Overcoming Low Microbial Diversity: A Troubleshooting Guide for Robust Sample Processing in Research and Drug Development

Accurate characterization of microbial communities is paramount for meaningful research and drug development outcomes.

Overcoming Low Microbial Diversity: A Troubleshooting Guide for Robust Sample Processing in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

Accurate characterization of microbial communities is paramount for meaningful research and drug development outcomes. However, samples with low microbial biomass are exceptionally vulnerable to contamination, technical artifacts, and biases during processing, which can severely distort diversity measurements and lead to spurious conclusions. This article provides a comprehensive, evidence-based framework for troubleshooting low diversity signals. It covers foundational concepts of low-biomass environments, methodological best practices for sample collection and processing, advanced troubleshooting and optimization protocols for DNA extraction and cultivation, and robust validation strategies through controls and multi-method integration. By synthesizing current guidelines and comparative studies, this guide empowers scientists to distinguish true biological signals from technical noise, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of their microbiome data.

Understanding the Low Biomass Challenge: Why Your Sample Processing Matters

Defining Low Microbial Biomass Environments and Their Unique Vulnerabilities

Low microbial biomass environments contain minimal levels of microorganisms, often approaching the detection limits of standard DNA-based sequencing methods. These environments pose unique challenges for researchers because even small amounts of contamination can severely distort results and lead to incorrect conclusions. This technical support guide addresses the specific vulnerabilities of these environments and provides evidence-based troubleshooting solutions to ensure data integrity in your research.

What Constitutes a Low Microbial Biomass Environment?

Low microbial biomass environments are characterized by extremely limited microbial presence, where the target DNA "signal" can be easily overwhelmed by contaminant "noise" [1]. These environments require special consideration at every stage of research, from sample collection and handling through data analysis and reporting.

Common Low Microbial Biomass Environments

- Human Tissues and Fluids: Fetal tissues, respiratory tract, breastmilk, blood, and certain pathological samples [1] [2].

- Built Environments: Cleanrooms, hospital operating rooms, and metal surfaces where strict contamination control is necessary [1] [3].

- Natural Environments with Extreme Conditions: The atmosphere, hyper-arid soils, deep subsurface, ice cores, treated drinking water, and hypersaline brines [1].

- Specific Research Materials: Plant seeds, ancient and poorly preserved samples, and certain animal guts [1].

Table 1: Major Contamination Sources in Low Microbial Biomass Research

| Contamination Source | Description | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Human Operators | Cells, skin flakes, hair, or aerosol droplets from researchers [1] [2] | False detection of human-associated microbes (e.g., Cutibacterium acnes) [3] |

| Sampling Equipment | Reusable tools, collection vessels, and gloves that are not properly decontaminated [1] | Introduction of environmental or cross-sample contaminants |

| Laboratory Reagents & Kits | Microbial DNA present in extraction kits and PCR reagents ("kitome") [1] [3] | Background contamination that dominates the true signal in ultra-low biomass samples |

| Laboratory Environment | Airborne particles and surfaces in the lab [1] | Introduction of common laboratory and environmental contaminants |

| Cross-Contamination | Transfer of DNA between samples during processing, e.g., through well-to-well leakage [1] | False positives and distorted ecological patterns |

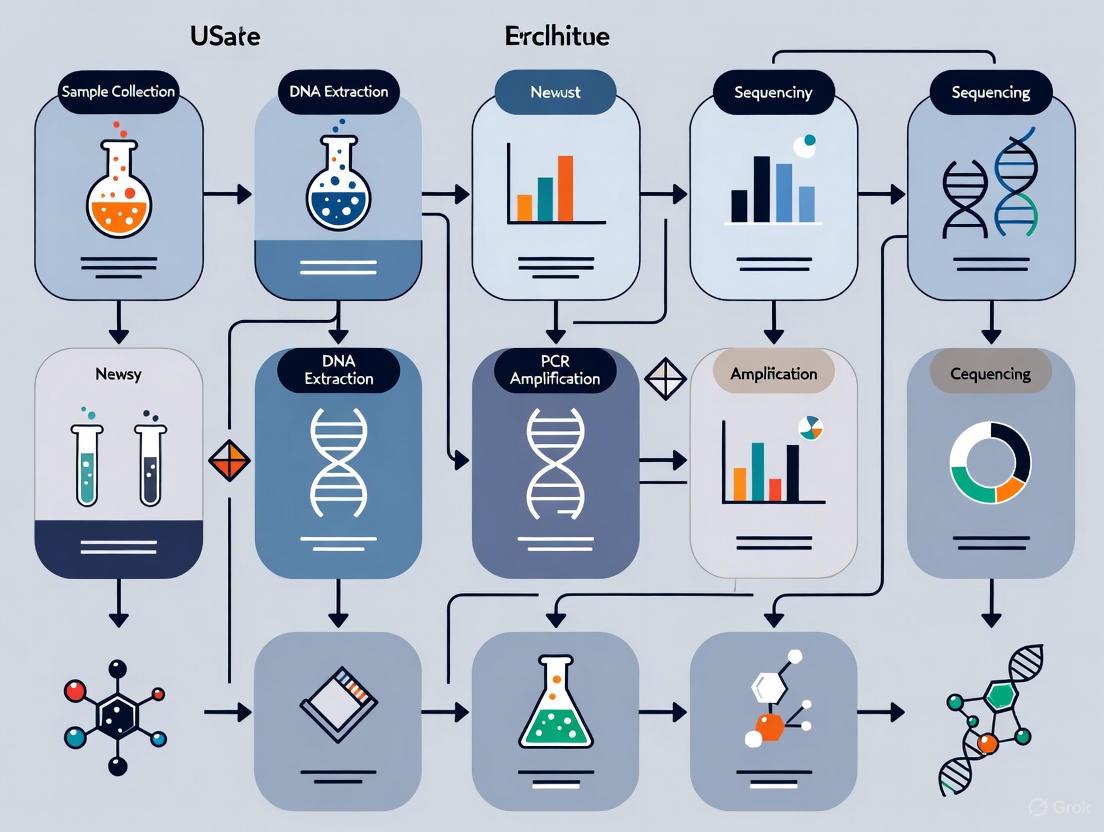

Experimental Design and Workflow

A contamination-conscious experimental design is the most critical step for successful low-biomass research. The diagram below outlines a workflow that integrates contamination control at every stage.

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How can I distinguish true microbial signals from contamination in my data?

Challenge: In low-biomass samples, contaminant DNA from reagents, kits, and the environment can be more abundant than the target DNA, making it difficult to identify the true signal [1] [3].

Solutions:

- Implement Extensive Controls: Include multiple negative controls at every stage (sample collection, DNA extraction, library preparation). Sequence these controls alongside your samples [1] [3].

- Bioinformatic Subtraction: Use specialized tools to identify and subtract contaminants by comparing your samples to the profiles obtained from your negative controls. Be aware that these tools can struggle if contamination is extensive and variable [1].

- Replicate and Validate: Consistent detection of a microbial taxon across true sample replicates, especially at higher abundances than in control samples, increases confidence.

FAQ 2: My negative controls show high microbial DNA. What went wrong?

Challenge: Detection of significant microbial DNA in negative controls indicates pervasive contamination.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Audit Reagents: Check that all reagents, especially DNA extraction and PCR kits, are certified DNA-free or have been tested for low background contamination [1] [3].

- Review Lab Practices: Ensure that work is performed in a dedicated, clean workspace (e.g., PCR hood, if possible). Use sterile, single-use plasticware and decontaminate surfaces and equipment with solutions that destroy free DNA (e.g., 10% bleach, followed by 70% ethanol) [1].

- Verify Personnel Technique: Confirm that researchers are wearing appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, lab coats, masks, and potentially cleansuits to minimize human-derived contamination [1].

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for collecting low-biomass samples to minimize contamination?

Challenge: Contamination introduced during sampling is irreversible and can invalidate a study.

Protocol for Contamination-Conscious Sampling:

- Decontaminate Equipment: Use single-use, DNA-free collection tools (swabs, vessels). If reusables are necessary, decontaminate with 80% ethanol (to kill cells) followed by a DNA-degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or UV-C irradiation [1].

- Use Barriers and PPE: Cover exposed skin with gloves, masks, goggles, and cleansuits to prevent contamination from researchers [1] [2].

