Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer: Techniques, Optimizations, and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT), a technique that leverages the innate ability of spermatozoa to bind, internalize, and deliver exogenous DNA into oocytes during...

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer: Techniques, Optimizations, and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT), a technique that leverages the innate ability of spermatozoa to bind, internalize, and deliver exogenous DNA into oocytes during fertilization. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational mechanisms of sperm-DNA interaction, detail established and cutting-edge methodological protocols, and present strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing transfer efficiency. The content further validates the technology through comparative analysis with other transgenic methods and discusses its significant implications for creating large animal models, advancing xenotransplantation research, and exploring future gene therapy avenues.

The Science Behind SMGT: Unraveling the Mechanisms of Sperm-DNA Interaction

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) is a transgenic technique that leverages the innate ability of sperm cells to bind, internalize, and transport exogenous DNA into an oocyte during fertilization, leading to the production of genetically modified animals [1]. This methodology serves as a potent biotechnological tool for generating animals valuable for basic research as well as biomedical, veterinary, and agricultural applications [2]. The core principle of SMGT utilizes the sperm cell as a natural vector for genetic material, providing an alternative to more technically demanding and expensive methods like pronuclear microinjection [1] [3]. Since its initial report in 1989, SMGT has been applied across a variety of animal species, including mammals, birds, and fish, indicating its broad applicability within the Metazoan kingdom [1]. Despite its potential, the technique is accompanied by controversy and variable success rates, largely attributable to natural biological barriers that have evolved to prevent the inadvertent uptake of foreign DNA [1].

Core Mechanisms of DNA Uptake and Transport

The process by which sperm cells acquire and deliver exogenous DNA is not a random event but a regulated sequence involving specific molecular interactions.

DNA Binding and Internalization

The journey of exogenous DNA begins with its binding to the cell membrane of the sperm head. This interaction is specifically mediated by DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) present on the sperm surface [1]. The presence of these proteins suggests a selective mechanism for DNA uptake. However, in mammals, this process is naturally inhibited by a factor found in seminal plasma. This inhibitory factor causes the DBPs to lose their ability to bind exogenous DNA, thus acting as a primary barrier against foreign genetic material [1]. Consequently, for SMGT to be successful, the seminal fluid must be removed from sperm samples through extensive washing immediately after ejaculation [1]. Once the inhibitory factor is eliminated and DNA binding occurs, the exogenous genetic material is translocated into the sperm cell interior.

Endogenous Machinery and Retrotransposon Activity

Recent insights into the mechanism challenge the traditional view of sperm as metabolically inert cells. Studies indicate that the binding of exogenous DNA triggers otherwise repressed enzymatic functions within the sperm [4]. Among these, a significant discovery is the activity of an endogenous retrotransposon-encoded reverse transcriptase. This enzyme can reverse transcribe exogenous RNA molecules into cDNA copies, which are then delivered to the embryo during fertilization [4]. The resulting reverse-transcribed molecules are characterized as low-copy, extrachromosomal structures that are mosaic distributed among tissues, transcriptionally competent, and capable of inducing phenotypic variations. This has led to the proposal that SMGT can be viewed as a retrotransposon-mediated phenomenon, positioning the sperm's endogenous retrotransposon machinery as a novel source of genetic variability [4].

Natural Barriers and Controversy

The inherent ability of sperm to take up foreign DNA is a subject of scientific skepticism, primarily because evolutionary chaos could ensue if sperm cells readily acted as vectors for any exogenous DNA they encountered [1]. Nature has, therefore, established robust barriers to minimize such unintentional genetic interactions. The two identified primary protections are:

- The inhibitory factor in seminal fluid that prevents DNA binding [1].

- An endogenous sperm nuclease activity that is activated upon interaction with foreign DNA molecules [1]. These barriers ensure that not every fertilization event is potentially mutagenic. The inconsistency in SMGT experimental outcomes across different laboratories is often attributed to the variable efficacy of these natural protections, with successful SMGT potentially representing instances where these barriers were overcome [1].

Quantitative Data on SMGT Efficiency

The efficiency of SMGT varies significantly across species and experimental protocols. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from published studies.

Table 1: Efficiency Metrics of Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer in Different Species

| Species | Method | Transgene Transmission Rate (F0) | Germline Transmission (F1) | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pig | Linker-Based SMGT (LB-SMGT) | 37.5% of offspring | Demonstrated | High-efficiency generation of transgenic pigs. | [5] |

| Mouse | Linker-Based SMGT (LB-SMGT) | 33% of offspring | Demonstrated | High-efficiency generation of transgenic mice. | [5] |

| Pig | Standard SMGT | Up to 80% phenotype modification in some experiments | ~25% of studies showed F1 transmission | High variability in success rates. | [1] |

| Goat | Electroporation-aided TMGT | Production of one transgenic kid from 9 matings | Not assessed | First successful report in goats; no detrimental effects on sperm quality. | [6] |

| Mouse | MBCD-SMGT with CRISPR/Cas9 | Successful generation of targeted mutant blastocysts and mice | Not assessed | Validated targeted indels in embryos and offspring. | [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for two primary approaches to SMGT: the basic protocol utilizing sperm incubated in vitro and a more advanced method involving testis-mediated gene transfer.

Protocol 1: Standard Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer

Principle: This method relies on the spontaneous uptake of exogenous DNA by washed spermatozoa, which are then used for in vitro fertilization (IVF) to produce genetically modified embryos [1] [2].

Procedure:

- Sperm Collection and Washing: Collect sperm from the epididymis or ejaculate. It is critical to remove the seminal plasma thoroughly through extensive washing in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS or HTF medium) to eliminate the inhibitory factor that blocks exogenous DNA binding [1].

- Sperm Incubation with Exogenous DNA: Incubate the washed, motile sperm cells with the prepared exogenous DNA construct. A common approach is to resuspend approximately 1-5 x 10^7 sperm cells in a medium containing 20-100 ng/µL of the linearized plasmid DNA for 30-60 minutes at room temperature or 37°C [7] [2].

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): Use the DNA-loaded sperm cells to fertilize mature oocytes in vitro under standard conditions for the species of interest [2].

- Embryo Culture and Transfer: Culture the resulting zygotes to the desired embryonic stage (e.g., blastocyst) in vitro. Subsequently, transfer the embryos into synchronized surrogate females to come to term [6].

- Genotyping and Analysis: Screen the resulting offspring (F0 generation) for the presence and integration of the transgene using PCR, Southern blot, and expression analyses. Assess germline transmission by breeding F0 animals and screening the F1 progeny [5].

Protocol 2: Electroporation-Aided Testis-Mediated Gene Transfer (TMGT)

Principle: This in vivo technique involves the direct injection of a transgenic construct into the testicular interstitium, followed by electroporation to facilitate gene transfer into spermatogenic cells, including spermatogonial stem cells [6].

Procedure:

- Optimization of Injection Parameters:

- Volume: Determine the maximum injectable volume for the testis. For pre-pubertal goats, this is 1.0 mL, and for adult goats, 1.5 mL [6].

- DNA Concentration: Standardize the DNA concentration. A concentration of 1 µg/µL of linearized plasmid is optimal for efficient transfection of testicular cells [6].

- In Vivo Gene Transfer:

- Anesthetize the male animal and surgically expose the testes.

- Using a sterile syringe, inject the optimized volume of DNA solution (e.g., pIRES2-EGFP plasmid at 1 µg/µL) directly into the testicular interstitium [6].

- Immediately after injection, apply electroporation to the testis using optimized conditions (e.g., voltage, pulse duration, and intervals) to enhance DNA uptake by the germ cells [6].

- Recovery and Sperm Analysis:

- Allow the animal to recover. The transgene expression in spermatogenic cells can be assessed as early as 21 days post-electroporation via immunohistochemistry, qPCR, and Western blot [6].

- Collect semen samples periodically (e.g., day 60 and 120 post-treatment) to analyze sperm for the presence and integration of the transgene using qPCR and fluorescence microscopy. This protocol has been shown to not alter seminal parameters like motility, viability, or fertilization capacity [6].

- Production of Transgenic Offspring:

- Use the sperm from the transfected male (pre-founder) for natural mating or IVF. In the cited goat study, natural mating of a pre-founder buck resulted in the birth of a transgenic kid, confirming the successful integration of the transgene into the germline [6].

