

| Reagent/Cell Line | Supplier Examples | Application in EDC Research |

|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 cells | ATCC (HTB-22) | Model for estrogenic activity; express ERα endogenously |

| MDA-kb2 cells | ATCC (CRL-2713) | Androgen-responsive cell line for anti-androgen screening |

| hERα-HeLa-9903 | NIEHS Chemical Repository | Stably transfected with ERα and ERE-luciferase reporter |

| ERE-Luc Reporter Plasmid | Addgene | For creating custom ER-responsive cell lines |

| Recombinant human ERα/ERβ | Invitrogen, Sino Biological | For direct binding assays (fluorescence polarization) |

| Phospho-ERK1/2 Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology (#9101) | Detection of non-genomic signaling activation |

| Charcoal-dextran treated FBS | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Estrogen-depleted serum for hormone-responsive assays |

| Luciferase Assay Systems | Promega | Reporter gene assays for receptor activity |

| ToxCast/Tox21 Database | EPA/NIEHS | Pre-screened data on thousands of chemicals [16] |

| LINCS L1000 Database | NIH | Transcriptomic profiles of chemical perturbations [16] |

| Befotertinib mesylate | Befotertinib mesylate, CAS:2226167-02-6, MF:C30H36F3N7O5S, MW:663.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1H-Silolo[1,2-a]siline | 1H-Silolo[1,2-a]siline, CAS:918897-39-9, MF:C8H8Si, MW:132.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The molecular pathways through which EDCs disrupt fertility involve complex interactions with nuclear receptors (ER, AR, TR) and activation of non-genomic signaling cascades. Understanding these mechanisms at a detailed level is crucial for developing better risk assessment strategies, identifying susceptible populations, and designing interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of EDCs on human reproduction. The integration of traditional endocrine assays with modern high-throughput screening and computational modeling approaches represents the future of EDC research, enabling more comprehensive assessment of these chemicals and their mixtures on reproductive health across generations.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis is a tiered, linearly organized endocrine system dedicated to the regulation and support of reproductive processes [19]. This axis functions through a precise signaling cascade: a small subset of hypothalamic neurons secretes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which is delivered to the anterior pituitary via the hypophyseal portal circulation [19]. Upon binding to GnRH receptors on pituitary gonadotrope cells, this triggers the synthesis and secretion of the gonadotropins luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) [19]. These gonadotropins then act on the gonads (ovaries or testes) to stimulate steroidogenesis and gametogenesis.

A critical feature of this system is its pulsatile regulation. The precise frequency and amplitude of GnRH pulses are essential for adequate gonadotropin production, with different pulse frequencies preferentially promoting LH or FSH synthesis [19]. This pulsatile activity is highly regulated by kisspeptins, neuropeptides that bind to the GPR54 receptor on GnRH neurons and serve as central processors for relaying peripheral signals [20] [19]. The gonadal steroids (estradiol, progesterone, testosterone) produced in response to LH and FSH then complete the axis by exerting feedback mechanisms on the hypothalamus and pituitary to maintain homeostasis [19]. It is this meticulously balanced system that endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) target, leading to widespread reproductive consequences.

Mechanisms of HPG Axis Disruption by Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals interfere with the normal function of the HPG axis through multiple mechanisms, ultimately leading to hormonal imbalance and impaired fertility. Their actions can be broadly categorized into the following pathways.

Direct Receptor Agonism and Antagonism

Many EDCs structurally mimic natural steroid hormones, allowing them to directly bind to and activate or block hormone receptors.

- Estrogen Receptor (ER) Mediated Signalling: Numerous EDCs, including bisphenol A (BPA), octyl-phenol (OP), nonyl-phenol (NP), and diethylstilbestrol (DES), act as xenoestrogens by binding to estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) with an affinity up to 1000-fold lower than that of endogenous estradiol [10]. This binding can induce tissue-specific oestrogenic responses, acting as either an ER agonist or antagonist, and leading to the dysregulation of ER-dependent transcriptional signalling pathways [10]. The binding of EDCs to nuclear ERs can trigger genomic pathways that alter gene expression over hours, while interaction with membrane ERs can rapidly activate non-genomic pathways, such as ERK1/2 and Akt, within minutes [10].

- Androgen and Progesterone Receptor Interference: EDCs can also bind to and disrupt the function of other steroid hormone receptors, including the androgen receptor (AR) and progesterone receptor (PR) [10]. This interference can block the action of endogenous androgens and progesterone, which are critical for normal reproductive function in both males and females. The disruption of progesterone signalling, for instance, is particularly relevant given progesterone's pivotal role in the growth and development of uterine fibroids [21].