- Collect Process Controls: During sampling, also collect controls such as an empty collection vessel, a swab of the air, or an aliquot of the preservation solution. These are essential for identifying contamination sources introduced during collection [1].

FAQ 4: How does sample biomass level affect my choice of sequencing and analysis methods?

Challenge: Standard protocols designed for high-biomass samples (e.g., human gut, soil) are often unsuitable for low-biomass applications.

Methodological Adjustments:

- Sequencing Protocol Selection: For ultra-low biomass samples, specialized library prep kits designed for low DNA input may be required. In some cases, adding nonspecific carrier DNA or increasing PCR cycles can help, but this must be done cautiously as it can also amplify contaminants [3].

- Analysis Considerations: Phylogenetic-based analysis methods can be more robust than Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU)-based approaches when sequence coverage is low [4]. Normalize the number of sequences across all samples before comparing diversity indices, as these values are sensitive to sample size [4].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Low-Biomass Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples / Properties | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Free Reagents | Certified DNA-free water, extraction kits, and PCR mixes [1] [3] | Minimizes background contamination from the "kitome," which is critical for ultra-low biomass samples. |

| Surface Decontaminants | 80% Ethanol, Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), UV-C light, Hydrogen peroxide [1] | Ethanol kills cells; bleach/UV-C destroys residual DNA. A two-step process is recommended for thorough decontamination. |

| Specialized Library Prep Kits | Kits validated for low DNA input (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit, Oxford Nanopore Rapid PCR Barcoding with modifications) [5] [3] | Enables library construction from minimal DNA (as low as 500 pg), improving the chances of detecting the true signal. |

| Sample Collection Devices | Single-use, pre-sterilized swabs; novel devices like the SALSA (Squeegee-Aspirator for Large Sampling Area) [3] | Maximizes recovery efficiency and minimizes sample loss or contamination during the collection process. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Gloves, masks, goggles, cleansuits, shoe covers [1] | Creates a barrier between the researcher and the sample, reducing contamination from human skin, hair, and aerosols. |

Successfully researching low microbial biomass environments demands rigorous contamination control throughout the entire experimental process. By implementing the guidelines, troubleshooting strategies, and reagent solutions outlined in this document, you can significantly reduce contamination, properly identify its sources, and generate more reliable and interpretable data for your research.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common contamination sources in low-biomass research? The most prevalent contamination sources are reagents and kits (including extraction kits and water), laboratory equipment and surfaces (both external and internal to equipment like liquid handlers), and cross-contamination between samples during processing [6] [1] [7]. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, shared equipment is a primary cause of cross-contamination [8] [9].

My negative controls show microbial growth. What should I do? First, check your water supply and reagents [6]. Test your purified water and reagents by using them in a control culture media to see if microbial growth occurs. Secondly, review your sterile technique, including the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and ensure all equipment has been properly sterilized. Finally, increase your process controls by including more negative controls (e.g., empty collection vessels, swabs of the air, extraction blanks) to help pinpoint the exact source of contamination [1] [7].

How can I distinguish true microbial signal from contamination in my data? Robust experimental design is key. Always include multiple types of negative controls (e.g., sample collection controls, extraction blanks, no-template PCR controls) that undergo the exact same process as your samples. During data analysis, use computational decontamination tools that leverage these controls to identify and subtract contaminant sequences. Be cautious, as these methods can struggle if controls are not representative or if well-to-well leakage has occurred [1] [7].

Our lab uses shared equipment. How can we prevent cross-contamination? Implement and validate a rigorous cleaning protocol between uses. For equipment that comes into direct contact with samples, use a two-step process: decontaminate with 80% ethanol to kill organisms, followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., bleach, UV-C light) to remove residual DNA [1]. For larger or fixed equipment, establish and adhere to a documented cleaning schedule and use single-use materials where possible [6] [10].

What are the best practices for storing samples to prevent contamination? Immediate freezing at -80°C is the gold standard for preserving microbiome integrity. If this is not feasible, refrigeration at 4°C can be effective for some sample types, and the use of preservative buffers (e.g., AssayAssure, OMNIgene·GUT) can help maintain microbial stability at room temperature for a limited period [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Use this flowchart to systematically identify potential contamination sources in your lab workflow.

Diagram 1: A workflow to diagnose common contamination sources.

Guide 2: Addressing Reagent and Kit Contamination

Problem: Contaminating microbial DNA is introduced from reagents, kits, or water, which is especially impactful in low-biomass studies [1] [7].

Solutions:

- Test Reagents: Use an electroconductive meter to check water purity or culture media with only the water/reagent as a sample [6].

- Use Certified Reagents: Source DNA-free, certified reagents and water when possible.

- Include Controls: Always include negative extraction controls (blanks) that use water instead of sample to identify reagent-derived contaminants [7].

- UV Irradiation: Pre-treat reagents with UV light to degrade contaminating DNA, if compatible with the reagent [1].

Guide 3: Preventing Equipment and Surface Contamination

Problem: Contaminants are introduced from laboratory surfaces, tools, or equipment interiors [6] [10].

Solutions:

- Establish a Cleaning Schedule: Create and document a strict schedule for cleaning and sterilizing all equipment. Use autoclaving and UV-C sterilization where applicable [6].

- DNA Decontamination: For surfaces and equipment, use a two-step process: clean with 80% ethanol, followed by a DNA-degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) to remove residual nucleic acids [1].

- Automate: Use automated liquid handlers with enclosed, HEPA-filtered hoods to create a contamination-free workspace and reduce human contact with samples [6].

- Use Laminar Flow: Perform sample transfers in a laminar flow hood to keep airborne particles from settling on samples [6].

Guide 4: Minimizing Sample Cross-Contamination

Problem: DNA from one sample leaks or is transferred to another sample, a phenomenon known as "well-to-well leakage" or the "splashome" [7].

Solutions:

- Optimize Lab Workflow: Design a unidirectional workflow from "clean" to "dirty" areas to prevent processed samples from contaminating new ones. Keep samples organized and in their proper locations [6].

- Physical Barriers: Use physical seals or caps on sample plates during centrifugation and vortexing. When possible, include blank wells between samples on PCR plates to act as buffers [7].

- Reduce Touches: Map out your experimental procedure and find ways to reduce the number of sample transfers and physical touches, as each touch is a potential contamination point [6].

- Decontaminate Gloves: Change gloves frequently and decontaminate them with ethanol between handling different samples [1].

Contamination Data and Reagent Solutions

This table summarizes real-world contamination trends identified from pharmaceutical recall databases, illustrating the prevalence and impact of various contaminants [8].

| Contaminant/Impurity Type | Examples | Common Causes & Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Contaminants | Bacteria (e.g., Burkholderia cepacia), viruses, fungi | Contaminated water systems, raw materials (animal sera, human plasma), improper aseptic techniques in compounding pharmacies [8]. |

| Process-Related Impurities | Genotoxic impurities (e.g., nitrosamines), reaction byproducts | Unexpected reactions from changing reactants, failure to characterize impurities during process changes, poor cleaning leading to residue buildup [8]. |

| Metal Contaminants | Stainless steel (e.g., 316L), chromium, aluminum | Wear and tear or friction from manufacturing equipment; human error in equipment assembly [8]. |

| Packaging-Related Contaminants | Glass flakes, rubber particles, plasticizers (e.g., phthalates) | Incompatibility between packaging and product, degradation from poor storage conditions (prolonged time, high temperature) [8]. |

| Drug Cross-Contamination | Potent drugs (e.g., antihypertensives, cytotoxics) | Use of shared manufacturing equipment with inadequate cleaning validation, human error leading to product mix-ups [8] [9]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

This toolkit lists key materials and reagents used to prevent, identify, and control contamination in microbiome research.

| Item | Function & Role in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| HEPA-Filtered Laminar Flow Hood | Provides a sterile workspace with unidirectional, particulate-free air to protect samples from airborne contaminants during open-bench procedures [6]. |

| DNA-Free Water | Used as a solvent for reagents and PCR mixes to prevent the introduction of microbial DNA that can skew results, especially in low-biomass studies [6] [1]. |

| UV-C Light Source | Used to sterilize surfaces, equipment, and some reagents by degrading contaminating DNA, helping to eliminate nucleic acids that survive standard cleaning [1]. |

| Sterile Swab Kits | Allow for aseptic collection of surface and tissue samples. Using single-use, pre-sterilized kits prevents introducing contaminants during the sampling process itself [12]. |

| DNA Degrading Solution (e.g., Bleach) | Used to wipe down surfaces and equipment to destroy residual contaminating DNA that is not removed by ethanol cleaning alone [1]. |

| Preservative Buffers (e.g., AssayAssure) | Maintain microbial stability and composition in samples that cannot be immediately frozen, preventing overgrowth of contaminants or degradation of the native microbiome [11]. |

| Validated DNA Extraction Kits | Kits designed for low-biomass samples often include protocols to minimize reagent contamination. Consistent use allows for better identification of background "kitome" contaminants [11] [13]. |

| Single-Use, Filter Pipette Tips | Prevent aerosol carryover and cross-contamination between samples during liquid handling, a common source of well-to-well leakage [7] [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Control

Protocol 1: Establishing a Comprehensive Contamination Control Plan

A proactive plan is essential for reliable results [10].

