Unraveling Familial Endometriosis: The Critical Role of Rare Genetic Variants in Disease Aggregation and Pathogenesis

This article synthesizes current research on the role of rare genetic variants in familial endometriosis aggregation, a area complementing common variant studies from GWAS.

Unraveling Familial Endometriosis: The Critical Role of Rare Genetic Variants in Disease Aggregation and Pathogenesis

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the role of rare genetic variants in familial endometriosis aggregation, a area complementing common variant studies from GWAS. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the polygenic architecture of familial disease, details advanced methodologies like Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and family-based study designs for variant discovery, and discusses bioinformatic strategies for prioritizing pathogenic candidates. The content further covers the functional validation of rare variants and their integration with multi-omics data, concluding with a perspective on translating these genetic insights into novel diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapeutic strategies.

The Genetic Architecture of Familial Endometriosis: From Heritability to Rare Variant Discovery

This technical guide synthesizes evidence from twin and family aggregation studies to establish the heritable basis of endometriosis, a complex gynecological disorder. Familial clustering and twin concordance data provide foundational evidence for a significant genetic component, with first-degree relatives of affected women facing a 5- to 7-fold increased risk. This evidence underpins the rationale for investigating rare genetic variants that may contribute to the observed familial aggregation. We summarize key quantitative findings, detail core experimental methodologies, and outline essential research tools to facilitate the design and interpretation of studies focused on the role of rare variants in familial endometriosis.

Endometriosis is a common, estrogen-dependent inflammatory condition defined by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, affecting approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women [1]. The disease exhibits clear familial aggregation, a pattern that was initially documented in the 1940s and systematically investigated beginning in the 1980s [2] [1]. Early observations of multiple affected relatives within families suggested a heritable component, challenging the previously held view of endometriosis as a solely environmentally acquired condition. Establishing heritability through twin and family studies is a critical first step in dissecting the genetic architecture of a complex disease. These studies provide the epidemiological evidence that justifies the search for specific genetic factors, including rare variants that may segregate within families and contribute significantly to disease risk, particularly in multiplex pedigrees. Understanding this familial risk is essential for designing targeted genetic studies and for improving clinical risk assessment and genetic counseling.

Quantitative Evidence from Family and Twin Studies

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from major family and twin studies, providing a comparative overview of the evidence for the heritability of endometriosis.

Table 1: Risk of Endometriosis Among Relatives from Familial Aggregation Studies

| Study (Year) | Study Population | Risk in 1st-Degree Relatives | Risk in Control Relatives/General Population | Relative Risk (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simpson et al. (1980) [2] | 123 surgically proven cases | Mothers: 5.9%Sisters: 8.1% | 0.9% | 7-fold |

| Moen & Magnus (1991) [1] | 522 Norwegian cases | Mothers: 3.9%Sisters: 4.8% | Sisters in control group: 0.6% | 6- to 8-fold |

| Coxhead & Thomas (1993) [1] | 64 laparoscopically confirmed cases | 1st-Degree Relatives: 9.4% | 1st-Degree Relatives of Controls: 1.6% | 6-fold |

| Stefansson et al. (2002) [2] [1] | 750 Icelandic women (database study) | Significantly higher kinship coefficient | Lower kinship coefficient in controls | Relative Risk for Sisters: 5.20 |

Table 2: Evidence from Twin Studies and Large-Scale Genetic Analyses

| Study (Year) | Study Design | Key Finding | Implication for Heritability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treloar et al. (1999) [2] | Australian Twin Registry (3,096 twin pairs) | Monozygotic (MZ) Concordance: 2%Dizygotic (DZ) Concordance: 0.6% | Genetic influence accounts for 51% of the latent liability to the disease. |

| Hadfield et al. (1997) [1] | British twin pairs (16 MZ pairs) | High concordance for severe (Stage III-IV) disease among MZ twins. | Suggests a stronger genetic component in severe, potentially familial, forms of endometriosis. |

| Recent GWAS & Methods [3] [4] [5] | Genome-Wide Association Studies & Heritability Estimation | SNP-based heritability estimates and identification of specific risk loci. | Confirms a polygenic basis and allows estimation of additive genetic variance from population data. |

A 2010 retrospective cohort study further supports this trend, reporting endometriosis in 5.9% of first-degree relatives of patients compared to 3.0% in controls, though this less dramatic increase highlights potential variability in study design and population ascertainment [6].

Core Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Familial Aggregation Study Design

Objective: To determine whether the risk of endometriosis is higher among relatives of affected individuals compared to the general population or controls.

Detailed Protocol:

- Proband Ascertainment: Identify individuals (probands) with a confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis. The gold standard for confirmation is surgical visualization (laparoscopy or laparotomy) with histological confirmation by biopsy [6]. Document disease stage (e.g., rAFS classification) and symptom history.

- Family History Elicitation: Collect family history data from probands regarding their first-, second-, and third-degree relatives. This is typically done via structured interviews or detailed questionnaires [6]. Information sought includes:

- Gynecologic surgical history and any endometriosis diagnoses.

- Symptoms suggestive of endometriosis (e.g., chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, infertility).

- For relatives where information is unknown, this should be explicitly recorded to assess potential bias [6].

- Control Group Selection: Recruit a control group of women without endometriosis (confirmed laparoscopically) and elicit family history data from them in an identical manner [6].

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the frequency of endometriosis among first-, second-, and third-degree relatives in both the case and control families.

- Compute the relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) for relatives of cases compared to relatives of controls.

- Statistical tests, such as chi-square analysis, are used to determine if observed differences are significant [6].

- Address potential biases, such as ascertainment bias (families with multiple affected members may be more likely to participate) and reporting bias (cases may be more aware of family history), through study design and statistical adjustments [2].

Twin Study Design

Objective: To partition the phenotypic variance of endometriosis into genetic and environmental components by comparing concordance rates between monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins.

Detailed Protocol:

- Twin Registry Identification: Identify twin pairs from large, population-based twin registries (e.g., the Australian Twin Registry) [2].

- Phenotyping: Determine the endometriosis status of both twins in each pair via self-reported questionnaires, medical record review, or registry data. Zygosity (MZ vs. DZ) is typically determined by standardized questionnaires or genetic testing.

- Concordance Calculation:

- Probandwise Concordance: Calculated as 2C / (2C + D), where C is the number of concordant pairs (both twins affected) and D is the number of discordant pairs (only one twin affected). This represents the probability that a twin is affected given their co-twin is affected.

- Heritability Estimation:

- Classical Model: The correlation of liability is calculated for MZ and DZ twins. Based on the assumption that MZ twins share 100% of their genetic material while DZ twins share 50% on average, structural equation modeling is used to estimate the proportion of phenotypic variance due to:

- Additive Genetic Factors (A)

- Common/Shared Environment (C)

- Unique/Non-Shared Environment (E)

- This ACE model allows for the calculation of heritability (the A component), as demonstrated in the Treloar et al. study which estimated heritability at 51% [2].

- Classical Model: The correlation of liability is calculated for MZ and DZ twins. Based on the assumption that MZ twins share 100% of their genetic material while DZ twins share 50% on average, structural equation modeling is used to estimate the proportion of phenotypic variance due to:

