Gene Editing for Reproductive Genetic Abnormalities: From CRISPR Foundations to Clinical Translation

This comprehensive review examines the rapidly evolving landscape of gene editing technologies for correcting reproductive genetic abnormalities.

Gene Editing for Reproductive Genetic Abnormalities: From CRISPR Foundations to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the rapidly evolving landscape of gene editing technologies for correcting reproductive genetic abnormalities. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of germline editing, compares emerging CRISPR platforms like base and prime editing against traditional methods, and details rigorous efficiency assessment techniques. The article critically analyzes current ethical frameworks and safety challenges, including off-target effects and mosaicism, while highlighting promising preclinical applications in conditions like male infertility and monogenic disorders. By synthesizing validation strategies and future directions, this resource provides a scientific roadmap for translating gene editing into safe, effective reproductive therapies.

The Scientific and Ethical Foundation of Germline Gene Editing

{c1::Introduction} The {c1::clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)} and {c1::CRISPR-associated (Cas)} system originated as an adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea, providing resistance to invading viruses and plasmids [1] [2]. The simplicity of the type II CRISPR-Cas9 system, which relies on a single Cas protein for DNA cleavage, facilitated its adaptation into a versatile genome-editing tool [2]. This technology has revolutionized genetic research and holds transformative potential for correcting reproductive genetic abnormalities, enabling precise modifications in germline and embryonic cells to prevent the inheritance of debilitating monogenic diseases [3] [4].

{c1::From Bacterial Immunity to Genome Engineering} In its native form, the bacterial CRISPR-Cas9 immune system operates through three key stages to destroy invading nucleic acids [5] [2]:

- Adaptation: Invading viral or plasmid DNA is processed into short fragments called protospacers and integrated into the host's CRISPR locus as new "spacers" between repeat sequences, creating a genetic memory of past infections [2].

- crRNA Biogenesis: The CRISPR locus is transcribed and processed into short, mature CRISPR RNA (crRNA) molecules, each containing a sequence complementary to a previously encountered foreign DNA [1] [5].

- Interference: The mature crRNA, complexed with the Cas9 nuclease and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), guides Cas9 to complementary DNA sequences. Cas9 then introduces a double-strand break (DSB) in the target DNA, provided it is adjacent to a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [2].

The system was engineered for genome editing by fusing the crRNA and tracrRNA into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [1] [5]. To edit a specific genomic locus, scientists simply design an sgRNA with a 20-nucleotide guide sequence that is complementary to the target site. When introduced into a cell, this sgRNA directs the Cas9 nuclease to the target DNA, where it induces a DSB [6]. The cell's own repair mechanisms then mediate the final editing outcome.

Table: Key Molecular Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

| Component | Type | Function in Genome Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Protein | The effector enzyme that creates a double-strand break in the target DNA [5] [2]. |

| sgRNA (single-guide RNA) | RNA | A chimeric RNA molecule that combines the functions of crRNA and tracrRNA to guide Cas9 to a specific genomic location [1] [5]. |

| PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif) | Short DNA sequence | A short, specific sequence (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) adjacent to the target site that is essential for Cas9 recognition and binding [5] [2]. |

{c1::The Genome Editor's Toolkit: Mechanisms of DNA Repair} The cellular repair of Cas9-induced DSBs is the cornerstone of genome editing, primarily occurring via two pathways [5]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is an error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. When targeted to a gene's coding sequence, these indels can disrupt the reading frame, leading to a functional gene knockout [2]. This is highly applicable for disrupting dominant negative alleles in reproductive disorders.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This pathway uses a homologous DNA template to repair the break accurately. By co-delivering a donor DNA template with the desired sequence alongside CRISPR-Cas9, researchers can achieve precise gene correction or insertion, which is the ultimate goal for correcting most genetic mutations in the germline [5] [2].

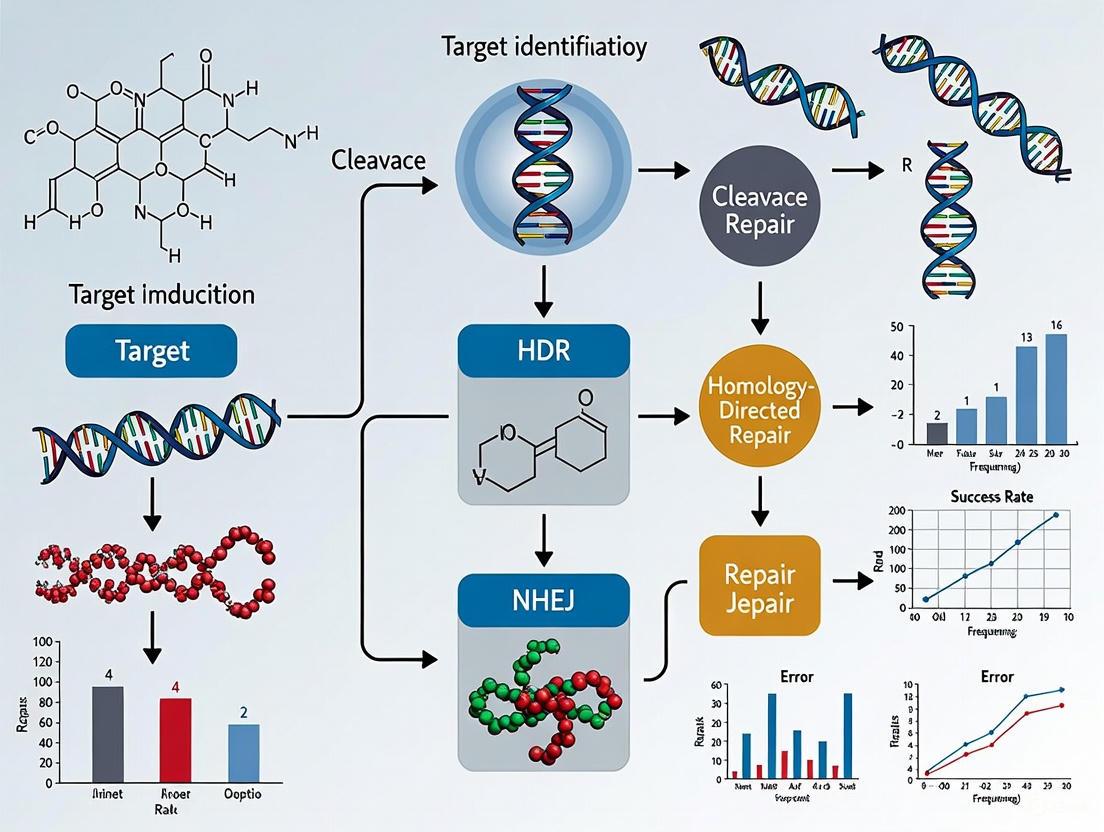

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Outcomes via DNA Repair Pathways. DSBs are repaired by the error-prone NHEJ pathway, leading to knockouts, or the precise HDR pathway using a donor template.

{c1::Advanced CRISPR-Cas Systems for Precision Surgery} The foundational CRISPR-Cas9 system has been extensively engineered to enhance its precision and expand its capabilities, moving beyond simple DSBs.