- Risk Assessment: Identify all potential contamination sources for your specific samples and processes (personnel, environment, reagents, equipment).

- Develop SOPs: Create detailed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for:

- Cleaning & Sterilization: Define methods, frequencies, and responsible personnel for all equipment and surfaces [6].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Mandate lab coats, gloves, hairnets, and masks. Specify changing gloves between samples [6] [1].

- Waste Disposal: Ensure safe disposal of contaminated materials.

- Implement Physical Controls:

- Training & Documentation: Train all personnel rigorously on contamination control SOPs. Maintain detailed records of cleaning, maintenance, and any contamination incidents [10].

Protocol 2: Collecting Process Controls for Low-Biomass Studies

In low-biomass research, contamination is inevitable; the goal is to identify it. Process controls are non-sample specimens that undergo the exact same processing as your real samples to capture the "background noise" of contamination [1] [7].

- Sample Collection Controls:

- Empty Collection Vessel: Place an empty, sterile collection tube in the sampling environment.

- Field Swabs: Swab the air in the sampling environment or swab the PPE of the sampling personnel.

- Preservation Solution Aliquot: Take an aliquot of the solution used to preserve samples.

- DNA Extraction Controls:

- Amplification & Sequencing Controls:

- No-Template Control (NTC): In PCR, use a reaction mix containing all reagents except the DNA template. This identifies contamination in your PCR master mix or primers [7].

- Implementation:

- Include these controls in every batch of samples processed.

- We recommend including at least two controls per type to account for variability and ensure reliability [7].

The Critical Impact of Contamination on Diversity Metrics and Data Interpretation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are low-biomass samples particularly vulnerable to contamination, and how does this affect diversity metrics? In low-microbial biomass samples, the genetic material from contaminants can outnumber the DNA from the actual sample. This leads to severe biases where contamination constitutes the majority (e.g., >75%) of generated sequence data. This inflates perceived microbial diversity (alpha diversity) and distorts the true biological differences between sample groups (beta diversity), potentially leading to spurious conclusions about the presence of a native microbiome [1] [14].

FAQ 2: What are the primary sources of contamination in microbiome studies? Contamination can be introduced at virtually every stage of the workflow:

- Sample Collection: Human operators, sampling equipment, and the local environment [1] [14].

- Reagents and Kits: DNA extraction kits and library preparation reagents contain microbial DNA, often called the "kitome" [12] [14].

- Cross-contamination: During laboratory processing, DNA can transfer between samples, for instance, through well-to-well leakage during PCR setup [1].

FAQ 3: What types of negative controls are essential for identifying contamination? A robust experimental design includes multiple types of controls to trace contamination sources:

- Sampling Controls: Swabs of the air, gloves, or sampling equipment to account for environmental exposure during collection [1].

- Extraction Blanks: Reagents taken through the DNA extraction process without any sample to identify the "kitome" [12] [14].

- Library Preparation Blanks: Water or buffer used in the PCR and library preparation steps to detect contaminants from these reagents [14].

FAQ 4: How can I differentiate between a true low-diversity signal and a signal caused by contamination?

Rigorous use of negative controls is mandatory. By sequencing these controls alongside your samples, you can use statistical algorithms (e.g., decontam in R) to identify and remove sequences also found in the controls. Furthermore, correlating DNA-based findings with other methods, such as bacterial culture, can confirm the presence of viable endogenous microbes [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inflated or Skewed Alpha Diversity in Low-Biomass Samples

Potential Cause: Contaminating DNA from reagents or the sampling environment is being sequenced, creating a false signal of high diversity.

Solution:

- Implement Stringent Laboratory Practices:

- Use DNA-free reagents and single-use, sterilized plasticware where possible [1].

- Decontaminate workspaces and equipment with solutions that degrade nucleic acids (e.g., 10% bleach, followed by 70% ethanol to remove bleach residue) [1].

- Use separate, dedicated rooms or cabinets for pre- and post-PCR work to prevent amplicon contamination.

- Integrate Comprehensive Controls: Include extraction blanks and library preparation blanks in every batch of samples processed [14].

- Apply Bioinformatics Decontamination: Use the data from your negative controls in a contamination-identification algorithm. The table below summarizes the impact of contamination and the effect of decontamination as demonstrated in a bovine milk study [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Contamination and Decontamination in a Bovine Milk Microbiome Study

| Metric | Before Decontamination | After Decontamination |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of sequences identified as contaminant | >75% | Not Applicable |

| Predominant genera in milk samples | Mixed community of contaminants and endogenous bacteria | Staphylococcus and Acinetobacter |

| Bacterial culture results | Not performed | Growth of Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium in 50% of samples |

| Conclusion on milk microbiome | Artificially inflated diversity, unreliable composition | More dispersed, less diverse, compositionally distinct true community |

Problem: Unreliable Beta Diversity and Sample Groupings (PCoA/PERMANOVA)

Potential Cause: Variable levels of contamination across samples or cross-contamination is distorting the true ecological distances between samples.

Solution:

- Standardize Sample Handling: Ensure all samples are collected, stored, and processed in an identical manner to minimize technical variation [1].

- Prevent Cross-Contamination:

- Use fresh gloves between handling different samples.

- Use aerosol-resistant pipette tips.

- Include a dye tracer in drilling or cutting fluids to monitor for leakage between samples [1].

- Leverage Experimental Design: For sample types where the true microbiome is expected to be minimal or non-existent (e.g., sterile buffers, negative controls), include them in your beta diversity analysis. Their position in the ordination plot will reveal the "cloud of contamination," allowing you to interpret which experimental samples are indistinguishable from it [1] [12].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Item | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| DNA Degrading Solution (e.g., Bleach) | Destroys contaminating free DNA on surfaces and equipment that can persist after standard sterilization [1]. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) | Commonly used for soil and environmental samples; its bead-beating step is effective for lysing tough microbial cells. The associated "kitome" must be characterized with extraction blanks [12]. |

| Sterile FloqSwabs | Single-use swabs for consistent surface sampling, preventing cross-contamination between sampling locations [12]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | A dye that penetrates cells with compromised membranes (dead cells) and covalently binds to their DNA upon light exposure, preventing its amplification. This helps differentiate DNA from intact/viable cells versus free DNA or dead cells [14]. |

| Synthetic DNA (Spike-in) | An artificial, known DNA sequence added to samples in a controlled amount. It serves as an internal standard for quantifying absolute microbial abundance and identifying PCR inhibition [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Sampling and Control Workflow for Low-Biomass Surfaces

This protocol outlines a method for sampling low-biomass surfaces (e.g., equipment handles, cleanroom surfaces) to monitor microbial contamination while accounting for potential contaminants.

Methodology:

- Preparation:

- Decontaminate sampling surfaces and gloved hands with 80% ethanol followed by a DNA-degrading solution (e.g., 0.5% sodium hypochlorite) if compatible with the surface material [1].

- Prepare and label sterile swab kits and sample containers.

- Sample Collection:

- Moisten a sterile swab (e.g., FloqSwab) in sterile Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Swab the target surface area (e.g., 10 cm x 10 cm) thoroughly, using horizontal, vertical, and diagonal strokes while rotating the swab [12].

- Return the swab to its container and seal.

- Control Collection:

- Storage and Processing:

- Refrigerate samples at 4°C immediately after collection for short-term storage.

- Transfer to -80°C for long-term storage until DNA extraction.

- Process all samples and controls through DNA extraction and sequencing simultaneously using the same kit and reagent batches [12].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the full experimental and bioinformatics pipeline for a robust low-biomass study.