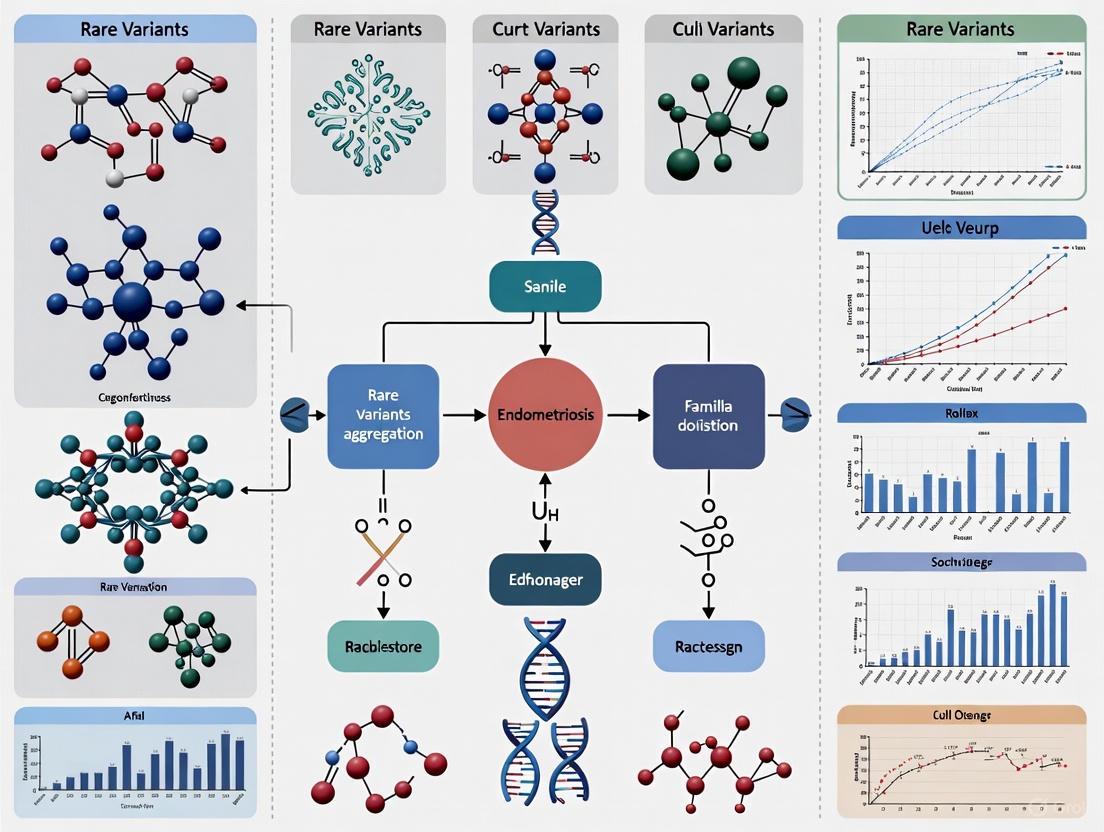

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and core relationships analyzed in both family and twin studies to establish heritability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Endometriosis Genetics

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Tools for Investigating Genetics of Endometriosis

| Research Tool / Reagent | Specific Example / Assay Type | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Isolation Kits | Phenol-chloroform extraction, silica-column based kits (e.g., Qiagen) | Obtain high-quality, high-quantity genomic DNA from blood, saliva, or tissue samples for downstream genetic analyses. |

| Genotyping Microarrays | Illumina Global Screening Array, Infinium Omni5 | Simultaneously genotype hundreds of thousands to millions of common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome for linkage analysis and GWAS. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platforms | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) | Identify common and, crucially, rare coding and regulatory variants across the genome or exome in familial cases. |

| TaqMan Assays / PCR Reagents | Allelic Discrimination Assays, Sanger Sequencing | Validate and fine-map genetic associations identified through GWAS or linkage studies in independent cohorts. |

| Linkage & Association Analysis Software | MERLIN, PLINK, SOLAR | Perform genome-wide linkage analysis in families and association analysis in case-control cohorts to identify disease-linked loci. |

| Heritability Estimation Software | GCTA, BOLT-REML, HEELS, LDSC | Estimate the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by all measured SNPs (SNP heritability) using individual-level or summary statistics data [4] [5] [7]. |

| Bioinformatics Databases | 1000 Genomes Project, gnomAD, UK Biobank, Genomics England | Provide reference data on genetic variation, allele frequencies in different populations, and access to large-scale genotype-phenotype data for analysis [3]. |

| Tetrabenazine-D7 | Tetrabenazine-D7, MF:C19H27NO3, MW:324.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AZ Pfkfb3 26 | AZ Pfkfb3 26, MF:C24H26N4O2, MW:402.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Connecting Familial Aggregation to Rare Variant Research

The consistent evidence from family and twin studies provides a powerful justification for searching for specific genetic variants that drive familial risk. While genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified numerous common variants associated with endometriosis, these typically confer small individual risks and explain only a portion of the heritability [8]. The "missing heritability" and the observation that familial cases often present with more severe disease [1] point toward the contribution of rare variants (with allele frequencies <1-5%) that may have larger effect sizes.

The transition from establishing familial risk to identifying rare variants involves specific methodological shifts:

- From Microarrays to Sequencing: Moving from genotyping arrays that capture common variation to whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing in multiplex families is critical for discovering rare, penetrant variants [3].

- From GWAS to Linkage and Burden Testing: In families, linkage analysis can pinpoint chromosomal regions shared among affected members. Subsequently, burden tests and gene-based aggregation tests can determine if rare variants within a specific gene or pathway are enriched in cases compared to controls.

- Functional Follow-Up: Identified rare variants require functional validation using in vitro and in vivo models to elucidate their impact on gene expression (e.g., effects on regulatory variants near genes like IL-6 and CNR1) [3] and protein function within pathways relevant to endometriosis pathogenesis, such as hormone signaling and immune dysregulation [9].

The following diagram outlines this strategic progression from establishing heritability to the functional characterization of rare variants.

Endometriosis, a chronic, estrogen-driven inflammatory disorder, affects approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women globally, representing over 190 million individuals worldwide [3] [10]. Family and twin studies have consistently demonstrated a substantial genetic component to the disease, with heritability estimates reaching 52% [11]. This strong familial aggregation has motivated extensive genetic research, primarily through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which have successfully identified numerous common variants associated with disease susceptibility. The largest GWAS meta-analysis to date, encompassing 60,674 cases and 701,926 controls, identified 42 significant loci for endometriosis predisposition [12]. These loci implicate genes involved in sex steroid signaling (e.g., ESR1, CYP19A1), developmental pathways (e.g., WNT4), and inflammatory processes, providing valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the condition.

However, a critical limitation persists: these common variants explain only a small fraction of the documented heritability—approximately 26% of the accountable genetic variation [12]. This discrepancy represents the "missing heritability" problem that extends beyond endometriosis to many complex genetic disorders. The solution likely lies in investigating rare genetic variants (typically with minor allele frequency <1%) that are not effectively captured by standard GWAS approaches due to their low frequency and the limited statistical power of these studies to detect them. For familial endometriosis cases showing strong aggregation across generations, rare variants with potentially larger effect sizes may constitute key predisposing factors that have eluded detection through common variant-focused approaches [12].

The Limitations of GWAS and Evidence for Rare Variants

The Architecture of Common Variant Associations

GWAS have fundamentally advanced our understanding of endometriosis genetics by identifying common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of moderate effect. Remarkably, 88% of identified GWAS SNPs reside in non-coding regions (either inter-genic or intronic), suggesting they primarily exert regulatory effects on gene expression rather than altering protein structure [11]. This observation implies that endometriosis susceptibility is heavily influenced by variations in gene regulation, potentially affecting transcriptional dynamics in tissue-specific contexts. A meta-analysis of multiple GWAS datasets confirmed that seven out of nine reported loci showed consistent directional effects across studies and populations, with six reaching genome-wide significance [11].

Table 1: Key Endometriosis Susceptibility Loci Identified Through GWAS

| Locus | Nearest Gene | Function | P-value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7p15.2 | Intergenic | Regulatory | 1.6 × 10â»â¹ | [11] |

| 1p36.12 | WNT4 | Development, steroidogenesis | 1.8 × 10â»Â¹âµ | [11] [13] |

| 12q22 | VEZT | Cell adhesion | 4.7 × 10â»Â¹âµ | [11] [13] |

| 9p21.3 | CDKN2B-AS1 | Cell cycle regulation | 1.5 × 10â»â¸ | [11] |

| 6p22.3 | ID4 | Development | 6.2 × 10â»Â¹â° | [11] |

| 2p25.1 | GREB1 | Estrogen regulation | 4.5 × 10â»â¸ | [11] |

Despite these advances, the polygenic risk scores (PRS) derived from GWAS findings demonstrate limited clinical utility for predictive testing, as they fail to identify many individuals who develop endometriosis, particularly those with severe or familial forms. This limitation stems from the fundamental design of GWAS, which optimally detects common variants (frequency >5%) with small to moderate effects (odds ratios typically <1.5) under the "common disease-common variant" hypothesis [11]. This approach is inherently underpowered to detect rare variants, creating a critical blind spot in our understanding of endometriosis genetics, especially for families showing multigenerational transmission patterns.

