Microbiome-Immune Crosstalk in Reproductive Health: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Translation

This review synthesizes current research on the dynamic interactions between the reproductive tract microbiome and the host immune system, a field rapidly advancing our understanding of female physiology and pathology.

Microbiome-Immune Crosstalk in Reproductive Health: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Translation

Abstract

This review synthesizes current research on the dynamic interactions between the reproductive tract microbiome and the host immune system, a field rapidly advancing our understanding of female physiology and pathology. We explore foundational concepts of microbial composition and spatial distribution from the vagina to the endometrium, detailing mechanistic pathways through which microbiota regulate immune homeostasis and inflammation. The article critically evaluates methodological approaches, omics technologies, and emerging microbiome-based therapeutic strategies for conditions like recurrent pregnancy loss, implantation failure, and endometriosis. By integrating foundational knowledge with applied clinical challenges and validation frameworks, this resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive roadmap for translating microbiome-immune interactions into novel diagnostics and therapeutics.

Mapping the Landscape: Core Principles of Reproductive Tract Microbiomes and Immune Dialogue

The human reproductive tract features a complex, spatially organized microbiome, with compositional and functional niches that critically influence mucosal immunology and reproductive health. Once considered sterile, the upper reproductive tract is now recognized to host a low-biomass but metabolically active microbial community distinct from the vaginal ecosystem [1]. The spatial distribution of these microbes—from the Lactobacillus-dominated vagina to the more diverse endometrial environment—forms a physiological gradient that interacts with host immune responses through metabolic, inflammatory, and barrier integrity pathways [2] [3]. Disruptions to this spatial architecture are increasingly implicated in diverse gynecological pathologies, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and reduced success in assisted reproductive technologies [4] [1] [5]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the spatial organization of the reproductive tract microbiome, its functional immunology, and advanced methodologies for its investigation, providing a technical framework for researchers and therapeutic developers.

Spatial Distribution of Microbiome in the Reproductive Tract

Lower Reproductive Tract: Vaginal Community State Types

The vaginal microbiome represents the most well-characterized microbial niche in the female reproductive system. In healthy reproductive-aged women, it is typically characterized by low diversity and dominance of Lactobacillus species, which maintain a protective acidic environment (pH 3.5-4.5) through lactic acid production [2] [6]. Culture-independent sequencing approaches have categorized the vaginal microbiota into five primary Community State Types (CSTs), each with distinct spatial and functional characteristics [2].

Table 1: Vaginal Community State Types (CSTs) and Their Characteristics

| Community State Type | Dominant Taxa | pH | Stability | Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CST-I | Lactobacillus crispatus | ≤4.5 | High | Optimal health; reduced STI/HIV risk; higher IVF success [6] [7] |

| CST-II | Lactobacillus gasseri | ≤4.5 | Moderate | Generally healthy |

| CST-III | Lactobacillus iners | ≤4.5 | Low | Transition state; associated with BV onset [2] |

| CST-V | Lactobacillus jensenii | ≤4.5 | Moderate | Generally healthy |

| CST-IV | Diverse anaerobes (Gardnerella, Prevotella, Atopobium) | >4.5 | Variable | Bacterial vaginosis; inflammation; reduced fertility; increased HIV risk [3] [4] |

L. iners (CST-III) presents a unique case of a Lactobacillus species with potential pathogenic traits. Its reduced genome size (~1.3 Mb versus 1.5-2.0 Mb for other lactobacilli) indicates limited metabolic capacity and loss of genes for D-lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide production [2]. Furthermore, L. iners expresses inerolysin, a pore-forming toxin that may compromise mucosal integrity, facilitating dysbiosis and ascending infection [2].

Upper Reproductive Tract: Endometrial Microbiome

The endometrial microbiome exists as a low-biomass community (approximately 100-10,000 times less abundant than vaginal microbiota) that exhibits taxonomic and functional profiles distinct from the vaginal niche [1]. A Lactobacillus-dominant composition in the endometrium correlates with reproductive success, whereas dysbiosis characterized by increased microbial diversity and enrichment of anaerobic taxa (Gardnerella, Streptococcus, Prevotella) associates with chronic endometritis, implantation failure, and adverse IVF outcomes [1].

Table 2: Comparative Features of Reproductive Tract Microbiome Niches

| Parameter | Vaginal Niche | Endometrial Niche |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass | High | Low (100-10,000x lower than vagina) [1] |

| Dominant Taxa in Health | Lactobacillus spp. (CSTs I, II, III, V) | Lactobacillus spp. |

| Diversity in Health | Low | Low |

| Characteristic pH | 3.5-4.5 [2] | Not well characterized |

| Sampling Challenges | Minimally invasive; self-sampling possible | Invasive procedures (biopsy, aspirate); high contamination risk [1] |

| Key Functions | Lactic acid production; pathogen exclusion; immunomodulation | Embryo implantation support; immunotolerance; endometrial receptivity [1] |

Immunological Interactions of the Spatial Microbiome

Mucosal Barrier Integrity and Immune Homeostasis

The spatially restricted microbiomes engage in dynamic crosstalk with host immune cells through metabolic products, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and cytokine networks. In the lower reproductive tract, Lactobacillus dominance maintains barrier integrity through lactic acid production and bacteriocin secretion [2]. Spatial transcriptomics of ectocervical tissue reveals that a Lactobacillus crispatus/acidophilus-dominated microbiome associates with gene signatures involved in active immune engagement and mucosal barrier integrity, while highly diverse microbiomes associate with altered expression of genes involved in epithelial maintenance and immune function throughout the mucosal layers, not just at the luminal surface [3].

Dysbiosis-Induced Inflammatory Pathways

Vaginal dysbiosis (CST-IV) triggers a cascade of inflammatory events through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Anaerobic bacteria produce biogenic amines (putrescine, cadaverine) and enzymes (sialidases) that degrade mucins, compromise epithelial integrity, and elevate vaginal pH [2]. Microbial translocation activates pattern recognition receptors (TLRs) on epithelial and immune cells, triggering NF-κB signaling and pro-inflammatory cytokine production (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) [2]. This inflammatory milieu recruits neutrophils and activates endocervical antigen-presenting cells, further amplifying immune activation [2].

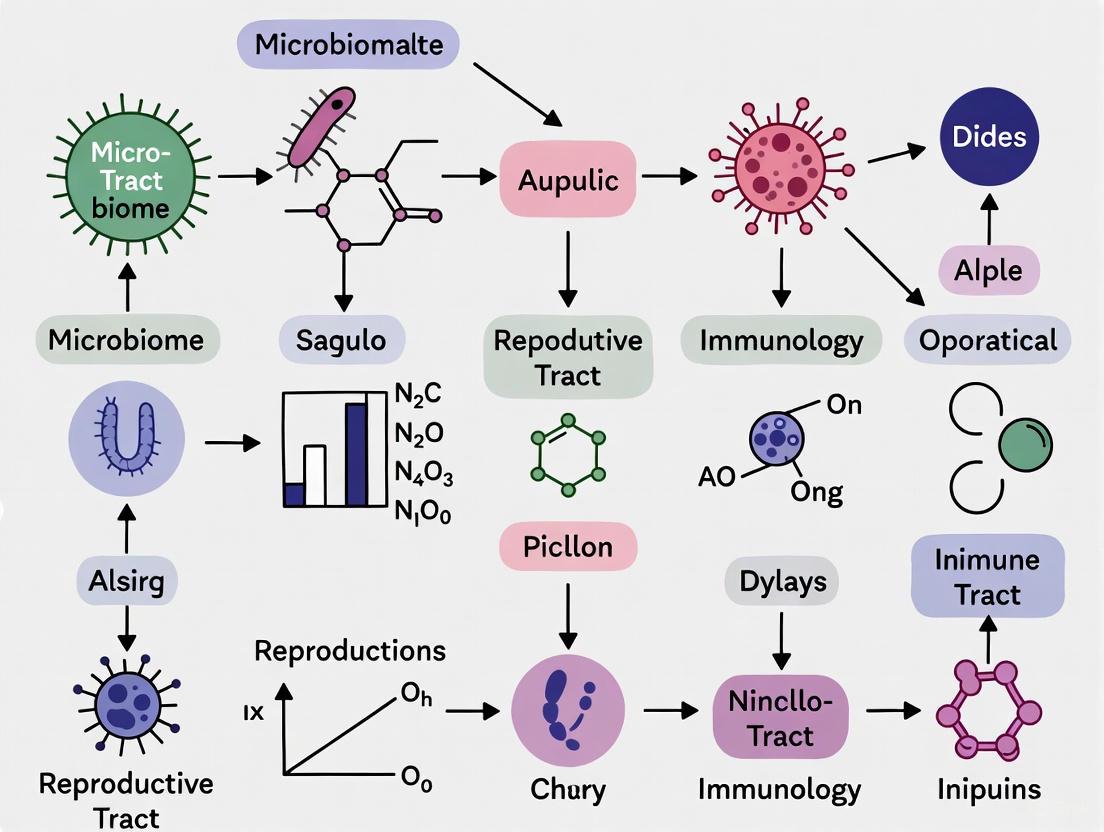

Diagram 1: Dysbiosis-induced inflammation pathway. CST-IV anaerobes trigger barrier damage and NF-κB-mediated inflammation.