Technical FAQs: Resolving the Placental Microbiome Controversy

FAQ 1: What is the core methodological problem underlying the placental microbiome debate? The central issue is the challenge of low microbial biomass. In environments like the placenta, where microorganisms are presumed to be absent or extremely rare, the minimal microbial DNA signal detected by sensitive sequencing techniques can be easily overwhelmed or mistaken for background DNA contamination originating from laboratory reagents, sampling equipment, or the laboratory environment itself [15] [1] [16]. Distinguishing a true signal from this contaminant "noise" is the primary methodological hurdle.

FAQ 2: What are the key pieces of evidence cited by both sides of the debate? The scientific community remains divided, with interpretations of the same data leading to opposing conclusions, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Evidence in the Placental Microbiome Debate

| Evidence for a Placental Microbiome | Evidence for a Sterile Placenta |

|---|---|

| Detection of bacterial DNA in placental tissue via high-throughput sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA gene sequencing) [17] [18]. | Re-analysis of sequencing data showing placental bacterial profiles cluster by study and mode of delivery, not biological signal [15]. |

| Identification of specific bacterial phyla (e.g., Firmicutes, Proteobacteria) with compositions differing from other body sites [17] [18]. | Bacterial signals in term cesarean-delivered placentas become indistinguishable from technical controls after stringent decontamination analysis [15]. |

| Studies reporting bacterial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs) in meconium and inflammatory cytokines linked to bacterial profiles in amniotic fluid [19]. | Existence of germ-free mammals, which are derived via Cesarean-section and raised in sterile conditions, contradicting in utero colonization [20] [16]. |

| Potential microbial origins from maternal oral, gut, and vaginal microbiota through hematogenous spread or ascending migration [17] [21]. | Widespread contamination from DNA extraction kits and reagents ("kit-ome") can explain most, if not all, detected bacterial DNA [22] [16]. |

FAQ 3: What is the "kit-ome" and how does it mislead research? The "kit-ome" refers to the collective microbial DNA contamination present in laboratory reagents, including DNA extraction kits and PCR master mixes [22]. This contaminating DNA is co-purified and sequenced alongside the target DNA from the sample. In high-biomass samples like stool, the authentic signal dwarfs the contamination. However, in low-biomass samples like the placenta, the "kit-ome" can constitute most or even all of the apparent microbial community, leading to reports of environmentally-derived bacteria (e.g., Bradyrhizobium, which lives on plant roots) in human tissues [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Pitfalls in Low-Biomass Microbiome Research

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for identifying and addressing contamination throughout a low-biomass microbiome study.

Troubleshooting Steps

Step 1: Pre-Sampling & Experimental Design

- Problem: Inadequate control planning leads to inability to distinguish signal from noise.

- Solution: Plan your statistical analysis and control strategy at the start [23]. This includes determining the number and type of negative controls (e.g., extraction blanks, PCR blanks, sampling blanks) needed to robustly identify contaminants. A power analysis is recommended for hypothesis-testing studies [23].

Step 2: Sample Collection & Handling

- Problem: Contamination is introduced during the sampling procedure itself.

- Solution: Implement a contamination-informed sampling design [1]. Use single-use, DNA-free collection vessels. Decontaminate reusable equipment with ethanol followed by a DNA-degrading solution (e.g., bleach). Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) like gloves, masks, and cleansuits to limit human-derived contamination [1]. Crucially, collect procedural controls, such as an empty collection vessel or a swab exposed to the air in the sampling environment [1].

Step 3: Laboratory Processing

- Problem: Reagent and cross-sample contamination during DNA extraction and library preparation.

- Solution: Include multiple negative controls from DNA extraction and subsequent steps in every batch of samples processed [23] [1]. Where feasible, use multiple DNA extraction kits to check for kit-specific contaminants [22]. The use of synthetic DNA spike-in controls can help quantify the limit of detection and account for amplification biases [20].

Step 4: Data Analysis & Interpretation

- Problem: Failure to bioinformatically identify and remove contaminant sequences.

- Solution: Aggressively profile and subtract contaminants using dedicated tools (e.g., the

decontamR package) that identify sequences prevalent in negative controls [15] [16]. Always compare the microbial profile of your samples directly to your negative controls. Be skeptical of results that show a high degree of overlap with common environmental bacteria or known reagent contaminants [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and solutions for conducting robust low-biomass microbiome research.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Biomass Studies

| Item | Function & Importance | Considerations & Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Removal Solutions (e.g., bleach, UV-C light) [1] | Decontaminates sampling equipment and work surfaces by degrading trace DNA that remains even after sterility. | Critical for reducing background "signal." Autoclaving and ethanol alone do not remove persistent DNA. |

| Process Validation Controls (Extraction & PCR Blanks) [15] [23] | Reveals the "kit-ome" and environmental contaminants introduced during wet-lab workflows. The cornerstone of credible data. | Must be processed in the exact same batch and alongside experimental samples. Ignoring them invalidates results. |

| Sampling Controls (Blank swabs, air samples) [1] | Identifies contamination introduced specifically during the sample collection procedure. | Examples include swabbing the glove of the collector or exposing a swab to the operating theatre air [1]. |

| Spike-in Controls (e.g., Salmonella bongori, synthetic sequences) [22] [19] | Acts as an internal standard to verify that the entire workflow can detect low levels of microbes and to monitor PCR inhibition. | Should be added in low, known quantities to avoid overwhelming any potential authentic signal. |

| Contamination Identification Software (e.g., Decontam) [15] | Bioinformatic tool that uses prevalence or frequency in negative controls to identify and remove contaminant sequences from data. | Essential final step. However, its efficacy depends on the quality and number of negative controls provided. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) (gloves, masks, cleansuits) [1] | Creates a barrier between the operator (a major source of contamination) and the sample. | Reduces contamination from human aerosol droplets, skin, and hair [1]. More extensive PPE is needed for ultra-clean protocols. |

| Fmoc-D-Dap(Boc)-OH | Fmoc-D-Dap(Boc)-OH, CAS:198544-42-2, MF:C23H26N2O6, MW:426.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-His(Trt)-OH | Fmoc-His(Trt)-OH, CAS:109425-51-6, MF:C40H33N3O4, MW:619.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Building a Robust Workflow: Best Practices from Sample to Sequence

Decontamination Protocols for Sampling Equipment and Surfaces

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is decontamination especially critical for low microbial biomass studies? Samples with low microbial biomass (e.g., certain human tissues, blood, or clean water) contain minimal target DNA. Contaminants introduced from sampling equipment or surfaces can proportionally constitute a much larger, misleading fraction of the final dataset, ultimately distorting results and leading to false conclusions about the sample's true microbial community [1] [2].

2. What is the fundamental difference between sterilization and disinfection?

- Sterilization is a process that destroys all microbial life, including highly resistant bacterial endospores.

- Disinfection uses liquid chemicals to eliminate virtually all pathogenic microorganisms, but may not destroy bacterial spores [24]. Sterilization (e.g., autoclaving) is the preferred method for decontaminating equipment used in sensitive microbiological work [24].

3. How can I tell if my low-diversity sequencing results are due to contamination? A key indicator is finding microbial taxa in your samples that are also present in your negative controls. These controls—which can include unused swabs, sample preservation fluid, or rinsates from sampling equipment—are essential for identifying contaminants introduced during the sampling and processing workflow [1] [2].

4. What are the most common sources of contamination during sampling? Primary contamination sources include human operators (skin, breath, clothing), the outdoor environment, sampling equipment itself, and reagents. Contamination can occur at any stage, from sample collection and storage to DNA extraction and sequencing [1] [25].

5. Can I rely on ethanol alone to decontaminate my sampling equipment? While 80% ethanol is effective for killing contaminating organisms, it does not reliably remove traces of environmental DNA. For critical low-biomass work, a two-step decontamination is recommended: ethanol to kill organisms, followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., diluted bleach, hydrogen peroxide) to remove residual DNA [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Microbial Diversity

Problem: High Abundance of Human Commensal Bacteria in Samples

- Potential Cause: Contamination from the researcher during sample collection or processing.

- Solution: Implement stricter personal protective equipment (PPE) protocols. Wear gloves, masks, and lab coats. For extremely sensitive samples, consider more extensive PPE like coveralls and shoe covers to limit skin and hair cell shedding [1] [25].

- Preventative Measure: Always include a "sampling control," such as a swab exposed to the air in the sampling environment or an empty collection vessel, to identify human-associated contaminants [1].