Evidence for High-Risk Variants in Familial Aggregation

Several lines of evidence support the role of rare, high-effect variants in familial endometriosis. Linkage studies—a classic approach for identifying rare variants in families—have identified significant linkage peaks on chromosome 10q26 and 7p13-15 [11] [12]. Fine-mapping of the 7p13-15 region revealed association with common variants in NPSR1, but the rare variants potentially responsible for the original linkage signal remain elusive [12]. Additionally, case reports of families with multiple affected women across generations suggest Mendelian-like inheritance patterns in a subset of cases. One notable Greek family included seven affected women across three generations, while Italian and French families have shown similar aggregation patterns [12].

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) of a Finnish family with four affected members across two generations, two of whom also developed high-grade serous carcinoma, revealed three rare candidate predisposing variants segregating with endometriosis: c.1238C>T, p.(Pro413Leu) in FGFR4; c.5065C>T, p.(Arg1689Trp) in NALCN; and c.2086G>A, p.(Val696Met) in NAV2 [12]. The FGFR4 variant was predicted to be deleterious by in silico tools, suggesting a potential pathogenic role. Although further screening of 92 Finnish endometriosis patients did not reveal additional carriers—consistent with the rarity of these variants—this study provides important proof-of-concept that rare coding variants may contribute to familial endometriosis risk.

Classes and Characteristics of Rare Variants in Endometriosis

Copy Number Variants (CNVs)

Copy number variants (CNVs)—deletions or duplications of DNA segments ≥1 kb—represent a major class of structural variation that may contribute to endometriosis risk. CNVs account for more genetic variation in the genome (0.5-1%) than single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, 0.1%) and include more recent mutations of large effect that are not well-captured by SNP arrays [14]. A comprehensive CNV analysis of 2,126 surgically confirmed endometriosis cases and 17,974 population controls of European ancestry identified an average of 1.92 CNVs per individual with an average size of 142.3 kb [14]. While global CNV burden did not differ between cases and controls, several specific CNV regions showed significant association with endometriosis risk.

Table 2: Significantly Associated Copy Number Variants in Endometriosis

| Genomic Location | Gene | Variant Type | P-value | Odds Ratio | Frequency (Cases vs Controls) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8p22 | SGCZ | Deletion | 7.3 × 10â»â´ | 8.5 | 6.9% vs 2.1% |

| 10p12.31 | MALRD1 | Deletion | 5.6 × 10â»â´ | 14.1 | |

| 11q14.1 | Intergenic | Deletion | 5.7 × 10â»â´ | 33.8 | |

| 7q36.2 | DPP6 | SNP association | 0.0045 | ||

| 9q33.1 | ASTN2 | SNP association | 0.0002 |

Notably, the identified CNV loci were detected in 6.9% of affected women compared to only 2.1% in the general population, suggesting that these rare structural variants collectively contribute to disease risk in a subset of patients [14]. The high odds ratios (ranging from 8.5 to 33.8) for the significantly associated CNVs indicate their potentially large effect sizes, consistent with the hypothesis that rare variants often have stronger effects than common variants.

Regulatory Variants and Ancient Introgression

Beyond coding variants, recent evidence suggests that regulatory variants in non-coding regions may significantly contribute to endometriosis susceptibility through effects on gene expression. A study investigating the intersection of ancient genetic regulatory variants and modern environmental pollutants identified six regulatory variants significantly enriched in an endometriosis cohort compared to matched controls [3]. These included co-localized IL-6 variants (rs2069840 and rs34880821) located at a Neandertal-derived methylation site that demonstrated strong linkage disequilibrium and potential immune dysregulation [3]. Variants in CNR1 and IDO1, some of Denisovan origin, also showed significant associations.

These findings propose a novel perspective in which ancient regulatory variants and contemporary environmental exposures converge to modulate immune and inflammatory responses in endometriosis [3]. The preservation of these archaic haplotypes in modern human populations suggests they may have conferred evolutionary advantages, potentially related to enhanced immunity, while now contributing to disease susceptibility in different environmental contexts. This gene-environment interaction model may explain how ancient genetic variants influence modern disease risk, particularly for conditions like endometriosis that involve complex immune and inflammatory pathways.

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTLs) with Tissue-Specific Effects

The integration of endometriosis GWAS findings with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data from relevant tissues provides a powerful approach to understanding the functional consequences of non-coding variants. A recent study analyzing 465 endometriosis-associated variants across six physiologically relevant tissues (uterus, ovary, vagina, colon, ileum, and peripheral blood) revealed striking tissue-specific regulatory patterns [15]. In reproductive tissues, eQTLs predominantly regulated genes involved in hormonal response, tissue remodeling, and adhesion, whereas in intestinal tissues and blood, immune and epithelial signaling genes predominated [15].

This tissue-specific regulatory architecture suggests that endometriosis risk variants may operate through distinct mechanisms in different anatomical contexts, potentially explaining the heterogeneous presentation of the disease. Key regulators identified through this approach included MICB (involved in immune evasion), CLDN23 (angiogenesis), and GATA4 (proliferative signaling). Notably, a substantial subset of regulated genes was not associated with any known pathway, indicating potential novel regulatory mechanisms in endometriosis pathogenesis [15].

Methodological Approaches for Rare Variant Investigation

Study Designs for Familial Aggregation

Investigating rare variants in familial endometriosis requires specialized study designs and analytical approaches. Family-based studies offer several advantages for rare variant discovery, including enhanced genetic homogeneity and increased frequency of rare variants due to shared ancestry. The typical workflow begins with the identification of multiplex families (multiple affected relatives) with severe or early-onset disease, followed by genetic analysis using hypothesis-free approaches.

Diagram 1: Rare variant investigation workflow (53 characters)

The selection of families with strong aggregation of endometriosis increases the likelihood of identifying rare, penetrant variants. Subsequent segregation analysis within families helps establish co-segregation of candidate variants with disease status, providing evidence for their potential pathogenicity. Independent validation in additional familial cases or population-based cohorts is essential to distinguish true associations from false positives, given the high number of rare variants present in every genome.

Genomic Technologies and Analytical Frameworks

Advanced genomic technologies are critical for comprehensive rare variant detection. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) provides cost-effective coverage of protein-coding regions, where approximately 85% of disease-causing mutations are located, while whole-genome sequencing (WGS) offers a completely unbiased approach that captures both coding and non-coding variation, including regulatory elements [12]. The 100,000 Genomes Project has demonstrated the utility of WGS for identifying regulatory variants in endometriosis, analyzing non-coding regions that are typically poorly covered by exome sequencing [3].

For CNV detection, high-density genotyping arrays combined with sophisticated algorithms (e.g., PennCNV) can identify structural variants, though stringent quality filters are essential to reduce false positives—from 77.7% to 7.3% in one study [14]. Technical validation using orthogonal methods such as array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) or digital PCR is recommended for confirmed CNV calls.

Analytical frameworks for rare variant association include gene-based burden tests that aggregate multiple rare variants within a gene to increase statistical power, and family-based association methods that leverage within-family transmission information. Functional annotation using tools like Ensembl's Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) helps prioritize variants based on their predicted impact on protein function or regulatory elements [3] [15].

Table 3: Experimental Approaches for Rare Variant Analysis

| Method | Application | Resolution | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Exome Sequencing | Coding variant discovery | Single nucleotide | Cost-effective for coding regions; interpretable results | Misses non-coding variants |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing | Genome-wide variant discovery | Single nucleotide | Comprehensive; captures non-coding variation | Higher cost; computational burden |

| High-Density SNP Arrays | CNV detection | >1 kb | Cost-effective for large samples; established pipelines | Limited resolution; false positives |

| Cytoscan HD | CNV validation | >50 kb | High sensitivity; gold standard | Low throughput; expensive |

Functional Validation Strategies

Establishing the functional consequences of rare variants is essential for confirming their pathogenicity. Multiple experimental approaches can be employed, depending on the predicted effect of the variant and the implicated gene. For coding variants, in vitro functional assays can assess impacts on protein function, localization, or interaction partners. For regulatory variants, reporter gene assays (e.g., luciferase) can quantify effects on transcriptional activity, while electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) can detect altered transcription factor binding.

Advanced models such as patient-derived organoids or genome-edited cell lines (using CRISPR/Cas9) provide more physiologically relevant systems for studying variant effects in appropriate cellular contexts. Integration with epigenetic data from relevant tissues (e.g., endometrial epithelium or stroma) can help prioritize non-coding variants with evidence of regulatory function in disease-relevant cell types.