Table: Evolution of CRISPR-Based Genome Editing Tools

| Technology | Key Features | Application in Reproductive Genetics |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 [7] | Engineered Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, Cas9-HF1) with reduced off-target effects. | Increases safety profile for therapeutic editing of embryos and germ cells. |

| Base Editing [5] | Fuses a catalytically impaired Cas9 (nCas9) to a deaminase enzyme. Converts a single DNA base (C->T, A->G) without creating a DSB. | Corrects point mutations responsible for many genetic disorders (e.g., sickle cell disease) with minimal genotoxicity [8]. |

| Prime Editing [5] | Uses an nCas9 fused to a reverse transcriptase and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). Can perform all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, plus small insertions and deletions, without a DSB or donor template. | Offers unprecedented versatility for correcting a wide array of pathogenic mutations with high precision. |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) [5] | A single RNA-guided nuclease that creates staggered DNA ends. Does not require tracrRNA. Recognizes a T-rich PAM (TTTV). | Provides an alternative PAM recognition, expanding the range of targetable genomic sites for multiplexed editing. |

{c1::Experimental Protocol: A Template for Gene Editing in Reproductive Biology} The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for achieving CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knockout in a model system, adaptable for research on reproductive cells or early embryos. It is based on established plant transformation and editing workflows [9] and reflects general principles applicable to preclinical research.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Editing

| Research Reagent | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein | The core nuclease enzyme that executes the DNA cut. Using purified protein as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is favored for reduced off-target effects and transient activity [10]. |

| sgRNA (synthetic) | A chemically synthesized single-guide RNA that directs Cas9 to the specific genomic target. Using two sgRNAs can increase knockout efficiency [9]. |

| Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) | A peptide sequence fused to Cas9 that ensures its import into the cell nucleus. Recent advances with hairpin internal NLS (hiNLS) enhance editing efficiency in primary human cells [10]. |

| Delivery Vector | A plasmid or viral vector (e.g., lentivirus, AAV) engineered to express Cas9 and sgRNA(s) in target cells. For transgene-free editing, RNP delivery is preferred [9]. |

| Selection Antibiotic | An antibiotic (e.g., Kanamycin) used in culture media to select for cells that have successfully incorporated the editing machinery [9]. |

Title: CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery for Gene Knockout

Goal: To achieve a loss-of-function mutation in a target gene via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) following transfection with a pre-assembled Cas9-sgRNA RNP complex.

Materials & Reagents:

- Purified Cas9 protein with NLS (e.g., S. pyogenes Cas9)

- Chemically synthesized sgRNA(s) targeting the gene of interest

- Delivery method: Electroporation reagents for primary cells or lipid nanoparticles (LNPs)

- Cell culture media and reagents for the target cell type (e.g., primary lymphocytes, stem cells)

- Lysis buffer and PCR reagents for genotyping

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design and Validation:

- Design one or two sgRNAs targeting early exons of the target gene, preferably close to the start codon [9].

- Use computational tools (e.g., CRISPRscan) to predict on-target efficiency and minimize potential off-target sites.

- Synthesize and resuspend sgRNAs in nuclease-free buffer.

RNP Complex Assembly:

- Combine purified Cas9 protein and sgRNA at a predetermined molar ratio (e.g., 1:2) in a suitable buffer.

- Incubate the mixture at 25-37°C for 10-20 minutes to allow RNP complex formation.

Cell Transfection:

- For electroporation: Harvest and wash the target cells. Resuspend cells in an electroporation buffer, mix with the pre-assembled RNP complex, and electroporate using an optimized electrical program [10].

- For lipid-based delivery: Complex the RNP with commercial lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) according to the manufacturer's instructions and add to cells.

Culture and Expansion:

- After transfection, transfer cells to fresh pre-warmed culture medium.

- Allow cells to recover and proliferate for several days to enable repair and manifestation of edits.

Genotyping and Analysis:

- Harvest a portion of the cells 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Extract genomic DNA and perform PCR amplification of the targeted genomic region.

- Analyze the PCR products using Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) to detect the spectrum of indel mutations and calculate editing efficiency.

Figure 2: CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Knockout Workflow. Key steps from complex assembly to analysis.

{c1::Applications in Correcting Reproductive Genetic Abnormalities} CRISPR-Cas9 technology is being actively explored to correct inherited genetic mutations at various stages, from germline cells to somatic cells in adults. Its application in reproductive biology focuses on preventing the transmission of genetic diseases [3] [4].

- Germline and Embryo Editing: This approach involves correcting disease-causing mutations in sperm, eggs, or early-stage embryos. The edits would be heritable, potentially eradicating the familial disease lineage. While ethically complex and heavily regulated, this represents a definitive path for preventing monogenic disorders like cystic fibrosis, Huntington's disease, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy [4] [6].

- Therapeutic Somatic Cell Editing: Clinical success in somatic cells paves the way for related reproductive applications. The landmark approval of Casgevy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia demonstrates that CRISPR can be used to edit hematopoietic stem cells ex vivo to produce therapeutic effects [8]. This proof-of-concept supports the feasibility of developing similar ex vivo editing protocols for germline or precursor cells.

{c1::Challenges and Future Directions} Despite its promise, the translation of CRISPR-Cas9 into clinical therapies for reproductive genetic abnormalities faces several hurdles that are the focus of intense research [1] [5] [8]:

- Off-Target Effects: The potential for Cas9 to cleave at unintended, partially complementary genomic sites remains a primary safety concern. Mitigation strategies include using high-fidelity Cas9 variants, optimized sgRNA design, and RNP delivery for transient activity [10] [2].

- Efficiency and Delivery: Achieving high HDR efficiency for precise correction, especially in hard-to-transfect cells like oocytes or zygotes, is challenging. Improving delivery methods, such as the use of novel LNPs and engineered viruses, is critical.

- Ethical and Regulatory Landscapes: The application of CRISPR in human germline editing raises profound ethical questions and is subject to strict legal restrictions in many countries [6]. Ongoing international dialogue is essential to establish clear guidelines for responsible research and potential clinical use.

{c1::Conclusion} The journey of CRISPR-Cas9 from a bacterial immune mechanism to a powerful tool for precision genome surgery represents a paradigm shift in biomedical science. Its core mechanism—programmable DNA recognition and cleavage—has been refined and expanded into a versatile toolkit capable of generating knockouts and, with base and prime editors, performing precise nucleotide surgery. As research in reproductive biology leverages these tools, coupled with robust protocols and a deepening understanding of the associated challenges, the potential to correct devastating genetic abnormalities at their source moves closer to reality, heralding a new era in genetic medicine.

The application of gene editing for correcting reproductive genetic abnormalities represents a frontier in reproductive medicine. While the CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering, its reliance on double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) introduces significant limitations for clinical applications, particularly in precious and sensitive systems like human embryos. DSBs can lead to unintended outcomes such as indels (insertions/deletions), large deletions, and chromosomal rearrangements, raising safety concerns for therapeutic use [11] [12]. The emergence of more precise editing technologies—prime editing, base editing, and epigenetic modulation—offers promising alternatives that minimize these risks by editing DNA without creating DSBs.

These second-generation editing platforms significantly expand the scope of what is possible in correcting disease-causing mutations. Base editors enable efficient single nucleotide changes, prime editors function as "search-and-replace" tools for precise small edits, and epigenetic modulators allow for reversible changes in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself [11] [13] [12]. For researchers focused on reproductive genetic abnormalities, these tools provide unprecedented opportunities to study and potentially correct mutations responsible for monogenic diseases such as sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, and Tay-Sachs disease at the earliest stages of development. This article provides application notes and detailed protocols for implementing these advanced technologies in embryo research, framed within the context of correcting pathogenic alleles while maintaining the highest standards of precision and safety.

Technical Comparative Analysis of Editing Platforms

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three primary precision editing platforms relevant to embryo research:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Precision Genome Editing Platforms

| Editing Platform | Molecular Mechanism | Editing Window/Precision | Primary Applications in Embryo Research | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Editing | Cas9 nickase or dCas9 fused to deaminase enzymes converts C•G to T•A (CBE) or A•T to G•C (ABE) without DSBs [14] [12]. | ~5 nucleotide window near PAM site; high efficiency but limited positioning [15]. | Correcting point mutations causing monogenic diseases (e.g., β-thalassemia, sickle cell) [16]. | Cannot generate all possible base substitutions; requires specific positioning relative to PAM sequence [11]. |

| Prime Editing | Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion uses pegRNA to directly write new genetic information into DNA [11] [17]. | Highly precise; can install all 12 possible base substitutions, small insertions (up to 44bp), and deletions (up to 80bp) [11]. | Correcting pathogenic alleles not addressable by base editors, including transversions and small indels. | Efficiency can be variable and lower than base editors; requires optimization of pegRNA and possible MMR inhibition [11] [17]. |

| Epigenetic Modulation | dCas9 fused to epigenetic effector domains (e.g., DNMT3A for methylation, TET1 for demethylation) modifies chromatin marks without changing DNA sequence [13] [18]. | Targets specific loci to alter DNA methylation or histone modifications; effects can be tunable and potentially reversible [13]. | Studying genomic imprinting, activating silenced alleles, and potentially modulating disease risk without permanent DNA alteration. | Effects may be transient; efficiency and specificity of sustained modulation require careful validation [13]. |