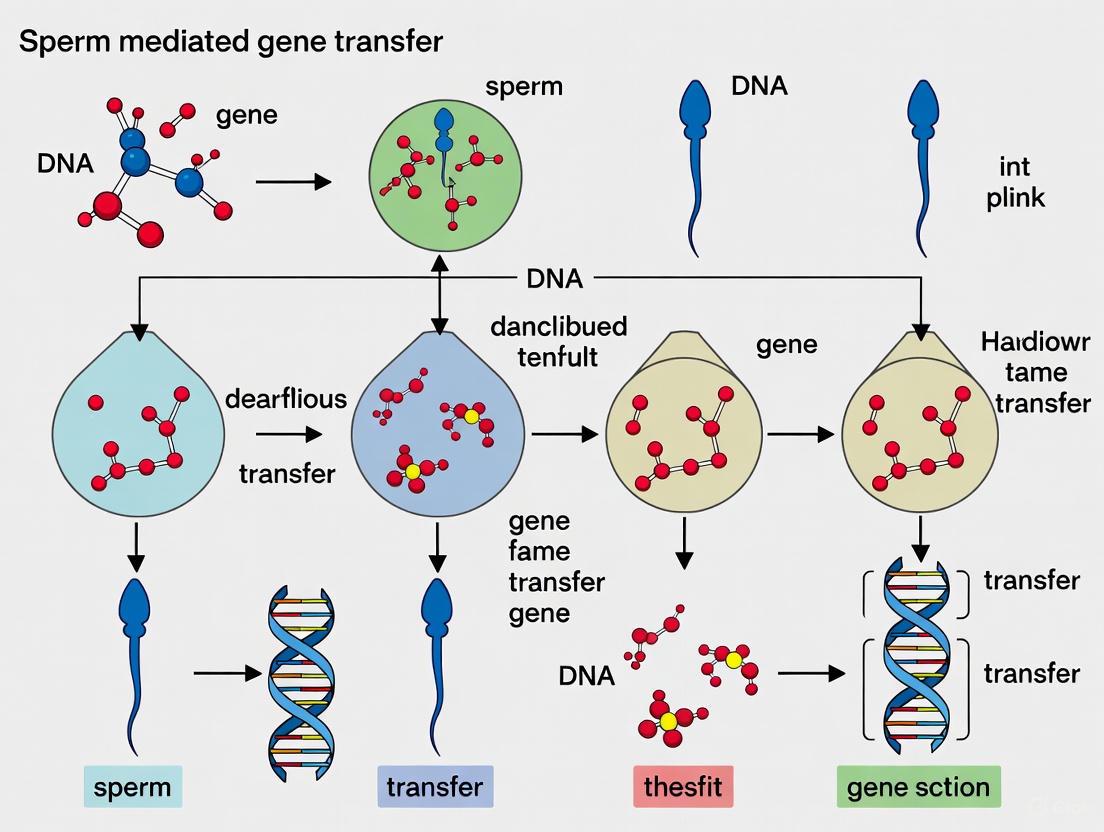

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT), outlining both the standard in vitro protocol and the Testis-Mediated Gene Transfer (TMGT) in vivo approach. Key optimization steps are indicated with dashed lines.

Advanced Applications: SMGT in the CRISPR/Cas9 Era

The advent of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing has opened new avenues for SMGT, leading to the development of techniques like sperm-mediated gene editing (SMGE). A prominent advancement is the MBCD-SMGE technique, which optimizes the uptake of the CRISPR/Cas9 system into sperm cells [7].

Principle: Treatment of sperm with Methyl β-Cyclodextrin (MBCD), a cyclic glucose heptamer, removes cholesterol from the sperm membrane. This process increases membrane fluidity, induces a premature acrosomal reaction, and elevates extracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), collectively enhancing the internalization of exogenous DNA, including CRISPR/Cas9 constructs [7].

Procedure:

- Sperm Treatment: Incubate washed sperm in a protein-free medium (e.g., c-TYH) supplemented with MBCD (e.g., 0.75-2 mM) in the presence of the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid (e.g., 20 ng/µL) for 30 minutes [7].

- Assessment: Evaluate functional sperm parameters (motility, viability), extracellular ROS, and the copy number of internalized plasmids per sperm cell.

- IVF and Analysis: Perform IVF using the transfected sperm. The technique has been validated to produce a higher rate of GFP-positive blastocysts and, ultimately, targeted mutant mice with specific indels confirmed [7].

Figure 2: Mechanism of the MBCD-SMGE technique. MBCD treatment modifies the sperm membrane biophysics and biochemistry, leading to enhanced CRISPR/Cas9 system uptake and the generation of targeted mutant animals.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents and their critical functions in SMGT experiments, as derived from the cited protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer

| Reagent / Material | Function in SMGT Protocol | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl β-Cyclodextrin (MBCD) | Cholesterol removal from sperm membrane; enhances exogenous DNA/CRISPR complex uptake by increasing membrane fluidity and inducing acrosome reaction. | Used at 0.75-2 mM in c-TYH medium for MBCD-SMGE [7]. |

| Linker Protein (e.g., mAb C) | Monoclonal antibody that binds to sperm surface antigen and, via ionic interaction, acts as a cross-linker to specifically tether exogenous DNA to sperm cells. | Used in Linker-Based SMGT (LB-SMGT) to significantly increase DNA binding to sperm in multiple species [5]. |

| Electroporation Apparatus | Application of electrical pulses to create transient pores in cell membranes, facilitating DNA entry into sperm (in vitro) or testicular cells (in vivo). | Used for in vivo gene transfer after intratesticular injection in TMGT [6]. |

| Sperm Washing Media (e.g., PBS, HTF) | Removal of inhibitory seminal plasma components that prevent exogenous DNA binding to sperm surface DNA-Binding Proteins (DBPs). | Essential first step in all standard SMGT protocols [1] [7]. |

| Transgenic Constructs (Plasmids) | Vector carrying the gene of interest (e.g., reporter genes like EGFP, therapeutic genes like hDAF) or the CRISPR/Cas9 system for gene editing. | pIRES2-EGFP for tracking transfection [6]; pCAG-eCas9-GFP for gene editing [7]. |

| In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) Media | Supports the process of fertilizing oocytes with DNA-loaded sperm and subsequent culture of the resulting embryos. | Media like HTF for fertilization and mKSOM for embryo culture [6] [7]. |

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) is a transgenic technique that utilizes the innate ability of sperm cells to bind, internalize, and transport exogenous DNA into an oocyte during fertilization to produce genetically modified animals [1]. The core of this process hinges upon specific molecular interactions, primarily between exogenous DNA and DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) present on the sperm cell membrane [1] [4]. These interactions are not random events but are instead highly regulated processes that determine the efficiency of DNA uptake and integration [4]. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for optimizing SMGT protocols, enhancing its reliability for generating transgenic animal models for biomedical, agricultural, and veterinary research, and exploring its potential applications in gene therapy [1] [8]. This application note details the key molecular mechanisms, provides quantitative insights, and outlines standardized experimental protocols for investigating DNA-binding protein interactions in SMGT.

Key Molecular Mechanisms of DNA-Sperm Interaction

The journey of exogenous DNA from the extracellular environment into the sperm nucleus involves a coordinated series of events mediated by specific proteins. The traditional view of metabolically inert spermatozoa has been challenged by findings showing that the binding and internalization of exogenous DNA are active, regulated processes [4].

The Central Role of DNA-Binding Proteins (DBPs)

The initial attachment of exogenous DNA to the sperm cell membrane is facilitated by DBPs located on the surface of the sperm head [1]. Recent research has identified specific proteins that are critical for this function.

Table 1: Key Proteins in Sperm-Mediated DNA Binding and Uptake

| Protein Name | Location | Function in SMGT | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| IAM38 (Inner Acrosomal Membrane protein 38) | Sperm plasma membrane | Primary receptor for binding exogenous DNA; forms a complex with CD4 for DNA transport [9]. | Blocking IAM38 with antibodies significantly impairs DNA-binding capacity and reduces EGFP-positive embryos [9]. |

| CD4 | Sperm plasma membrane | Cooperates with IAM38; facilitates the uptake and transportation of bound DNA into the sperm nucleus [9]. | Blocking CD4 decreases DNA uptake without affecting initial binding, and reduces EGFP-positive blastocysts [9]. |

| Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II | Sperm plasma membrane | Implicated in the interaction between sperm cells and exogenous DNA [9]. | Early studies suggested a role in the DNA interaction mechanism [9]. |

| Endogenous Reverse Transcriptase | Intracellular | Reverse transcribes exogenous RNA into cDNA, which can be delivered to embryos [4]. | The generated cDNA is propagated as extrachromosomal structures and can induce phenotypic variations [4]. |

The identification of IAM38 and CD4 provides a more detailed molecular understanding of the SMGT mechanism. The process begins with foreign DNA binding directly to the transmembrane protein IAM38. This DNA/IAM38 complex then interacts with CD4, forming a larger complex that completes the transportation of the exogenous DNA into the nucleus of the sperm [9].