Mendelian randomization approaches can also provide evidence for causal relationships between identified genes and endometriosis risk. For example, a recent Mendelian randomization study identified RSPO3 as a potential causal protein in endometriosis, with validation showing elevated RSPO3 levels in plasma and tissues of patients compared to controls [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Rare Variant Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina HumanOmniExpress | High-density genotyping | CNV detection [14] | 551,732 SNPs; genome-wide coverage |

| CRLMM algorithm | Signal intensity analysis | CNV calling from intensity data [14] | Reduces false positives; quality metrics |

| PennCNV | CNV detection | Genome-wide CNV analysis [14] | Hidden Markov Model; population-based |

| GTEx Database v8 | eQTL reference | Tissue-specific regulatory effects [15] | 54 tissues; normalized expression data |

| Ensembl VEP | Variant annotation | Functional consequence prediction [3] [15] | Multiple consequence types; regulatory features |

| SOMAscan Proteomics | Protein quantification | pQTL studies [16] | 4,907 proteins; high-throughput |

| Human R-Spondin3 ELISA Kit | Protein validation | RSPO3 level confirmation [16] | Quantitative; plasma/tissue samples |

| Liproxstatin-1 hydrochloride | Liproxstatin-1 hydrochloride, MF:C19H22Cl2N4, MW:377.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Candesartan-d4 | Candesartan-d4, MF:C24H20N6O3, MW:444.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The investigation of rare genetic variants represents a crucial frontier in endometriosis genetics, offering the potential to explain the "missing heritability" not accounted for by common variants and to identify novel biological pathways for therapeutic targeting. Evidence from CNV studies, whole-exome sequencing of familial cases, and analyses of regulatory variants all support the contribution of rare variants to endometriosis susceptibility, particularly in severe or familial forms. These variants often have larger effect sizes than common variants and may point more directly to causal genes and pathways.

Future research directions should include larger-scale sequencing studies specifically focused on familial endometriosis, improved functional annotation of non-coding variants using epigenomic data from disease-relevant cell types, and development of multi-omic integration frameworks that combine genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data. The development of model systems that recapitulate the tissue-tissue interactions important in endometriosis pathogenesis will be essential for validating the functional consequences of rare variants and testing potential therapeutic interventions.

As our understanding of the genetic architecture of endometriosis evolves to encompass both common and rare variants, we move closer to precision medicine approaches that can stratify patients based on their underlying genetic profile and offer targeted therapies matched to specific molecular subtypes. For the millions of women affected by endometriosis, particularly those with strong family histories, these advances offer hope for improved diagnosis, more effective treatments, and ultimately prevention strategies based on genetic risk assessment.

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity, affecting approximately 10% of women of reproductive age worldwide [17]. The disease demonstrates significant familial aggregation, with first-degree relatives of affected women exhibiting a five- to seven-fold increased risk compared to the general population [18]. Familial cases often present with distinct clinical characteristics, including earlier disease onset and more severe symptoms than sporadic cases [18]. This whitepaper examines the phenotypic and genetic characteristics of familial endometriosis, with particular emphasis on the role of rare variants in disease aggregation.

Family-based studies provide crucial insights into the genetic architecture of complex diseases. Research indicates that despite genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identifying multiple common variants associated with endometriosis risk, these account for only a fraction of the estimated 50% heritability [18]. This "missing heritability" suggests an important role for rare variants with potentially larger effect sizes, particularly in multiplex families with strong disease aggregation [19] [18]. Understanding these rare variants offers promise for elucidating the molecular pathogenesis of endometriosis and identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Clinical Characterization of Familial Endometriosis

Comparative Phenotypic Profiles

Familial endometriosis cases demonstrate quantifiable differences in clinical presentation compared to sporadic cases. The table below summarizes key clinical characteristics based on current literature:

Table 1: Clinical Characteristics of Familial Versus Sporadic Endometriosis

| Clinical Feature | Familial Endometriosis | Sporadic Endometriosis | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Onset | Earlier presentation | Later presentation | [18] |

| Symptom Severity | More severe symptoms | Variable severity | [18] |

| Risk to First-Degree Relatives | 5-7 times increased risk | Population-level risk | [18] |

| Genetic Architecture | Potential rare variants with larger effects | Common variants with small effects | [19] [18] |

Comorbidity Profiles

Recent large-scale studies have revealed that women with endometriosis have a 30-80% increased risk of developing various autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, coeliac disease, osteoarthritis, and psoriasis [9]. Genetic analyses have demonstrated correlations between endometriosis and several of these immune conditions, suggesting a shared biological basis that may be particularly relevant in familial cases [9]. This comorbidity profile extends to other gynecological conditions, with epidemiological meta-analysis across 402,868 women suggesting at least a doubling of UL diagnosis risk among those with endometriosis history [20].

Genetic Architecture of Familial Endometriosis

Common Variants from GWAS

Genome-wide association studies have identified multiple common variants associated with endometriosis risk. A meta-analysis of 11,506 cases and 32,678 controls confirmed genome-wide significant associations at seven loci, with most showing stronger effect sizes among Stage III/IV cases [11]. These include:

- rs12700667 on 7p15.2

- rs7521902 near WNT4

- rs10859871 near VEZT

- rs1537377 near CDKN2B-AS1

- rs7739264 near ID4

- rs13394619 in GREB1 [11]

Despite these successes, common variants identified through GWAS explain only a limited proportion of disease heritability [19]. Most associated variants reside in non-coding regions, suggesting regulatory functions that may influence gene expression in tissue-specific manners [15] [11].

Rare Variants in Familial Aggregation

The search for rare variants in endometriosis has been facilitated by advanced sequencing technologies. An exome-array analysis of 9,004 cases and 150,021 controls found limited evidence for protein-modifying variants with moderate or large effect sizes, suggesting that rare coding variants may exist primarily in specific populations or high-risk families [19]. This highlights the importance of family-based studies for identifying rare variants.

Table 2: Prioritized Candidate Genes from Familial Whole-Exome Sequencing

| Gene | Variant | Protein Effect | Proposed Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMB4 | c.3319G>A | p.Gly1107Arg | Component of basement membranes; cancer growth | [18] |

| EGFL6 | c.1414G>A | p.Gly472Arg | Endothelial cell signaling; angiogenesis | [18] |

| NAV3 | Not specified | Not specified | Cytoskeletal regulation; neuronal development | [18] |

| ADAMTS18 | Not specified | Not specified | Extracellular matrix proteolysis | [18] |

| SLIT1 | Not specified | Not specified | Axon guidance; cell migration | [18] |

| MLH1 | Not specified | Not specified | DNA mismatch repair | [18] |

A recent whole-exome sequencing study of a multigenerational family with multiple affected members identified 36 co-segregating rare variants, with six missense variants in genes associated with cancer growth prioritized as top candidates [18]. The top candidates were LAMB4 and EGFL6, with variants in NAV3, ADAMTS18, SLIT1, and MLH1 potentially contributing to disease through synergistic and additive models [18].