Disruption of Hormone Synthesis and Metabolism

Beyond receptor interactions, EDCs can interfere with the enzymatic pathways responsible for hormone synthesis and clearance.

- Steroidogenic Enzyme Inhibition: EDCs can inhibit key enzymes involved in steroid hormone biosynthesis, such as cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., CYP17A1, aromatase) [22]. For example, reduced aromatase activity would impair the conversion of androgens to estrogens, disrupting the critical balance between these hormones [19].

- Alteration of Hormone Transport and Metabolism: Some EDCs can influence the synthesis of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), affecting the bioavailability of sex steroids [20]. Others may induce liver enzymes that accelerate the metabolic clearance of hormones, effectively reducing their circulating levels [22].

Indirect Effects via the Neuroendocrine System

EDCs can also exert their effects higher up the HPG axis by interfering with central regulatory systems.

- Disruption of GnRH and Kisspeptin Signalling: Exposure to EDCs can alter the expression and release of kisspeptin, a master regulator of GnRH neurons [19] [23]. This disruption can distort the pulsatile secretion of GnRH, which is a prerequisite for normal gonadotropin release. An aberrant GnRH pulse pattern can favour the production of one gonadotropin (e.g., LH) over another (e.g., FSH), leading to conditions like hyperandrogenism, which is often seen in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [20] [19].

- Induction of Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis: EDC exposure can induce cellular stress in reproductive tissues. For instance, BPA and BPF have been shown to induce apoptosis in ovarian granulosa cells via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, compromising follicle health and female fertility [23]. Similarly, oxidative stress in testicular Sertoli and Leydig cells can impair spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis [22].

Table 1: Summary of Key Mechanisms of HPG Axis Disruption by EDCs

| Mechanism of Action | Representative EDCs | Key Molecular/Cellular Effects | Reproductive Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER Agonism/Antagonism | BPA, DES, OP, NP, DDT [10] | Altered ER-dependent transcription; Activation of non-genomic signalling (ERK, Akt) [10] | Altered ovarian function, impaired folliculogenesis, cancer growth [10] [23] |

| AR/PR Antagonism | Phthalates, certain pesticides [10] [22] | Blockade of endogenous androgen/progesterone action [10] | Malefactorize: undermasculinization; Female: uterine disorders [21] [22] |

| Steroidogenic Disruption | Phthalates, cadmium, azole fungicides [22] | Inhibition of CYP enzymes (e.g., aromatase, CYP17A1) [22] | Altered sex steroid ratios (e.g., low E2, high T), anovulation [19] [22] |

| Neuroendocrine Disruption | PCBs, BPA, dioxins [23] [22] | Altered kisspeptin and GnRH pulsatility [19] [23] | Gonadotropin imbalance (e.g., elevated LH:FSH), ovulatory dysfunction [20] [19] |

| Oxidative Stress & Apoptosis | Cadmium, BPA, BPF [23] [22] | Generation of ROS; mitochondrial apoptosis in granulosa/Sertoli cells [23] [22] | Reduced sperm quality; ovarian follicle atresia; decreased fertility [23] [22] |

The figure below provides a simplified overview of the HPG axis and the major sites where EDCs exert their interfering effects.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Investigating EDC Effects

Understanding the impact of EDCs on the HPG axis requires a multi-faceted experimental approach, utilizing everything from in vitro models to human epidemiological studies.

In Vitro Models

In vitro systems are invaluable for elucidating the specific molecular mechanisms of EDC action.

- Cell-Based Reporter Assays: These assays are designed to detect receptor activity (e.g., ER, AR). A common method involves transfecting cells with a plasmid containing an estrogen-response element (ERE) linked to a reporter gene (e.g., luciferase). Exposure to an ER-activating EDC results in receptor binding, transcription of the reporter gene, and a measurable signal (e.g., luminescence), allowing for the quantification of estrogenic potency [10].

- Primary Cell and Tissue Culture Models: Using primary human cells, such as granulosa cells or ovarian cortex tissue explants, provides a more physiologically relevant model. For instance, ovarian cortical tissue culture can be used to assess the direct effects of EDCs on follicle survival and function. The protocol involves obtaining consented human ovarian tissue, dissecting it into small pieces, and culturing them in a specialized medium. Tissues are then exposed to EDCs like BPA or BPF, after which endpoints such as gene expression profiling (e.g., RNA-sequencing), hormone secretion (estradiol), and histology for follicle health are analyzed [24].