Natural Barriers and Regulatory Controls

Nature has evolved protective barriers to prevent the unintentional uptake of foreign DNA, which contributes to the variable efficiency of SMGT. Two primary barriers have been identified [1]:

- Seminal Fluid Inhibitory Factor: A factor present in mammalian seminal fluid blocks the binding capacity of DBPs. For successful SMGT, this necessitates the extensive washing of sperm samples immediately after ejaculation to remove the seminal plasma [1] [9].

- Sperm Endogenous Nuclease Activity: An endogenous nuclease activity is triggered when sperm cells interact with foreign DNA molecules, likely as a defense mechanism to degrade the external genetic material [1].

A Retrotransposon-Mediated Model

Emerging evidence suggests that SMGT is not a simple mechanical transfer but a retrotransposon-mediated phenomenon. The binding of exogenous DNA or RNA sequences can trigger enzymatic functions, including an endogenous retrotransposon-encoded reverse transcriptase activity [4]. This enzyme can reverse transcribe exogenous RNA molecules into cDNA copies. These cDNA molecules are then delivered to the embryo upon fertilization, where they can be propagated as low-copy, extrachromosomal structures that are mosaic distributed, transcriptionally competent, and can even be sexually transferred to subsequent generations in a non-Mendelian fashion [4]. This reveals that the sperm endogenous retrotransposon machinery can be a novel source of genetic information.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential signaling pathway of exogenous DNA interaction with sperm membrane proteins, culminating in nuclear entry and potential retrotranscription.

Quantitative Data on SMGT Efficiency

The efficiency of SMGT is variable across species and experimental conditions. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from the literature, highlighting both the potential and the challenges of the technique.

Table 2: SMGT Efficiency in Mouse Models

| Parameter | Value | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Transgenic Success Rate | 7.4% of total fetuses (13 out of 75 experiments) | Large, collaborative study on mouse eggs [10]. |

| High-Efficiency Clustering | >85% of offspring in 5 experiments | Success was clustered in a small number of runs, indicating influential variables [10]. |

| Number of Non-Productive Experiments | 62 experiments produced no transgenic offspring | Highlights the inconsistency of early SMGT protocols [10]. |

Table 3: Impact of Protein Blocking on DNA Transfer Efficiency

| Experimental Condition | Effect on DNA Binding | Effect on DNA Uptake | Effect on Embryo Development | Model System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAM38 Blocking | Significantly impaired | Not explicitly measured | Decreased EGFP-positive embryos and blastocysts | Rabbit sperm [9] |

| CD4 Blocking | No significant influence | Decreased | Decreased EGFP-positive embryos and blastocysts | Rabbit sperm [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Identifying DNA-Binding Proteins (DBPs) in Sperm

This protocol is adapted from methods used to identify IAM38 and CD4 in rabbit sperm [9].

Objective: To isolate and identify sperm membrane proteins responsible for binding exogenous DNA.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) | Separates native proteins and protein-DNA complexes based on charge and size without denaturing them. |

| Coomassie Blue Staining | A standard dye-based method for visualizing protein bands in a gel. |

| Mass Spectrometry Analysis | Identifies proteins by determining the mass-to-charge ratio of peptide fragments, allowing for precise protein identification from excised gel bands. |

| Western Blotting | Uses specific antibodies to detect and confirm the presence of a target protein (e.g., IAM38, CD4) in sperm cell lysates. |

| Specific Blocking Antibodies | Antibodies against candidate proteins (e.g., anti-IAM38, anti-CD4) used to inhibit protein function and assess its role in DNA binding/uptake. |

| DNA Fluorescence Labeling | Tagging exogenous DNA with a fluorescent marker (e.g., for EGFP) to track its uptake and expression in embryos. |

Methodology:

- Sperm Preparation:

DNA-Protein Binding Assay:

- Incubate the washed sperm with a defined fragment of exogenous DNA during the capacitation period.

- Lyse the sperm cells to release intracellular contents, including any DNA-protein complexes.

Separation and Identification:

- Load the lysate onto a native polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis. This preserves the interaction between proteins and DNA.

- After electrophoresis, stain the gel with Coomassie Blue. A distinct band that appears in the DNA-treated sample but not in the control may represent a DNA-protein complex.

- Excise the band of interest and subject it to mass spectrometry analysis for protein identification.

Confirmation and Functional Analysis:

- Confirm the presence of identified proteins (e.g., IAM38, CD4) in sperm, but not seminal plasma, using Western blotting [9].

- For functional validation, pre-incubate sperm samples with specific blocking antibodies against the target protein (e.g., anti-IAM38). Then, perform the DNA-binding and uptake assay to quantify the reduction in efficiency.

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps for identifying and validating DNA-binding proteins.

Protocol: Standard Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer

This protocol describes the general workflow for generating transgenic animals via SMGT, as applied in species like mice and pigs [1] [3] [10].

Objective: To produce transgenic offspring by fertilizing oocytes with sperm that have incorporated exogenous DNA.

Methodology:

- Sperm Preparation and DNA Incubation:

- Collect and wash sperm extensively to remove seminal plasma.

- Incubate the capacitated sperm cells with the plasmid DNA containing the transgene of interest for a defined period (e.g., 30-60 minutes).

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF):

- Add the DNA-treated sperm suspension to freshly ovulated oocytes in culture.

- Allow fertilization to proceed under standard IVF conditions.

Embryo Transfer and Analysis:

- Culture the fertilized oocytes until they reach the desired cleavage stage.

- Transfer the cleaved embryos into the oviducts of synchronized pseudopregnant recipient females [10].

- Bring the pregnancies to term and analyze the resulting offspring for the presence and expression of the transgene using PCR, Southern blotting, and fluorescence observation (if a reporter gene like EGFP is used).

The molecular mechanism of SMGT is a sophisticated process mediated by specific DNA-binding proteins, such as IAM38 and CD4, which facilitate the binding, internalization, and nuclear transport of exogenous DNA. While natural barriers like seminal plasma factors and endogenous nucleases pose challenges, standardized protocols that include extensive sperm washing and optimized fertilization conditions can significantly improve efficiency. The emerging understanding of SMGT as a retrotransposon-mediated process opens new avenues for research. Future work should focus on further elucidating the structure and function of DBPs, standardizing protocols to achieve consistent high efficiency across species, and carefully exploring the potential of this technology for gene therapy and the generation of advanced biomedical models.

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) represents a promising transgenic technique that utilizes the innate ability of sperm cells to bind, internalize, and transport exogenous DNA into an oocyte during fertilization to produce genetically modified animals [1]. Despite its theoretical simplicity and potential applications in biomedical, agricultural, and veterinary research, SMGT has faced significant challenges in achieving consistent experimental outcomes and establishing itself as a reliable genetic manipulation method [1] [11]. The primary reason for this inconsistency lies in the sophisticated natural barriers that protect sperm cells from unintended genetic alterations, maintaining genomic integrity across generations [1]. These protective mechanisms include seminal plasma inhibitory factors and endogenous nuclease activities that collectively minimize the risk of foreign DNA integration during fertilization [1]. Understanding and overcoming these barriers is fundamental to advancing SMGT from an experimental curiosity to a robust biotechnology platform.

This application note provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers aiming to optimize SMGT protocols by addressing these natural barriers. We present detailed experimental data on nuclease activities across species, systematic analyses of inhibitory mechanisms, and validated methodologies for bypassing these protections. Additionally, we provide visual workflow summaries and essential research reagent solutions to facilitate implementation of effective SMGT strategies in diverse experimental models.

Mechanisms of Natural Barriers

Seminal Plasma Inhibitory Factors

Seminal plasma contains specific factors that actively prevent the interaction between spermatozoa and exogenous DNA molecules. The primary mechanism involves DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) present on the surface of sperm cells that lose their DNA-binding capability when exposed to seminal plasma components [1]. This inhibitory effect is rapidly established post-ejaculation, as demonstrated by studies showing increased sperm nuclear resistance to chromatin decondensation within minutes after ejaculation, a stabilization process significantly reduced by saline dilution of semen [12]. The inhibitory factor effectively creates a molecular shield that blocks the binding of foreign genetic material to sperm cells, thereby preventing potential mutagenic events during fertilization [1].