Systemic Immunological Consequences

The immunological impact of reproductive tract dysbiosis extends beyond local inflammation. In endometrial cancer, dysbiosis contributes to a tumor-promoting microenvironment characterized by chronic inflammation, altered cytokine signaling, and immune evasion [8]. Similarly, in recurrent pregnancy loss and repeated implantation failure, dysbiosis disrupts the delicate immunotolerance required for embryo implantation and maintenance, involving imbalances in T-cell populations (Th1/Th2/Th17) and natural killer cell function [4].

Methodological Approaches for Spatial Microbiome Analysis

Sampling Protocols and Contamination Control

Research into the spatial architecture of the reproductive tract microbiome requires stringent methodologies to address the challenge of low biomass, particularly in endometrial sampling.

- Sample Collection: Endometrial samples obtained via biopsy, swab, or aspirate during hysterectomy or transcervical procedures risk contamination from cervical/vaginal microbiota [1]. The use of uterine manipulators and cervical dilators may further contribute to cross-contamination.

- Contamination Mitigation: Essential practices include processing samples in DNA-/RNA-free environments, including negative control samples (collection reagents without tissue), and using DNA extraction kits designed for low-biomass samples [1].

- Sample Quality Assessment: RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥7 is recommended for transcriptomic analyses, as used in spatial transcriptomics studies of ectocervical tissue [3].

Genomic and Transcriptomic Technologies

Table 3: Analytical Methods for Reproductive Tract Microbiome Research

| Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Sequencing | Amplification and sequencing of hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene | Taxonomic profiling; CST classification [6] | Cost-effective; well-established bioinformatics pipelines | Limited taxonomic resolution (species/strain level); PCR amplification biases [1] |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | Untargeted sequencing of all DNA in a sample | Taxonomic profiling at species/strain level; functional potential analysis [1] | Higher resolution; functional inference | Higher cost; computationally intensive; host DNA contamination [1] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Genome-wide mRNA sequencing with spatial localization | Host gene expression mapping in tissue architecture; host-microbiome interactions [3] | Preserves tissue architecture; identifies spatially restricted gene expression [3] | Requires high RNA quality; limited microbial transcript detection |

| Metabolic Modeling | In silico reconstruction of metabolic networks from genomic data | Prediction of metabolic fluxes; host-microbiome metabolic interactions [9] | Provides mechanistic insights; integrates multi-omics data | Computationally intensive; model quality depends on genome annotation |

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow

Diagram 2: Multi-omics workflow for spatial microbiome analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reproductive Tract Microbiome Studies

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina (16S, shotgun metagenomics); PacBio (long-read) | Microbial profiling; metagenomic assembly [6] | Long-read sequencing improves assembly of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [9] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10x Genomics Visium | Spatial host gene expression analysis [3] | 55μm spot diameter captures 1-10 cells; requires RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥7 [3] |

| Metabolic Modeling | gapseq; Recon (host metabolic models) | Metabolic network reconstruction; prediction of community interactions [9] | Enables prediction of metabolic dependencies and metabolite exchange |

| Data Visualization & Analysis | Cellxgene; Spotfire; Phantasus; Polly Platform | Exploration of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data [10] | Custom Shiny applications enable interactive data exploration [10] |

| Cell Culture Models | 3D endometrial organoids | Functional validation of host-microbiome interactions [1] | Provides physiologically relevant context for mechanistic studies |

| Penicillin G | Penicillin G | Research-grade Penicillin G, a beta-lactam antibiotic. For microbiological & biochemical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Amidosulfuron | Amidosulfuron | Sulfonylurea Herbicide | RUO | Amidosulfuron is a sulfonylurea herbicide for plant biology research. It inhibits acetolactate synthase (ALS). For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The spatial architecture of the reproductive tract microbiome—from vaginal CSTs to endometrial niches—represents a critical determinant of reproductive health and disease. The integration of advanced methodologies including spatial transcriptomics, metabolic modeling, and multi-omics integration provides unprecedented insight into the functional relationships between spatially restricted microbial communities and host immunology. Future research directions should focus on establishing standardized protocols for low-biomass microbiome analysis, developing novel in vitro models to dissect mechanism of action, and translating ecological understanding into targeted therapeutic interventions that preserve or restore beneficial microbial niches across the reproductive tract continuum.

The female reproductive tract (FRT) microbiome is a critical component of reproductive health, functioning as a dynamic interface between host physiology and the external environment. Within the context of reproductive tract immunology, a healthy microbiome is not merely defined by the absence of pathogens but by specific, measurable hallmarks that maintain immunological homeostasis and support key reproductive processes including embryo implantation, placentation, and pregnancy maintenance [4] [11]. Disruption of these core hallmarks—Lactobacillus dominance, specialized metabolic function, and barrier integrity—triggers fundamental shifts in immune responses that are increasingly implicated in adverse reproductive outcomes such as recurrent implantation failure (RIF), recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), and preterm birth [4] [12]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to delineate the definitive characteristics of a healthy FRT microbiome and their interplay with local and systemic immunity, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Core Hallmarks of a Healthy Reproductive Tract Microbiome

Lactobacillus Dominance and Community State Stability

The most prominent feature of a healthy vaginal and upper reproductive tract microbiome is its dominance by bacteria from the genus Lactobacillus. This dominance is quantitatively defined, with lactobacilli typically constituting over 70% and often exceeding 90% of the microbial population in healthy states [11] [13]. This low-diversity ecosystem is categorized into specific Community State Types (CSTs), with CST-I (L. crispatus), CST-II (L. gasseri), CST-III (L. iners), and CST-V (L. jensenii) representing Lactobacillus-dominated healthy states [2] [14]. In contrast, CST-IV is characterized by a marked reduction in Lactobacillus and increased diversity of anaerobic bacteria, a signature of dysbiosis associated with bacterial vaginosis and adverse reproductive outcomes [2] [12].

Table 1: Key Lactobacillus Species in the Healthy Female Reproductive Tract

| Lactobacillus Species | Dominant Community State Type | Key Functional Attributes | Immunological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. crispatus | CST-I | High D-lactic acid production, Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production [2] | Strong barrier enhancement, anti-inflammatory [2] |

| L. gasseri | CST-II | Lactic acid production [2] | Maintains low pH, pathogen exclusion [11] |

| L. iners | CST-III | L-lactic acid only, limited metabolism, produces inerolysin [2] | Unstable, associated with transition to dysbiosis [2] |

| L. jensenii | CST-V | Lactic acid production [2] | Maintains healthy microenvironment [11] |

It is crucial to note that not all Lactobacillus species confer equal protective benefits. L. iners, despite being a dominant species in CST-III, possesses a reduced genome size (~1.3 Mb) and lacks the ability to produce D-lactic acid or hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), key antimicrobial compounds generated by other lactobacilli [2]. Furthermore, its genome encodes for the pore-forming toxin inerolysin, which may compromise the vaginal mucus layer [2]. This functional deficiency positions L. iners as a transitional species that may facilitate the shift to the dysbiotic CST-IV state rather than robustly maintaining homeostasis [2].

Metabolic Function and Acidic pH Maintenance

A defining functional hallmark of a healthy FRT microbiome is a specialized metabolism centered on lactic acid production. Lactobacilli metabolize glycogen derived from vaginal epithelial cells, fermenting it to produce copious amounts of lactic acid (both D and L isoforms) [2] [11]. This process maintains the vaginal environment at a low pH, typically ranging from 3.5 to 4.5, which directly inhibits the growth of pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria [2] [11]. The acidic environment is a primary immune-modulatory factor, as many pro-inflammatory pathogens are unable to thrive under these conditions.