- Mechanistic Toxicity Testing: Beyond receptor binding, in vitro models can probe deeper into mechanisms like oxidative stress and apoptosis. For example, to investigate EDC-induced apoptosis in granulosa cells, researchers can treat cells with EDCs and then measure markers like caspase activation, mitochondrial membrane potential (using JC-1 dye), and the ratio of pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins via Western blot [23].

In Vivo Animal Models

Animal studies are crucial for understanding the complex, system-wide consequences of EDC exposure during different developmental windows.

- Immature Rat Uterotrophic Assay: This is a classic, OECD-validated bioassay for detecting estrogenic activity. Immature female rats are ovariectomized to remove endogenous estrogen and allowed to recover. They are then administered the test EDC for 3-5 days. The uterus is subsequently weighed (wet and blotted wet weight). A statistically significant increase in uterine weight in the treated group compared to the control is indicative of estrogenic activity [10].

- Assessment of Pubertal Timing and Ovarian Morphology: To study long-term effects on the HPO axis, perinatal or pubertal animals are exposed to EDCs. Parameters monitored include the day of vaginal opening (a marker of puberty onset), estrous cyclicity via daily vaginal cytology, and terminal analysis of ovarian morphology, looking for signs like polycystic ovaries or reduced follicle counts [20] [23].

- Transgenerational Epigenetic Studies: These experiments involve exposing pregnant females (F0 generation) to EDCs and then studying the offspring (F1) and their subsequent, unexposed generations (F2, F3). Germ cells (sperm or oocytes) and somatic tissues from these generations are analyzed for epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation patterns via bisulfite sequencing, to identify epimutations that may underlie inherited disease susceptibility [22].

Human Cohort Studies and Exposure Assessment

Translating findings from models to human health requires epidemiological studies.

- Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Cohorts: Women and couples undergoing fertility treatments like IVF represent a highly informative cohort. Studies can investigate correlations between internal concentrations of EDCs (measured in urine, blood, or follicular fluid) and ART outcomes such as oocyte yield, fertilization rate, embryo quality, and live birth rates [25] [23]. For example, a study by Guo et al. linked the use of personal care products (a source of EDCs like phthalates and parabens) with lower oocyte maturation rates and a higher risk of miscarriage in women undergoing IVF/ICSI [23].

- Mixture Risk Assessment: Given that humans are exposed to complex mixtures of EDCs, advanced statistical models are employed to assess combined effects. Concentration Addition (CA) and Independent Action (IA) models are two primary predictive frameworks used to estimate the toxicity of chemical mixtures based on data from individual compounds [22].

The workflow for a comprehensive investigation of an EDC's impact on female fertility, integrating these various models, is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating EDC Effects on the HPG Axis

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in EDC Research |

|---|---|

| Immature Rat Model (Uterotrophic Assay) | In vivo bioassay for detecting estrogenic activity of a test compound by measuring increase in uterine weight [10]. |

| Primary Human Granulosa Cells | Used in in vitro cultures to study direct EDC effects on steroidogenesis (e.g., estradiol production), apoptosis, and gene expression relevant to ovarian function [23]. |

| Human Ovarian Cortex Explants | Ex vivo tissue culture model that preserves the ovarian microenvironment, allowing study of EDC effects on early follicle development and survival [24]. |

| Kisspeptin Antibodies | Used for immunohistochemistry or Western blot to localize and quantify kisspeptin expression in hypothalamic tissues after EDC exposure [19]. |

| RNA-sequencing Reagents | For comprehensive, unbiased profiling of transcriptomic changes in tissues (e.g., hypothalamus, pituitary, gonad) or cells after EDC exposure to identify disrupted pathways [24]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Essential for preparing DNA for methylation analysis to investigate EDC-induced epigenetic changes (e.g., in transgenerational studies) [22]. |

| Caspase-3/7 Activity Assay Kit | Fluorometric or luminescent kit to quantify apoptosis activation in cells (e.g., granulosa cells) treated with EDCs like BPA or BPF [23]. |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Gold-standard analytical technique for precise quantification of EDCs (e.g., BPA, phthalate metabolites) and endogenous hormones in biological samples like urine and serum [23] [22]. |

| ER-Specific Reporter Gene Assay | Cell line (e.g., HeLa, MCF-7) engineered with an ERE-luciferase construct to specifically quantify ER agonist/antagonist activity of test chemicals [10]. |

| 1-Isopropylazulene | 1-Isopropylazulene|Research Grade|RUO |

| Malathion beta-Monoacid-d5 | Malathion beta-Monoacid-d5, MF:C8H15O6PS2, MW:307.3 g/mol |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Interventions

The insights gained from research on HPG axis disruption are directly informing the development of novel therapeutic strategies, particularly in the realm of reproductive medicine.