Endogenous Nuclease Activities

Multiple nuclease activities have been identified in seminal plasma across species, representing a second major barrier to SMGT. These nucleases rapidly degrade exogenous DNA before it can interact with sperm cells [13] [11]. Research has confirmed the presence of robust nuclease cocktails in rooster seminal plasma that efficiently degrade plasmid DNA within hours [11]. Similarly, human seminal plasma demonstrates significant DNase I and II activities that induce single-stranded DNA breaks in sperm cells and somatic cells [13]. These nucleases function as an enzymatic defense system, destroying foreign genetic material that might otherwise be incorporated during fertilization.

Table 1: Seminal Plasma Nuclease Activities Across Species

| Species | Nuclease Types Identified | Degradation Efficiency | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | DNase I, DNase II | High (induces single-strand breaks) | Active in seminal plasma; inhibited by HFF chelators [13] |

| Rooster | Robust nuclease cocktail | Degrades 2μg plasmid in 1h | Bypassed by lipoplex structures [11] |

| Mammals | Multiple nucleases | Variable between species | Includes endogenous sperm nuclease activity [1] |

Quantitative Analysis of Barrier Systems

Experimental Measurements of Nuclease Activity

Systematic evaluation of nuclease activity in reproductive fluids provides critical data for developing effective SMGT strategies. Quantitative assessments demonstrate that incubation of genomic DNA with human seminal plasma induces significant degradation, while human follicular fluid (HFF) shows no detectable nuclease activity under identical conditions [13]. The degradation kinetics follow a time-dependent pattern, with substantial DNA fragmentation occurring within 30-60 minutes of exposure to seminal plasma. Importantly, HFF contains chelating agents that inhibit both its own latent nuclease activity and seminal plasma nucleases, potentially through metal ion chelation essential for nuclease function [13]. This protective effect of HFF is concentration-dependent, with higher HFF concentrations providing more complete protection against DNA degradation.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Nuclease Activity and Inhibition

| Parameter | Seminal Plasma | Human Follicular Fluid (HFF) | HFF + Seminal Plasma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Activity | High (degrades genomic DNA) | None detected | Significant inhibition |

| Key Components | DNase I, DNase II | Latent nuclease + chelators | Chelators dominate |

| Inhibition Mechanism | N/A | Metal ion chelation | Metal ion chelation |

| Effect on DNA Integrity | Fragmentation | Protection | Protected with sufficient HFF |

| Functional Consequence | Barrier to SMGT | Protective for sperm DNA | Synergistic protection |

Species-Specific Variations

Comparative analyses reveal significant interspecies variation in seminal plasma nuclease activity and sensitivity to inhibition. Rooster seminal plasma demonstrates particularly robust nuclease activity that requires specific lipoplex formulations for effective protection [11]. In contrast, bovine and equine seminal plasma show intermediate nuclease levels that can be modulated through extenders and processing techniques [13]. These variations necessitate species-specific optimization of SMGT protocols, particularly in the choice of protective agents and incubation conditions.

Protocols for Overcoming Natural Barriers

Seminal Plasma Removal and Sperm Washing

Principle: Physical separation of spermatozoa from seminal plasma eliminates both the inhibitory factors that block DNA-binding protein function and the nucleases that degrade exogenous DNA [1].

Protocol:

- Collect fresh semen samples in sterile containers

- Dilute samples 1:3 with pre-warmed (37°C) PBS or physiological saline

- Centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature

- Carefully aspirate supernatant without disturbing sperm pellet

- Resuspend pellet in equal volume of washing medium

- Repeat centrifugation and washing steps twice

- Confirm sperm viability and motility post-washing

- Proceed immediately to DNA incubation steps

Technical Notes: Excessive washing may reduce sperm viability; optimize cycle number for each species. Maintain samples at physiological temperature throughout process. Include viability controls with each experiment [1] [11].

DNA Protection via Lipoplex Formation

Principle: Complexing DNA with lipofection reagents creates protected nanoparticles resistant to nuclease degradation while facilitating cellular uptake [11].

Protocol:

- Dilute purified plasmid DNA (≥1μg/μL) in nuclease-free water or Tris-EDTA buffer

- Prepare TransIT or alternative lipofection reagent at room temperature

- Combine DNA and transfection reagent at optimal ratios (1:1 to 1:3 μg:μL)

- Mix gently by pipetting, do not vortex

- Incubate mixture at 25°C for 60 minutes to form stable lipoplexes

- Confirm complex formation by gel retardation assay

- Use lipoplexes immediately for sperm incubation

Technical Notes: Optimal DNA:reagent ratios vary by transfection reagent and species; require empirical determination. Lipoplex stability varies with temperature and buffer conditions; avoid freeze-thaw cycles [11].

Inhibition of Nuclease Activity

Principle: Chelating agents in human follicular fluid and chemical inhibitors block metal-dependent nuclease activity, preserving DNA integrity [13].

Protocol:

- Prepare seminal plasma by centrifugation at 19,000 × g for 10 minutes

- Collect supernatant and filter-sterilize (0.22μm)

- Add HFF (50-80% v/v) or EDTA (1-5mM) to seminal plasma

- Pre-incubate inhibitor-seminal plasma mixture for 15 minutes at 37°C

- Add DNA or DNA lipoplexes to inhibited seminal plasma

- Incubate for desired duration at physiological temperature

- Assess DNA integrity by gel electrophoresis or quantitative assays

Technical Notes: HFF sourcing requires ethical approval and appropriate consent. EDTA concentration must be optimized to balance nuclease inhibition with sperm viability [13].

Experimental Workflow for SMGT Optimization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SMGT Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm Washing Media | PBS, Physiological Saline, Specialized extenders | Removes seminal plasma and inhibitory factors | Must maintain sperm viability; species-specific formulations may be required [1] |

| Transfection Reagents | TransIT (Mirus), Lipofectamine, other lipoplex formers | Protects DNA from nucleases and enhances cellular uptake | Optimal DNA:reagent ratio must be determined empirically for each system [11] |

| Nuclease Inhibitors | Human Follicular Fluid (HFF), EDTA, EGTA | Chelates metal ions required for nuclease activity | HFF requires ethical sourcing; chemical inhibitors may affect sperm function [13] |

| Proteomic Analysis Tools | TMT labeling, LC-MS/MS, Label-free quantification | Identifies protein changes in seminal plasma post-intervention | Requires specialized equipment and expertise; provides comprehensive protein profiling [14] [15] |

| DNA Integrity Assays | Gel electrophoresis, PCR, Fluorometric assays | Quantifies DNA degradation and protection efficiency | Should be performed at multiple timepoints to assess degradation kinetics [11] |

Applications and Future Perspectives

The methodologies described herein for overcoming natural barriers in SMGT have far-reaching implications across multiple research domains. In animal transgenesis, optimized SMGT protocols enable production of genetically modified models for biomedical research with potential efficiencies as high as 80% in some experimental systems [1]. For agricultural biotechnology, SMGT offers a simplified approach for generating transgenic livestock with improved production traits or disease resistance. The most significant future application may emerge in gene therapy, where the inverse correlation between patient age and treatment effectiveness makes embryonic intervention particularly attractive [1]. The discovery that sperm cells possess endogenous retrotransposon-encoded reverse transcriptase activity that can reverse transcribe exogenous RNA into cDNA copies further expands SMGT's potential [4]. This mechanism suggests SMGT represents a retrotransposon-mediated phenomenon that could be harnessed for more sophisticated genetic engineering strategies.

Current research continues to refine our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying sperm-DNA interaction and the protective barriers that regulate this process. Future directions include identifying specific inhibitory factors in seminal plasma, characterizing nuclease isoforms across species, and developing novel nanoparticle formulations that provide enhanced DNA protection while maintaining sperm functionality. Integration of SMGT with emerging gene editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 systems represents particularly promising avenue for future innovation. As these methodologies mature, SMGT is positioned to transition from specialized laboratory technique to established biotechnology platform with broad applications across research and therapeutic domains.

Nuclear Internalization and Fate of Foreign DNA within the Sperm Cell

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) presents a paradigm-shifting approach in transgenic technology, leveraging the innate capacity of spermatozoa to function as natural vectors for exogenous genetic material [3] [1]. This biological phenomenon, once considered controversial, provides a simplified and cost-effective alternative to conventional transgenesis methods such as pronuclear microinjection, requiring neither complex embryo manipulation nor specialized equipment [3]. The process is fundamentally governed by the sperm cell's spontaneous ability to bind, internalize, and transport foreign DNA into the oocyte during fertilization, ultimately leading to the generation of genetically modified offspring [16] [1].