Methodological Framework for Familial Endometriosis Research

Family-Based Study Designs

Family-based studies provide a powerful approach for identifying rare variants in endometriosis. The typical workflow involves:

Figure 1: Family-Based Rare Variant Discovery Workflow

Whole Exome Sequencing Protocol

Detailed methodology for identifying rare variants in familial endometriosis cases:

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect peripheral blood samples from multiple affected family members across generations

- Extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes

- Quality control: assess DNA purity and concentration [18]

Whole Exome Sequencing:

- Platform: Illumina sequencing platform

- Coverage: Average coverage of 100×

- Quality metrics: >90% of bases exceeding Q30, coverage uniformity >80% [18]

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Read alignment: BWA with human GRCh37/hg19 reference genome

- Duplicate removal and variant calling: FreeBayes version 1.3.7

- Variant filtering: Focus on rare (MAF < 0.01), missense, frameshift, and stop variants

- Co-segregation analysis: Identify variants shared among affected family members [18]

Functional Validation Approaches

Experimental Validation of Candidate Genes:

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for protein quantification in plasma

- Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) for gene expression analysis

- Immunohistochemistry for protein localization in tissues

- Western blotting for protein expression confirmation [16]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Familial Endometriosis Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Specific Example | Application in Familial Endometriosis Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Array | Illumina HumanCoreExome BeadChip | Genotyping of common and exonic variants in large cohorts [19] |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina Sequencing Platform | Whole exome sequencing of multigenerational families [18] |

| Variant Caller | FreeBayes v1.3.7 | Identification of sequence variants from WES data [18] |

| ELISA Kit | Human R-Spondin3 ELISA Kit | Quantitative measurement of candidate protein levels [16] |

| Bioinformatic Tool | enGenome-Evai and Varelect | Annotation and prioritization of rare genetic variants [18] |

| Association Software | RareMetal/RareMetalWorker | Single-variant and gene-based association tests [19] |

Biological Pathways and Mechanisms

Signaling Pathways in Familial Endometriosis

Familial endometriosis research has revealed several key biological pathways that may be influenced by rare genetic variants:

Figure 2: Biological Pathways in Familial Endometriosis Pathogenesis

Tissue-Specific Regulatory Mechanisms

Recent research integrating endometriosis-associated variants with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data from six physiologically relevant tissues (uterus, ovary, vagina, colon, ileum, and peripheral blood) has demonstrated tissue-specific regulatory effects [15]. Key findings include:

- In reproductive tissues (ovary, uterus, vagina): enrichment of genes involved in hormonal response, tissue remodeling, and adhesion

- In intestinal tissues (colon, ileum) and peripheral blood: predominance of immune and epithelial signaling genes

- Key regulators such as MICB, CLDN23, and GATA4 consistently linked to hallmark pathways including immune evasion, angiogenesis, and proliferative signaling [15]

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Drug Target Discovery

Mendelian randomization approaches integrating large-scale GWAS data with proteomic and metabolomic datasets have identified potential therapeutic targets for endometriosis. Recent studies have found:

- RSPO3 and FLT1 as potentially associated with endometriosis within the proteome

- External validation and colocalization analysis confirmed robustness of association with RSPO3 [16]

- These findings suggest RSPO3 may represent a new target for endometriosis treatment [16]

Personalized Medicine Approaches

The characterization of familial endometriosis cases with earlier onset and severe symptoms enables new strategies for personalized medicine:

- Polygenic risk scores incorporating both common and rare variants for risk prediction

- Targeted therapies based on specific genetic variants and pathways affected in different patient subgroups

- Repurposing existing treatments across endometriosis and comorbid immune conditions based on shared genetic architecture [9]

Future research directions should include larger family-based sequencing studies, functional characterization of identified rare variants, development of model systems for testing therapeutic interventions, and integration of multi-omics data for comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms.

Endometriosis, a chronic inflammatory condition affecting approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women globally, demonstrates a significant familial aggregation, with first-degree relatives of affected individuals facing a four- to ten-fold increased risk [21] [8]. Twin studies indicate heritability may be as high as 50% [3] [21], providing compelling evidence for a substantial genetic component. Historically, the precise inheritance patterns have been elusive, but emerging genomic research increasingly supports a polygenic model for familial endometriosis, characterized by the combined effects of multiple common and rare genetic variants [22] [8]. This model moves beyond the search for a single causative gene and instead investigates how an accumulation of risk alleles across numerous loci, each with modest effect, contributes to disease susceptibility.

This technical guide explores the evidence supporting this polygenic model within the specific context of familial endometriosis aggregation. A key focus is the emerging role of rare genetic variants, which are increasingly hypothesized to contribute significantly to disease risk in multi-generational families, potentially working in concert with common risk variants identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [22]. We synthesize findings from recent family-based studies, biobank analyses, and advanced combinatorial analytics to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of the methodologies, evidence, and pathogenic mechanisms underpinning this complex inheritance pattern.

Evidence for a Polygenic Model in Familial Endometriosis

Key Genetic Studies Supporting Polygenic Inheritance

Table 1: Summary of Key Studies Supporting a Polygenic Model for Familial Endometriosis

| Study Type | Key Findings | Implicated Genes/Pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family-Based WES (Multi-generational) | Identified 36 co-segregating rare variants in a 4-generation family; supports polygenic rather than monogenic inheritance. | LAMB4, EGFL6, NAV3, ADAMTS18, SLIT1, MLH1 (roles in cell growth, ECM remodeling, cancer). |

[22] |

| Combinatorial Analytics (UK Biobank & All of Us) | Identified 1,709 multi-SNP disease signatures (2,957 unique SNPs); 75 novel genes discovered beyond GWAS hits. | Pathways: Cell adhesion, proliferation/migration, cytoskeleton remodeling, angiogenesis, fibrosis, neuropathic pain. | [23] |

| Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) & Comorbidity (UKB & Estonian Biobank) | PRS interacts with comorbidities (e.g., uterine fibroids, heavy bleeding); greater comorbidity burden correlates with PRS in controls. | Highlights interaction between polygenic risk and clinical symptoms/comorbidities. | [24] |

| Clinical Phenotype & Family History (Retrospective Cohort) | Patients with a positive family history had 3.5x higher recurrence risk (adjusted OR), more severe pain, and lower conception rates. | Demonstrates the link between familial aggregation and exacerbated clinical manifestations. | [21] |

The Role of Rare Variants in Familial Aggregation

While GWAS have successfully identified numerous common variants associated with endometriosis, these explain only a limited fraction of the disease's heritability, a challenge known as the "missing heritability" problem [23] [8]. This gap has directed attention to the role of rare variants (typically with a minor allele frequency <1%) in families showing strong disease aggregation.

A pivotal study employing whole-exome sequencing (WES) in a four-generation Italian family affected by endometriosis uncovered 36 rare co-segregating variants [22]. Instead of a single causative mutation, the study found multiple rare variants in genes like LAMB4, EGFL6, NAV3, ADAMTS18, SLIT1, and MLH1. These genes are involved in biological pathways crucial for cell adhesion, extracellular matrix remodeling, and tissue organization—processes fundamental to the establishment and survival of endometriotic lesions [22]. This finding provides direct evidence for an oligogenic or polygenic model in familial contexts, where the aggregate burden of several rare, moderately penetrant variants contributes to disease susceptibility.

Further supporting this, a combinatorial analytics study of the UK Biobank identified complex disease signatures comprising combinations of 2-5 SNPs [23]. This approach, which moves beyond single-variant analysis, found that high-frequency, reproducible genetic combinations were linked to 75 novel genes not previously associated with endometriosis in large-scale GWAS. These genes point to new mechanisms, including autophagy and macrophage biology, suggesting that rare variants in these pathways may be particularly relevant in subsets of patients or families [23].

Table 2: Characterized Novel Genes from Combinatorial Analysis

| Gene | Potential Role in Endometriosis Pathogenesis | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Gene A | Involvement in autophagic processes within endometrial stromal cells. | Novel |

| Gene B | Regulation of macrophage polarization and inflammatory response. | Novel |

| Gene C | Cytoskeleton remodeling affecting cell migration and adhesion. | Novel |

| ... (etc. for 6 more genes) | ... | ... |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Polygenic Inheritance

Whole-Exome and Whole-Genome Sequencing in Family Cohorts

Objective: To identify rare, penetrant coding and regulatory variants that co-segregate with endometriosis across multiple generations in a single family or several families.

Workflow:

- Participant Selection: Recruit multi-generational families with a high burden of endometriosis (e.g., multiple affected sisters, their mother, grandmother, and daughters) [22]. Unaffected family members serve as internal controls.

- DNA Extraction & Sequencing: Perform high-quality DNA extraction from blood or saliva samples. Conduct WES or WGS to sequence the entire exome or genome.

- Variant Calling & Filtering:

- Call variants (SNVs, InDels) from sequence data using tools like GATK.

- Filter against population databases (e.g., gnomAD) to retain rare variants (MAF < 0.01).

- Annotate variants for functional impact (e.g., using Ensembl VEP).

- Co-segregation Analysis: Identify variants that are present in all affected family members and absent (or present at a much lower frequency) in unaffected members.

- Prioritization & Validation:

- Prioritize variants based on predicted pathogenicity (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen-2), gene function, and relevance to known endometriosis pathways (e.g., cell adhesion, hormone signaling) [22].

- Validate shortlisted variants using Sanger sequencing.

- Conduct functional studies in cell or animal models to confirm biological impact (e.g., impact on gene expression via eQTL analysis) [15].