Beyond its role in acidification, lactic acid itself possesses direct immunomodulatory properties. It influences the function of immune cells, including macrophages and T cells, and helps maintain a state of anti-inflammatory tolerance, which is particularly critical during pregnancy to prevent rejection of the semi-allogeneic fetus [4]. Some lactobacilli, notably L. crispatus, also produce hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), which acts as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent, synergizing with host-derived defenses to control pathogen growth [2].

Table 2: Core Metabolic Functions and Outputs in a Healthy Microbiome

| Metabolic Process | Key Microbial Agents | Functional Outputs | Impact on Host Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycogen Fermentation | L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. jensenii [2] | Lactic Acid (D & L isomers) [2] | Low pH (3.5-4.5), direct pathogen inhibition [2] [11] |

| Oxidative Metabolism | Primarily L. crispatus [2] | Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [2] | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity [2] |

| Mucin Utilization | Limited in healthy state | Maintains mucin layer integrity [2] | Preserves epithelial barrier function [2] |

Epithelial Barrier Integrity

The third hallmark of a healthy microbiome is the preservation of structural and functional integrity of the cervicovaginal and endometrial epithelial barriers. A Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota reinforces this barrier through multiple mechanisms. Physically, the bacteria adhere to epithelial cells, preventing colonization by pathogens through competitive exclusion [5]. Functionally, their metabolic products, particularly lactic acid, help maintain the integrity of tight junctions between epithelial cells and support the protective mucin layer [2].

A dysbiotic microbiome, characterized by CST-IV with high diversity of anaerobes like Gardnerella, Prevotella, and Atopobium, has the opposite effect [2]. These bacteria secrete harmful metabolites such as biogenic amines (e.g., putrescine, cadaverine) and enzymes like sialidases that degrade mucins [2]. This degradation compromises the mucosal barrier, facilitating microbial translocation and exposing underlying immune cells to microbial pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [2]. This breach initiates a pro-inflammatory cascade via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), triggering the production of cytokines and chemokines that recruit lymphocytes and drive inflammation, thereby disrupting the immune tolerance required for reproductive success [4] [2].

Immunological Interactions of a Healthy Microbiome

The hallmarks of a healthy microbiome are intrinsically linked to the regulation of both innate and adaptive immunity in the FRT. The mechanistic interplay can be visualized through the following signaling pathway:

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental immunological differences between a healthy and dysbiotic state. A healthy, Lactobacillus-dominated microbiome promotes an anti-inflammatory state characterized by increased regulatory T (Treg) cells and alternatively activated (M2) macrophages, which is essential for embryo implantation and pregnancy maintenance [4]. Conversely, dysbiosis triggers a pro-inflammatory response via TLR/NF-κB signaling, leading to the production of cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-23, and promoting a Th17 response, which is linked to RIF, RPL, and other adverse outcomes [4] [2].

The vaginal microbiota can influence uterine immunity through several mechanistic pathways: 1) direct bacterial translocation due to impaired mucosal barriers, 2) systemic immune activation via soluble inflammatory mediators, and 3) modulation of cytokine and chemokine gradients that direct immune cell trafficking [4]. Furthermore, vaginal dysbiosis can activate inflammasomes, leading to the cleavage of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 and induction of pyroptosis, further amplifying local inflammation [4].

Experimental Assessment and Methodologies

Standard Analytical Workflows

Rigorous assessment of the FRT microbiome's health status requires integrated methodological approaches, from sequencing to functional assays. The standard workflow for characterization is outlined below:

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Sample Types: Vaginal swabs (mid-vaginal wall), cervical swabs, endometrial fluid/taper biopsies obtained under sterile conditions [11] [12].

- Storage: Immediate freezing at -80°C or placement in specialized stabilization buffers (e.g., Zymo Research DNA/RNA Shield) to preserve microbial community structure.

- DNA Extraction: Using commercially available kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit, Mo Bio PowerSoil Kit) optimized for low bacterial biomass samples. Protocols typically include a mechanical lysis step (bead-beating) to ensure efficient Gram-positive bacterial cell wall disruption [12].

Sequencing and Bioinformatics

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing (Targeted): Amplifies hypervariable regions (e.g., V4) for cost-effective profiling of community composition and α/β-diversity. Analysis pipelines include QIIME 2, DADA2, and mothur for amplicon sequence variant (ASV) analysis [5].

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (Untargeted): Sequences all genomic DNA in a sample, enabling species/strain-level identification and functional potential analysis via tools like MetaPhlAn for taxonomy and HUMAnN for metabolic pathways [12]. This method is critical for detecting subtle variations associated with conditions like cervical shortening and preterm birth [12].

Functional Validation Assays

- pH Measurement: Direct measurement of vaginal pH using colorimetric pH strips (range 3.6-6.5) is a rapid, clinical correlate of Lactobacillus metabolic activity [11].

- Lactic Acid Quantification: Quantified via commercial enzymatic assay kits or Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) [2].

- Cytokine Profiling: Multiplex immunoassays (Luminex xMAP technology) or ELISA to quantify pro-inflammatory (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-23) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines in cervicovaginal lavage or supernatant from epithelial cell cultures [4].

- Barrier Function Assays: Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) measurements and fluorescent dye permeability assays (e.g., FITC-dextran) using in vitro models of vaginal epithelium exposed to Lactobacillus-conditioned media versus dysbiotic pathobionts [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Microbiome-Immune Research

| Product Category/Name | Primary Function | Application in FRT Research |

|---|---|---|

| Zymo Research DNA/RNA Shield | Nucleic acid stabilization | Preserves microbial RNA/DNA integrity during sample transport/storage [12] |

| QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit | DNA extraction | Optimized for efficient lysis of Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus) [12] |

| Illumina MiSeq/NovaSeq | DNA Sequencing Platform | 16S amplicon (MiSeq) and shotgun metagenomic (NovaSeq) sequencing [12] |

| Bio-Rad Luminex xMAP Assays | Multiplex cytokine quantification | Simultaneous measurement of 30+ immune mediators in low-volume CVF samples [4] |

| Sigma-Aldrich L-Lactic Acid Assay Kit | Metabolite quantification | Enzymatic measurement of a key Lactobacillus metabolic output [2] |

| Epivaginal / VEC-100 Tissue Model | In vitro epithelial barrier | 3D model for testing barrier integrity and host-microbe interaction [2] |

| For-Met-Leu-pNA | For-Met-Leu-pNA | Protease Substrate | RUO | For-Met-Leu-pNA is a chromogenic peptide substrate for protease research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| (R)-RO5263397 | (R)-RO5263397, CAS:1357266-05-7, MF:C10H11FN2O, MW:194.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The hallmarks of a healthy female reproductive tract microbiome—Lactobacillus dominance, specialized metabolic function yielding an acidic environment, and the promotion of epithelial barrier integrity—are intrinsically linked to immunological homeostasis. These are not isolated features but function as an integrated system that maintains a non-inflammatory, tolerant immune environment conducive to successful reproduction. The disruption of any single hallmark can initiate a cascade of pro-inflammatory signaling via pathways such as TLR/NF-κB and inflammasome activation, contributing to the pathophysiology of RIF, RPL, and other gynecological conditions [4] [2]. For researchers and drug developers, these hallmarks provide a concrete set of biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Future interventions, whether probiotic, postbiotic, or immunomodulatory, must be evaluated against their ability to restore this triad of core functions. Advancing our understanding of this complex interplay will be pivotal in developing novel, effective strategies to improve reproductive outcomes across diverse patient populations.

Vaginal microbiome dysbiosis represents a significant departure from a healthy, Lactobacillus-dominated ecosystem, profoundly influencing reproductive tract immunology and clinical outcomes. The concept of Community State Types (CSTs) provides a fundamental framework for classifying vaginal microbial communities, where CSTs I, II, III, and V are dominated by L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners, and L. jensenii, respectively [15] [16]. In contrast, CST-IV is defined by a marked decrease in Lactobacillus species and an increase in microbial diversity, encompassing a polymicrobial consortium of facultative and obligate anaerobes [17] [2]. This state is frequently linked to bacterial vaginosis (BV), aerobic vaginitis, and an elevated risk of adverse reproductive health outcomes, including preterm birth and increased susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections [18] [19]. Within this dysbiotic environment, the expansion of pathobionts—commensal microorganisms with pathogenic potential—adds a critical layer of complexity to host-microbe interactions, often triggering pronounced inflammatory responses [20] [19]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of CST-IV architecture, the dynamics of pathobiont expansion, and the resultant immunological perturbations, offering a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of microbiome science and reproductive immunology.