- GnRH Antagonists as a Targeted Therapy: Understanding the central role of GnRH has led to the development and clinical use of oral, non-peptide GnRH antagonists such as elagolix, relugolix, and linzagolix [26] [21]. Unlike GnRH agonists, which cause an initial "flare effect" of increased gonadotropin and estrogen secretion, antagonists competitively block the GnRH receptor, leading to a rapid, dose-dependent suppression of the HPG axis without a flare [26]. These drugs are approved for managing conditions like endometriosis-associated pain and heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids [26] [21].

- The Critical Role of Add-Back Therapy (ABT): The suppression of the HPG axis by GnRH antagonists creates a hypoestrogenic state, leading to side effects such as hot flushes and bone mineral density loss. To mitigate these effects while maintaining therapeutic efficacy, add-back therapy with low-dose estradiol and progestins (e.g., norethindrone acetate) is co-administered [26] [21]. This approach demonstrates a sophisticated application of HPG axis knowledge: achieving a "window" of estrogen suppression sufficient to treat the disease while providing just enough hormone replacement to protect against major side effects, thereby enabling longer-term treatment [26].

- Informing Fertility Treatment Protocols: Research on EDCs that disrupt the HPO axis, such as those found in personal care products, reinforces the need for careful patient history and exposure assessment in clinical fertility practice [23]. Furthermore, the use of hormonal contraceptives to pretreat patients before IVF cycles is a direct application of controlling the HPO axis to synchronize follicular cohorts and time cycles, despite ongoing research into its nuanced effects on outcomes like live birth rates [25].

In conclusion, the systematic interrogation of HPG axis interference by EDCs has not only revealed profound insights into the origins of reproductive diseases but has also catalysed the development of sophisticated, targeted therapeutics. The continued use of integrated experimental models and advanced molecular tools is essential for fully understanding the risks posed by complex EDC mixtures and for designing effective interventions to safeguard and restore reproductive health.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous substances that interfere with hormone action, thereby increasing the risk of adverse health outcomes, including reproductive impairment and infertility [27]. A growing body of evidence links EDC exposure to dysfunctional cellular processes within the reproductive system, primarily oxidative stress, apoptosis, and impaired steroidogenesis [28] [29] [30]. These intertwined molecular pathways form a core mechanistic basis for the adverse fertility outcomes observed in contemporary research. This whitepaper details the specific cellular and molecular consequences of EDC exposure, framing them within the broader context of fertility research for scientists and drug development professionals. It synthesizes current findings, provides structured experimental data, and outlines key methodological approaches for investigating these critical pathways.

Core Cellular Pathologies Induced by EDCs

Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress occurs when the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) overwhelms the capacity of the antioxidant defense system. EDCs can directly promote ROS generation or deplete antioxidant reserves, leading to lipid, protein, and DNA damage [28]. The nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway is a primary cellular defense mechanism against oxidative stress. Under normal conditions, Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by its repressor, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), and targeted for degradation. During oxidative stress, Nrf2 is stabilized, translocates to the nucleus, and activates the transcription of antioxidant genes, including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [28]. EDC-induced disruption of this pathway critically compromises cellular resilience.

Apoptosis

EDCs can trigger programmed cell death, or apoptosis, through both intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor) pathways. This leads to the activation of caspase enzymes, such as caspase-3, which execute the cell death program [28]. In testicular and ovarian tissues, this results in the loss of germ cells and supporting somatic cells (e.g., Leydig and Sertoli cells), directly reducing gamete quality and count, and impairing reproductive function [28] [31] [32].

Impaired Steroidogenesis

Steroidogenesis is the process by which cholesterol is converted into biologically active steroid hormones. EDCs can disrupt the intricate hormonal feedback loops of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and directly inhibit the expression and activity of key steroidogenic enzymes and proteins, such as cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1), 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD17B3), and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) [28] [30]. This leads to insufficient production of sex steroids like testosterone and estradiol, which are essential for reproductive development, function, and fertility [28] [31].

Quantitative Data from Experimental Models

Recent in vivo studies provide quantitative evidence of these cellular consequences and the potential for therapeutic intervention. The following tables summarize key findings from a rat model investigating cisplatin-induced testicular damage and the protective effects of Lisinopril (LSP), which highlighted the involvement of the Nrf2/Keap1/HO-1 and PPARγ signaling pathways [28].