Combinatorial Analytics for Multi-SNP Signature Identification

Objective: To discover combinations of genetic variants (common and rare) that collectively confer disease risk, which are missed by single-variant GWAS analyses.

Workflow:

- Dataset Curation: Utilize large-scale genetic datasets from biobanks (e.g., UK Biobank, All of Us). Select endometriosis cases and controls, accounting for population structure [23].

- Combinatorial Analysis: Use a specialized platform (e.g., PrecisionLife) to analyze the dataset. The algorithm tests for combinations of 2-5 SNPs that are significantly associated with case/control status.

- Signature Validation & Reproducibility:

- Test the identified disease signatures in an independent, multi-ancestry cohort (e.g., All of Us) to assess reproducibility.

- Calculate reproducibility rates, particularly for high-frequency signatures.

- Functional Annotation & Pathway Analysis:

- Map SNPs from reproducible signatures to genes.

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., with MSigDB Hallmark, Cancer Hallmarks) to identify biological processes dysregulated in endometriosis (e.g., cell adhesion, proliferation, angiogenesis) [15] [23].

- Integrate with eQTL data (e.g., from GTEx) to determine if risk variants regulate gene expression in disease-relevant tissues (uterus, ovary, etc.) [15].

Integration of eQTL and Functional Genomic Data

Objective: To bridge the gap between genetic association and biological mechanism by determining how risk variants, especially those in non-coding regions, regulate gene expression.

Workflow:

- Variant Selection: Curate a set of endometriosis-associated variants from GWAS and family studies [15].

- Tissue-Relevant eQTL Mapping: Cross-reference these variants with tissue-specific eQTL datasets from repositories like GTEx. Focus on tissues relevant to endometriosis pathophysiology: uterus, ovary, vagina, sigmoid colon, ileum, and peripheral blood [15] [25].

- Prioritization of Candidate Genes: Prioritize genes based on:

- The strength of the eQTL association (FDR < 0.05).

- The magnitude of the effect on expression (slope value).

- Being regulated by multiple risk variants.

- Functional Interpretation: Input the list of eQTL-regulated genes into functional annotation tools (e.g., MSigDB Hallmark, Cancer Hallmarks) to identify enriched biological pathways (e.g., "immune evasion," "angiogenesis," "hormonal response") [15]. This reveals the molecular pathways through which genetic risk is mediated.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Investigating Polygenic Inheritance

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | GTEx Portal (v8), gnomAD, Ensembl VEP, 1000 Genomes, LDlink | Provides tissue-specific eQTL data, population allele frequencies, functional variant annotation, and linkage disequilibrium information [15] [3]. |

| Biobanks & Cohort Data | UK Biobank, All of Us, Estonian Biobank, Genomics England 100,000 Genomes | Sources of large-scale genetic and phenotypic data for discovery and validation studies [24] [23]. |

| Analytical Software & Platforms | PrecisionLife Combinatorial Analytics, PLINK, R/Bioconductor | For performing combinatorial association analysis, standard GWAS QC, and statistical genetics analyses [23]. |

| Pathway Analysis Tools | MSigDB Hallmark Gene Sets, Cancer Hallmarks Platform | Functional annotation and biological pathway enrichment analysis for candidate gene lists [15] [23]. |

| Sequencing & Genotyping | Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS), Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES), SNP microarrays | Identifying rare variants in families (WGS/WES) and common variants in populations (microarrays) [3] [22]. |

The collective evidence from family-based sequencing, combinatorial analytics, and integrated functional genomics solidly supports a polygenic model for the familial aggregation of endometriosis. This model incorporates the effects of both common variants, identified through GWAS and captured in PRS, and, crucially, multiple rare variants that appear to have a more pronounced role in multi-generational families [23] [22]. The disease etiology is further complicated by interactions between this polygenic risk and environmental exposures, such as endocrine-disrupting chemicals, as well as comorbid conditions [3] [24].

For drug development, this refined understanding underscores that endometriosis is not a single disease but a spectrum of disorders with varying genetic underpinnings. The future of therapeutics lies in targeting specific pathways—such as those involved in cell adhesion, neuropathic pain, or macrophage function—that are dysregulated in specific genetic subgroups [23]. Furthermore, the genetic signatures and polygenic risk models emerging from this research hold promise for de-risking clinical trials by enabling better patient stratification and paving the way for a precision medicine approach to treating this complex condition.

Endometriosis, defined by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, is a common, chronic gynecological condition affecting approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women globally. It is a complex disease characterized by chronic pelvic pain, severe dysmenorrhea, and subfertility [13] [26]. Family and twin studies have consistently demonstrated a strong heritable component, with genetic factors estimated to account for about 52% of the variation in disease liability [27]. The collaborative International Endogene Study, along with other research initiatives, has adopted a positional-cloning approach to identify genomic regions harboring disease-predisposing genes, particularly focusing on families with multiple affected members. This strategy has been fruitful in identifying significant susceptibility loci, with chromosomes 7p13-15 and 10q26 emerging as regions of major interest for understanding the role of rare, high-penetrance variants in familial endometriosis aggregation [28] [26].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Endometriosis Genetic Studies

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Heritability | ~52% of liability variance [27] |

| Familial Risk | Increased relative risk of ~2.34 for sisters of affected women [27] |

| Study Approach | Positional cloning via linkage analysis in multiplex families |

| Primary Study Populations | 1,176 families (931 Australian, 245 UK) with ≥2 affected members [26] |

| Key Identified Loci | Chromosome 7p13-15, Chromosome 10q26 [28] [26] |

Chromosome 7p13-15: A High-Penetrance Susceptibility Locus

Linkage Evidence and Genetic Characteristics

The investigation of chromosome 7p13-15 represents a breakthrough in endometriosis genetics as the first report suggesting a high-penetrance susceptibility locus with near-Mendelian inheritance patterns. In the initial analysis of 52 families from the Oxford dataset comprising at least three affected women, researchers observed a non-parametric linkage score (Kong & Cox LOD) of 3.52 on chromosome 7p, achieving genome-wide significance (P = 0.011) [28]. Parametric analysis further strengthened this evidence, revealing an MOD score of 3.89 at 65.72 cM (D7S510) for a dominant model with reduced penetrance. When expanding the analysis to include the Australian dataset (196 families), the combined data analysis continued to support linkage to this region, with a parametric MOD score of 3.30 at D7S484 for a recessive model with high penetrance (empirical significance: P = 0.035) [28]. Critical recombinant mapping narrowed the probable region of linkage to overlapping intervals of 6.4 Mb and 11 Mb, containing 48 and 96 genes, respectively, providing a focused target for subsequent gene identification efforts.

Fine-Mapping and Candidate Gene Evaluation

Following the linkage discovery, research efforts concentrated on fine-mapping the 7p13-15 region and evaluating plausible candidate genes based on their biological functions in endometrial development. Investigators prioritized three strong candidate genes—INHBA (inhibin subunit beta A), SFRP4 (secreted frizzled related protein 4), and HOXA10 (homeobox A10)—all located within or near the linkage peak and known to play roles in endometrial development and function [29]. Using Sanger sequencing, researchers screened the coding regions and parts of the regulatory regions of these genes in 47 cases from the 15 families that contributed most significantly to the linkage signal (Z(mean) ≥ 1). The analysis identified 11 variants, 5 of which were common (minor allele frequency > 0.05) and showed no significant frequency difference compared to reference populations. The remaining six rare variants were deemed unlikely to be individually or cumulatively responsible for the observed linkage signal [29]. This systematic exclusion highlighted the complexity of the region and suggested that either regulatory elements of these genes or other genes in the region might harbor the causal variants.

Breakthrough: Identification of NPSR1 and Therapeutic Implications

Substantial progress in understanding the 7p13-15 locus came from advanced sequencing analyses and cross-species validation. Researchers performed in-depth sequencing of families with strong linkage to chromosome 7p13-15, which revealed rare variants in the NPSR1 (neuropeptide S receptor 1) gene [30]. Most women carrying these rare NPSR1 variants had stage III/IV disease. Validation studies in rhesus macaques with spontaneous endometriosis provided further supportive evidence for the involvement of this gene. Subsequently, a large case-control study of over 11,000 women identified a specific common variant in the NPSR1 gene also associated with stage III/IV endometriosis [30]. This discovery has significant translational implications, as researchers used an NPSR1 inhibitor to block protein signaling in cellular assays and mouse models of endometriosis, resulting in reduced inflammation and abdominal pain. This identifies NPSR1 as a promising nonhormonal therapeutic target for future drug development.