Prime Editing: A Versatile "Search-and-Replace" Tool

Mechanism and Workflow

Prime editing represents a significant leap in precision editing technology. The system employs a fusion protein consisting of a Cas9 nickase (H840A) connected to an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) from the Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV), along with a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) [11] [17]. The pegRNA not only specifies the target site but also contains a primer binding site (PBS) and an RT template encoding the desired edit. The mechanism involves: (1) binding of the prime editor complex to the target DNA, (2) nicking of the non-target DNA strand by the Cas9 nickase, (3) hybridization of the 3' end of the nicked DNA to the PBS on the pegRNA, (4) reverse transcription of the edited sequence from the RT template, and (5) resolution and repair of the DNA heteroduplex to permanently incorporate the edit [11]. The development of advanced prime editors (PE2-PE7) with improved RT efficiency and pegRNA stability (epegRNAs) has substantially increased editing efficiencies [17].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of prime editing:

Application Notes for Embryo Research

Prime editing is particularly suited for correcting mutations in embryos where precision is paramount. Its ability to install all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, means it can theoretically correct up to 89% of known pathogenic human genetic variants [11]. For reproductive genetics, this includes mutations in genes like HEXA (Tay-Sachs disease), CFTR (cystic fibrosis), and F8 (hemophilia A), where different families may carry distinct mutations that can all be addressed with a single, versatile platform.

Key optimization strategies for embryo editing include:

- pegRNA Design: The PBS should be 10-15 nucleotides long, and the RT template should extend 8-10 nucleotides beyond the edit. The use of engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) with structured RNA motifs at the 3' end protects against exonuclease degradation and improves efficiency [11] [17].

- MMR Inhibition: Co-expression of dominant-negative mutants of the MLH1 protein (as in PE4 and PE5 systems) can transiently inhibit the mismatch repair pathway, which often favors the non-edited strand and reduces editing efficiency. This can increase prime editing efficiency by several-fold [11].

- Delivery Considerations: For embryo work, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery of the prime editor protein complexed with in vitro-transcribed pegRNA may minimize off-target effects and reduce exposure time, potentially improving embryo viability [19].

Base Editing: Efficient Single Nucleotide Correction

Mechanism and Workflow

Base editors provide a highly efficient method for converting one DNA base pair to another without requiring DSBs. Two main classes have been developed: Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) convert C•G to T•A, and Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) convert A•T to G•C [14] [12]. CBEs are typically fusions of a Cas9 nickase (or dCas9) to a cytidine deaminase enzyme (like APOBEC1) and a uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) that prevents unwanted repair of the edited base. ABEs use an evolved tRNA adenosine deaminase (TadA) to perform the A-to-I conversion, which the cell then treats as G [14] [15] [12]. The editing occurs within a defined "editing window" of approximately 5 nucleotides near the PAM site, making target site positioning crucial.

The workflow for base editing involves:

- Target Site Selection: Identifying a target site where the pathogenic base falls within the editing window of a suitable PAM sequence.

- Editor Delivery: Introducing the base editor and sgRNA into the cells, typically as plasmids, mRNA, or RNP complexes.

- Editing Validation: Using mismatch cleavage assays, Sanger sequencing, or next-generation sequencing to quantify editing efficiency and byproducts [15] [19].

Application Notes for Embryo Research

Base editors are particularly valuable for correcting specific point mutations known to cause severe genetic disorders. For instance, the mutation responsible for Progeria (LMNA c.1824C>T) or the sickle cell disease mutation (HBB c.20A>T) are theoretically correctable with base editing technology [12]. The high efficiency and reduced indel formation compared to CRISPR-Cas9 make base editors attractive for embryo editing where maximizing correct editing while minimizing collateral damage is critical.

Key considerations for embryo base editing include:

- Editing Window: The protospacer must be positioned so that the target base falls within the ~5-nucleotide activity window of the base editor, typically at positions 4-8 within the protospacer, counting the PAM as positions 21-23 [15].

- Byproduct Management: While base editors produce fewer indels than Cas9 nuclease, they can cause unwanted, low-frequency "bystander" edits when multiple editable bases are present in the activity window. Careful design and analysis are required to select targets that minimize this risk [15] [12].

- Variant Selection: Newer base editor variants with narrowed or shifted editing windows (e.g., BE4, Target-AID) can improve product purity when multiple cytosines or adenines are present in the original window [12].

Epigenetic Modulation: Regulating Gene Expression Without Changing DNA Sequence

Mechanism and Experimental Setup

Epigenetic modulation using CRISPR/dCas9 systems allows for precise alteration of gene expression patterns without modifying the underlying DNA sequence—an approach particularly relevant for studying imprinted genes and regulatory elements during embryonic development. This technology fuses a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) to epigenetic effector domains, such as DNMT3A for adding DNA methylation marks or TET1 for removing them [13] [18]. When guided to specific genomic loci by sgRNAs, these fusion proteins can induce targeted epigenetic remodeling, leading to stable changes in gene transcription that can persist through multiple cell divisions [13].

Advanced systems enable orthogonal epigenetic editing, where different dCas9 orthologs (e.g., dSpCas9 and dSaCas9) fused to opposing epigenetic modifiers (e.g., DNMT3A and TET1) can be used simultaneously within the same cell to study antagonistic epigenetic regulation [13]. Furthermore, synergistic effects have been demonstrated by combining epigenetic activators like VPR-dSpCas9 with TET1-dSaCas9, resulting in strong and persistent gene activation lasting up to 30 days post-transfection [13].

Application Notes for Embryo Research

In the context of embryo research and correcting genetic abnormalities, epigenetic modulation offers a potentially safer alternative for conditions where altering gene expression, rather than the genetic code itself, may provide therapeutic benefit. This includes potentially reactivating silenced healthy alleles of imprinted genes or modulating the expression of genes involved in metabolic storage diseases.

Key implementation strategies include:

- Modular Toolboxes: Utilizing modular cloning systems (e.g., Golden Gate assembly) allows for flexible testing of different effector domain combinations and sgRNA configurations to optimize editing outcomes [13].

- Multi-guide Systems: Employing systems capable of expressing up to six different sgRNAs simultaneously enables effective targeting of larger regulatory regions, such as promoters and enhancers, which often require multiplexed guidance for effective modulation [13].

- Stability Optimization: The persistence of epigenetic changes can be enhanced by using stronger chromatin-opening effectors like VPR and combining them with demethylating enzymes like TET1, as demonstrated in sustained activation of the HNF1A gene [13].

Essential Reagents and Validation Methods

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these advanced editing technologies requires careful selection of molecular tools and reagents. The following table catalogs essential reagents for precision genome editing in embryonic systems:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Precision Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Editors | PE2, PEmax, PE4, PE5, PE6, PE7 | Engineered fusion proteins with improved efficiency and specificity; PE4/PE5 include MMR inhibition. | [11] [17] |

| Base Editors | BE3, BE4, Target-AID, ABE7.10 | CBEs and ABEs with varying editing windows, efficiencies, and fidelity characteristics. | [14] [15] [12] |

| Epigenetic Effectors | dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-TET1, dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-VPR | Fusion proteins for targeted DNA methylation, demethylation, repression, and activation. | [13] [18] |

| Specialized Guide RNAs | pegRNA, epegRNA, nicking sgRNA (for PE3/5) | pegRNAs encode the edit; epegRNAs have enhanced stability; nicking sgRNAs enhance PE efficiency. | [11] [17] |

| Delivery Tools | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation, AAV vectors | Methods for introducing editing components into embryos and cells; LNPs allow potential re-dosing. | [16] |

| Validation Enzymes | T7 Endonuclease I, ArciTect T7 Endonuclease I | Detects indels and editing efficiency via mismatch cleavage assays in heterogeneous cell populations. | [19] |

| AV023 | Ankrd22-IN-1 | ANKRD22 Inhibitor for Research Use | Bench Chemicals | |

| 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde-d5 | 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde-d5, MF:C7H5NO3, MW:156.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Prime Editing in Embryos

The following protocol outlines key steps for implementing a prime editing experiment in a research setting, incorporating validation steps critical for assessing success.