Table 1: Impact of Lisinopril (LSP) on Cisplatin (CDDP)-Induced Hormonal Changes and Oxidative Stress in Rat Testis

| Parameter | CDDP Group vs. Control | LSP + CDDP Group vs. CDDP Group | Effect Size (f) & Statistical Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luteinizing Hormone | Decreased | Effectively Increased | f=2.56, Power=1.00 [28] |

| Follicle-Stimulating Hormone | Decreased | Effectively Increased | f=2.32, Power=1.00 [28] |

| Testosterone | Decreased | Effectively Increased | f=3.02, Power=1.00 [28] |

| Reduced Glutathione | Decreased | Increased Levels | f=1.72, Power=0.99 [28] |

| Superoxide Dismutase | Decreased | Increased Levels | f=1.72, Power=0.99 [28] |

| Malondialdehyde | Increased | Decreased Levels | f=3.07, Power=1.00 [28] |

Table 2: Molecular and Genetic Alterations in Testis Tissue from CDDP and LSP+CDDP Treatment

| Parameter | CDDP Group vs. Control | LSP + CDDP Group vs. CDDP Group | Effect Size (f) & Statistical Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaved Caspase-3 | Increased | Decreased | f=4.61, Power=1.00 [28] |

| Interleukin-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 | Increased | Decreased | f=4.61, Power=1.00 [28] |

| Nuclear Factor Kappa B | Increased | Decreased | f=4.61, Power=1.00 [28] |

| Keap1 Protein | Increased | Reduction in Level | f=5.50, Power=1.00 [28] |

| Nrf2 Protein | Decreased | Increase in Level | f=5.50, Power=1.00 [28] |

| HO-1 Protein | Decreased | Increase in Level | f=3.66, Power=1.00 [28] |

| PPARγ Protein | Decreased | Increase in Level | Reported [28] |

| CYP11a1, HSD17B3, StAR Genes | Downregulated | Upregulated | Reported [28] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following methodology is adapted from a recent study investigating chemoprotective agents against chemotherapy-induced testicular toxicity [28].

Animal Model and Study Design

- Animals: Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (or comparable strain).

- Groups: Rats are randomly assigned into four groups (n=8-10/group):

- Control Group: Receives vehicle only (e.g., saline orally).

- LSP Group: Receives Lisinopril (10 mg/kg) orally for 10 days.

- CDDP Group: Receives a single dose of Cisplatin (e.g., 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally).

- LSP + CDDP Group: Pre-treated with Lisinopril (10 mg/kg orally) for a set period (e.g., 5 days) before receiving a single Cisplatin dose, with Lisinopril treatment continuing for a total of 10 days.

- Sacrifice and Sample Collection: Animals are sacrificed at a predetermined endpoint (e.g., 10 days post-CDPP). Blood is collected for serum hormone profiling, and target tissues (e.g., testes) are rapidly excised. One portion is fixed for histopathology, and another is snap-frozen for biochemical and molecular analyses.

Histopathological Analysis

- Tissue Fixation: Testis samples are fixed in Bouin's solution or 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours.

- Processing and Staining: Tissues are processed through graded alcohols and xylene, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5μm thickness, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

- Evaluation: Slides are examined under a light microscope by a pathologist blinded to the treatment groups. The Johnsen's biopsy score count or a similar scoring system can be used to semiquantitatively assess spermatogenesis. A minimum of 100 tubular cross-sections per animal are scored [28].

Biochemical Assays

- Oxidative Stress Markers:

- Lipid Peroxidation: Measured as malondialdehyde (MDA) content using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) method.

- Antioxidant Enzymes: Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity is assessed via spectrophotometric methods. Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels are determined using Ellman's reagent [28].

- Hormone Assays: Serum levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and testosterone are quantified using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits.

Molecular Analyses

- RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR): Total RNA is isolated from frozen tissue using TRIzol reagent. cDNA is synthesized, and the expression levels of target genes (e.g., CYP11a1, HSD17B3, StAR) are quantified using SYBR Green chemistry, with normalization to housekeeping genes (e.g., Gapdh, Actb).

- Protein Extraction and Western Blotting: Proteins are extracted using RIPA buffer. Equal amounts of protein are separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with specific primary antibodies against targets of interest (e.g., Nrf2, Keap1, HO-1, PPARγ, cleaved caspase-3). Protein bands are visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence and quantified by densitometry.

Signaling Pathways

The protective effects against EDC or toxicant-induced damage often involve the modulation of specific cytoprotective signaling pathways, notably the Nrf2/Keap1/HO-1 axis and PPARγ signaling.