Table 2: Key Findings for Chromosome 7p13-15 Locus

| Analysis Type | Key Finding | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Linkage (Oxford) | Non-parametric LOD = 3.52 | Genome-wide P = 0.011 |

| Parametric Linkage (Oxford) | MOD score = 3.89 at D7S510 | Dominant model with reduced penetrance |

| Combined Dataset Analysis | MOD score = 3.30 at D7S484 | Empirical P = 0.035 (recessive model) |

| Candidate Gene Screening | 11 variants in INHBA, SFRP4, HOXA10 | None accounted for linkage signal |

| NPSR1 Identification | Rare and common variants in NPSR1 | Associated with stage III/IV disease |

Chromosome 10q26: A Significant Locus with Subtype Heterogeneity

Genome-Wide Significant Linkage and Refinement

Chromosome 10q26 was the first region to demonstrate significant linkage in a genome-wide scan of endometriosis. The initial analysis of 1,176 affected sister-pair families revealed a maximum LOD score (MLS) of 3.09 on chromosome 10q26, reaching genome-wide significance (P = 0.047) [26] [31]. This finding was particularly notable as it represented the first report of linkage to a major locus for endometriosis. To refine this linkage signal, researchers employed latent class analysis (LCA) to identify more genetically homogeneous subgroups based on symptoms and disease characteristics. The LCA revealed a two-class solution as most parsimonious, with the primary discriminating factor being subfertility [27]. Class 1 families (51.7% of linkage families) typically presented without subfertility (91%) but with more frequent pelvic pain (80.3%), while Class 2 families (48.3%) showed higher rates of subfertility. This stratification proved critical for enhancing the linkage signal when focusing on fertility-related subtypes.

Fine-Mapping and Association Studies

The 10q26 linkage region spans a substantial genomic interval, requiring extensive fine-mapping to identify specific association signals. Researchers conducted a high-density association study analyzing 11,984 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across chromosome 10 in 1,144 familial cases and 1,190 controls [27]. This approach identified three independent association signals: at 96.59 Mb (rs11592737, P=4.9 × 10â»â´), 105.63 Mb (rs1253130, P=2.5 × 10â»â´), and 124.25 Mb (rs2250804, P=9.7 × 10â»â´). Importantly, analyses restricted to samples from the linkage families supported the association at all three regions. Subsequent replication efforts in an independent sample of 2,079 cases and 7,060 population controls confirmed only the signal at 96.59 Mb, located within the cytochrome P450 subfamily C (CYP2C19) gene [27]. This gene, involved in metabolizing various compounds including steroids, thus emerged as a compelling candidate for further investigation in endometriosis susceptibility.

Biological Implications of CYP2C19

The association of CYP2C19 with endometriosis risk presents intriguing biological implications. As a member of the cytochrome P450 family, CYP2C19 participates in the metabolism of exogenous chemicals and endogenous compounds, potentially including reproductive hormones [27]. Altered function or expression of this enzyme could influence hormonal balance, inflammatory responses, or the metabolism of environmental toxicants that may contribute to endometriosis pathogenesis. The specific variant identified (rs11592737) may affect gene regulation or function in a way that modifies disease risk, particularly in the context of subfertility-related endometriosis subtypes. However, further functional characterization is necessary to fully elucidate the mechanistic role of CYP2C19 in endometriosis development and progression.

Table 3: Key Findings for Chromosome 10q26 Locus

| Analysis Type | Key Finding | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Linkage | MLS = 3.09 | Genome-wide P = 0.047 |

| Stratified Analysis | Increased LOD to 3.62 with subfertility stratification | - |

| Association Signal 1 | rs11592737 in CYP2C19 at 96.59 Mb | P = 4.9 × 10â»â´ (replicated) |

| Association Signal 2 | rs1253130 at 105.63 Mb | P = 2.5 × 10â»â´ (not replicated) |

| Association Signal 3 | rs2250804 at 124.25 Mb | P = 9.7 × 10â»â´ (not replicated) |

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Family Ascertainment and Phenotypic Assessment

The foundational methodology underlying these discoveries involved systematic family recruitment and rigorous phenotypic characterization. The International Endogene Study collected 1,176 families with at least two members (primarily affected sister pairs) with surgically confirmed endometriosis [26]. Surgical confirmation was essential to ensure diagnostic accuracy, as endometriosis cannot be reliably diagnosed without visual inspection. Disease staging employed the revised American Fertility Society (rAFS) classification system, though researchers often simplified this to a two-stage system for practical application: Stage A (rAFS I-II or minimal ovarian disease) and Stage B (rAFS III-IV) [27]. Participants provided detailed information on symptoms including pelvic pain severity and subfertility (defined as failure to conceive after 12 months of trying). This comprehensive phenotyping enabled subsequent stratification analyses that proved crucial for enhancing genetic homogeneity.

Genotyping and Linkage Analysis Methodology

Genotyping protocols varied across studies but shared common quality control measures. For the initial genome-wide linkage scan, researchers typically used microsatellite markers spaced throughout the genome [26]. Non-parametric linkage analyses employed affected-only methods, calculating exponential LOD (expLOD) scores using specialized software such as the ALLEGRO package [27]. To address genetic heterogeneity, researchers implemented ordered subset analyses (OSA), stratifying families based on clinical features like subfertility to identify more genetically homogeneous subgroups [27]. For fine-mapping studies, high-density SNP arrays (e.g., Illumina Infinium platforms) genotyped thousands of markers across regions of interest. Stringent quality control measures included excluding SNPs with >5% missing genotypes, violating Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P < 1×10â»â´ in controls), or showing differential missingness between cases and controls [27].

Association Analysis and Replication Strategies

Association testing in fine-mapping studies typically employed Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) tests to account for potential population stratification by treating different recruitment centers as strata [27]. Researchers assessed association significance through permutation testing (e.g., 10,000 replicates) to establish empirical P-values. For replication studies, independent sample sets were genotyped, often using different technology platforms (e.g., Illumina Human670Quad Beadarrays), requiring careful quality control and imputation to harmonize datasets. Meta-analysis approaches then combined results from discovery and replication phases to enhance statistical power [27]. When candidate genes were identified, Sanger sequencing of coding regions and regulatory elements in familial cases helped identify potentially causal rare variants, with functional prediction tools (SIFT, Polyphen) assessing the potential impact of non-synonymous changes [32] [29].

Diagram Title: Endometriosis Genetic Study Workflow

Pathway Integration and Functional Validation

The integration of genetic findings with biological pathways has provided insights into endometriosis mechanisms. The identification of NPSR1 on chromosome 7p13-15 points to neuroimmune pathways in endometriosis pathophysiology. NPSR1 encodes a G-protein coupled receptor that modulates inflammatory responses and pain signaling [30]. Similarly, the association of CYP2C19 on chromosome 10q26 suggests potential involvement in hormonal metabolism and detoxification pathways. These findings align with the understanding of endometriosis as an estrogen-dependent inflammatory condition.