Table 3: Protocol for Prime Editing Experiment Implementation and Validation

| Step | Procedure | Purpose & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Target Selection & pegRNA Design | Identify target sequence and design pegRNA with 10-15 nt PBS and RT template encoding the desired edit. Use computational tools (e.g., DeepPrime). | Ensures the edit is positioned correctly. For difficult targets, design multiple pegRNAs to test. |

| 2. Component Delivery | Deliver prime editor (as mRNA or protein) and pegRNA (as in vitro transcript) into zygotes via microinjection or electroporation. | RNP delivery may reduce off-target effects. Optimize concentrations to balance efficiency and viability. |

| 3. Initial Screening (48-72 hrs) | Extract genomic DNA from a subset of embryos. Amplify target region with offset primers. Perform T7 Endonuclease I assay [19]. | Rapid assessment of editing activity. The assay cleaves heteroduplex DNA, giving an estimate of editing frequency. |

| 4. Deep Sequencing Validation | Amplify target region from pooled embryos or individual clones. Submit for next-generation sequencing (NGS). Analyze with CRISPResso2 [19]. | Provides quantitative data on editing efficiency, precision, and byproducts (indels, bystander edits). |

| 5. Off-Target Assessment | Amplify potential off-target sites (predicted by in silico tools) and sequence. Alternatively, perform whole-genome sequencing for comprehensive analysis. | Critical for safety assessment. NGS provides the most thorough evaluation of off-target effects. |

| 6. Functional Validation | For established embryo models, assess phenotypic correction, protein expression restoration, and developmental progression. | Confirms that the genetic correction translates to functional and developmental improvement. |

The rapid evolution of precision genome editing tools has dramatically expanded our capabilities for researching and potentially correcting reproductive genetic abnormalities. Prime editing, base editing, and epigenetic modulation each offer distinct advantages and applications, together creating a comprehensive toolkit for addressing a wide spectrum of genetic diseases at the embryonic stage. As these technologies continue to advance—with improvements in editing efficiency, specificity, and delivery—their potential for clinical translation in reproductive medicine will grow accordingly.

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing the efficiency and specificity of these editors, optimizing delivery methods such as lipid nanoparticles that allow for re-dosing [16], and establishing robust safety profiles through comprehensive off-target characterization. Furthermore, the combination of these approaches—such as using epigenetic modulation to prime a locus for more efficient editing—may open new therapeutic avenues. For researchers in reproductive genetics, these technologies provide not only powerful tools for fundamental research into human development and disease but also hope for future interventions that could prevent the transmission of devastating genetic disorders.

The application of gene-editing technologies to correct reproductive genetic abnormalities represents a frontier in biomedical science with profound implications. This field, known as heritable human genome editing (HHGE), aims to prevent the transmission of serious genetic diseases by introducing precise modifications into the DNA of sperm, eggs, or embryos. The journey from the first controversial birth of gene-edited children to the current rise of commercial ventures illustrates a critical pivot point in reproductive medicine. This article details the key studies and emerging protocols shaping this field, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in this rapidly evolving discipline. The content is framed within the broader thesis that HHGE, while not yet safe or refined enough for clinical application, holds significant potential for preventing monogenic diseases, necessitating rigorous, transparent, and collaborative research to establish safety and efficacy protocols.

Landmark Historical Case: The He Jiankui Affair

In 2018, Chinese biophysicist He Jiankui announced the birth of the world's first genetically edited babies, twin girls known pseudonymously as Lulu and Nana [20]. His objective was to confer genetic resistance to HIV by mimicking a naturally occurring mutation in the CCR5 gene, which codes for a protein HIV uses to enter cells [20]. The target population was children of HIV-positive fathers and HIV-negative mothers, who faced social and regulatory barriers to assisted reproduction in China [20].

Detailed Methodology and Protocol

The following protocol reconstructs the methodology employed based on available public reports and summaries [20].

Protocol 1: Embryonic CCR5 Gene Editing for HIV Resistance

- 1. Patient Recruitment & Informed Consent: Recruit couples through AIDS advocacy groups, offering standard in vitro fertilisation (IVF) services with an experimental gene-editing component. The informed consent process was later widely criticized as being incomplete and inadequate [20].

- 2. In Vitro Fertilisation: Perform standard IVF procedures using sperm from the HIV-positive father and eggs from the HIV-negative mother to create zygotes.

- 3. Microinjection of CRISPR-Cas9 Components: Shortly after fertilisation, microinject the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery into the embryos. The editing complex was designed to introduce a frameshift mutation intended to disable the CCR5 gene, rather than recreate the natural CCR5-Δ32 variant [20].

- 4. Embryo Culture & Quality Control: Culture the edited embryos. Employ a preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) process, removing 3-5 cells from each embryo for comprehensive genetic sequencing to identify potential mosaicism (where some cells are edited and others are not) and off-target editing events [20].

- 5. Embryo Transfer: Select embryos based on PGD results for transfer into the mother's uterus to establish a pregnancy.

- 6. Prenatal Monitoring: During pregnancy, sequence cell-free fetal DNA from the mother's blood to monitor for off-target effects. Offer amniocentesis for further genetic analysis, though this was declined by the parents in the reported case [20].

Key Outcomes and Data

The experiment resulted in the birth of twin girls in October 2018 [20]. He Jiankui reported that the babies were born healthy and that genetic sequencing indicated the intended edits were present, albeit with some mosaicism [20]. A third gene-edited child was born in 2019 [20]. The data was never peer-reviewed or published in a scientific journal, and the claims lack independent verification [20].

Table 1: Quantitative Data Summary of the He Jiankui Experiment

| Parameter | Reported Outcome | Limitations & Criticisms |

|---|---|---|

| Target Gene | CCR5 | The edit did not replicate the natural CCR5-Δ32 mutation; some HIV strains use other receptors (e.g., CXCR4), so protection is not guaranteed [20]. |

| Number of Embryos/Babies | 3 babies born (Twins Lulu & Nana, plus a third child, Amy) | The existence of a third child was not initially disclosed [20]. |

| Editing Efficiency | Reported edits present, but with mosaicism | Mosaicism means the edit is not present in all cells, potentially undermining the therapeutic goal and complicating risk assessment [20]. |

| Off-Target Analysis | Performed via PGD and cell-free fetal DNA sequencing | The adequacy and sensitivity of these methods for a comprehensive off-target profile are debated. No independent data verification exists [20]. |

| Clinical Outcome | Babies reported healthy at birth | The long-term health consequences, including cancer risk from potential off-target edits, are entirely unknown [20]. |

Aftermath and Global Response

The experiment was met with immediate and widespread international condemnation from scientists, bioethicists, and governments [20]. Criticisms centered on the profound ethical breaches, including the secretive nature of the work, the inadequate informed consent process, the unknown long-term risks to the children, and the use of an unproven and unnecessary procedure on otherwise healthy embryos [20]. In December 2019, a Chinese court found He Jiankui and two collaborators guilty of illegal medical practice, sentencing him to three years in prison [20]. The affair prompted global calls for a moratorium on HHGE and spurred the World Health Organization and numerous national governments to develop stricter guidelines for human genome editing [20].

Current Commercial Ventures in Embryonic Gene Editing

The controversial legacy of He Jiankui has not deterred a new wave of commercial ventures, primarily backed by Silicon Valley investors, who are pushing to advance HHGE with a stated focus on disease prevention.

Table 2: Overview of Current Commercial Ventures in HHGE

| Venture Name | Key Leadership/Backing | Stated Mission & Focus | Reported Funding & Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preventive [21] [22] [23] | Lucas Harrington (co-founder); Backed by OpenAI's Sam Altman and Coinbase's Brian Armstrong. | To research and rigorously test the safety of heritable genome editing for preventing serious genetic diseases [21]. | Approximately $30 million from private funders [21] [23]. Incorporated as a public-benefit corporation. Research is planned outside the US due to regulatory barriers [22] [23]. |

| Manhattan Genomics [24] | Cathy Tie (CEO), Eriona Hysolli (co-founder). | To prevent serious genetic diseases like cystic fibrosis and beta thalassemia through embryonic gene editing, with a focus on transparency and regulatory approval [24]. | Funding amount not publicly disclosed. Company is in the formation stage [24]. |

| Bootstrap Bio [24] | Chase Denecke (CEO). | Initially focused on disease prevention but has expressed interest in enhancing traits to "make peoples' lives actually better" [24]. | Reportedly seeking seed funding [21]. |

Proposed Research and Development Workflow

These companies emphasize a more measured, scientifically rigorous approach compared to the He Jiankui case. Their proposed R&D pipeline can be visualized as a multi-stage, iterative process.