Problem: Consistent Detection of the Same Contaminants Across Different Samples

- Potential Cause: Reagent contamination or cross-contamination between samples during processing.

- Solution:

- For reagent contamination: Use dedicated, DNA-free reagents. Include a "negative extraction control" (a blank with no sample) during DNA extraction to identify contaminants from kits and water [1] [12].

- For cross-contamination: Use physical barriers like single-use equipment. If reusing equipment, employ thorough decontamination between samples. Ensure proper layout of the lab workspace to separate "clean" and "dirty" areas [1] [26].

Problem: Unexpected Fungal Signals or High Microbial Diversity in Sterile Samples

- Potential Cause: Environmental contamination from dust, airflow, or improperly maintained equipment.

- Solution: Regularly clean workspaces and equipment. Use HEPA filters in sampling and processing areas. Ensure that heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems are properly maintained to prevent them from becoming a source of microbial contamination [25].

Decontamination Method Comparison

Table 1: Common Decontamination Methods for Laboratory Equipment and Surfaces

| Method | Mechanism | Typical Uses | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoclaving (Wet Heat) [24] | Steam sterilization under high pressure and temperature (e.g., 121°C). | Laboratory glassware, metal tools, biohazardous waste. | Most dependable method for sterilization. Not suitable for heat-sensitive materials. |

| Chemical Disinfection (Liquid) [24] | Halogens (e.g., bleach), alcohols, peroxides disrupt cellular structures. | Benchtop surfaces, non-autoclavable equipment. | Effectiveness depends on concentration, contact time, and target organism. Bleach can be corrosive. |

| UV Radiation [24] | Non-ionizing UV-C light damages microbial DNA. | Reducing airborne microbes in airlocks, biological safety cabinets (with caution). | Organisms must be directly exposed; dust and shadows shield microbes. Requires regular maintenance. |

| Ethanol + DNA Degradation [1] | Ethanol kills cells; DNA degradation solutions (e.g., bleach) remove residual DNA. | Sampling equipment for low-biomass studies. | Two-step process is critical for removing both viable cells and environmental DNA. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Surface Decontamination

This protocol is designed to test the effectiveness of your decontamination procedure on sampling equipment or work surfaces.

1. Objective: To confirm that a decontamination protocol renders a surface free of contaminating microbial DNA.

2. Materials Needed:

- Sterile swabs or wipes

- DNA-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or water

- Reagents for DNA extraction and PCR/sequencing

- Growth media (for viability testing, optional)

3. Procedure:

- Step 1 (Pre-decontamination swab): Swab a defined area (e.g., 10 cm x 10 cm) of the surface to be tested. Use a sterile swab moistened with DNA-free PBS [12].

- Step 2 (Decontaminate): Perform your standard decontamination procedure on the sampled surface (e.g., wipe with 70% ethanol, followed by a DNA removal solution).

- Step 3 (Post-decontamination swab): After the surface has dried, swab the same area with a new sterile swab.

- Step 4 (Process controls): Include a negative control swab that was moistened but not exposed to any surface.

- Step 5 (Analysis): Extract DNA from both swabs and the control. Analyze using high-sensitivity methods like qPCR or 16S rRNA gene sequencing [1] [2].

4. Interpretation:

- Success: The post-decontamination swab shows a microbial profile and DNA concentration similar to or lower than the negative control.

- Failure: The post-decontamination swab shows high DNA yield or distinct microbial taxa (e.g., human skin bacteria) not found in the control, indicating ineffective decontamination.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Effective Decontamination

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-free Swabs [1] | Sample collection from surfaces. | Pre-sterilized and certified DNA-free to prevent introduction of contaminants during sampling. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) [12] | DNA extraction from swabs or filters. | Designed to inhibit humic substances and other PCR inhibitors; commonly used in microbiome studies. |

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) [1] [24] | Chemical disinfection and DNA degradation. | Effective for destroying residual DNA on surfaces. Must be used at an appropriate dilution and may require a rinse with DNA-free water. |

| Ethanol (70-80%) [1] | Chemical disinfection to kill viable cells. | Used as a first step in a two-step decontamination process. Does not remove environmental DNA. |

| Autoclave [24] | Steam sterilization of equipment and waste. | The gold standard for destroying all viable microorganisms, including spores. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) [1] [26] | Gloves, masks, lab coats, coveralls. | Creates a barrier between the researcher and the sample to prevent human-derived contamination. |

Workflow: Equipment Decontamination for Low-Biomass Sampling

Equipment Decontamination Workflow

The Essential Role of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) as a Physical Barrier

In low microbial biomass research, such as studies of human tissues, drinking water, or hyper-arid soils, the microbial DNA from a sample can be so minimal that it approaches the limits of detection [1]. In these sensitive studies, contamination—the introduction of microbial DNA from external sources—can severely distort results, leading to false conclusions about the sample's true microbial diversity [1]. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) serves as a critical physical barrier, not just for protecting the researcher from hazards, but for protecting the sample from contamination by the researcher and the environment [1]. Failure to use PPE correctly is a significant factor that can lead to spurious results, including low microbial diversity, by introducing contaminating DNA.

Troubleshooting FAQs: PPE and Low Microbial Diversity

FAQ 1: Our negative controls consistently show high microbial diversity. Could our PPE be a source of this contamination?

Yes, PPE can be a significant source of contamination. Human skin and hair shed cells and microbial DNA [1]. If PPE is not worn or donned correctly, or if non-sterile PPE is used, these contaminants can enter your samples. To address this:

- Verify Sterility: Use only certified DNA-free, pre-sterilized PPE [1].

- Review Donning Procedures: Ensure staff are trained to don PPE in a clean area without touching the outer surfaces that will face the sample [27].

- Implement Controls: Include PPE controls, such as swabbing the outside of gloves or masks, to identify if they are a contamination source [1].

FAQ 2: We use standard lab coats and gloves, but are still seeing contamination in our low-biomass samples. What are we missing?

Standard lab PPE may be insufficient for low-biomass work. Furthermore, the way PPE is removed can cause contamination. During doffing, the outside surfaces of PPE, which are considered contaminated, can transfer microbes to your hands, clothes, and ultimately to your samples [27].

- Upgrade PPE: Consider more extensive coverage, such as disposable coveralls, shoe covers, and face masks, to minimize skin and clothing exposure [1].

- Focus on Doffing Protocol: Implement and practice a enhanced, step-by-step doffing procedure, potentially under supervision, to minimize self-contamination [27].

- Use a Mirror: Place a full-length mirror in the doffing area to help personnel observe their technique [27].

FAQ 3: Does the type of face mask matter for preventing contamination of samples via aerosols?

Yes, the type of mask significantly impacts contamination control. Surgical masks primarily provide external protection by containing the wearer's droplets, but their loose fit can allow aerosols to escape or enter [28]. In contrast, a well-fitted FFP2/N95 respirator provides superior protection for both the wearer and the sample by filtering a higher percentage of particles [28]. For processes generating aerosols, a respirator is recommended.

FAQ 4: How can we visually train our team on the risks of PPE-related contamination?

Fluorescent powder simulations are an excellent tool for this. By coating a training manikin or surface with fluorescent powder (simulating contaminants) and having personnel don and doff PPE, you can use a UV lamp to visually identify contamination transfer to skin, clothing, or the lab environment [27]. This provides immediate, powerful feedback on protocol breaches.

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating PPE Doffing Contamination

This protocol, adapted from research, uses fluorescent tracing to visualize and minimize contamination during PPE removal [27].

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of a PPE doffing protocol in preventing contamination of the wearer.

Materials:

- Full-body PPE kit (e.g., Coveralls, N95 respirator, goggles, inner and outer gloves, shoe covers)

- Fluorescent powder (e.g., Glo Germ powder)

- Ultraviolet (UV) LED lamp

- Camera capable of high-resolution photography in low light

- A full-length mirror

- Touch-free hand sanitizer dispenser

- Hazardous waste container

Method:

- Preparation: In a preparation room, don the full PPE kit according to your standard protocol.

- Contamination Simulation: Enter the simulation room. Perform a one-minute simulated patient care or sample handling task on a manikin or surface generously coated with fluorescent powder.

- Initial Contamination Check: In a darkened room, use the UV lamp to examine the surfaces of your PPE. Photograph the initial contamination for documentation.