Nrf2 and PPARγ Signaling Pathways: This diagram illustrates the cytoprotective Nrf2/Keap1/HO-1 pathway and the anti-inflammatory PPARγ pathway, which are often impaired by EDCs and can be targeted for therapeutic intervention.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating EDC-Induced Cellular Consequences

| Reagent / Assay | Primary Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin (CDDP) | Chemotherapeutic agent; induces DNA damage, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. | Used in vivo and in vitro to model EDC-like damage, particularly in testicular and ovarian toxicity studies [28]. |

| Lisinopril (LSP) | Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor; investigational protective agent. | Used to investigate mitigation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis via modulation of Nrf2/HO-1 and PPARγ pathways [28]. |

| ELISA Kits | Quantify protein concentrations (hormones, cytokines) in serum and tissue homogenates. | Measure testosterone, LH, FSH, and inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 [28]. |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Quantify mRNA expression levels of target genes. | Assess expression of steroidogenic genes (StAR, CYP11a1, HSD17B3) and inflammatory markers [28]. |

| Western Blot Antibodies | Detect and quantify specific proteins and post-translational modifications. | Analyze protein levels of Nrf2, Keap1, HO-1, PPARγ, and cleaved caspase-3 [28]. |

| SOD & GSH Assay Kits | Spectrophotometric measurement of antioxidant enzyme activity. | Evaluate the status of the cellular antioxidant defense system in tissue samples [28]. |

| MDA (TBARS) Assay Kit | Measures lipid peroxidation as a marker of oxidative stress. | Quantify malondialdehyde levels to assess oxidative damage to cell membranes [28]. |

| Histopathology Stains (H&E) | Visualize tissue architecture and cellular morphology. | Score spermatogenesis and identify histopathological aberrations in gonadal tissues [28]. |

| Tobramycin A | Tobramycin A, MF:C12H25N3O7, MW:323.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (E)-5-Decen-1-yne | (E)-5-Decen-1-yne|CAS 53963-07-8|C10H16 | (E)-5-Decen-1-yne (CAS 53963-07-8) is a high-purity, C10H16 alkenyne for pheromone and organic synthesis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The mechanistic link between EDC exposure and impaired fertility is robustly underpinned by the induction of oxidative stress, apoptosis, and dysregulation of steroidogenesis. Advanced experimental models continue to elucidate the complex signaling networks, such as Nrf2/Keap1/HO-1 and PPARγ, that are compromised by these chemicals. The quantitative data and detailed methodologies outlined herein provide a framework for researchers to further investigate these pathways, identify novel biomarkers, and develop targeted therapeutic strategies to mitigate the detrimental effects of EDCs on reproductive health.

This whitepaper synthesizes current scientific understanding of how epigenetic modifications facilitate transgenerational inheritance, with specific focus on implications for endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) research in fertility studies. Mounting evidence demonstrates that environmental exposures can induce epigenetic changes that persist across multiple generations, potentially contributing to the declining fertility rates observed globally. This technical review comprehensively examines molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and key findings that establish the conceptual framework for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, providing researchers and drug development professionals with critical insights for advancing this evolving field.

Epigenetics represents the study of mitotically and/or meiotically heritable changes in gene function that cannot be explained by changes in DNA sequence [33]. These mechanisms enable the transmission of environmental information across generations through non-genetic pathways, creating a potential biological substrate for the inheritance of acquired traits. The fundamental epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and regulation by non-coding RNAs, all of which alter chromatin structure and accessibility without changing the underlying DNA sequence [33] [34].

Within the context of endocrine disruption research, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI) has emerged as a critical area of investigation. TEI occurs when environmental factors induce epigenetic marks that persist beyond the generation directly exposed, potentially affecting the health and fertility of subsequent generations [35] [36]. For EDCs, this phenomenon raises significant concerns as exposure to these chemicals during sensitive developmental windows may program physiological responses that manifest as reproductive impairments in future generations [37] [38]. The growing body of evidence linking EDC exposure to transgenerational reproductive effects underscores the urgent need to understand the precise molecular mechanisms involved and their implications for human fertility and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Epigenetic Inheritance

DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation

DNA methylation, involving the addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases primarily at CpG sites, represents one of the most extensively characterized epigenetic modifications. This process is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and typically results in transcriptional repression when occurring in promoter regions [33]. During germline reprogramming, most DNA methylation marks are erased, but some resistant loci escape this erasure, potentially enabling transgenerational inheritance [35] [36]. The conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine by TET enzymes serves as an intermediate in DNA demethylation but may also function as an epigenetic mark with distinct regulatory functions [33].

Recent evidence suggests that EDCs can disrupt normal DNA methylation patterns in gametes and reproductive tissues. For instance, exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) has been shown to alter DNA methylation patterns in genes involved in hormonal signaling, potentially contributing to reproductive abnormalities that persist across generations [37] [39]. Similarly, phthalate exposure has been associated with differential methylation in genes regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, providing a plausible mechanism for their transgenerational effects on fertility [30] [40].