Community State Type IV (CST-IV): Architecture and Subtypes

CST-IV is not a monolithic entity but a heterogeneous state characterized by substantial microbial diversity and the absence of Lactobacillus dominance. Its definition has been refined to include several distinct subtypes, each with unique taxonomic and clinical profiles.

Subtype Classification and Microbial Composition

Advanced sequencing studies have delineated CST-IV into specific subtypes, providing a finer resolution of its architectural framework.

- CST IV-A: This subtype is characterized by a high abundance of Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae (BVAB1) and moderate abundances of Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, and Prevotella species [16] [2]. These species are recognized as pro-inflammatory and are strongly implicated in the development of bacterial vaginosis [16].

- CST IV-B: Distinguished by a high abundance of Gardnerella vaginalis alongside Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae, Atopobium vaginae, and Prevotella [16]. The collaboration between G. vaginalis and other disruptive bacteria creates an environment conducive to BV [16].

- CST IV-C: A broader subtype further partitioned into microbiologically distinct subgroups [17] [16]:

- IV-C0: Moderate abundance of Prevotella, including species like Prevotella bivia linked to BV and pelvic inflammatory disease [16].

- IV-C1: High abundance of Streptococcus species. While some streptococci produce lactic acid, Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Strep) is a significant pathobiont in pregnancy [16].

- IV-C2: Dominated by Enterococcus species, associated with aerobic vaginitis and urinary tract infections [17] [16].

- IV-C3: Features a high level of Bifidobacterium species, which produce lactic acid and can lower vaginal pH, offering some protection [16].

- IV-C4: High abundance of Staphylococcus species, also linked to aerobic vaginitis [17] [16].

Table 1: Characteristics of CST-IV Subtypes and Associated Pathobionts

| CST-IV Subtype | Dominant / Signature Taxa | Key Pathobionts Frequently Associated | Common Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV-A | Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae, Gardnerella vaginalis | Prevotella spp. | Bacterial Vaginosis [16] |

| IV-B | Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae | Prevotella spp. | Bacterial Vaginosis [16] |

| IV-C0 | Prevotella spp. | Prevotella bivia | Pelvic Inflammatory Disease [16] |

| IV-C1 | Streptococcus spp. | Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS) | Neonatal infections [16] |

| IV-C2 | Enterococcus spp. | Enterococcus faecalis | Aerobic Vaginitis, UTI [17] [16] |

| IV-C3 | Bifidobacterium spp. | (Generally protective) | Lower vaginal pH [16] |

| IV-C4 | Staphylococcus spp. | Staphylococcus aureus | Aerobic Vaginitis [17] [16] |

Epidemiological Distribution of CST-IV

The prevalence and stability of CST-IV are influenced by ethnic and geographical factors. While Lactobacillus dominance is common in Caucasian and Asian women, CST-IV is more frequently observed among women of African, Hispanic, and certain Asian ancestries, where it may represent a common and stable vaginal community state rather than a transient dysbiosis [17] [2]. A study of a diverse intercontinental cohort (N=151) found that Lactobacillus spp. dominated in 91.8% of African American women, but in significantly lower proportions in European (German, 42.4%), Asian (Indonesian, 45.0%), African (Kenyan, 34.4%), and Afro-Caribbean (26.1%) women, with the latter groups showing a higher prevalence of CST-IV and other non-Lactobacillus dominant CSTs [17]. This suggests that host genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors collectively shape the propensity for CST-IV.

Pathobiont Expansion in the Dysbiotic Vaginal Niche

Pathobionts are commensal microorganisms that can exploit perturbations in the host microbiome and immune system to expand and exert pathogenic effects, often triggering inflammation and tissue damage [20] [19].

Defining the Vaginal Pathobiont Landscape

A meta-analysis of 2,044 samples identified 40 pathobiont taxa, with six non-minority genera being most prevalent: Streptococcus (accounting for 54% of pathobiont reads), Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Escherichia/Shigella, Haemophilus, and Campylobacter [19]. When combined, the vaginal microbiota of 17% of women contained a pathobiont relative abundance of at least 1% [19]. These pathobionts are clinically significant for their roles in maternal and neonatal infections (e.g., Group B Streptococcus), pelvic inflammatory disease, and potentially more severe inflammatory vaginitis syndromes [19].

Ecological Dynamics and Inflammatory Potential

The expansion of pathobionts within the vaginal ecosystem is governed by distinct ecological relationships.

- Correlation with BV-anaerobes: A significant positive correlation exists between the estimated concentrations of pathobionts and BV-anaerobes (r = 0.1938), indicating that pathobionts often co-occur and expand in dysbiotic environments characterized by high anaerobic bacterial load [19].

- Lack of correlation with Lactobacillus: There is no significant correlation between the estimated concentrations of pathobionts and lactobacilli (r = 0.0436), suggesting that pathobionts can persist even in Lactobacillus-dominant environments [19]. However, their relative abundances are negatively correlated (Ï = -0.9234 for lactobacilli and BV-anaerobes), meaning that as lactobacilli decrease, the overall microbial community becomes more diverse, allowing pathobionts to represent a larger fraction of the population [19].

- Inflammatory Profile: Pathobionts are notable for their high pathogenic potential. For instance, Staphylococcus aureus can trigger toxic shock syndrome, and Escherichia coli is associated with severe urinary tract and ascending infections [19]. Their presence, even at low relative abundances, can be clinically consequential.

Table 2: Key Vaginal Pathobionts and Their Clinical Implications

| Pathobiont Taxon | Reported Relative Abundance | Associated Clinical Conditions | Postulated Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus spp. | 54% of all pathobiont reads [19] | Neonatal sepsis, pelvic inflammatory disease [19] | Immune evasion, biofilm formation [16] |

| Staphylococcus spp. | Common (Specific % not detailed) | Aerobic vaginitis, toxic shock syndrome [16] [19] | Superantigen production (TSST-1) [19] |

| Enterococcus spp. | Common (Specific % not detailed) | Aerobic vaginitis, urinary tract infections [17] [16] | Epithelial adhesion, biofilm formation [17] |

| Escherichia/Shigella | Common (Specific % not detailed) | Urinary tract infections, ascending infection [19] | LPS-induced inflammation, epithelial invasion [19] |

| Mycoplasma hominis | (Correlates with BV) | Bacterial vaginosis, adverse pregnancy outcomes [17] | Synergy with Gardnerella & Prevotella (r=0.46) [17] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Host Immune Interactions

The transition to a CST-IV state and the expansion of pathobionts initiate a cascade of molecular events that disrupt vaginal homeostasis and provoke host immune responses.

Metabolic and Functional Shifts in Dysbiosis

A healthy, Lactobacillus-dominated vagina is characterized by glycogen fermentation producing D- and L-lactic acid, maintaining a low pH (≤4.5) that inhibits pathogens [2]. In CST-IV, this metabolic profile shifts dramatically. Anaerobes deplete lactic acid and produce biogenic amines (e.g., putrescine, cadaverine) and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like succinate, which elevate vaginal pH above 4.5 [18] [2]. These amines and SCFAs can exhibit pro-inflammatory properties and directly inhibit the growth of remaining lactobacilli, perpetuating dysbiosis [18] [2]. Furthermore, bacteria such as G. vaginalis and Prevotella produce sialidases and other hydrolytic enzymes that degrade the protective mucin layer of the cervicovaginal epithelium, compromising barrier integrity [2].

Immunological Signaling Pathways

The breakdown of the epithelial barrier allows microbial products to access immune pattern recognition receptors.

Diagram 1: TLR4-NF-κB Inflammatory Pathway. This pathway is activated by pathobiont-derived ligands like LPS, leading to a pro-inflammatory cascade in the vaginal mucosa [2].

Beyond the innate immune response, pathobiont antigens can polarize T-cell responses. Some pathobionts promote the differentiation of naive T cells into Th17 cells, which produce IL-17 and other cytokines that recruit neutrophils, potentially exacerbating inflammation [20]. Conversely, a dysbiotic environment may impair the function of regulatory T cells (iTregs), which are critical for maintaining immune tolerance and preventing excessive inflammation [20].

Experimental Models and Research Methodologies

Research into vaginal dysbiosis relies on a suite of well-defined experimental protocols for characterizing the microbiome and host environment.

Core Microbiome Profiling Protocol (16S rRNA Gene Sequencing)

This is the foundational method for determining CSTs and identifying pathobionts.

- Sample Collection: Vaginal swabs are collected from the posterior fornix using standardized, DNA-free swabs. Samples are immediately frozen at -80°C to preserve microbial integrity [21].

- DNA Extraction: Total genomic DNA is extracted from samples using commercial kits, such as the InstaGene Matrix or similar [17] [21].