- Doffing with Tracking: Begin the doffing process. After the removal of each PPE item (e.g., outer gloves, gown, goggles), pause and use the UV lamp to check your hands, clothing, and the next item to be removed for the presence of fluorescent powder. Document all findings with photographs.

- Analysis: Categorize any contamination found on the body or clothing by level (e.g., "Negligible," "Noticeable," "Apparent," "Severe") and location (e.g., "hands-fingers," "shirt," "forearms") [27].

Table 1: Categorization of Contamination Levels

| Contamination Level | Description |

|---|---|

| Negligible | Very few fluorescent particles, hard to find. |

| Noticeable | More contaminated than "negligible," easy to find. |

| Apparent | Easily found with enough powder; evident contamination. |

| Severe | Massive contamination with a significant amount of powder. |

Expected Outcome: Studies using this method have found that enhanced, supervised doffing protocols can significantly reduce contamination rates, from over 70% with self-adapted practices down to below 30% [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Contamination Control

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PPE and Contamination Studies

| Item | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| Fluorescent Powder (e.g., Glo Germ) | Visually simulates microbial contaminants under UV light, allowing for qualitative assessment of contamination spread during PPE donning and doffing training [27]. |

| DNA Decontamination Solution (e.g., Bleach) | Used to destroy contaminating DNA on surfaces and non-disposable equipment before sampling. Critical for ensuring sterility as autoclaving alone may not remove cell-free DNA [1]. |

| Pre-sterilized, DNA-free Swabs | For collecting environmental and PPE surface samples as negative controls to monitor background contamination levels throughout an experiment [1]. |

| Touch-free Hand Sanitizer Dispenser | Prevents cross-contamination that can occur from touching the pump of a manual sanitizer dispenser, especially important after removing gloves during the doffing process [27]. |

| Ultraviolet (UV-C) Light Source | Used to sterilize surfaces, equipment, and plasticware by degrading nucleic acids, helping to create a DNA-free work area for processing low-biomass samples [1]. |

| Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH | Fmoc-Orn(Boc)-OH, CAS:109425-55-0, MF:C25H30N2O6, MW:454.5 g/mol |

| Fmoc-Ser-OMe | Fmoc-Ser-OMe, CAS:82911-78-2, MF:C19H19NO5, MW:341.4 g/mol |

PPE Contamination Pathways and Testing

The following diagrams illustrate the critical pathways of contamination related to PPE and a method for testing protocol efficacy.

PPE as a Physical Barrier Against Airborne Transmission

The effectiveness of PPE as a physical barrier extends to blocking airborne transmission pathways, which is crucial for containing aerosols generated during sample processing.

Optimized DNA Extraction Methods for Maximum Yield and Minimal Bias

FAQ 1: My DNA yields from dried blood spots are consistently low. How can I improve recovery?

Low DNA yield from dried blood spots (DBS) is a common issue, often due to the irreversible binding of nucleic acids to the membrane material [29]. The following optimized protocol has been demonstrated to significantly enhance DNA recovery.

- Experimental Protocol: Optimized Spin-Column Extraction for Dried Blood Spots [29]

- Punch: Remove a disc of the dried blood spot from the membrane using a sterile disposable punch.

- Solubilize: Transfer the disc to a microcentrifuge tube. Add an aqueous solubilization buffer and incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation. This step is critical for releasing the DNA from the membrane matrix.

- Lysate Preparation: Proceed with a standard spin-column extraction protocol (e.g., proteinase K digestion, buffer/alcohol binding) using the entire mixture, including the membrane material.

- Elute: Elute the DNA in a low-salt buffer or nuclease-free water.

Table 1: DNA Yield Comparison from Different Blood Sample Formats

| Sample Format | Relative DNA Yield | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Native Liquid Blood | 100% (Baseline) | N/A |

| Dried on Glass Fibre Membrane | 50-60% | Membrane type, optimized solubilization |

| Dried on Cellulose Membrane | 20-30% | Higher nucleic acid retention |

FAQ 2: My metagenomic data shows a strong bias against Gram-positive bacteria. How can I achieve a more balanced lysis?

This bias is typically introduced during the DNA extraction step, as the thick peptidoglycan layer in Gram-positive cell walls is resistant to many lysis methods [30] [31]. Kits lacking mechanical disruption can under-represent Gram-positive taxa by 40-60% compared to Gram-negative bacteria [30].

- Experimental Protocol: Balanced Lysis for Diverse Microbial Communities [30] [31]

- Mechanical Disruption: Use a bead-beating homogenizer. For maximum efficiency, employ a mix of small, dense beads (e.g., 0.1 mm zirconia/silica beads) to disrupt tough cells, alongside larger beads (e.g., 2.8 mm) for macro-scale tissue or biofilm breakdown.

- Enzymatic Lysis Supplement: Combine bead-beating with a multi-enzyme cocktail. A short incubation (15-30 minutes) with a mixture such as lysozyme, mutanolysin, and lysostaphin significantly improves the lysis of Gram-positive bacteria without excessive DNA shearing.

- Chemical Lysis: Use a standard lysis buffer containing SDS.

- Optimized Homogenization: Process samples at a moderate speed (e.g., 5600 RPM for 3 min) to balance complete lysis with DNA integrity. Higher speeds (e.g., 9000 RPM) may be used for exceptionally tough samples but can increase shearing [31].

Table 2: Impact of Lysis Method on Bacterial DNA Recovery

| Lysis Method | Gram-Negative Recovery | Gram-Positive Recovery | Community Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Lysis Only | High | Low (≤60%) | Skewed, inflates Gram-negatives |

| Bead-Beating Only | High | Moderate | Improved, but may under-lyse some Firmicutes |

| Bead-Beating + Enzymatic Cocktail | High | High (Up to 97% lysis efficiency) | Most accurate and balanced |

FAQ 3: I am working with low-biomass, high-host-content samples. How can I reduce host DNA to better sequence the microbiome?

Samples like nasopharyngeal aspirates, skin swabs, or tissue biopsies are challenging due to low microbial DNA and overwhelming host DNA, which consumes sequencing depth [32] [33]. A combination of host DNA depletion and a robust microbial DNA extraction protocol is required.

- Experimental Protocol for Nasopharynx-like Samples [32]

- Host Cell Depletion: Use a commercial host DNA depletion kit, such as MolYsis. These kits selectively lyse mammalian cells and degrade the released DNA with a DNase, while leaving microbial cells intact.

- Microbial DNA Extraction: After depletion, pellet the intact microbial cells. Perform DNA extraction using a kit validated for Gram-positive bacteria, such as the MasterPure Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit. This ensures lysis of all remaining microbial types.

- Include Controls: Always process negative controls (e.g., empty swabs, blank buffers) to identify contaminating DNA from reagents or the environment, which is a major concern in low-biomass studies [1] [32].

This combined "Mol_MasterPure" protocol has been shown to reduce host DNA content from >99% to as low as 15% in some samples, increasing usable bacterial reads by over 1,700-fold [32].

FAQ 4: My soil/sediment DNA extracts are contaminated with PCR inhibitors. What is the best purification method?

Soil and sediment samples are notorious for co-extracting humic acids and other substances that inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions [34]. The purification step is as critical as the extraction itself.

- Experimental Protocol: Inhibitor Removal for Soil DNA [34]

- Optimized Extraction: Perform a brief, low-speed bead mill homogenization in a phosphate-buffered SDS-chloroform mixture. This maximizes cell lysis while minimizing DNA shearing and the release of inhibitors.

- Purification: Apply the crude DNA extract to a Sephadex G-200 spin column. This gel filtration method was found to be superior for removing PCR-inhibiting substances while minimizing DNA loss compared to silica binding or precipitation methods [34].