Diagram 1: Proposed R&D Pipeline for HHGE

Stated Experimental Protocols for Safety Assessment

Ventures like Preventive and Manhattan Genomics have stated their commitment to extensive safety testing before any clinical application. The following protocol outlines the key methodologies they propose to employ.

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Safety and Efficacy Assessment for HHGE

1. In Vitro and In Silico Modeling:

- Objective: To perform initial gRNA design and off-target prediction.

- Method: Utilize human cell lines and advanced computational tools to design and screen guide RNAs (gRNAs) for high on-target efficiency and minimal predicted off-target activity. This includes using tools like CIRCLE-seq for in vitro off-target profiling.

2. Animal Model Studies:

- Objective: To assess the feasibility, specificity, and developmental impact of editing in a whole organism.

- Method: Conduct gene-editing experiments in mouse and non-human primate embryos. This involves:

- Microinjection of CRISPR machinery into zygotes.

- Transfer of viable embryos to surrogate females.

- Comprehensive genomic analysis of resulting offspring via whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to confirm on-target editing and detect off-target effects and mosaicism.

- Long-term phenotyping to monitor health, development, and reproductive fitness across generations.

3. Research on Non-Implantable Human Embryos:

- Objective: To validate editing efficiency and safety in the human context.

- Method: Use donated human embryos created via IVF that are not destined for implantation. Perform gene editing and culture them for up to 14 days (in accordance with international guidelines). Analyze embryos at various developmental stages using:

- Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS): To comprehensively map on-target and off-target edits.

- Transcriptomics and Epigenomics: To assess any unintended disruptions to gene expression and cellular function.

- Single-Cell Multi-omics: To understand cell lineage and mosaicism at high resolution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The advancement of HHGE research relies on a suite of sophisticated tools and reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HHGE

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Application in HHGE |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems (Cas9, Cas12a) | The core gene-editing enzymes that create double-strand breaks in DNA at programmed locations. Different systems (e.g., Cas9 vs. Cas12a) offer variations in specificity and the type of DNA cut made [8]. |

| Base Editors & Prime Editors | Advanced "CRISPR 2.0" systems that allow for precise chemical conversion of a single DNA base (e.g., C to T) or the insertion of small sequences without creating double-strand breaks, potentially reducing off-target effects and increasing safety [16] [24]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery vehicle for in vivo gene editing. While currently used primarily in somatic therapies, LNPs are a subject of intense research for their potential to deliver editing components to gametes or embryos more safely and efficiently than current methods [16]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | A short RNA sequence that programs the Cas enzyme to bind to a specific target site in the genome. Its design is critical for minimizing off-target effects [20]. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) Kits | Essential reagents for the comprehensive analysis of edited cells or embryos. Used to confirm on-target edits and, crucially, to detect any off-target mutations across the entire genome, a core component of safety assessment [20]. |

| Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT) Reagents | Used to genetically screen embryos prior to transfer. In the context of HHGE research, these reagents are critical for analyzing edit status (e.g., mosaicism) in blastocyst-stage embryos in a non-destructive manner [20]. |

| Antileishmanial agent-4 | Antileishmanial agent-4|Leishmania Research|RUO |

| AHR antagonist 4 | AHR antagonist 4, MF:C20H14F6N4O4, MW:488.3 g/mol |

The path from He Jiankui's ethically and scientifically flawed experiment to the current, more transparent commercial ventures marks a significant evolution in the field of heritable human genome editing. While the ultimate goal of preventing devastating genetic diseases remains a powerful motivator, the scientific community maintains that the technology is not yet ready for clinical application. The key challenges of off-target editing, mosaicism, and long-term health effects persist. The success of these new ventures, and the field at large, will depend on an unwavering commitment to rigorous, open, and collaborative science, robust regulatory oversight, and inclusive public dialogue. The protocols and tools outlined herein provide a framework for the meticulous research required to determine whether HHGE can ever be performed safely and responsibly, turning a controversial concept into a viable therapeutic pathway for preventing reproductive genetic abnormalities.

The global regulatory landscape for human genome editing is dynamic and multifaceted, characterized by rapid scientific progress alongside complex ethical and policy challenges. Recent advances, particularly in personalized gene-editing therapies, have prompted significant regulatory innovations, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) new pathway for accelerated approval of customized treatments [25]. Simultaneously, the international community continues to grapple with the profound implications of germline editing, evidenced by ongoing calls for moratoria and major international summits focused on establishing ethical boundaries [26] [27].

This application note provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of the current regulatory frameworks, emphasizing practical experimental protocols and resources for navigating this evolving landscape. The information is particularly framed within the context of correcting reproductive genetic abnormalities, a field that demands careful consideration of both technical feasibility and ethical permissibility.

Global Regulatory Frameworks and Quantitative Analysis

Regulatory approaches to human genome editing vary significantly across international jurisdictions, particularly regarding heritable modifications versus somatic cell therapies. The following table summarizes the key regulatory positions and restrictions of major international bodies and countries.

Table 1: Global Regulatory Positions on Human Genome Editing

| Country/Region | Somatic Cell Editing | Germline Editing (Reproductive Use) | Key Regulations/Guidelines | Penalties for Violations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Permitted with FDA oversight [28] [29] | Moratorium on clinical trials; FDA prohibited from reviewing applications [27] [29] | FDA & NIH Guidelines [29] | N/A (Regulatory block) |

| China | Permitted with oversight | Banned (Based on guidelines) [29] | Chinese Guideline on Human Assisted Reproductive Technologies [29] | Criminal sentence (e.g., 3 years imprisonment in He Jiankui case) [29] |

| United Kingdom | Permitted with oversight | Restricted; legal permission possible for specific medical uses [29] | Legislation on mitochondrial replacement [29] | Up to 10 years imprisonment [29] |

| France | Permitted with oversight | Banned (Based on legislation) [29] | Specific laws against germline editing [29] | Up to 20 years imprisonment [29] |

| International Bodies | N/A | Call for moratorium by leading scientific societies [27] [30] | Declaration of Helsinki [29] | No legal force, but provides global guidance |

A critical development in the U.S. is the FDA's proposal of a "plausible mechanism" pathway. This innovative regulatory approach allows for the approval of bespoke gene-editing medicines for patients with the same clinical syndrome, irrespective of the specific underlying mutation, based on a scientifically sound mechanism and consistent, robust patient-to-patient efficacy [28]. This is particularly significant for rare disease treatment, where commercial development is often not feasible.

Table 2: FDA's Proposed "Plausible Mechanism" Pathway for On-Demand Gene Editing

| Pathway Element | Description | Implication for Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Target Population | Patients with the same clinical syndrome (e.g., specific metabolic disorder, immune deficiency) [28] | Enables "umbrella trials" that pool patients with different mutations in the same gene or pathway. |

| Evidence Standard | Consistent, robust efficacy across a small number of patients that cannot be expected with standard care [28] | Reduces the clinical evidence burden compared to traditional drug approval pathways. |

| Manufacturing | "Platformization" of CRISPR; streamlined development for subsequent similar therapies [28] | Allows academic centers and industry to amortize development costs across multiple patient-specific therapies. |

| Current Limitations | Primarily applicable to diseases affecting tissues amenable to non-viral delivery (e.g., liver, blood stem cells) [28] | Therapies for neurological diseases await improved delivery technologies (e.g., safer AAV vectors). |

Experimental Protocols for Preclinical Development

Navigating the path to clinical trials, especially under new regulatory frameworks, requires robust and standardized preclinical protocols. The following section details a core methodology based on the pioneering case of KJ Muldoon, the first infant treated with a bespoke base-editing therapy for CPS1 deficiency [31].

Protocol: Development of a Bespoke Gene Editor for a Monogenic Disorder

This protocol outlines the key steps for designing, validating, and preparing an investigational gene-editing therapy for a single patient with a rare, life-threatening genetic condition, based on the methodologies successfully employed by the CHOP/Penn team [31].

1. Patient Identification & Genetic Diagnosis

- Objective: Confirm a definitive genetic diagnosis of a severe monogenic disease where conventional treatments are inadequate or high-risk.

- Methods:

- Perform whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing on the patient to identify the causative mutation(s).