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplification: The hypervariable V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene is amplified using broad-range primers (e.g., 515F: 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′ and 806R: 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) [17] [21].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Amplified products are purified, quantified, and sequenced on high-throughput platforms like the Illumina MiSeq system [17].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Processing: Use QIIME 2 with the DADA2 plugin to denoise, merge paired-end reads, and remove chimeras, resulting in amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [17].

- Taxonomy Assignment: Classify ASVs against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, RDP) [21].

- CST Classification: Assign CSTs using tools like VALENCIA (VAginaL community state typE Nearest CentroId clAssifier), which compares a sample's composition to a reference database of validated CSTs [18] [16].

Metabolomic and Multi-Omic Integration

To understand functional changes, metabolomic profiling is employed.

- Metabolite Extraction: Vaginal secretions are freeze-dried, weighed, and extracted with an organic solvent mixture (e.g., methanol:acetonitrile:water = 1:1:1) [21].

- Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry: Extracts are analyzed using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), typically in untargeted mode to capture a wide array of metabolites [21].

- Data Integration: Correlate metabolite abundances (e.g., SCFAs, biogenic amines) with microbial taxa and clinical inflammatory markers (e.g., systemic immune-inflammation index - SII) to build a multi-omics network of dysbiosis [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Vaginal Dysbiosis Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Product / Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality microbial genomic DNA from vaginal swabs. | InstaGene Matrix (Bio-Rad) [17]; Commercial kits from manufacturers like Guangzhou Meiji Biotechnology [21]. |

| 16S rRNA V4 Primers | Amplification of the target gene region for sequencing. | 515F / 806R primer set [17] [21]. |

| Illumina Sequencing Platform | High-throughput sequencing of amplified libraries. | MiSeq Illumina System [17]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Processing sequencing data, taxonomy assignment, and community analysis. | QIIME 2 (with DADA2 plugin) [17]; VALENCIA Classifier [18] [16]. |

| LC-MS System | Untargeted profiling of metabolites in vaginal secretions. | Agilent or Waters LC systems coupled to a time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer [21]. |

| Nugent Score Reagents | Microbiological staining for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. | Gram stain kit (Crystal Violet, Iodine, Safranin) [18]. |

| Monoolein-d5 | Monoolein-d5, CAS:565183-24-6, MF:C21H40O4, MW:361.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Meta-Fexofenadine-d6 | meta-Fexofenadine for Research|High-Qurity RUO | Explore high-purity meta-Fexofenadine for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

The intricate patterns of vaginal dysbiosis, characterized by the architecture of CST-IV, the loss of Lactobacillus dominance, and the expansion of pathobionts, create a complex pro-inflammatory environment with significant implications for reproductive tract immunology. Understanding the specific subtypes, ecological dynamics, and underlying molecular mechanisms—particularly the activation of TLR-mediated NF-κB signaling and metabolic shifts—is paramount for advancing research and therapeutic development. The field is moving towards integrated multi-omics approaches and targeted interventions, such as Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs), designed to restore ecological balance rather than broadly eradicate bacteria [18]. Future research must continue to elucidate the cause-and-effect relationships within this complex system and translate these insights into novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to improve women's reproductive health outcomes.

The mucosal surfaces of the human body, particularly the female reproductive tract (FRT), represent critical frontiers where the host immune system engages in dynamic crosstalk with resident microbiota. This intricate interaction is governed by specialized immune sentinels, primarily Toll-like receptors (TLRs), inflammasomes, and natural killer (NK) cells, which collectively maintain homeostasis or precipitate disease when dysregulated. TLRs function as primary sensors for microbial motifs, initiating signaling cascades that orchestrate both innate and adaptive immunity. Inflammasomes, including NLRP3, NLRP1, and AIM2, serve as multiprotein complexes that process key pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 while triggering pyroptotic cell death. NK cells provide critical cytotoxic function and cytokine secretion at the maternal-fetal interface. Within the FRT microenvironment, these systems interact with commensal microorganisms, hormonal signals, and microbial metabolites to shape immunological outcomes. Dysregulation of this sophisticated interplay is increasingly implicated in reproductive pathologies including infertility, preterm birth, and endometriosis. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms, functional relationships, and experimental approaches for investigating these immune sentinels, with particular emphasis on their integrated role in reproductive tract immunology.

The human mucosal ecosystem represents a vast interface where host immunity interacts with complex microbial communities. The female reproductive tract (FRT) maintains a unique immunological niche capable of providing defense against pathogens while simultaneously supporting fetal development during pregnancy. This delicate balance is regulated through continuous dialogue between immune sentinels and the reproductive tract microbiota [22] [23].

The FRT microbiota varies significantly across anatomical locations, with the vagina characterized by low diversity and Lactobacillus dominance, while the cervix, endometrium, fallopian tubes, and ovaries harbor more diverse microbial communities [22]. These microorganisms contribute to a dynamic microenvironment where metabolites, immune components, and hormonal signals interact reciprocally [24]. Disruption of this equilibrium, termed dysbiosis, is associated with various reproductive pathologies including bacterial vaginosis, infertility, endometriosis, and preterm birth [22] [23].

Central to maintaining FRT homeostasis are three key immune sentinel systems: Toll-like receptors (TLRs) as pattern recognition receptors detecting microbial motifs; inflammasomes as intracellular signaling platforms coordinating inflammatory responses; and natural killer (NK) cells as effector lymphocytes with specialized functions in the endometrium and decidua. These systems do not operate in isolation but engage in sophisticated crosstalk with each other and with the microbiota, forming an integrated defense network at the mucosal frontier [23] [24].

Toll-like Receptors: Gatekeepers of Mucosal Immunity

TLR Signaling Mechanisms and Microbial Recognition

Toll-like receptors represent a fundamental class of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that serve as the first line of defense in the innate immune system. These transmembrane proteins are strategically expressed on various immune cells—including macrophages, dendritic cells, and NK cells—as well as non-immune cells such as epithelial cells lining the FRT [25]. TLRs recognize conserved molecular patterns associated with microorganisms (PAMPs) and endogenous damage signals (DAMPs), creating a sophisticated surveillance system at the host-environment interface [25].

The structural organization of TLRs includes an extracellular leucine-rich repeat domain responsible for ligand binding, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain that initiates downstream signaling. Among the TLR family, specific members perform specialized functions in microbial detection: TLR2 (often heterodimerizing with TLR1 or TLR6) recognizes lipoproteins and lipoteichoic acid from Gram-positive bacteria; TLR4 detects lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria through cooperation with MD-2 and CD14; TLR5 binds bacterial flagellin; while TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 localize to endosomes where they recognize viral nucleic acids [25].

Upon ligand engagement, TLRs predominantly signal through the adaptor protein MyD88, culminating in the activation of transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1, which drive the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides. Alternatively, TLR3 and TLR4 can initiate a MyD88-independent pathway via TRIF, leading to type I interferon production [25]. This sophisticated recognition system allows the host to mount context-appropriate immune responses to diverse microbial challenges in the FRT.

TLR-Microbiota Interactions in Reproductive Tract Homeostasis

In the FRT, TLRs engage in continuous dialogue with the resident microbiota, playing an indispensable role in maintaining immunological equilibrium. The composition of the reproductive tract microbiota directly influences TLR expression patterns, while TLR signaling reciprocally shapes the microbial community structure [25]. For instance, specific probiotic combinations containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium species have been shown to enhance TLR2 expression and improve epithelial barrier integrity [25].

The vaginal and cervical microbiota, typically dominated by Lactobacillus species, contributes to homeostasis through TLR-mediated mechanisms. Lactobacillus crispatus, associated with optimal reproductive health, stimulates beneficial TLR signaling pathways that enhance barrier function and immune surveillance [26]. Conversely, dysbiotic conditions characterized by depletion of lactobacilli and overgrowth of anaerobic pathogens like Gardnerella vaginalis trigger maladaptive TLR responses that can perpetuate inflammation and tissue damage [26] [24].