Diagram Title: Proposed Pathways for Endometriosis Genes

Functional validation studies have been crucial for establishing biological relevance. For NPSR1, researchers used specific inhibitors in cellular assays and mouse models of endometriosis, demonstrating reduced inflammation and abdominal pain [30]. This not only validated the genetic association but also identified a potential therapeutic target. For other loci, functional genomic approaches including gene expression profiling, epigenetic analyses, and integration with multi-omics data have helped elucidate potential mechanisms [13]. These functional studies are essential for translating statistical genetic associations into understanding of disease biology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Endometriosis Genetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Affected Sister-Pair Families | Linkage analysis to identify susceptibility loci | 1,176 families with ≥2 affected members [26] |

| Surgically Confirmed Cases | Ensure phenotypic accuracy and reduce heterogeneity | All cases diagnosed via laparoscopy [26] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Obtain high-quality genomic DNA | Blood samples for DNA extraction [27] |

| Microsatellite Markers | Genome-wide linkage scanning | Initial genome scan with microsatellites [26] |

| SNP Genotyping Arrays | Fine-mapping and association studies | Illumina Infinium iSelect custom platform [27] |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Candidate gene validation and rare variant detection | Screening INHBA, SFRP4, HOXA10 coding regions [29] |

| Quality Control Software | Ensure data integrity and remove artifacts | PLINK for QC filters [27] |

| Linkage Analysis Software | Calculate LOD scores and identify linked regions | ALLEGRO package for exponential LOD scores [27] |

| Association Analysis Tools | Test for allele frequency differences | Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests in PLINK [27] |

| NPSR1 Inhibitors | Functional validation of candidate gene | Used in cellular and mouse model studies [30] |

| Brimonidine-d4 | Brimonidine-d4, MF:C11H10BrN5, MW:296.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sutidiazine | Sutidiazine|CAS 1821293-40-6|Antimalarial Research Agent | Sutidiazine is a novel triaminopyrimidine antimalarial candidate with oral activity. This product is for research use only and not for human consumption. |

The identification and characterization of chromosomes 7p13-15 and 10q26 as susceptibility loci for endometriosis represent significant advances in understanding the genetic architecture of this complex disorder. The findings from these linkage studies highlight the importance of rare, high-penetrance variants in familial aggregation of endometriosis, particularly the role of NPSR1 in severe disease. The successful integration of genetic data across species—from human families to rhesus macaques to mouse models—demonstrates the power of comparative approaches for validating and extending genetic discoveries [30].

Future research directions include comprehensive functional characterization of the identified genes and variants, particularly understanding how they interact with environmental factors and contribute to disease pathways. The exploration of multi-omics approaches—integrating genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data—holds promise for unraveling the complex pathophysiology of endometriosis [13]. Additionally, the translation of these genetic findings into clinical applications, including genetic risk prediction models and targeted therapies like NPSR1 inhibitors, offers hope for improved diagnosis and management of this debilitating condition. The continued investigation of these genomic landscapes will undoubtedly yield further insights into endometriosis biology and therapeutic opportunities.

Advanced Genomic Techniques and Analytical Frameworks for Rare Variant Identification

Family-based study designs represent a powerful methodological approach for elucidating the genetic architecture of complex disorders like endometriosis. By focusing on multi-generational families with multiple affected individuals, researchers can enhance statistical power to detect rare variants with potentially significant effects that might be obscured in large population-based studies. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, practical implementation, and analytical frameworks for leveraging familial aggregation in endometriosis research, with particular emphasis on identifying rare variants contributing to disease etiology. We present detailed experimental protocols, data analysis pipelines, and visualization tools to support researchers in designing robust familial genetic studies.

Endometriosis is a common, inflammatory gynecological condition affecting approximately 10-15% of women of reproductive age globally, characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity [18] [13]. The condition demonstrates significant familial aggregation, with first-degree relatives of affected women having a five- to seven-fold increased risk of developing the disease compared to the general population [18]. Familial cases often present with earlier onset and more severe symptoms than sporadic cases, suggesting a potentially stronger genetic component in these families [18].

While genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified numerous common variants associated with endometriosis risk, these explain only a fraction of the disease's high heritability, estimated at approximately 50% [18] [13] [11]. This missing heritability has prompted increased interest in rare genetic variants with potentially larger effect sizes that may contribute to disease susceptibility, particularly in multi-case families [18] [22]. The polygenic model of endometriosis, where multiple genetic variants act synergistically to influence disease risk, is increasingly supported by evidence from familial studies [18] [22].

Theoretical Foundations: Statistical Power in Family-Based Designs

Family-based studies offer several key advantages for rare variant discovery in complex diseases:

Genetic Homogeneity and Reduced Locus Heterogeneity

In multi-generational families, affected individuals likely share genetic risk factors inherited from a common ancestor. This genetic homogeneity increases the probability that rare pathogenic variants will be enriched in affected family members compared to unrelated controls. The shared genomic background within families reduces the confounding effects of locus heterogeneity—where different genetic variants can cause the same disease in different individuals—which often plagues case-control studies [18].

Enhanced Variant Filtering Through Co-segregation Analysis

The transmission pattern of genetic variants through a pedigree allows for powerful co-segregation analysis. Variants that perfectly or partially co-segregate with disease status across generations are strong candidates for functional involvement. This biological filtering approach significantly reduces the multiple testing burden compared to agnostic genome-wide searches [18].

Detection of De Novo and Private Variants

Multi-generational families enable identification of de novo mutations (newly arising in affected individuals) and private variants (unique to a specific family) that may contribute to disease risk. These variants are often rare in the general population but enriched in familial cases [18].

Table 1: Comparative Power Analysis of Study Designs for Rare Variant Discovery

| Design Feature | Population-Based GWAS | Multi-Generational Family Design |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Frequency Spectrum | Common variants (MAF >5%) | Rare to low-frequency variants (MAF <1%) |

| Effect Size Detection | Small to moderate (OR: 1.1-1.5) | Moderate to large (OR: 2.0+) |

| Sample Size Requirements | Large (thousands to tens of thousands) | Small to moderate (single large families to hundreds) |

| Control for Population Stratification | Requires careful matching | Built-in controls through relatedness |

| Ability to Detect Gene-Gene Interactions | Limited | Enhanced through pedigree structure |

| Variant Filtering Approach | Statistical significance | Biological (co-segregation) + statistical |

Methodological Framework: Experimental Design and Protocols

Family Ascertainment and Phenotyping

The foundational step in familial studies involves identifying suitable families with multiple affected individuals across generations. Ideal pedigrees demonstrate clear Mendelian inheritance patterns (autosomal dominant with reduced penetrance or polygenic) and clinical homogeneity.

Inclusion Criteria:

- Minimum of three affected individuals across at least two generations

- Surgical confirmation of endometriosis (rAFS stage III/IV preferred for severity)

- Detailed clinical documentation including symptom onset, lesion location, and associated comorbidities

Phenotyping Protocol:

- Standardized collection of surgical and histopathological reports

- Structured interviews for reproductive history, symptom characteristics, and treatment response

- Biobanking of DNA from peripheral blood and, when possible, endometriotic lesions

A recent study exemplifying this approach analyzed a multigenerational family comprising three sisters, their mother, grandmother, and a daughter, all diagnosed with endometriosis [18] [22]. This pedigree structure enabled researchers to trace inheritance patterns across four generations.

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) Technical Protocol

Whole exome sequencing provides comprehensive coverage of protein-coding regions, where the majority of disease-causing variants are predicted to reside.

Laboratory Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: High-quality genomic DNA isolation from peripheral blood leukocytes using standardized kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit)

- Library Preparation: Illumina TruSeq Exome Library Prep Kit with 75-100ng input DNA

- Exome Capture: Hybridization-based enrichment using Illumina Exome Panel

- Sequencing: Illumina platform with 100-150bp paired-end reads at minimum 100x mean coverage

- Quality Control: >90% of bases exceeding Q30 quality score, >80% coverage uniformity [18]

Table 2: Whole Exome Sequencing Quality Metrics and Performance Standards

| Quality Parameter | Minimum Threshold | Optimal Performance | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Coverage Depth | 80x | 100x+ | Samtools depth |

| Target Base Coverage | >90% at 20x | >95% at 20x | Picard CalculateHsMetrics |

| Duplication Rate | <10% | <5% | Picard MarkDuplicates |

| Mapping Rate | >95% | >98% | BWA MEM alignment |

| Transition/Transversion Ratio | 2.0-2.1 (whole exome) | 2.8-3.0 (coding) | GATV VariantEval |

| Q30 Score | >85% | >90% | FastQC |

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of sequencing data follows a structured workflow to identify high-probability candidate variants:

Bioinformatic Analysis Workflow for Familial Variant Discovery

Implementation Details:

- Alignment: BWA-MEM alignment to GRCh37/hg19 reference genome [18]

- Variant Calling: FreeBayes (v1.3.7) for SNP and indel discovery [18]

- Variant Filtering: Quality filters (depth >10, genotype quality >20), frequency filters (MAF <0.1% in gnomAD), and functional impact (missense, frameshift, stop-gain)

- Variant Annotation: enGenome-Evai and Varelect software for pathogenicity prediction [18]

- Co-segregation Analysis: Identification of variants shared by all affected family members

In the recent familial endometriosis study, this pipeline reduced approximately 20,000-25,000 raw variants per individual to 36 high-probability co-segregating rare variants through sequential filtering [18].