The core premise of SMGT rests upon a series of highly regulated molecular interactions between mature sperm cells and exogenous DNA sequences. Contrary to initial assumptions of a passive or random association, research confirms that this interaction constitutes a specific, regulated process mediated by distinct sperm surface factors and intracellular mechanisms [16] [4]. This application note delineates the precise mechanisms governing nuclear internalization and the subsequent fate of foreign DNA within sperm cells, providing researchers with detailed protocols and analytical frameworks to advance applications in animal transgenesis, gene therapy, and basic reproductive science.

Mechanisms of Sperm-DNA Interaction and Internalization

The journey of foreign DNA from the extracellular environment into the sperm nucleus involves a coordinated sequence of binding, internalization, and potential integration events, each mediated by specific molecular players.

Initial Binding and Surface Interactions

The initial contact between sperm cells and foreign DNA is not a stochastic event but is facilitated by specific DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) present on the sperm head's plasma membrane [16] [1]. These DBPs possess a high affinity for exogenous DNA molecules, enabling stable complex formation. A critical regulatory aspect of this stage is the presence of an inhibitory factor in the seminal fluid that naturally antagonizes this binding interaction [16] [1]. Consequently, successful experimental protocols for SMGT necessitate the thorough removal of seminal plasma through extensive washing procedures post-ejaculation to liberate DBPs from inhibition and permit DNA binding [1].

Table 1: Key Molecular Mediators of Sperm-DNA Interaction

| Molecule/Factor | Localization | Function in SMGT | Effect of Inhibition/Block |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Proteins (DBPs) | Sperm cell surface (head) | Mediate specific binding of exogenous DNA molecules | Prevents initial association of DNA with sperm cells [16] |

| Seminal Fluid Inhibitory Factor | Seminal plasma | Antagonizes DBP activity, blocks foreign DNA binding | Removal is essential for successful SMGT [1] |

| CD4 Molecule | Sperm cell surface | Mediates the internalization of bound DNA into the sperm nucleus [16] | Significant reduction in DNA internalization; disrupts transport pathway [16] [17] |

| Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II (MHCII) | Sperm cell surface | Participates in the initial DNA binding step [17] | Disconnection from CD4 more impactful than block alone [17] |

Nuclear Internalization and Triggered Metabolic Functions

Following surface binding, a portion of the foreign DNA is internalized into the sperm nucleus. This critical step is mediated by CD4 molecules, the same surface receptors involved in immune cell signaling [16]. The internalization of foreign DNA is not a metabolically inert process; instead, it actively triggers otherwise repressed enzymatic functions within the mature spermatozoon [16] [4]. Key among these is the activation of endogenous nuclease activity that cleaves both the exogenous and the sperm's own genomic DNA, initiating a cell death process resembling apoptosis [16] [17]. This nuclease activity likely functions as a natural barrier against the intrusion of foreign genetic material [1]. Furthermore, spermatozoa possess an endogenous retrotransposon-encoded reverse transcriptase activity, capable of reverse-transcribing exogenous RNA molecules into cDNA copies that can subsequently be delivered to the embryo during fertilization [4].

Figure 1: Signaling Pathway of Foreign DNA Internalization and Fate in Sperm Cells. The diagram illustrates the sequential steps from initial DNA binding, internalization mediated by surface receptors, to the triggered intracellular responses and potential outcomes leading to oocyte fertilization.

Quantitative Dynamics of Sperm-DNA Interaction

The efficiency of foreign DNA internalization is governed by a dynamic equilibrium between competing biochemical reactions. Computational modeling using ordinary differential equations (ODE) has delineated the kinetic parameters of this system, simulating the flow of DNA between different states—from free molecules to internalized cargo [17].

The model accounts for key variables, including free foreign DNA, complexes with MHCII and CD4 proteins, compartmentalization within the sperm cell, and degradation by DNases both outside and inside the spermatozoon [17]. Simulations reveal that the process involves distinct phases: a delay phase, a period of active DNA internalization, a plateau, and finally a decrease in internal DNA content due to the action of endogenous nucleases [17]. Importantly, modeling indicates that DNases in seminal fluid do not completely prevent foreign DNA penetration, and the MHCII-CD4 interaction is a critical node in the internalization pathway [17]. Artificial disconnection of MHCII and CD4 proteins has a more detrimental effect on DNA uptake than simply blocking MHCII alone [17].

Table 2: Key Parameters from ODE Modeling of Sperm-DNA Interaction [17]

| Parameter/Variable | Description | Simulated Impact / Value |

|---|---|---|

| S1 (Free DNA) | Concentration of exogenous DNA available for binding | Initial condition set to 1 (input) |

| S2 (MHCII-bound DNA) | DNA complexed with Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II | Rapid binding phase (k1 = 1, strong chemical affinity) |

| S3 (CD4-bound DNA) | DNA complexed with CD4 receptor | Intermediate state before internalization |

| S4 (Internalized DNA) | Foreign DNA successfully internalized into sperm cell | Shows delay, internalization, plateau, and decrease phases |

| S5, S6 (Cleaved DNA) | DNA degraded by DNases outside (S5) and inside (S6) sperm | k5 = {0, 1}, k6 = {0, 0.1, 1} |

| k1 (MHCII binding rate) | Rate constant for DNA binding to MHCII | High value (1) simulates fast, strong binding |

| k2, k12, k3 (Complex transport) | Rate constants for interactions between MHCII, CD4, and internalization | Varied in 'genetic' experiments (0, 0.1) |

| Key Finding: MHCII-CD4 Link | Disconnection of MHCII and CD4 (k2=0) | More significant reduction in DNA internalization than MHCII block alone |

Sperm Chromatin Architecture and the Fate of Internalized DNA

The ultimate fate of internalized foreign DNA is profoundly influenced by the unique, highly condensed architecture of sperm chromatin. Mammalian sperm chromatin is organized into three primary structural domains, each with distinct functional implications for the processing and integration of exogenous genetic material [18].

Protamine-bound Chromatin (~85-98%): The vast majority of sperm DNA is packaged into toroidal structures by protamines, which neutralize the DNA backbone and form intermolecular disulfide cross-links for stability [18]. This configuration renders the DNA highly resistant to mechanical disruption and nuclease digestion, primarily serving a protective function during fertilization rather than a regulatory one in the embryo, as protamines are replaced by histones in the oocyte shortly after fertilization [18].

Histone-bound Chromatin (2-15%): A small but critical fraction of sperm DNA remains bound to histones. This association is non-random and is preferentially located at gene promoters and genomic regions crucial for early embryonic development, such as developmental transcription factors and signaling genes [18]. This histone-bound chromatin is thought to carry epigenetic information that is transferred to the paternal pronucleus post-fertilization.

Nuclear Matrix Attachment Regions (MARs): The sperm DNA is anchored to the nuclear matrix at approximately 50 kb intervals. These MARs are also transferred to the paternal pronucleus and are essential for the initiation of DNA replication in the developing embryo [18].

Internalized foreign DNA that escapes degradation reaches the nuclear matrix and can undergo recombination with chromosomal DNA [16]. The specific integration site may be influenced by this chromatin landscape, potentially favoring more accessible histone-bound regions or matrix attachment sites.

Experimental Protocol for Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for conducting SMGT, optimized for generating transgenic models, and can be adapted for various species.

Reagent Preparation

- Sperm Washing Buffer: A calcium-free medium, such as a modified Tyrode's or Hepes-buffered saline, supplemented with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.4-1.0%) to prevent premature capacitation and maintain sperm viability.

- DNA Vector Solution: Purified plasmid DNA containing the transgene of interest, dissolved in TE buffer or nuclease-free water at a concentration of 1-10 µg/µL. The DNA should be of high purity (e.g., endotoxin-free, column-purified).

- Capacitation Medium: A defined medium containing bicarbonate, BSA, and sometimes calcium, specific to the species under investigation, to support the physiological process of sperm capacitation.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sperm Collection and Washing:

- Collect semen via ejaculation or from the cauda epididymis.

- Critically, dilute the semen sample 1:3 to 1:5 in pre-warmed Sperm Washing Buffer.

- Centrifuge at 500 x g for 10 minutes to pellet sperm cells.

- Carefully aspirate and discard the supernatant, which contains the inhibitory factors present in the seminal fluid [1].

- Repeat the washing step a total of two to three times to ensure complete removal of seminal plasma.

Sperm Capacitation and DNA Incubation:

- Resuspend the final sperm pellet in Capacitation Medium.