Histone Modifications

Histone proteins undergo numerous post-translational modifications that influence chromatin architecture and gene expression. These include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and newer modifications such as lactylation [33]. Specific histone modifications establish chromatin states that either facilitate or repress transcription; for example, histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation (H3K9me3) and H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) are generally associated with transcriptional repression [35] [41].

The transmission of histone modifications across generations represents a more complex mechanism of epigenetic inheritance, as histones are largely replaced during gametogenesis. However, certain histone variants and their associated modifications can escape this reprogramming. Research has demonstrated that H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K27me3 can be transmitted transgenerationally in various model organisms, potentially mediating the inheritance of EDC-induced phenotypic effects [41]. In Drosophila, stable Polycomb-dependent transgenerational inheritance of chromatin states has been documented, with H3K27me3 playing a central role in maintaining these epigenetic states across generations [41].

Non-Coding RNAs

Multiple classes of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs), participate in epigenetic regulation and have been implicated in transgenerational inheritance [36] [34]. These RNA species can guide DNA methylation and histone modifications to specific genomic loci, establishing and maintaining epigenetic states across cell divisions and generations.

In the context of EDC exposure, studies have shown that sperm ncRNAs can carry information about parental environmental exposures to offspring. For example, in mouse models of early life stress, alterations in sperm miRNA profiles were associated with behavioral and metabolic changes in subsequent generations [35]. Similarly, exposure to EDCs such as vinclozolin has been shown to alter the expression of ncRNAs in sperm, potentially contributing to the transgenerational inheritance of reproductive abnormalities [41]. The RNA interference pathway has been demonstrated to be essential for TEI in several organisms, including C. elegans and plants [36].

Table 1: Primary Molecular Mechanisms of Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance

| Mechanism | Molecular Players | Function in TEI | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | DNMT1, DNMT3A/B, TET enzymes, MBD proteins | Stable gene silencing; some marks escape reprogramming | Strong in plants and mammals |

| Histone Modifications | Histone methyltransferases, demethylases, acetyltransferases, deacetylases | Chromatin state memory; certain modifications resist erasure | Strong in fungi, plants, invertebrates; emerging in mammals |

| Non-Coding RNAs | siRNAs, piRNAs, miRNAs, ncRNAs | Guide chromatin modifications; direct epigenetic regulation | Strong in plants, C. elegans; emerging in mammals |

| Prion-like Proteins | Prion proteins, structural templating factors | Self-templating protein conformations | Limited to specific model systems |

Integrated Epigenetic Regulation

These epigenetic mechanisms do not function in isolation but rather form a complex, integrated regulatory network. Cross-talk between DNA methylation and histone modifications has been well-documented; for instance, DNA methylation can recruit proteins that promote specific histone modifications, and vice versa [33]. Additionally, ncRNAs can guide both DNA methylation and histone modifications to specific genomic loci, establishing self-reinforcing epigenetic loops that can persist across generations [36] [41].

Recent research has revealed that EDCs can disrupt this integrated epigenetic network, potentially leading to cascading effects on gene expression and phenotype. For example, studies have shown that exposure to a mixture of EDCs can simultaneously alter DNA methylation patterns, histone modification profiles, and ncRNA expression in reproductive tissues, resulting in transgenerational inheritance of reproductive abnormalities [41]. This integrated perspective is essential for understanding the full scope of EDC effects on epigenetic programming and inheritance.

Diagram 1: EDC-Induced Epigenetic Transgenerational Inheritance Pathways. This diagram illustrates the sequential processes through which endocrine-disrupting chemicals establish epigenetic marks that can be transmitted across generations, ultimately resulting in impaired fertility and other health consequences.

Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Reproductive Health

EDC Exposure and Female Reproductive Health

The pervasive presence of EDCs in the environment raises significant concerns for reproductive health, particularly due to their potential to induce epigenetic changes that may persist across generations [30] [38]. Epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated associations between EDC exposure and various female reproductive disorders, including diminished ovarian reserve, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, and premature ovarian insufficiency [30] [38] [40]. These associations are supported by experimental evidence from animal models showing that developmental exposure to EDCs can reprogram the female reproductive system, leading to impaired fertility in adulthood and subsequent generations.