Table 1: TLR Signaling Pathways in Mucosal Immunity

| TLR | Microbial Ligands | Signaling Pathway | Biological Functions in FRT |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR2/TLR1 | Bacterial lipoproteins, lipoteichoic acid | MyD88/NF-κB | Epithelial barrier maintenance, IL-10 production [25] |

| TLR4 | LPS from Gram-negative bacteria | MyD88/TRIF/NF-κB | Antimicrobial peptide production, chronic inflammation in dysbiosis [25] |

| TLR5 | Bacterial flagellin | MyD88/NF-κB | Shaping microbiota composition, preventing metabolic syndrome [25] |

| TLR3 | Viral double-stranded RNA | TRIF/IRF/NF-κB | Antiviral defense, interferon production [25] |

| TLR7/8 | Viral single-stranded RNA | MyD88/IRF/NF-κB | Antiviral defense, placental immunity [23] |

| TLR9 | Bacterial CpG DNA | MyD88/NF-κB | Immune cell activation, B cell maturation [25] |

Beyond their canonical role in pathogen detection, TLRs facilitate tissue homeostasis through recognition of commensal microorganisms. The TLR2/IL-10 axis exemplifies this homeostatic function, where commensal-derived signals induce anti-inflammatory IL-10 production that constrains excessive inflammation [25]. Bacteroides fragilis, through its polysaccharide A (PSA), activates TLR2 on immune cells to generate IL-10 responses that ameliorate experimental colitis [25]. Similar mechanisms likely operate in the FRT to maintain tolerance to beneficial microbiota while preserving defensive capabilities against genuine pathogens.

Inflammasomes: Intracellular Orchestrators of Inflammation

Molecular Architecture and Activation Mechanisms

Inflammasomes represent sophisticated intracellular multiprotein complexes that serve as critical platforms for inflammatory signaling. These macromolecular assemblies typically consist of a sensor protein (often from the NOD-like receptor family), the adaptor protein ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD), and the effector enzyme caspase-1 [27]. The NLR family members feature three characteristic domains: a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain that facilitates ligand recognition, a central NACHT domain responsible for nucleotide binding and oligomerization, and an N-terminal protein-protein interaction domain (either CARD or PYD) that recruits downstream signaling components [27].

Among the best-characterized inflammasomes, NLRP3 responds to diverse stimuli including microbial toxins, extracellular ATP, and crystalline substances; NLRC4 detects bacterial flagellin and type III secretion system components; NLRP1 recognizes anthrax lethal toxin and other pathogenic insults; while AIM2 responds to cytoplasmic DNA [27]. The non-canonical inflammasome pathway involves caspase-11 in mice (caspase-4/5 in humans) which detects intracellular LPS and activates NLRP3 [27].

Inflammasome activation triggers a two-step process: first, transcription of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 occurs via NF-κB signaling; second, inflammasome assembly leads to caspase-1 activation, which cleaves the pro-forms of IL-1β and IL-18 into their biologically active forms while simultaneously inducing pyroptosis—a highly inflammatory form of programmed cell death mediated by gasdermin D cleavage [27]. This coordinated response serves to eliminate infected cells while alerting neighboring cells to potential danger.

Inflammasome-Microbiota Crosstalk in Reproductive Health

The inflammasome pathway engages in sophisticated reciprocal communication with the reproductive tract microbiota. Inflammasomes function as crucial sensors that enable the host to distinguish between commensal and pathogenic microorganisms, while simultaneously acting as mediators of host-microbiota communication [27]. The environmental state of the reproductive tract lumen continuously influences host responses through generation of specific signals via IL-1β and IL-18 production, which in turn modulates the microbial ecosystem [27].

Different inflammasome sensors perform specialized functions in reproductive tract immunity. NLRP6 regulates gut microbiota composition and contributes to protection against colitis, with similar mechanisms likely operating in the FRT [27]. NLRP3 plays a pivotal role in maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis, with implications for reproductive tract health [27]. NLRP1 activation in response to microbial threats can influence the abundance of butyrate-producing Clostridiales species, which have demonstrated benefits for inflammatory bowel disease through enhancement of intestinal barrier functions such as mucus production and tight junction formation [27].

Table 2: Inflammasome Types and Their Functions in Mucosal Immunity

| Inflammasome Type | Sensor Components | Activators | Key Functions in Mucosa |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLRP3 | NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1 | ATP, crystals, toxins, viral RNA | Homeostasis maintenance, IL-1β/IL-18 processing, pyroptosis [27] |

| NLRC4 | NLRC4, caspase-1 | Bacterial flagellin, type III secretion systems | Defense against bacterial pathogens, epithelial barrier protection [27] |

| NLRP1 | NLRP1, ASC (human), caspase-1 | Anthrax lethal toxin, Toxoplasma gondii | Microbiota regulation, butyrate producer control [27] |

| AIM2 | AIM2, ASC, caspase-1 | Cytosolic DNA | Defense against intracellular bacteria and viruses [27] |

| Non-canonical | Caspase-11 (mouse), caspase-4/5 (human) | Intracellular LPS | NLRP3 activation, pyroptosis in response to Gram-negative bacteria [27] |

Dysregulated inflammasome activation is increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of various reproductive disorders. Aberrant IL-1β and IL-18 signaling contributes to chronic inflammation characteristic of conditions like endometriosis [27]. In the context of bacterial vaginosis, where the optimal Lactobacillus-dominant microbiota is replaced by diverse anaerobic bacteria, inflammasomes may respond inappropriately to dysbiotic communities, establishing a cycle of inflammation and microbial imbalance [26] [24]. Understanding these complex interactions provides opportunities for novel therapeutic interventions targeting inflammasome activity in reproductive tract disorders.

Natural Killer Cell Dynamics in Mucosal Immunity

Phenotypic and Functional Characteristics of Uterine NK Cells

Natural killer cells within the FRT, particularly uterine NK (uNK) cells, represent specialized lymphocyte populations with unique phenotypic and functional properties distinct from their peripheral blood counterparts. uNK cells, also known as decidual NK (dNK) cells during pregnancy, typically express the surface markers CD56brightCD16- and exhibit reduced cytotoxicity compared to peripheral NK cells while demonstrating enhanced capacity for cytokine and chemokine secretion [23]. This phenotypic specialization aligns with their primary functions in supporting placental development, regulating trophoblast invasion, and maintaining immune tolerance at the maternal-fetal interface.

The functional adaptation of uNK cells includes pronounced secretory activity with production of angiogenic factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF), which are crucial for spiral artery remodeling—a critical process in establishing adequate blood flow to the developing fetus [23]. Additionally, uNK cells contribute to the immunoregulatory microenvironment of the decidua through secretion of cytokines including IL-10, TGF-β, and IFN-γ, which collectively modulate adaptive immune responses and support trophoblast survival while defending against viral infections [23].

The development and function of uNK cells are influenced by multiple factors within the FRT microenvironment. Hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle and during pregnancy significantly impact uNK cell numbers and activity, with progesterone particularly implicated in promoting uNK cell differentiation and function [23]. Additionally, emerging evidence suggests that the reproductive tract microbiota and their metabolic products may indirectly shape NK cell responses through effects on other immune populations and epithelial barrier function.

NK Cell Interactions with Microbiota and Other Immune Sentinels

Uterine NK cells do not operate in isolation but engage in sophisticated crosstalk with other immune sentinels and the reproductive tract microbiota. While direct interactions between uNK cells and commensal microorganisms remain less characterized than for TLRs and inflammasomes, indirect mechanisms undoubtedly contribute to functional integration within the mucosal immune network [23]. uNK cells express various TLRs that can respond to microbial signals, potentially modulating their effector functions in different microbial contexts [23].

The communication between uNK cells and inflammasomes represents a crucial interface in FRT immunity. Inflammasome-derived cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 can profoundly influence NK cell activation, with IL-18 particularly serving as a potent inducer of IFN-γ production [27] [23]. Conversely, NK cells can influence inflammasome activation through secretion of cytokines and direct cellular interactions, creating bidirectional regulatory loops that integrate innate immune responses at the mucosal interface.

Dysregulation of uNK cell function is associated with various reproductive pathologies. In recurrent pregnancy loss and pre-eclampsia, alterations in uNK cell numbers, distribution, or function have been consistently reported [23]. Similarly, endometrial infections and chronic inflammatory conditions like endometriosis display disturbed uNK cell profiles, suggesting their involvement in both physiological and pathological processes within the FRT [23]. Understanding these dynamics offers promising avenues for diagnostic and therapeutic innovation in reproductive medicine.

Integrated Immune Sentinel Crosstalk in the Mucosal Niche

Molecular Integration of TLR, Inflammasome, and NK Cell Signaling

The immune sentinels operating at the mucosal interface do not function as isolated systems but engage in sophisticated molecular crosstalk that generates coordinated immune responses. TLR activation provides priming signals for inflammasome assembly through NF-κB-mediated transcription of pro-IL-1β, pro-IL-18, and inflammasome components themselves [27] [25]. Additionally, TLR signaling induces the expression of co-stimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells, enhancing their capacity to activate NK cells through both cytokine-mediated and direct cell-contact mechanisms.