- Adjust the sperm concentration to 1-5 x 10^6 sperm/mL.

- Add the DNA Vector Solution directly to the sperm suspension to a final concentration of 10-100 ng/µL.

- Incubate the sperm-DNA mixture for 30-120 minutes at the appropriate temperature and CO₂ conditions for the species (e.g., 37°C, 5% CO₂ for mice) to allow for simultaneous capacitation and DNA binding/internalization.

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) and Embryo Transfer:

- Use the transfected sperm suspension to fertilize freshly ovulated, metaphase II oocytes using standard IVF techniques for the species.

- The following day, assess the oocytes for successful fertilization (presence of two pronuclei).

- Transfer the resulting cleaved embryos (at the 2-cell stage for mice) into the oviducts of pseudopregnant recipient females for gestation [10].

Figure 2: SMGT Experimental Workflow. The diagram outlines the key steps from sperm preparation and DNA incubation to fertilization and analysis of resulting offspring.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SMGT

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SMGT Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Plasmid DNA | Source of the transgene for uptake and integration. | High purity (endotoxin-free) is critical. Size and topology can influence efficiency [1]. |

| Sperm Washing Buffer (Ca²âº-free) | Removal of seminal plasma inhibitory factors. | Must be isotonic and contain energy substrates (e.g., pyruvate, lactate) and BSA to maintain viability [1]. |

| Capacitation Medium | Supports physiological changes enabling sperm to fertilize and interact with DNA. | Species-specific; typically requires bicarbonate, BSA, and calcium to induce capacitation. |

| DNase I (Experimental Control) | To confirm internalization is specific and not due to surface adherence. | Treatment of DNA-incubated sperm with DNase I degrades non-internalized DNA [17]. |

| IF-1 (Inhibitory Factor-1) | Experimental tool to study binding blockade. | Mimics the action of the seminal fluid inhibitor. Modeling shows it significantly reduces internalization, especially with active DNase [17]. |

| Antibodies vs CD4/MHCII | Molecular tools to block specific interaction steps. | Used to validate the roles of these receptors in the internalization pathway [16] [17]. |

| Fmoc-L-Orn(Mmt)-OH | Fmoc-L-Orn(Mmt)-OH, MF:C40H38N2O5, MW:626.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Bromo-1,1-dichlorobutane | 4-Bromo-1,1-dichlorobutane, CAS:144873-00-7, MF:C4H7BrCl2, MW:205.91 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Critical Considerations and Troubleshooting

- Variable Efficiency: The success rate of SMGT can be highly variable, with some experiments yielding over 85% transgenic offspring while others fail entirely [10]. This underscores the influence of subtle, often undefined factors in the protocol.

- Barrier Activation: Researchers must be mindful that the internalization of foreign DNA can trigger apoptotic-like pathways, including endogenous nucleases, which may reduce the population of viable, transfected spermatozoa [16]. Optimizing DNA concentration and exposure time is essential to balance uptake with cell survival.

- Validation of Integration: The integration mechanism of foreign DNA post-fertilization remains an active area of research. Proposed mechanisms include integration during oocyte activation, paternal pronucleus decondensation, or pronuclei formation [1]. Analysis of founder animals (F0) and subsequent Mendelian inheritance in the F1 generation is necessary to confirm stable genomic integration.

The Role of Endogenous Retrotransposons in Reverse Transcription and Gene Propagation

Endogenous retrotransposons are mobile genetic elements that constitute a substantial portion of eukaryotic genomes, utilizing reverse transcription to amplify their sequences and propagate within host DNA. These elements are broadly categorized into two main classes: Long Terminal Repeat (LTR) retrotransposons, which include endogenous retroviruses, and non-LTR retrotransposons, primarily consisting of Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements (LINEs) and Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements (SINEs) [19]. Through their replicative activities, retrotransposons have become major drivers of genome evolution and diversity, accounting for approximately 45% of the human genome [20] and similarly significant proportions in other species.

The connection between retrotransposition and germline transmission is particularly relevant in the context of sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT), a technique that utilizes sperm cells as natural vectors for introducing foreign genetic material into oocytes during fertilization [21] [22]. Understanding how endogenous retroelements utilize reverse transcription and integration mechanisms provides valuable insights for optimizing SMGT protocols and applications in transgenic animal production. This application note explores the mechanisms of retrotransposon replication and their practical implications for biotechnology.

Molecular Mechanisms of Retrotransposition

Structural Features of Retroelements

Autonomous retrotransposons encode the necessary proteins for their own mobilization. The human LINE-1 (L1) element, the most abundant autonomous non-LTR retrotransposon, exemplifies this structure with two open reading frames: ORF1 encodes an RNA-binding protein with nucleic acid chaperone activity, while ORF2 encodes a protein with both reverse transcriptase (RT) and endonuclease (EN) activities [20]. Full-length L1 elements are approximately 6 kb long and are flanked by target site duplications, with a characteristic polyadenylate tail at their 3' end [19].

LTR retrotransposons and endogenous retroviruses exhibit a different organization, containing gag, pro, pol, and sometimes env genes flanked by long terminal repeats that regulate their expression [23] [19]. The pol gene encodes reverse transcriptase and integrase enzymes essential for their replication cycle. Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) account for approximately 8% of the human genome and, while most are inactive, some retain protein-coding capacity and regulatory functions [23].

Replication Cycle of Non-LTR Retrotransposons

The replication mechanism of non-LTR retrotransposons, particularly LINE elements, occurs through a process called target-primed reverse transcription (TPRT) [20]. The following steps outline this complex process:

Transcription and Translation: Retrotransposon DNA is transcribed in the nucleus by RNA polymerase II, producing an mRNA that is exported to the cytoplasm. This mRNA is translated to produce ORF1 and ORF2 proteins, which associate with their own encoding mRNA to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particle [20].

Nuclear Import and Target Site Selection: The RNP complex is imported back into the nucleus. The ORF2 endonuclease component then cleaves one strand of genomic DNA at the consensus sequence 5'-TTTT/A-3' or variants thereof [24] [20].

Reverse Transcription and Integration: The newly generated 3' hydroxyl group on the genomic DNA serves as a primer for ORF2 reverse transcriptase to copy the retrotransposon RNA into DNA. Second-strand cleavage and synthesis complete the integration process, creating a new retrotransposon copy flanked by short target site duplications [20].

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the non-LTR retrotransposition mechanism:

Regulatory Control of Retrotransposition

Retrotransposition is tightly regulated in most somatic cells through epigenetic mechanisms, primarily DNA methylation of CpG islands in the L1 5' UTR [25] [24]. The L1 promoter contains a CpG island that is typically methylated in differentiated cells, effectively silencing L1 transcription. Additional repression is mediated by proteins such as Sox2 and MeCP2, which associate with the L1 5' UTR and contribute to transcriptional control [24].

This repression is selectively lifted in certain biological contexts. During early embryonic development, global demethylation permits temporary retrotransposon activation [23]. Notably, L1 retrotransposition occurs in neural progenitor cells, contributing to somatic mosaicism in the brain [24]. Similarly, retrotransposon reactivation is frequently observed in various cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer, where epigenetic dysregulation leads to increased retrotransposition activity [25] [26].

Quantitative Analysis of Retrotransposition Activity

Endogenous Retrotransposon Activity in Human Tissues

Retrotransposition activity varies significantly across tissue types and developmental stages. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings on endogenous retrotransposon activity in human tissues:

Table 1: Quantified Retrotransposition Activity in Human Tissues and Cancers

| Tissue/Condition | Retrotransposon Type | Measurement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average human genome | LINE-1 (L1) | 500,000 copies; 80-100 active | [19] [20] |

| Neural progenitor cells | Engineered L1 | 8-12 events/100,000 cells | [24] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Endogenous L1 | 21.1% with germline insertions in MCC | [25] |

| Human hippocampus | Endogenous L1 | Increased copy number vs. heart/liver | [24] |

| Colorectal epithelial cells | Endogenous L1 | 1,708 somatic events | [19] |

| Human fetal brain | L1 5'UTR | Significantly less methylated vs. skin | [24] |

Cancer-Associated HERV Expression Patterns

Human endogenous retroviruses exhibit distinct expression profiles across cancer types, suggesting potential roles as biomarkers or therapeutic targets:

Table 2: HERV Family Expression in Selected Cancers

| HERV Family | Cancer Types with Documented Expression |

|---|---|

| HERV-E | Clear cell kidney cancer, breast cancer |

| HERV-K | Breast cancer, melanoma, germ cell tumors, leukemia, colon cancer |

| HERV-H | Gastrointestinal/pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, colon cancer, lung cancer |

| HERV-W | Testicular cancer, germ cell tumors, non-small cell lung cancer, endometrial carcinoma |

| HERV-FRD | Seminomas, glioblastoma |

| HEMO | Breast cancer, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer |

Data compiled from [23]

Experimental Protocols for Retrotransposition Analysis

Engineered L1 Retrotransposition Assay

This protocol enables quantitative analysis of L1 retrotransposition efficiency in cultured cells, including neural progenitor cells and other permissive cell types [24]:

Principle: A retrotransposition-competent L1 (RC-L1) vector contains an antisense reporter gene (EGFP) interrupted by an intron in the same transcriptional orientation as the L1. Successful retrotransposition results in EGFP expression.