- Quality Check: Assess DNA purity spectrophotometrically (A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios) and confirm the absence of inhibitors via a spike-in PCR assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Unbiased DNA Extraction

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| MolYsis Basic5 | Selective depletion of host DNA from samples | Crucial for low-biomass, high-host-content samples like nasopharyngeal aspirates [32]. |

| MasterPure Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit | Robust lysis and purification of DNA from difficult-to-lyse bacteria | Effective for achieving balanced lysis in diverse communities; works well post-host-depletion [32]. |

| Sephadex G-200 Resin | Gel filtration medium for purifying DNA from PCR inhibitors like humic acids | Ideal for purification of DNA from complex environmental samples like soil and sediment [34]. |

| Zirconia/Silica Beads (0.1 mm & 2.8 mm mix) | Mechanical disruption of microbial cell walls | A mix of small and large beads ensures efficient lysis across diverse bacterial morphologies [30]. |

| MetaPolyzyme (Lysozyme, Mutanolysin, etc.) | Enzymatic cocktail for digesting peptidoglycan in bacterial cell walls | Supplement to bead-beating to ensure complete lysis of Gram-positive bacteria [30]. |

| Fmoc-N-Me-Thr(tBu)-OH | Fmoc-N-Me-Thr(tBu)-OH, CAS:117106-20-4, MF:C24H29NO5, MW:411.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-Thr-OH | Fmoc-Thr-OH, CAS:73731-37-0, MF:C19H19NO5, MW:341.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Designing a Multi-Modal Cultivation Strategy to Capture Diversity

FAQs: Troubleshooting Low Microbial Diversity

Why is my cultivated microbial diversity much lower than my culture-independent sequencing indicates? This is a common challenge, often referred to as the "great plate count anomaly." Even with extensive cultivation efforts, traditional methods may recover less than 40% of the species detected by direct metagenomic sequencing [35]. This occurs because a significant portion of environmental microbes have fastidious and unknown growth requirements that are not met by standard laboratory media. To address this, implement a strategy using multiple, diverse culture media and conditions to target a broader spectrum of microorganisms [36] [35].

What are the key experimental factors I can adjust to improve diversity recovery? The most critical factors are the variety of growth media, incubation atmospheres, and sample processing techniques. Using 12 different media types, for example, has been shown to capture distinct subsets of the microbial community, significantly increasing the total recovered diversity [35]. Furthermore, always include both aerobic and anaerobic incubation, as obligate anaerobes constitute a major portion of uncultured diversity.

My cultivation fails due to contamination. How can I prevent this? Maintaining sterile conditions is paramount. Common sources of error include improper use of laminar flow hoods and biosafety cabinets. Ensure all equipment, like autoclaves, is functioning correctly. For training, utilize resources from the American Biological Safety Association (ABSA) and practice sterile techniques with relevant virtual lab simulations [37].

How do I know if my diversity estimates are accurate? Ensure you are using appropriate alpha diversity metrics and interpreting them correctly. Standardizing your approach is key. A comprehensive analysis recommends using a core set of metrics that collectively assess different aspects: richness (e.g., Chao1), phylogenetic diversity (Faith PD), entropy (Shannon), and dominance (e.g., Simpson) [38]. Relying on a single metric can provide a biased view of the true diversity in your samples.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Diversity Metrics

Issue: Difficulty interpreting or comparing alpha diversity values from different experiments.

Solution: Standardize your alpha diversity analysis pipeline.

Categorize Your Metrics: Group alpha diversity metrics into four complementary categories as proposed by recent guidelines [38]:

- Richness: Estimates the number of distinct species (e.g., Chao1, ACE).

- Phylogenetic Diversity: Incorporates evolutionary relationships (e.g., Faith PD).

- Information Metrics: Describe uncertainty in predicting identity (e.g., Shannon, Brillouin).

- Dominance/Diversity Metrics: Describe the distribution of abundances (e.g., Simpson, Berger-Parker).

Report a Comprehensive Set: Do not rely on a single metric. Report at least one metric from each category to gain a holistic understanding of your samples' diversity [38].

Understand Key Influences: Be aware that some metrics are heavily influenced by specific factors. For instance, the Robbins metric is highly dependent on the number of singletons (ASVs with only one read) in your data, which can be affected by your bioinformatics pipeline [38].

Problem: Failure to Cultivate "Microbial Dark Matter"

Issue: Standard media and conditions fail to grow the majority of target microbes, particularly from complex samples like soil or gut.

Solution: Employ advanced cultivation strategies that mimic the natural environment.

Use Co-cultivation: Many uncultured microbes depend on metabolic byproducts or signaling molecules from other species. Cultivating them in pairs or consortia can stimulate growth [36].

Leverage Environmental Simulators: Utilize devices like diffusion chambers or microfluidic chips that allow nutrients and signals from the natural environment to reach the cells while containing them for growth [36].

Modify Media Composition:

- Add Growth Factors: Incorporate specific compounds like zincmethylphyrins, coproporphyrins, or short-chain fatty acids to meet unknown metabolic needs [36].

- Craft Selective Media: Use inhibitors to suppress fast-growing competitors and allow slow-growers to emerge. For example, diuron has been used to inhibit oxygenic phototrophs to isolate novel Chloroflexota [36].

- Mimic Physicochemical Conditions: Adjust pH, temperature, and pressure to match the source environment, which is crucial for isolating novel archaea and bacteria from extreme environments [36].

Problem: Low-Abundance Taxa Are Missing from Cultures

Issue: Cultivation efforts are dominated by a few fast-growing species, missing the "microbial underdogs" that may be ecologically or functionally important.

Solution: Implement strategies specifically designed to capture low-abundance taxa.

Avoid Filtering Low-Abundance Data: In sequencing analysis, do not automatically filter out low-abundance taxa during bioinformatics processing, as this can obscure keystone species [39].

Apply Dilution-to-Extinction: This method dilutes the dominant members of a community, reducing competition and allowing rare species to grow. Studies have shown that losing these low-abundance bacteria through dilution can significantly alter functional outcomes in model hosts [39].

Utilize High-Throughput Techniques: Combine cultivation in multiple micro-environments (e.g., using 96-well plates) with culture-enriched metagenomic sequencing (CEMS). CEMS sequences all colonies from a plate without manual picking, efficiently capturing rare, culturable organisms that are often missed by experienced colony picking (ECP) [35].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS)

This protocol leverages high-throughput metagenomic sequencing of entire culture plates to maximize the detection of culturable microbes, including those an researcher might overlook [35].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Preparation:

- Suspend 0.5 g of sample (e.g., stool, soil) in 4.5 mL of 0.85% NaCl solution.

- Prepare a dilution series from 10â»Â³ to 10â»â· to isolate individual colonies and reduce competition.

Multi-Modal Cultivation:

- Plate 200 µL of each dilution onto 12 different types of solid media. These should include [35]:

- Nutrient-Rich Media (e.g., LGAM, PYG, Gifu Anaerobic Medium (GAM)).

- Oligotrophic Media (e.g., 1/10 GAM, low-nutrient agar).

- Selective Media (e.g., with bile salts, high salt, or antibiotics).

- For each medium, incubate one set of plates anaerobically (in a chamber with 95% N₂, 5% H₂) and another set aerobically at 37°C for 5-7 days [35].

- Plate 200 µL of each dilution onto 12 different types of solid media. These should include [35]:

Culture Harvesting and DNA Extraction:

- After incubation, add 1 mL of 0.85% NaCl solution to each plate.

- Use a sterile cell scraper to harvest all biomass from the plate's surface, combining colonies from all dilutions of the same medium and atmosphere.

- Centrifuge the harvested suspension to pellet the cells.

- Extract metagenomic DNA from the pellet using a standardized kit (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit), following the manufacturer's instructions [35].

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing on an Illumina platform.

- Analyze the data to determine the taxonomic composition and functional potential of the cultured community. Calculate Growth Rate Index (GRiD) values to identify the optimal medium for specific bacterial taxa [35].

Protocol 2: Advanced Environmental Cultivation

This protocol outlines strategies for cultivating microbes from extreme or specialized environments, focusing on mimicking natural conditions [36].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

Enrichment Strategies:

- Selective Nutrients: Add specific substrates from the target environment. For example, use manganese carbonate to enrich for manganese-oxidizing bacteria like Candidatus Manganitrophus noduliformans [36].

- Physicochemical Conditions: Tailor pH, temperature, and salinity to match the source habitat. This is critical for isolating novel archaea from hot springs or extreme environments [36].

- Selective Suppression: Use inhibitors to suppress dominant groups. For instance, diuron can be used to inhibit oxygenic phototrophs, allowing novel non-oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria like certain Chloroflexota to grow [36].

In Situ Cultivation and Devices:

- Diffusion Chambers: Place inoculated chambers back into the natural environment, allowing chemical exchange while containing cells.

- Bio-Devices: Use continuous-flow cell systems or biofilm reactors to provide a stable, nutrient-controlled environment that supports slow-growing, syntrophic microbes, as demonstrated by the cultivation of Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum [36].