Specific EDCs have been particularly well-studied for their effects on female reproduction. Bisphenol A (BPA), a component of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, has been shown to interfere with estrogen signaling and alter the development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis [30] [37]. Women with higher urinary BPA levels demonstrate decreased ovarian reserve, lower antral follicle counts, and increased incidence of PCOS and implantation failure [30]. Similarly, phthalates, used as plasticizers in numerous consumer products, have been associated with reduced serum inhibin B levels and advanced-stage endometriosis [30] [40]. These chemicals appear to exert their effects through multiple mechanisms, including epigenetic reprogramming of genes involved in hormonal signaling and folliculogenesis.

EDC Exposure and Male Reproductive Health

Male reproductive health has also been significantly impacted by EDC exposure, with compelling evidence linking prenatal and adult exposure to impaired spermatogenesis, reduced semen quality, and altered testosterone production [39] [40]. The increasing incidence of these abnormalities over recent decades correlates with the rise in production and environmental dissemination of industrial chemicals, suggesting a potential causal relationship [37] [40].

Numerous studies have documented the specific effects of various EDCs on male reproduction. Phthalates have been associated with reduced sperm count and motility, while BPA exposure has been linked to decreased sperm quality and DNA damage [40]. Persistent organic pollutants, including dioxins and organochlorine pesticides, have also been implicated in male reproductive impairments, potentially through epigenetic mechanisms that become apparent across generations [37] [40]. These findings are particularly concerning given the transgenerational nature of some EDC effects, with exposure in one generation potentially affecting the reproductive health of subsequent, unexposed generations.

Table 2: Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Documented Reproductive Effects

| EDC Class | Common Sources | Documented Reproductive Effects | Epigenetic Mechanisms Implicated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenols (BPA, BPS, BPF) | Plastics, food containers, receipts | Reduced ovarian reserve, PCOS, impaired spermatogenesis, implantation failure | DNA methylation changes in hormone response genes, histone modifications in reproductive tissues |

| Phthalates (DEHP, DBP, BBP) | Plastics, personal care products, medical devices | Endometriosis, reduced sperm quality, altered ovarian function, hormonal imbalances | Altered DNA methylation in HPG axis genes, ncRNA expression changes |

| Perfluorinated Compounds (PFAS) | Non-stick coatings, stain-resistant fabrics | Reduced fertility, menstrual irregularities, preeclampsia, testicular cancer | DNA methylation changes in imprinted genes, histone modifications |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants (PCBs, DDT) | Pesticides, industrial processes | Early puberty, reduced semen quality, ovarian dysfunction, endometriosis | Global hypomethylation, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance |

| Parabens | Cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, food preservatives | Reduced testosterone, sperm DNA damage, altered ovarian steroidogenesis | DNA methylation changes in steroidogenic genes |

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

Animal Models of Transgenerational Inheritance

Animal models have been instrumental in establishing causal relationships between EDC exposure and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of reproductive phenotypes. Studies in rodents have provided particularly compelling evidence, with exposure to EDCs such as vinclozolin, methoxychlor, and plastic mixtures resulting in reproductive abnormalities that persist across multiple generations [36] [41]. These models allow for precise control of exposure timing, dose, and duration, enabling researchers to identify critical windows of susceptibility and dose-response relationships.

The standard experimental design for transgenerational inheritance studies involves exposing gestating females (F0 generation) to the EDC of interest during the period of gonadal sex determination in the fetus (F1 generation). The germ cells that will give rise to the F2 generation are also directly exposed during this critical developmental window. True transgenerational effects are observed in the F3 generation and beyond, which were never directly exposed to the EDC [35] [34]. This rigorous experimental approach helps distinguish between direct exposure effects and truly heritable epigenetic changes.

Other model organisms, including C. elegans, Drosophila, and zebrafish, have also contributed significantly to our understanding of TEI. These models offer advantages such as short generation times, genetic tractability, and well-characterized development, facilitating detailed mechanistic studies. Research in C. elegans has been particularly informative regarding the role of small RNAs in TEI, demonstrating that RNAi pathways can transmit environmental information across multiple generations [36] [41].

Epigenomic Profiling Techniques

Advanced molecular techniques have enabled comprehensive mapping of epigenetic modifications across the genome in response to EDC exposure. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing allows for base-resolution mapping of DNA methylation patterns, while ChIP-seq facilitates genome-wide profiling of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites [41]. Additionally, RNA-seq provides a comprehensive view of transcriptome changes, including altered expression of ncRNAs.

These techniques have revealed that EDC exposure can induce widespread changes in the epigenome, with specific patterns associated with particular reproductive phenotypes. For example, studies in animal models exposed to vinclozolin have identified specific genomic regions with altered DNA methylation patterns that are transmitted across generations and associated with reproductive abnormalities [41]. Similarly, research on BPA exposure has revealed effects on histone modification patterns at genes involved in hormonal signaling and reproductive development [37] [39].