- For recessive disorders, confirm bi-allelic presence of the pathogenic variant.

- For disorders like urea cycle defects (e.g., CPS1), monitor blood ammonia levels and other relevant biomarkers to establish disease severity and urgency [31].

2. Guide RNA (gRNA) and Editor Design

- Objective: Design a highly specific gene-editing system targeting the patient's unique mutation.

- Methods:

- Sequence Analysis: Align the wild-type and mutant gene sequences to identify the precise nucleotide change and its genomic context.

- gRNA Selection: Design a gRNA that directs the editor (e.g., a base editor) to the immediate vicinity of the target mutation with high predicted on-target efficiency and minimal off-target risk using tools like CRISPRscan.

- Editor Selection: For point mutations, select an appropriate adenine or cytosine base editor to achieve the desired nucleotide conversion without causing a double-strand break [31].

3. In Vitro Potency and Specificity Validation

- Objective: Demonstrate that the designed editor corrects the mutation efficiently and accurately in a relevant cellular model.

- Methods:

- Cell Transfection: Deliver the editor mRNA and synthetic gRNA into patient-derived fibroblasts or iPSCs (if available and time permits), or a relevant human cell line engineered to carry the patient's mutation.

- Efficiency Analysis: After 48-72 hours, extract genomic DNA and use next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantify the percentage of alleles corrected at the target site.

- Specificity Analysis: Perform computational prediction of off-target sites based on the gRNA sequence. Use methods like GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq on edited cells to empirically identify and quantify off-target editing events. NGS of these top predicted sites should be conducted to confirm specificity [28].

4. In Vivo Efficacy and Safety Studies (Animal Model)

- Objective: Provide proof-of-concept for functional correction and preliminary safety data in a live organism.

- Methods:

- Animal Model: Utilize a mouse model with the analogous disease-causing mutation. If unavailable, use a wild-type mouse for initial biodistribution and toxicity studies.

- Dose-Finding: Administer the therapy (e.g., LNP-packaged editor mRNA and gRNA) via the intended clinical route (e.g., intravenous infusion) at escalating doses.

- Efficacy Assessment: Measure the restoration of normal metabolic or physiological function (e.g., reduction in ammonia for urea cycle disorders) and detect the presence of the corrected gene sequence in the target tissue (e.g., liver) via NGS.

- Safety Assessment: Monitor animals for acute toxicity, weight loss, and signs of organ distress. Conduct histopathological analysis of major organs post-treatment [28] [31].

5. Formulation and GMP-compliant Manufacturing

- Objective: Produce a clinical-grade therapeutic for human administration.

- Methods:

- Formulation: For liver-targeted delivery, formulate the editor mRNA and gRNA in a lipid nanoparticle (LNP) system optimized for hepatocyte uptake.

- Manufacturing: Under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) conditions, produce a sufficient quantity of the drug product for the clinical dose regimen.

- Quality Control: Perform rigorous testing for potency, purity, sterility, and endotoxin levels. Given the single-patient nature, the FDA may permit "benefit-risk commensurate" accelerated small-scale manufacture with reduced testing compared to large-scale commercial production [28].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows in Gene Editing Regulation

The regulatory decision-making process for approving a novel gene-editing therapy, particularly under the new "plausible mechanism" pathway, involves a logical sequence of evaluations. The diagram below maps this workflow.

The scientific and ethical rationale for a global moratorium on heritable human genome editing (HHGE) is founded on a series of interconnected concerns, which are visually summarized in the following pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The successful development of a gene-editing therapeutic relies on a core set of reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials and their functions, drawing from the technologies used in recent landmark studies [28] [31].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Developing Gene-Editing Therapies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations for Regulatory Compliance |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Nucleases(e.g., SpCas9, base editors) | Enzymes that catalyze the cutting or chemical conversion of DNA at a target site. | Select high-specificity variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9). Document source and sequence. Requires purity and identity testing for GMP. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA)(synthetic or in vitro transcribed) | A short RNA sequence that directs the nuclease to the specific genomic target. | Design with thorough off-target prediction analysis. For GMP, require high purity, sequence verification, and endotoxin testing. |

| Delivery Vector(e.g., LNP, AAV, EV) | A vehicle to protect and deliver the gene-editing machinery into target cells in the body. | LNP: Ideal for liver-directed editing [28]. AAV: Used for other tissues but has manufacturing challenges [28]. Characterize size, charge, and encapsulation efficiency. |

| Patient-Derived Cells(e.g., iPSCs, fibroblasts) | A cellular model for in vitro validation of editing efficiency and specificity. | Establish with informed consent. Maintain genomic stability and identity. Crucial for demonstrating target engagement in the relevant genetic background. |

| NGS Off-Target Assay Kits(e.g., GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq) | Tools to empirically identify and quantify unintended editing events across the genome. | Essential for preclinical safety package. Data from these assays are typically required by regulators to assess product risk. |

| Reference Standards(e.g., synthetic genes) | Controls for sequencing and analytical assays to ensure accuracy and reproducibility. | Critical for validating NGS-based potency and off-target assays. Should be traceable and well-characterized. |

| Probucol-d6 | Probucol-d6 Stable Isotope | |

| Cr(III) protoporphyrin IX | Cr(III) protoporphyrin IX, MF:C34H31CrN4O4, MW:611.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The global regulatory landscape for gene editing is at a pivotal juncture. The emergence of faster FDA pathways for personalized therapies represents a monumental shift for treating severe rare diseases, effectively creating a new category of medicine [25] [28]. However, this progress stands in stark contrast to the firm and enduring international consensus supporting a moratorium on heritable human genome editing, a position reinforced by leading scientific societies as recently as 2025 [27].

For researchers focused on correcting reproductive genetic abnormalities, this dichotomy defines the field. The immediate future lies in refining somatic cell therapies and navigating the new "platform" and "umbrella trial" regulatory models. The successful treatment of KJ Muldoon for CPS1 deficiency provides a tangible protocol for this approach [31]. Meanwhile, any research involving germline modifications must proceed with extreme caution, adhering to the strictest ethical guidelines and current legal prohibitions. The ongoing dialogue, exemplified by the 2025 Global Observatory International Summit, underscores that responsible innovation requires continuous, inclusive deliberation to ensure these powerful technologies serve humanity and uphold the integrity of human life [26] [32].

This application note provides a comparative analysis of therapeutic target identification and experimental protocols for two distinct categories of genetic disorders: monogenic diseases and complex reproductive disorders. Within the expanding field of gene editing, these categories present unique challenges and opportunities for researchers and drug development professionals. We outline specific methodological approaches, technical considerations, and research tools essential for advancing targeted therapies in both domains, with particular emphasis on CRISPR-based technologies for monogenic conditions and integrated pathway targeting for complex reproductive endocrine disorders.

The strategic approach to identifying and validating therapeutic targets varies substantially between monogenic diseases and complex reproductive disorders. Monogenic diseases, caused by mutations in a single gene, offer well-defined, causal targets for direct genetic correction [33] [34]. In contrast, complex reproductive disorders often involve polygenic inheritance, environmental influences, and dysregulation of intricate neuroendocrine signaling pathways, necessitating multi-target intervention strategies [35] [36].

The emergence of precision gene editing tools, particularly CRISPR-Cas systems and their derivatives (base editing, prime editing), has revolutionized therapeutic development for monogenic conditions [33] [37]. Meanwhile, advances in functional neuroimaging and multi-omics profiling have enhanced our understanding of the complex pathophysiology underlying reproductive disorders, revealing novel intervention points within the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis [35].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics Influencing Target Identification

| Characteristic | Monogenic Diseases | Complex Reproductive Disorders |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | Single gene mutation [38] | Polygenic + environmental factors [35] |

| Primary Target | Causal gene/variant [33] | Signaling pathways & regulatory networks [35] |

| Therapeutic Approach | Direct genetic correction [33] | Multi-target modulation [35] |

| Target Validation | Genetic linkage, functional restoration assays | Pathway analysis, neuroimaging, endocrine profiling [35] |

| Example Targets | BCL11A (hemoglobinopathies), CFTR (cystic fibrosis) [34] [39] | Kisspeptin-GPR54, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, BDNF-TrkB [35] |

Therapeutic Targeting for Monogenic Diseases

Target Identification and Validation

Monogenic disease targets are identified through genetic sequencing of affected individuals and families to establish causal relationships between gene mutations and disease phenotypes. Target validation involves demonstrating that correction of the specific genetic lesion rescues cellular and physiological function.