NK cells express functional TLRs that enable them to respond directly to microbial signals, while simultaneously receiving secondary activation signals from inflammasome-derived cytokines like IL-18 [23]. Activated NK cells produce IFN-γ, which can further amplify TLR signaling in macrophages and dendritic cells, creating a positive feedback loop that enhances antimicrobial defense [23]. Conversely, NK cell-derived cytokines can influence the polarization of T helper cell responses, thereby bridging innate and adaptive immunity at the mucosal interface.

The cellular outcome of this integrated signaling is context-dependent, ranging from controlled inflammation that maintains barrier function during commensal colonization to robust effector responses that eliminate pathogens. Disruption of these carefully orchestrated interactions can lead to either inadequate immunity against genuine threats or excessive inflammation causing tissue damage and promoting dysbiosis—both scenarios associated with reproductive pathology.

Experimental Models for Studying Mucosal Immune Sentinel Crosstalk

Investigating the complex interactions between immune sentinels in the FRT requires sophisticated experimental models that recapitulate key aspects of the native tissue microenvironment. Traditional in vitro systems, including two-dimensional monolayer cultures and Transwell inserts, have provided foundational knowledge but fail to fully capture the physiological tissue architecture, dynamic fluid flow, and cellular complexity of the reproductive tract [26].

Recent advances in organ-on-a-chip technology have enabled development of more physiologically relevant models of the FRT. These microfluidic devices incorporate relevant mechanical cues, tissue-tissue interfaces, and dynamic flow conditions that promote differentiation of epithelial cells and production of mucus with biochemical and hormone-responsive properties similar to living cervix [26]. For instance, human Cervix Chips have been successfully populated with optimal healthy (Lactobacillus crispatus-dominated) versus dysbiotic (Gardnerella vaginalis-dominated) microbial communities, recapitulating in vivo differences in innate immune responses, barrier function, and mucus composition [26].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Mucosal Immunology Studies

| Research Tool | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organ-on-a-Chip Models | Human Cervix Chip, Vagina Chip | Host-microbiome interactions, drug testing | Recreates epithelial-stromal interface, mucus production, hormone responses [26] |

| Microbial Flow Cytometry + Sequencing | mFLOW-Seq | Microbiota composition and immune cell association | High-throughput analysis of microbiota-immune interactions [22] |

| Phage Immunoprecipitation Sequencing | PhIP-Seq | Antibody repertoire profiling against microbiota | Identifies microbial epitopes targeted by host antibodies [22] |

| Germ-Free Animal Models | Germ-free mice | Microbiota-immune system development studies | Reveals microbiota-dependent immune maturation mechanisms [28] [29] |

| Metabolomic Profiling | LC-MS, GC-MS | Microbiota-derived metabolite analysis | Identifies immunomodulatory metabolites (SCFAs, AhR ligands) [29] [24] |

Advanced analytical techniques further enhance our ability to decipher immune sentinel crosstalk. Phage Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (PhIP-Seq) enables comprehensive profiling of antibody responses against microbial antigens, while Microbial Flow Cytometry coupled with Next-Generation Sequencing (mFLOW-Seq) permits high-throughput analysis of microbiota composition and its association with immune cell populations [22]. Metabolomic profiling through mass spectrometry-based approaches identifies microbiota-derived molecules that modulate immune sentinel function, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands [29] [24]. These experimental tools collectively provide unprecedented insight into the dynamic interplay between immune sentinels and the mucosal microenvironment.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

TLR4 Signaling Pathway in Mucosal Immunity

The following diagram illustrates the core TLR4 signaling pathway, a fundamental mechanism by which mucosal immune sentinels detect Gram-negative bacteria and initiate immune responses:

TLR4 Signaling Pathway: This pathway demonstrates the dual signaling mechanism of TLR4 upon recognition of bacterial LPS. The MyD88-dependent pathway leads to pro-inflammatory cytokine production, while the TRIF-dependent pathway induces type I interferon responses.

Inflammasome Activation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the molecular events in canonical inflammasome activation, a critical process for IL-1 family cytokine maturation and pyroptotic cell death:

Inflammasome Activation Pathway: This two-step process involves priming (transcriptional) and activation (assembly) signals that culminate in caspase-1 activation, cytokine maturation, and pyroptotic cell death.

Experimental Workflow for Studying Mucosal Immune Sentinel Crosstalk

The following diagram outlines an integrated experimental approach for investigating the crosstalk between immune sentinels in the mucosal microenvironment:

Experimental Immune Sentinel Workflow: This workflow integrates organ-on-a-chip models with multi-omics approaches to decipher complex interactions between mucosal immune sentinels and the microbiome.

The immune sentinels operating at the mucosal interface—TLRs, inflammasomes, and NK cells—represent integrated components of a sophisticated defense network that maintains reproductive tract homeostasis through constant dialogue with the microbiota. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing their crosstalk provides crucial insights into both physiological immune regulation and pathological processes underlying reproductive disorders.

Future research directions should focus on delineating the spatial and temporal dynamics of these interactions throughout the menstrual cycle and during pregnancy. Advanced modeling systems, particularly organ-on-a-chip platforms that recapitulate the complexity of the FRT microenvironment, offer promising approaches for deciphering the nuanced relationships between specific microbial communities, their metabolic outputs, and immune sentinel function. Additionally, translating these mechanistic insights into targeted therapeutic strategies represents a critical frontier in reproductive medicine, with potential applications ranging from microbiome-based interventions for dysbiosis to immunomodulatory approaches for inflammatory conditions and pregnancy disorders.

The integration of multi-omics datasets—including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiomics—will be essential for constructing comprehensive models of immune sentinel function within the FRT ecosystem. Such efforts will ultimately enable the development of personalized approaches to diagnosing, preventing, and treating reproductive tract disorders based on an individual's unique immune-microbiome axis.

The dynamic interplay between the microbiome and the host immune system represents a critical frontier in mucosal immunology, with profound implications for health and disease. This crosstalk is particularly nuanced within the female reproductive tract (FRT), where it underpinnings essential reproductive processes such as embryo implantation, placentation, and the maintenance of pregnancy [30] [31]. The dialogue between host and microbes is mediated through sophisticated mechanisms involving microbial metabolites, host hormonal signals, and complex epithelial signaling pathways. In the genetically susceptible host, dysregulation of these interactions is increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of a multitude of immune-mediated disorders, including those affecting reproductive health [28] [32]. This review provides an in-depth analysis of the core mechanisms governing microbiome-immune crosstalk, with a specific focus on their operational dynamics within the context of reproductive tract immunology.

Core Mechanisms of Microbiome-Immune Interaction

The symbiotic relationship between the host and its microbiota is maintained through several core mechanistic pathways. These interactions ensure immune homeostasis while providing a robust defense against pathogens.

Metabolite-Mediated Signaling

Microbial metabolites serve as crucial molecular intermediates in host-microbiome communication, influencing immune cell differentiation, function, and epigenetic regulation [33] [34].

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber, exert potent anti-inflammatory effects. They function as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, enabling open chromatin configurations and promoting gene expression programs that drive the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [33] [34]. Additionally, SCFAs bind to G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) such as GPR43 on intestinal epithelial and immune cells, modulating inflammatory responses and enhancing barrier integrity [34] [35].

Tryptophan (Trp) metabolites engage the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a ligand-activated transcription factor. AhR activation regulates the balance between T helper 17 (Th17) cells and Tregs, and is crucial for maintaining intraepithelial lymphocytes and preventing intestinal inflammation [34].

Bile acid (BA) metabolites, produced by gut bacteria, interact with the TGR5 membrane receptor and FXR nuclear receptors, influencing macrophage polarization and the production of inflammatory cytokines [34].

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites and Their Immunomodulatory Effects

| Metabolite Class | Example Metabolites | Producing Bacteria | Immune Receptors | Immunological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Butyrate, Propionate, Acetate | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes | GPR43, GPR109A | Treg differentiation, Anti-inflammatory cytokine production, Barrier strengthening |

| Tryptophan Metabolites | Indole-3-aldehyde, IAId | Lactobacillus spp. | Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) | IL-22 production, Mucosal homeostasis, Th17/Treg balance |

| Bile Acid Metabolites | Secondary bile acids (e.g., DCA, LCA) | Bacteroides, Clostridium | FXR, TGR5 | Macrophage polarization, Inflammatory cytokine regulation |

Hormonal Regulation of Microbiome and Immunity

The female reproductive tract is uniquely governed by fluctuating hormone levels, which directly and indirectly shape the local microbiome and immune responses. Estrogen and progesterone receptors are expressed on various immune cells, including those in the FRT, allowing for direct hormonal regulation of immunity [31] [22].