Reagents and Equipment:

- RC-L1 plasmid (e.g., L1RP)

- Control plasmid with mutated ORF1 (JM111/L1RP)

- Appropriate cell culture system (e.g., hCNS-SCns, hESC-derived NPCs)

- Transfection reagents

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence microscope

- RNA extraction kit

- RT-PCR reagents

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture target cells (e.g., neural progenitor cells) under appropriate conditions.

- Transfection: Introduce 500-5,000 copies of RC-L1 plasmid per cell using preferred transfection method.

- Incubation: Maintain transfected cells for sufficient time to allow retrotransposition events (typically 2-4 weeks).

- Analysis:

- Quantify EGFP-positive cells by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

- Confirm precise splicing of intron from retrotransposed EGFP gene by RT-PCR.

- Verify integration sites by sequencing.

- Controls: Include parallel transfections with ORF1-mutant L1 (JM111) to confirm dependence on L1-encoded proteins.

Expected Results: Typical retrotransposition efficiency in human fetal NPCs averages 8-12 events per 100,000 transfected cells [24]. hESC-derived NPCs generally show higher retrotransposition efficiency.

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer Protocol

This protocol adapts natural sperm DNA uptake for transgenesis, leveraging principles similar to retrotransposon propagation [21] [22] [2]:

Principle: Sperm cells spontaneously bind and internalize exogenous DNA, which can be transferred to oocytes during fertilization to generate transgenic offspring.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Fresh spermatozoa (species-specific)

- Foreign DNA of interest (100-200 ng/µL)

- DNase inhibitors (optional)

- Lipofection reagents (e.g., Lipofectin)

- In vitro fertilization system

- Embryo culture media

Procedure:

- Sperm Preparation: Collect fresh sperm and remove seminal plasma by centrifugation.

- DNA Incubation: Incubate sperm cells with foreign DNA (100-200 ng/µL) for 30-60 minutes at appropriate temperature.

- DNase Treatment (Optional): Treat DNA-bound sperm with DNase to remove uninternalized DNA.

- Fertilization: Use DNA-loaded sperm for in vitro fertilization or artificial insemination.

- Embryo Transfer: Implant fertilized oocytes into synchronized foster females.

- Transgenic Screening: Analyze offspring for transgene integration via PCR, Southern blot, or reporter expression.

Expected Results: Efficiency varies by species but typically ranges from 1-10% transgenic offspring relative to total embryos transferred [22]. The technique has successfully generated transgenic mice, rabbits, pigs, sheep, cattle, chickens, and fish [22].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps in the sperm-mediated gene transfer protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Retrotransposition and SMGT Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| RC-L1 Reporter Plasmids | Quantitative retrotransposition assays | EGFP, neomycin, or blasticidin reporter cassettes in antisense orientation with intron [24] |

| Retroviral Vectors | Gene delivery and integration | Capacity: 7-8 kb foreign DNA; suitable for germline integration [22] |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | High-efficiency gene delivery | Capacity: ~10 kb foreign DNA; minimal pathogenicity [22] |

| Sperm Binding Reagents | Enhance DNA uptake in SMGT | Lipofectin, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), N,N-dimethylacetamide [21] |

| Methylation Analysis Tools | Epigenetic regulation studies | Bisulfite conversion kits; L1 5'UTR specific primers [24] |

| Integration Site Mapping | Genomic localization | Retrotransposon Capture Sequencing (RC-seq); enhanced protocols with multiplex liquid-phase capture [25] |

| Bromide ion Br-77 | Bromide Ion Br-77 | Bromide Ion Br-77 is for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

| 6,6-Dimethylheptan-1-amine | 6,6-Dimethylheptan-1-amine | 6,6-Dimethylheptan-1-amine is a chemical reagent for professional research applications. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human consumption. |

Applications in Biotechnology and Medicine

The mechanistic understanding of endogenous retrotransposition has enabled several biotechnology applications:

Transgenic Animal Production

Sperm-mediated gene transfer leverages the natural ability of sperm to bind and internalize exogenous DNA, providing a efficient method for transgenic animal production [21] [22]. Compared to pronuclear microinjection, SMGT offers advantages of technical simplicity, lower equipment requirements, and potential for mass transgenesis. Success rates vary by species, with reported efficiencies of 1-10% transgenic offspring relative to total embryos transferred [22].

The exploration of endogenous retrotransposon mechanisms has revealed that sperm cells may possess inherent reverse transcriptase activity derived from endogenous retroelements, which could facilitate foreign DNA integration during SMGT procedures [21]. This connection underscores the relevance of retrotransposon biology to germline genetic modification technologies.

Gene Therapy Vectors

Retroviral vectors derived from retrotransposons and retroviruses enable stable genomic integration of therapeutic genes [22]. The reverse transcription and integration machinery of these elements has been harnessed for durable gene correction in target cells. Current engineering efforts focus on improving vector safety, including self-inactivating designs and tissue-specific targeting systems.

Cancer Biomarker Development

The reactivation of specific HERV families in cancer tissues provides potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [23] [25]. For example, HERV-K expression is elevated in melanoma, breast cancer, and germ cell tumors, while HERV-E expression characterizes clear cell kidney cancer. Detection of tumor-specific retrotransposition events in circulating DNA could enable non-invasive cancer monitoring.

Endogenous retrotransposons represent powerful natural genetic engineering systems that have profoundly shaped genome evolution. Their sophisticated reverse transcription and integration mechanisms provide valuable tools for biotechnology applications, particularly in the realm of germline genetic modification through techniques like sperm-mediated gene transfer.

Future research directions include refining RC-seq methodologies for comprehensive retrotransposon insertion profiling, developing more specific retrotransposition assays for different tissue contexts, and optimizing SMGT protocols through better understanding of sperm-DNA interaction mechanisms. The continued exploration of retrotransposon biology promises to yield new insights into genome dynamics and enhanced capabilities for genetic manipulation across diverse applications from basic research to therapeutic development.

SMGT in Practice: Protocols and Transformative Biomedical Applications

Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) is a biotechnological method that utilizes sperm cells as natural vectors to deliver foreign genetic material into an oocyte during fertilization [21]. This technique facilitates the introduction of new genes into an organism's genome, serving as a powerful tool in genetic engineering and reproductive biology to enhance genetic diversity and modify traits in various species [21]. For researchers and drug development professionals, SMGT offers a compelling alternative to traditional pronuclear injection due to its high efficiency, relatively low cost, and ease of use, as it does not require direct embryo handling or expensive micromanipulation equipment [27] [28]. A significant implication of SMGT research is the understanding that the process is not casual but a regulated mechanism potentially mediated by endogenous retrotransposons, challenging the traditional view of sperm as metabolically inert cells [4].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and reagents required for the successful execution of the SMGT protocol.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application in SMGT Protocol |

|---|---|

| Semen Extender (e.g., Swine Fertilisation Medium - SFM) | Preserves sperm quality and viability during storage and processing post-collection [28]. |

| Exogenous DNA Construct (e.g., pEGFP-N1) | The foreign genetic material to be transferred into the oocyte; typically linearized [21]. |

| Lipofection Reagent | A cationic liposome-based transfection agent used to enhance the uptake of exogenous DNA by spermatozoa [21]. |

| Sperm Washing Medium | A buffered solution, often containing antibiotics, used to separate motile sperm from seminal plasma and debris [28]. |

| In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) Medium | A defined culture medium that supports the capacitation of sperm and the fertilization of oocytes [28]. |

Experimental Protocol

Sperm Washing and Preparation

- Semen Collection and Initial Evaluation: Collect semen from a donor boar (or other species) and evaluate immediately for standard quality parameters (color, volume, concentration, and motility) [21].