Isolation and Purification:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Microbial Diversity Assessment Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Pros | Cons | Typical Species Recovery (vs. CIMS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-Independent Metagenomic Sequencing (CIMS) [35] | Direct DNA sequencing from sample | Captures full genetic potential; detects unculturable taxa | Cannot distinguish live/dead; functional role uncertain | Reference (100%) |

| Experienced Colony Picking (ECP) [35] | Manual selection and isolation of colonies | Yields pure strains for functional studies | Labor-intensive; misses inconspicuous/rare colonies | Low (Substantial missed detection) |

| Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS) [35] | Metagenomic sequencing of all grown biomass from a plate | High-throughput; captures rare culturable taxa; provides GRiD data | Does not provide pure isolates | High (~36.5% of species, with low overlap to CIMS) |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Modal Cultivation

| Reagent / Material | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Gifu Anaerobic Medium (GAM) [35] | Nutrient-rich media | General growth of fastidious anaerobic bacteria from gut and environmental samples. |

| PYG Broth / Agar [35] | Nutrient-rich media | Cultivation of a wide range of anaerobic bacteria, particularly from the gut. |

| 1/10 GAM [35] | Oligotrophic media | Promotes growth of slow-growing or low-abundance bacteria outcompeted in rich media. |

| Diffusion Chambers [36] | In situ cultivation device | Allows chemical exchange with the natural environment to provide unknown growth factors. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit [12] | DNA extraction kit | Efficiently lyses microbial cells and purifies DNA from complex, difficult-to-lyse samples like soil. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) [12] | Buffer | Used for moistening swabs and suspending samples during collection and processing. |

| FloqSwabs [12] | Sample collection | Sterile swabs for effective microbial collection from surfaces. |

Diagnosing and Solving Common Pitfalls in Diversity Analysis

A practical FAQ for researchers troubleshooting low microbial diversity in their samples.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

My microbial diversity is unexpectedly low. What are the first steps I should take?

Low microbial diversity can often be a symptom of contamination or technical artifacts. Your initial investigation should focus on the two most common culprits: sample processing contaminants and sequencing errors.

First, review your experimental controls. Reagent-only negative controls are essential for identifying contaminants introduced from DNA extraction kits or PCR reagents [40]. Analyze these controls alongside your samples—any taxa present in both are likely contaminants. Second, consider sequencing errors, which can artificially reduce diversity by distorting the true abundance of species, particularly rare taxa [41].

We recommend a step-by-step approach, visualized in the workflow below, to systematically rule out these issues.

How can I tell if my samples are cross-contaminated, and what tools can I use to fix it?

Sample cross-contamination occurs when DNA from one sample inadvertently leaks into another. This can happen during nucleic acid extraction or library preparation. Detection relies on analyzing patterns that deviate from expectations.

For studies involving paired samples (e.g., tumor-normal), you can screen for anomalies by examining mutation abundances. A significant shift in the correlation of mutation profiles or an abnormal distribution of heterozygous alleles between paired samples can indicate contamination or even sample mislabeling [42].

In microbiome studies, the focus shifts to identifying unexpected taxa. The following tools are commonly used for contamination detection and removal:

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastQ Screen [43] | Contamination Screening | Aligns reads to multiple genomes; provides visual reports | Initial, user-friendly screening of contamination sources |

| DeconSeq [43] | Automated Removal | Identifies and removes contaminating reads automatically | Projects where the contaminant genome is known |

| Kraken [43] | Taxonomic Classification | Ultra-fast k-mer based classification against a database | Metagenomic studies to identify all contaminant species |

| BBSplit [43] | Read Sorting | Splits sequencing reads by alignment to multiple genomes | Complex samples with multiple potential contaminant sources |

My negative controls are clean, but I still suspect technical issues. What's next?

If your controls are clear, the next step is to investigate PCR amplification errors during library preparation. These errors are a major technical artifact that can severely skew diversity estimates.

During PCR, artificial sequences are created and later clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs). These can be mistaken for rare species, leading to an overestimation of rare taxa and a distorted view of true community structure [41]. The table below summarizes the impact and solutions for this issue.

| Aspect of Impact | Consequence | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Singletons (Unique Sequences) | Artificial inflation of rare species; single sequences can be misclassified as new species [41]. | Use denoising algorithms like DADA2 or UNOISE3 to distinguish true biological variants from errors [41]. |

| Diversity Indices | Systemic bias in core metrics like the Shannon Diversity Index [41]. | Apply a combination of bioinformatic filtering and statistical modeling for correction [41]. |

| Species Richness | Total species count can be overestimated by up to 300% [41]. | Employ the "Missing Link" model for full-abundance error correction, which can reduce estimation error to ±12% [41]. |

What are the best practices for visualizing my data to avoid misinterpretation?

Proper data visualization is critical for accurate interpretation and communication of results. Adhering to community standards helps prevent misunderstandings.

- Avoid Stacked Bar Charts: While popular for showing community composition, stacked bar charts are not recommended. They fail to show data distribution and standard deviation, and low-abundance taxa are often not visible [40].

- Recommended Plots: Use box plots or violin plots to represent alpha diversity metrics (e.g., Shannon Index) across sample groups. These plots effectively display the data distribution, making comparisons more robust [40].

- Color Palette: Always use a colorblind-friendly (CVD-friendly) palette to ensure your findings are accessible to all audiences [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Investigation |

|---|---|

| Negative Control Samples | Contains only the reagents (e.g., from DNA extraction kits) used in your workflow. Serves as a baseline to identify contaminating DNA present in your reagents [40]. |

| Mock Community Standards | A synthetic sample comprising DNA from known microorganisms. Used as a positive control to validate your entire workflow, from DNA extraction to bioinformatic analysis, and to calibrate error rates [40]. |

| DADA2 / UNOISE3 | Bioinformatic tools (algorithms) used in the data preprocessing stage. They correct amplicon sequencing errors and remove chimeric sequences, leading to a more accurate table of biological sequences [41]. |

| Statistical Error Models (e.g., Missing Link Model) | Advanced statistical models, such as the 2024 "Missing Link" model, which uses a Bayesian network to correct for sequencing errors across the full abundance range of species, significantly improving richness estimates [41]. |

| Fmoc-Phe(2-Cl)-OH | Fmoc-2-chloro-L-phenylalanine|Building Block |

Experimental Protocol: Contamination Screening with Negative Controls

Purpose: To identify and filter out contaminating DNA sequences introduced during wet-lab procedures.

Methodology:

- Sample Processing: In parallel with your experimental samples, process a reagent-only negative control. This sample should contain all the reagents from your DNA extraction kit but no biological material [40].

- Sequencing: Sequence the negative control alongside your experimental samples on the same sequencing run to ensure identical technical conditions.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process the sequencing data through your standard pipeline (e.g., QIIME 2, mothur) to assign taxonomy to all sequences.

- Generate a feature table that includes the counts of all Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or OTUs in each sample and the negative control.

- Contaminant Identification: Use a contamination screening tool or a simple prevalence-based method. The core principle is that sequences found in the negative control are very likely to be contaminants. A common practice is to remove any ASV/OTU that has a higher relative abundance in the control than in the experimental samples, or that appears in a majority of controls.

- Data Filtering: Create a "filtered feature table" by subtracting the identified contaminant sequences from your experimental samples. All subsequent diversity and statistical analyses should be performed on this filtered table.

This systematic approach to contamination investigation will help you distinguish true biological signals from technical noise, leading to more robust and reliable conclusions in your microbial ecology research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Low Microbial Diversity

Why is my microbial diversity in culture so low compared to my sequencing data?

This is a common challenge known as the "great plate count anomaly," where the vast majority of environmental microorganisms resist cultivation on standard laboratory media [44]. The primary reasons include:

- Non-representative media: Standard laboratory media often do not replicate the natural nutritional environment, failing to support the growth of fastidious organisms [44] [45].

- Lack of environmental cues: Microbes in their habitat rely on complex signals, growth factors, and interactions with other organisms that are absent in a standard Petri dish [46].

- Oxygen sensitivity: Many environmental microbes, especially gut microbiota, are strict anaerobes and require specialized equipment and protocols to be cultivated successfully [44].

- Overgrowth by fast-growing species: A few fast-growing generalists (e.g., Bacillus spp. on R2A medium) can quickly dominate plates, obscuring slow-growing, rare species [45] [47].

How can I improve the diversity of my isolates?

The key is to move beyond a single, standard cultivation condition. A multi-pronged strategy that incorporates environmental simulation and high-throughput techniques is vastly more effective.