The vaginal microbiome exhibits dynamic equilibrium in response to hormonal shifts during the menstrual cycle [30]. In healthy pregnancies, the vaginal microbiota becomes more stable and dominated by Lactobacillus species, which is associated with favorable pregnancy outcomes [30] [31]. This stability is attributed to high estrogen levels promoting glycogen deposition in the vaginal epithelium, which Lactobacillus species metabolize into lactic acid, maintaining a protective acidic environment [31]. Conversely, conditions like bacterial vaginosis (BV), characterized by a loss of Lactobacillus dominance, have been linked to an increased risk of adverse outcomes such as preterm birth, potentially through hormone-driven immune dysregulation [30] [22].

Epithelial Barrier and PRR Signaling Networks

The single layer of intestinal epithelium and the mucosal surfaces of the FRT serve as the primary physical interface with the microbiota. A dense mucus layer, primarily composed of mucin glycoproteins like MUC2, separates commensals from the epithelial surface [28]. This barrier is dynamic; microbial signals, such as the metabolite indole, can promote the fortification of the epithelial barrier through the upregulation of tight junction proteins [28] [35].

Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs), are expressed on epithelial and immune cells and are essential for monitoring the microbial environment [28] [34]. They recognize conserved microbial structures known as Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs). The interplay between the microbiota and PRRs is crucial for maintaining homeostasis. For instance, polysaccharide A (PSA) from the commensal Bacteroides fragilis is recognized by TLR2, leading to the activation of anti-inflammatory gene programs that promote immune tolerance [28]. Similarly, in the FRT, epithelial defenses, including antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and secretory IgA (sIgA), are regulated by these interactions and are critical for preventing pathogen invasion while tolerating commensals [22].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Elucidating causal relationships in microbiome-immune research requires sophisticated experimental models and protocols.

Gnotobiotic Mouse Models

Germ-free (GF) mice, raised in sterile isolators devoid of any microorganisms, are foundational tools. These animals exhibit profound immune defects, including underdeveloped gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), reduced secretory IgA, fewer intraepithelial lymphocytes, and imbalances in T helper cell subsets [33]. The colonization of GF mice with defined microbial communities (gnotobiotic mice) or human microbiota (humanized mice) allows researchers to dissect the specific role of microbes in immune system development and function [33]. For example, monocolonization of GF mice with segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) is sufficient to induce the differentiation of Th17 cells in the lamina propria [28].

Protocol: Humanized Microbiota Mouse Model

- Donor Sample Preparation: Human fecal or reproductive tract microbiota samples are collected under controlled conditions and processed anaerobically to preserve microbial viability.

- Receiver Mouse Preparation: Adult GF mice are used as recipients.

- Microbiota Transplantation: Mice are orally gavaged with the prepared microbial suspension.

- Equilibration Period: Mice are housed under specific pathogen-free conditions for 4-6 weeks to allow for stable microbial engraftment.

- Analysis: Immune phenotypes and microbial composition are analyzed in tissues and contents of the gastrointestinal or reproductive tract.

Multi-Omics Integration

Technological advances now allow for the comprehensive profiling of host-microbiome interactions.

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: Used for taxonomic profiling of bacterial communities [30] [33].

- Shotgun Metagenomics: Sequences all microbial DNA in a sample, allowing for strain-level identification and functional gene analysis [33].

- Metatranscriptomics: Profiles gene expression of the microbial community, revealing real-time metabolic activity [33].

- Metabolomics: Identifies and quantifies small molecule metabolites produced by the microbiome and host using mass spectrometry [33].

Computational tools like QIIME, METAXA2, and HUMAnN2 are used to analyze and integrate these complex datasets [33].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways involved in metabolite-mediated microbiome-immune crosstalk.

Metabolite-Mediated Immune Crosstalk

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Microbiome-Immune Research

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Models | Germ-free (GF) mice; Gnotobiotic mice | Establish causality by studying immune development in absence or defined presence of microbes. |

| Humanized Mouse Models | Bone marrow-liver-thymus (BLT) humanized mice | Study human-specific immune responses to microbiota in an in vivo setting. |

| Sequencing Technologies | 16S rRNA (Illumina MiSeq); Shotgun Metagenomics (Illumina NovaSeq) | Profile microbial community composition and functional potential. |

| Metabolomics Platforms | LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Identify and quantify microbial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, tryptophan metabolites). |

| Immunological Assays | Flow Cytometry Panels (e.g., for Treg, Th17); Multiplex Cytokine Assays (Luminex) | Characterize immune cell populations and cytokine profiles in response to microbial cues. |

| PRR Agonists/Antagonists | Ultra-pure LPS (TLR4 agonist); Pam3CSK4 (TLR1/2 agonist) | Mechanistically probe specific host signaling pathways involved in microbe sensing. |

| Tos-aminoxy-Boc-PEG4-Tos | Tos-aminoxy-Boc-PEG4-Tos Linker | |

| VU0361747 | VU0361747, CAS:1309976-66-6, MF:C19H17FN2O2, MW:324.36 | Chemical Reagent |

The mechanisms of microbiome-immune crosstalk, mediated by metabolites, hormones, and epithelial signaling, form a complex, interconnected network that is vital for maintaining health. Within the specialized context of the female reproductive tract, these interactions are fine-tuned by hormonal cycles and are critical for successful reproductive outcomes. Dysbiosis disrupts this delicate balance, leading to a breakdown in immune tolerance and barrier function, thereby contributing to disease pathogenesis. The continued refinement of experimental models, multi-omics technologies, and analytical tools, as outlined in this review, is essential for deciphering these complex interactions. This deeper understanding will undoubtedly pave the way for novel microbiome-targeted diagnostics and therapeutics for immune and reproductive disorders.

Bridging Discovery and Therapy: Tools, Models, and Microbiome-Targeted Interventions

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three advanced methodologies revolutionizing microbiome research in reproductive tract immunology. Multi-omics integration, single-cell analysis, and gnotobiotic models collectively enable researchers to decipher the complex interactions between reproductive tract microbiota and host immunity with unprecedented resolution. By synthesizing current protocols and applications, this whitepaper serves as a comprehensive resource for scientists and drug development professionals investigating microbiome-mediated mechanisms in reproductive health and disease. The integration of these approaches provides a powerful framework for identifying novel therapeutic targets and diagnostic biomarkers for conditions ranging from bacterial vaginosis to preterm birth.

Multi-Omics Integration in Reproductive Tract Research

Conceptual Framework and Technical Approaches

Multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift in microbiome research, moving beyond simple taxonomic characterization to reveal functional host-microbe interactions. This approach systematically combines data from genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic analyses to construct comprehensive models of biological systems [36] [37]. In reproductive tract immunology, multi-omics reveals how microbial communities influence host immunity through their metabolic outputs and transcriptional activity.

The fundamental principle of multi-omics integration involves the simultaneous measurement and computational integration of multiple molecular data types from the same biological sample. This enables researchers to connect microbial composition and genetic potential with actual functional outputs and host responses [37]. For example, while metagenomics can identify microbial taxa and genes, metatranscriptomics reveals which genes are actively expressed, metabolomics identifies the resulting metabolites, and proteomics characterizes the functional proteins that execute cellular processes [37].

Table 1: Multi-Omics Technologies in Reproductive Tract Research

| Omics Layer | Technology Options | Key Outputs | Applications in Reproductive Immunology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | 16S rRNA sequencing, Shotgun metagenomics | Microbial composition, phylogenetic relationships, genetic potential | Identifying dysbiosis patterns, virulence factors, antimicrobial resistance genes [38] |

| Metatranscriptomics | RNA-Seq | Gene expression profiles, active metabolic pathways | Understanding microbial response to host environment, expressed virulence factors [37] |

| Metabolomics | LC-MS, UHPLC-MS | Small molecule metabolites, signaling molecules | Identifying immunomodulatory metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, amines) [39] |

| Proteomics | Multiplex immunoassays, MS-based proteomics | Protein expression, post-translational modifications | Quantifying immune factors, inflammatory mediators [38] |

| Integrative Analysis | Computational integration tools | Multi-layer interaction networks | Revealing host-microbe signaling pathways, biomarker discovery [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Protocol 1: Integrated Microbiome-Metabolome Analysis from Cervicovaginal Samples