- Washing and Selection of Motile Sperm: Dilute the semen in a pre-warmed sperm washing medium. Centrifuge the mixture to pellet the sperm cells. Carefully remove the supernatant containing seminal plasma. Repeat this washing step if necessary [28]. This process is critical for removing seminal plasma components that may inhibit DNA uptake [28].

- Resuspension: After the final wash, resuspend the sperm pellet in a suitable semen extender or a specific medium like Swine Fertilisation Medium (SFM) to the desired concentration for the DNA uptake step [28].

Sperm Treatment and DNA Uptake

- DNA Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the exogenous DNA construct (e.g., a linearized plasmid such as pVIVO2-GFP/LacZ) at a defined concentration. The standard concentration used is 5 µg/mL, though studies have tested much higher amounts (100 µg/mL) without significantly compromising sperm quality [27] [28].

- Co-incubation with DNA: Incubate the washed, motile spermatozoa with the prepared DNA solution. To enhance transfection efficiency, a lipofection reagent can be added to the mixture [21]. The incubation should be carried out for a defined period, typically at 37°C.

- Post-Incubation Assessment: Following co-incubation, assess the sperm cells again for quality parameters, including motility, membrane integrity, and mitochondrial activity, to ensure the treatment has not adversely affected their fertilizing capability [27] [28].

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) with Transfected Sperm

- Oocyte Collection and Maturation: Collect oocytes from superovulated prepubertal gilts or other donors. Allow the oocytes to mature in vitro to the Metaphase II (MII) stage [28].

- Fertilization: Co-incubate the matured oocytes with the spermatozoa that have been treated with the exogenous DNA. This is typically performed in a specialized IVF medium that supports capacitation and fertilization [28].

- Assessment of Fertilization Success: Approximately 24 hours post-insemination, evaluate the oocytes for successful fertilization by checking for the formation of two pronuclei (zygotes) and subsequent cleavage rates [27] [28].

Figure 1: A flowchart illustrating the step-by-step workflow of the standard SMGT protocol.

Key Data and Results

The success of the SMGT protocol is evaluated through key performance metrics, including sperm quality post-treatment and subsequent embryo development rates. The following tables summarize typical quantitative outcomes from an optimized SMGT experiment in swine.

Table 1: Sperm Quality Parameters Post-DNA Uptake

| Treatment Condition | Motility (%) | Membrane Integrity (%) | Developmental Rate to Blastocyst (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control Sperm | Data not in search results | Data not in search results | 48 |

| SMGT-Treated Sperm (5 µg/mL DNA) | Data not in search results | Data not in search results | 41 |

| SMGT-Treated Sperm (100 µg/mL DNA) | Not significantly affected [27] | Not significantly affected [27] | Data not in search results |

Table 2: In Vitro Fertilization Outcomes with SMGT-Treated Sperm

| Parameter | Control Group | SMGT-Treated Group |

|---|---|---|

| Cleavage Rate (%) | 58 | 60 |

| Transformation Efficiency (%) | — | 62 |

Mechanism Underlying SMGT

The mechanism of SMGT extends beyond the passive binding of DNA to the sperm cell surface. Research indicates it is an active process mediated by specific factors within the sperm [4]. The binding of exogenous DNA triggers enzymatic functions that are otherwise repressed, including an endogenous retrotransposon-encoded reverse transcriptase activity [4]. This activity can reverse transcribe exogenous RNA molecules into cDNA copies. These reverse-transcribed molecules can be propagated in tissues as low-copy, extrachromosomal structures that are mosaic distributed but transcriptionally competent [4]. This suggests that the sperm's endogenous retrotransposon machinery can be a novel source of genetic information and is central to the SMGT phenomenon.

Figure 2: A diagram of the proposed molecular mechanism of SMGT involving reverse transcription.

The field of genetic engineering and gene therapy is critically dependent on advanced delivery vehicles to transport genetic material into target cells. These vectors overcome significant biological barriers that otherwise prevent exogenous nucleic acids from reaching their intracellular targets. Non-viral vectors, particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), have emerged as a safer and more versatile alternative to viral carriers, though they have historically faced challenges with transfection efficacy compared to viral systems [29]. LNPs demonstrate remarkable capability to condense and deliver various nucleic acid molecules ranging from small RNA sequences to large DNA constructs [29]. Simultaneously, sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) represents a unique biological approach that leverages the natural ability of sperm cells to bind, internalize, and transport exogenous DNA during fertilization [3] [1]. This application note examines these advanced delivery systems within the context of sperm-mediated gene transfer research, providing technical protocols and comparative analyses for researchers and drug development professionals.

The fundamental challenge in gene delivery involves navigating both extracellular and intracellular barriers. From the moment of injection, genetic material encounters enzymatic degradation by nucleases, clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES), and physical barriers to cellular uptake due to the anionic nature of both nucleic acids and cell membranes [29]. Success in gene therapy depends largely on developing vehicles that can efficiently bypass these barriers to deliver genetic material to target cells with sufficient expression levels and minimal toxicity [29]. This document outlines the key methodologies, applications, and technical considerations for implementing these delivery systems in research settings focused on sperm-mediated gene transfer techniques.

Principles of SMGT

Sperm-mediated gene transfer (SMGT) is a transgenic technique based on the intrinsic ability of sperm cells to spontaneously bind to and internalize exogenous DNA and transport it into an oocyte during fertilization [1]. First described in 1989, SMGT provides a method for producing genetically modified animals with several distinct advantages [2]. The technique benefits from high efficiency, low cost, and ease of use compared to other transgenic methods, and does not require specialized equipment or extensive embryo manipulation [3]. This makes it particularly valuable for generating large animal models for medical research, agricultural applications, and xenotransplantation studies [3].

The mechanism of SMGT is not a random event but rather a regulated process mediated by specific factors. Exogenous DNA molecules interact with DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) present on the surface of sperm cells, facilitating binding and internalization [1]. However, natural barriers exist against this process, including an inhibitory factor present in mammalian seminal fluid that blocks the binding of sperm cells to exogenous DNA [1]. For successful SMGT, this seminal fluid must be removed through extensive washing immediately after ejaculation to enable DBPs to interact with DNA molecules [1]. Following internalization, the exogenous DNA must integrate into the genome, potentially occurring during oocyte activation, nucleus decondensation, or pronuclei formation [1].

Key Enhancements and Technical Variations

Recent research has focused on improving the efficiency of SMGT through various technical enhancements. A 2024 systematic review compared sperm-mediated and testis-mediated gene transfer (TMGT) methods, highlighting optimal approaches for different species [30]. For the SMGT approach in mice, nanoparticles, streptolysin-O, and virus packaging were identified as the most effective gene transfer methods [30]. The efficiency of producing transgenic animals varies significantly depending on species, gene carrier, and transfer method, necessitating careful experimental design.

Table 1: Comparison of Sperm-Mediated and Testis-Mediated Gene Transfer Methods

| Aspect | Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer (SMGT) | Testis-Mediated Gene Transfer (TMGT) |

|---|---|---|

| Most Common Species | Mice and rats | Mice and rats |

| Optimal Gene Transfer Methods | Nanoparticles, streptolysin-O, virus packaging | Virus packaging, DMSO, electroporation, liposome |

| Number of Studies (2010-2022) | 47 | 25 |

| Key Advantages | Does not require embryo handling; relatively simple procedure | Direct targeting of testicular tissue |

| Notable Applications | Production of multigene transgenic pigs for xenotransplantation | Transfection of spermatogonial stem cells |

Beyond standard SMGT protocols, several variations have been developed to enhance efficiency. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)-mediated gene transfer involves injecting sperm that has been incubated with DNA directly into oocytes, showing improved transgenesis rates in some species [2]. Additional methods include electroporation of sperm in the presence of exogenous DNA and treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or N,N-dimethylacetamide to facilitate DNA uptake, particularly in avian species [2]. These technical refinements have progressively addressed the primary limitation of SMGT – the relatively low and variable efficiency of transgene transmission – making it an increasingly reliable method for transgenic animal production.

Lipid-Based Delivery Systems

Composition and Mechanism of Action

Lipid nanoparticles represent one of the most advanced non-viral vector platforms for gene delivery. These systems typically consist of cationic lipids that electrostatically bind to nucleic acids, helper lipids that enhance stability and fusogenicity, and PEGylated lipids that provide a steric barrier to prevent aggregation and reduce immune recognition [29]. The fundamental mechanism involves condensing genetic material into nanoparticles that protect it from degradation and facilitate cellular uptake through endocytosis. Following internalization, LNPs enable endosomal escape through phase transitions that disrupt endosomal membranes, releasing genetic material into the cytoplasm [29].