Key Considerations:

- Variant Pathogenicity: Establish clinical significance using databases such as ClinVar and functional studies [33].

- Therapeutic Window: Assess the editing activity window relative to the pathogenic mutation for base editing approaches [33].

- Delivery Constraints: Consider target tissue accessibility and editing tool delivery limitations [37].

Table 2: Quantitative Considerations for Monogenic Disease Target Selection

| Parameter | Optimal Characteristics | Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Frequency | High prevalence in patient populations [38] | Population genetics databases |

| Editing Window | Within 5-10 nucleotide activity window for base editors [33] | In vitro editing efficiency assays |

| Therapeutic Threshold | 10-24% of normal expression may be sufficient (e.g., CFTR) [34] | Gene expression analysis, functional assays |

| PAM Availability | NGG for SpCas9; T-rich for Cas12a; engineered variants for relaxed PAM [37] | PAM prediction algorithms, target sequence analysis |

Experimental Protocol: Base Editing for Point Mutation Correction

This protocol describes a methodology for correcting pathogenic point mutations using CRISPR-dependent base editing in patient-derived cells.

Materials:

- Patient-derived fibroblasts or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

- Appropriate base editor plasmid (ABE or CBE based on conversion required)

- sgRNA expression construct or synthetic sgRNA

- Delivery system (electroporation, lipofection, or AAV)

- Culture media and supplements

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents

- Sequencing primers

- Functional assay reagents (dependent on gene function)

Procedure:

Target Analysis and sgRNA Design

- Identify the pathogenic single-nucleotide variant (SNV) and sequence context

- Design sgRNA to position the target base within the activity window (typically positions 4-8 for ABE, 3-10 for CBE) [33]

- Verify minimal off-target potential using algorithms like CRISPRseek or Cas-OFFinder

- Check for required PAM sequence (NGG for SpCas9-based editors)

Editor Assembly and Delivery

- Clone sgRNA sequence into appropriate base editor backbone (e.g., pCMV_ABE8e for A•T to G•C conversion)

- Propagate plasmid in Endura electrocompetent E. coli with appropriate antibiotic selection

- Prepare high-purity plasmid DNA using endotoxin-free maxiprep kit

- Deliver base editor components to 70-80% confluent cells using optimized electroporation parameters (e.g., Neon Transfection System, 1400V, 20ms, 2 pulses)

Editing Efficiency Validation

- Harvest cells 72-96 hours post-editing

- Extract genomic DNA using silica membrane columns

- Amplify target region by PCR with high-fidelity polymerase

- Quantify editing efficiency using next-generation sequencing (minimum 10,000x coverage) or restriction fragment length polymorphism (if editing creates/disrupts a site)

- Calculate efficiency as percentage of edited alleles in total reads

Functional Validation

- Differentiate edited iPSCs into relevant cell type (if applicable)

- Assess protein expression by western blot or immunofluorescence

- Perform disease-specific functional assays (e.g., forskolin-induced swelling for CFTR in intestinal organoids [34])

- Evaluate cell viability and proliferation to exclude toxicity

Off-Target Assessment

- Perform whole-genome sequencing or target-specific amplification of predicted off-target sites

- Analyze chromosomal rearrangements at target locus by long-range PCR

- Assess p53 activation stress response via western blot for p21 and p53 phosphorylation

Therapeutic Targeting for Complex Reproductive Disorders

Target Identification and Validation

Complex reproductive disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, and premature ovarian insufficiency involve dysregulated signaling networks within the neuroendocrine-reproductive axis [35]. Target identification requires systems-level analysis of disrupted pathways rather than single gene defects.

Key Considerations:

- Pathway Interconnectivity: Multiple signaling pathways (kisspeptin-GPR54, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, inflammation-related pathways) form interconnected networks [35].

- Neurological Components: Functional neuroimaging reveals central nervous system contributions to reproductive disorders [35].

- Hormonal Dynamics: Consider cyclical hormonal fluctuations and feedback mechanisms in the HPO axis [35].

Table 3: Key Signaling Pathways in Reproductive Disorders and Their Therapeutic Implications

| Pathway | Role in Reproductive Axis | Associated Disorders | Potential Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kisspeptin-GPR54 | Upstream regulator of GnRH pulse generator [35] | PCOS, Hypothalamic Amenorrhea [35] | Kisspeptin analogs/antagonists, flavonoid modulation [35] |

| PI3K/Akt/mTOR | Ovarian function, follicular development, energy sensing [35] | PCOS, Ovarian Aging [35] | Plant polyphenols (resveratrol, curcumin) [35] |

| BDNF-TrkB | Neuroplasticity, emotional regulation, local ovarian function [35] | PCOS, Endometriosis, Menopausal Symptoms [35] | Ginsenoside Rg1, Ginkgolide B [35] |

| NF-κB | Inflammation-immune-reproductive system bridge [35] | Endometriosis, PCOS [35] | Tanshinone, Tetramethylpyrazine [35] |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Omics Pathway Analysis in Reproductive Disorders

This protocol describes an integrated approach to identify therapeutic targets in complex reproductive disorders using multi-omics data and functional validation.

Materials:

- Patient tissue samples (endometrial, ovarian) or blood samples

- Single-cell RNA sequencing platform

- Spatial transcriptomics reagents

- Functional MRI access (for neuroendocrine studies)

- Primary cell culture equipment

- Pathway analysis software (Ingenuity IPA, Metacore)

- qPCR reagents and equipment

- Western blot apparatus and antibodies for target proteins

Procedure:

Patient Stratification and Sample Collection

- Recruit well-phenotyped patient cohorts using standardized diagnostic criteria

- Collect tissue biopsies (endometrial, ovarian) during specific menstrual cycle phases (confirmed by ultrasound and hormonal assays)

- Process samples immediately for single-cell suspension or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen

- Collect peripheral blood for hormone level quantification (FSH, LH, estradiol, progesterone, testosterone)

Multi-Omics Profiling

- Perform single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) on 10,000-20,000 nuclei per sample using 10X Genomics platform

- Conduct spatial transcriptomics on OCT-embedded tissue sections to maintain architectural context

- Analyze DNA methylation patterns using whole-genome bisulfite sequencing in relevant cell populations

- For neuroendocrine components, perform resting-state fMRI to assess functional connectivity in brain regions regulating reproductive function

Computational Integration and Pathway Identification

- Cluster snRNA-seq data using Seurat or Scanpy to identify cell subpopulations

- Perform differential expression analysis between patient and control groups within each cell type

- Integrate spatial transcriptomics data to map dysregulated pathways to tissue microenvironments

- Conduct gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and pathway overrepresentation analysis using KEGG, Reactome, and WikiPathways databases

- Construct regulatory networks using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

Functional Validation of Candidate Targets

- Culture primary human granulosa cells or endometrial stromal cells in phenol-red free media with charcoal-stripped FBS

- Modulate candidate targets using siRNA knockdown (10-50nM), pharmacological inhibitors, or CRISPR inhibition (dCas9-KRAB)

- Assess functional outcomes: steroid hormone production (ELISA), cell proliferation (MTS assay), apoptosis (Annexin V staining), inflammatory cytokine secretion (Luminex)

- Validate pathway modulation by western blot for phosphorylated signaling intermediates

Translational Assessment

- Examine expression conservation of validated targets in existing animal models

- Assess druggability using databases like DrugBank and CanSAR

- Evaluate potential for repurposing existing therapeutics with known safety profiles

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Target Identification Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Editors | ABE8e, BE4max [33] | Point mutation correction without DSBs | ABE for A•T>G•C; CBE for C•G>T•A conversions [33] |

| CRISPR Nucleases | SpCas9, eSpCas9(1.1), Cas12a [37] | Gene disruption, HDR-mediated correction | High-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects [37] |

| Delivery Systems | AAV serotypes, LNPs, Electroporation [37] [39] | Editor component delivery to target cells | LNP preferred for in vivo delivery; AAV for sustained expression [39] |

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10X Genomics Chromium, Parse Biosciences | Cell-type specific profiling in heterogeneous tissues | Preserves cellular heterogeneity lost in bulk analyses [40] |

| Pathway Modulators | Kisspeptin analogs, NK3R antagonists, Resveratrol [35] [36] | Target validation in reproductive axis | Multi-target approaches often required for complex disorders [35] |

| Stem Cell Models | Patient-derived iPSCs, Organoid systems [34] [40] | Disease modeling and therapeutic testing | Enables study of human-specific biology without animal models [40] |

| TLR7/8 agonist 4 TFA | TLR7/8 agonist 4 TFA, MF:C20H25F3N6O2, MW:438.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Br-DAPI | Br-DAPI, MF:C16H14BrN5, MW:356.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The strategic approach to identifying therapeutic targets differs fundamentally between monogenic diseases and complex reproductive disorders. Monogenic conditions benefit from precisely defined genetic targets and direct correction approaches using advanced gene editing tools like base editors, which can theoretically correct approximately 95% of pathogenic transition mutations [33]. In contrast, complex reproductive disorders require systems-level analyses of dysregulated pathways within the neuroendocrine-reproductive axis, often necessitating multi-target intervention strategies [35].

Successful therapeutic development in both domains will continue to leverage advancing technologies—from next-generation CRISPR systems with enhanced specificity to multi-omics integration platforms that can deconvolute complex disease pathophysiology. Researchers should select their target identification and validation strategies based on this fundamental distinction in disease etiology and the corresponding methodological requirements outlined in this application note.

The application of gene editing technologies to correct reproductive genetic abnormalities represents one of the most promising yet ethically complex frontiers in modern medicine. The distinction between therapeutic intervention and human enhancement forms the critical boundary in this discourse, though this line is often blurred and poorly defined in practice [41]. While gene editing for disease prevention aims to restore health by correcting mutations responsible for heritable disorders, enhancement seeks to improve human capabilities beyond typical functioning, raising profound ethical concerns about equity, human dignity, and the future of our species [41] [42].

The global scientific community maintains a strong consensus that clinical application of germline gene editing remains ethically impermissible at present, though careful basic research is encouraged [24] [43]. However, recent years have witnessed a resurgence of interest from private companies and investors seeking to advance this technology, intensifying the urgency for robust ethical frameworks [24] [44]. This application note examines the current ethical landscape and provides technical protocols for responsible research in reproductive genetic interventions.

Current Ethical Frameworks and Guidelines

International approaches to governing human genomic enhancement (HGE) have evolved through distinct stages, moving from typological distinctions toward more nuanced welfare-based considerations [41].

Evolution of Ethical Governance

Table 1: Chronological Development of Ethical Guidelines for Human Genomic Enhancement

| Time Period | Regulatory Approach | Key Features | Representative Policies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-2017 | Typological Differentiation | Distinction between somatic/germline editing; therapy/enhancement | German scientific agencies' statement (2015); FEAM position paper (2017) |

| 2018-Present | Welfare-Based Considerations | Focus on human welfare and social consequences; precautionary principle | Nuffield Council of Bioethics reports; Chinese ethical framework proposals |

| Future Directions | Collaborative Governance | Multi-stakeholder engagement; independent ethics review | Regional ethics review centers; public deliberation processes |

Initial ethical standards centered on differentiating between somatic versus germline gene enhancement and between gene editing for enhancement versus therapy [41]. This approach implied that genetic interventions should only proceed for therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive purposes without altering the genome of future generations. More recent frameworks have begun to challenge this dichotomous thinking, recognizing that the concept of "normal" varies across social contexts and that the field of medicine has progressively expanded to include preventive, palliative, and fertility-related procedures that defy simple categorization [41].

Proposed Ethical Framework for Reproductive Genetic Applications

Based on analysis of current literature, we propose an integrated ethical framework for gene editing in reproductive genetics with three core components:

Application of the Precautionary Principle: This serves as an overarching benchmark, emphasizing caution in the face of uncertain risks and potential irreversible consequences for future generations [41].

Multi-Stakeholder Collaborative Governance: This model promotes engagement and dialogue among scientists, ethicists, policymakers, and the public to ensure diverse perspectives inform development and regulation [41].

Regional Ethics Review Centers: Independent review processes provide oversight and maintain public trust through transparent evaluation of research proposals [41].

This framework aims to balance scientific innovation with necessary safeguards, particularly important given the rapid commercialization of gene editing technologies and concerns about unequal access potentially exacerbating social stratification [42].

Technical Protocols for Gene Editing Research

CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow for Embryonic Gene Editing

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene editing in embryonic research, integrating both technical and ethical considerations:

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Embryonic Gene Editing Workflow

CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism and DNA Repair Pathways

The molecular mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 involves precise targeting and cleavage of DNA sequences, followed by cellular repair processes that enable genetic modifications:

Diagram 2: CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism and DNA Repair Pathways

The CRISPR-Cas9 system creates double-stranded breaks in DNA that are repaired through either Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) or Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathways [45]. NHEJ typically results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, while HDR enables precise genetic corrections when a donor template is provided [46] [45].

Optimization and Validation Protocols

Transfection Optimization

Successful CRISPR editing requires extensive optimization of transfection parameters. Research indicates that approximately 87% of CRISPR researchers incorporate optimization steps in their workflows, testing an average of seven different conditions [47]. Key recommendations include:

- Cell Line Specificity: Optimization should be performed using the target cell line rather than surrogates, as editing efficiency varies significantly across cell types [47].

- Positive Controls: Include species-specific positive controls to distinguish between guide RNA failures and parameter optimization issues [47].

- Editing Efficiency vs. Cell Viability Balance: Aim for conditions that provide sufficient editing efficiency without excessive cell death [47].

Advanced optimization approaches can test up to 200 conditions in parallel using automated platforms, significantly increasing editing efficiency compared to standard protocols [47].

Off-Target Analysis

Comprehensive off-target analysis is essential for assessing safety in reproductive genetic applications. The PRIDICT tool, developed through interdisciplinary collaboration, uses artificial intelligence to predict prime editing outcomes and optimize guide RNA design, addressing concerns about unintended genomic alterations [43].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reproductive Gene Editing Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes | Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex | Enables precise DNA cleavage at target sites | Direct delivery of preassembled RNP complex reduces off-target effects; superior to plasmid DNA transfection | Requires stringent handling protocols for embryonic applications |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci | Design multiple gRNAs (3-4) per target; validate with PRIDICT or similar AI tools | Target selection must align with therapeutic purpose (disease prevention) |

| Base Editors | Enables direct base conversion without double-stranded breaks | Reduced indel mutations compared to standard CRISPR-Cas9; useful for precise single-nucleotide changes | Enhanced precision may raise enhancement concerns; requires ethical review |

| Prime Editors | Allows precise insertions, deletions, and substitutions | Versatile editing with minimal off-target effects; requires specialized guide RNA design | Potential for more extensive genetic modifications necessitates oversight |

| Embryo Culture Media | Supports embryonic development post-editing | Formulation affects viability and development rates; use validated media only | Limited culture periods per regulatory guidelines (typically 14 days) |

| Off-Target Assessment Tools | Detects unintended genetic modifications | Employ multiple methods (e.g., GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq); required for safety evaluation | Full transparency in reporting off-target effects is ethically mandatory |

Interdisciplinary Collaboration Framework

Responsible advancement of reproductive gene editing requires structured collaboration across disciplines. Research indicates that successful interdisciplinary projects incorporate several key strategies [43]:

- Realistic Expectations: Acknowledge the challenges of integrating diverse methodologies and perspectives from ethics, law, sociology, and biology.

- Shared Goals: Establish common objectives that bridge disciplinary boundaries while respecting different value systems.

- Regular Communication: Maintain scheduled meetings (e.g., six per year) to unite all project members and facilitate knowledge exchange.

- Expert and Lay Dialogue: Engage with citizen advisory panels to incorporate public perspectives and concerns [43].

This approach fosters checks and balances within science and can prevent unethical practices while promoting socially relevant research outcomes [43].

Gene editing for correcting reproductive genetic abnormalities holds tremendous promise for preventing devastating heritable diseases, but requires careful navigation of the ethical boundaries between therapy and enhancement. The framework presented in this application note emphasizes safety, transparency, and multi-stakeholder oversight as essential components of responsible research.